THE YEARLY READER

1900: On the Brink of Adulthood

The monopolistic National League lumbers into the 20th Century by continuing its self-served sleepwalk, a year before the American League is forced to wake it up.

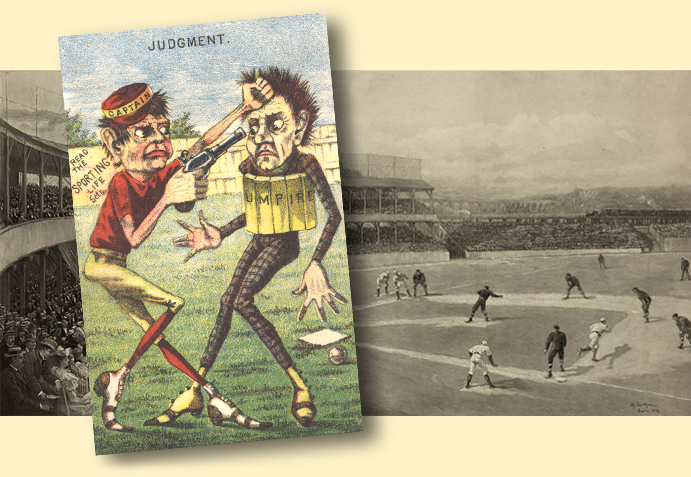

The lawless environment of 19th Century baseball is illustrated to (slightly) exaggerated effect in this Sporting Life commentary at left. The turn of the century provided little hope of improvement as a monopolistic and near-corrupt National League blindly trudged on. (The Rucker Archive [inset], Library of Congress)

The game of baseball entered the 20th Century as something of a juvenile delinquent. Throughout the 1890s, nobody behaved. Not the players, not the fans, not even the owners. Shoddy ballparks frequently burned down. Testosterone was spent in bulk, and the faint-of-heart need not apply. To attend the National Pastime was to engage in an occupational hazard.

As the calendar turned to 1900, there was hope that the game might soon grow up, get its life in order and settle into a more mature existence. Such prayers would soon be heeded. Until then, an indifferent baseball campaign would be played out in 1900 that resembled a hangover from the wild and woolly 1890s.

The 19th Century history of baseball reads like the first 20 years of a young person’s life, growing up, evolving, learning, misbehaving. Though the game exploded on a recreational level in the decades before the Civil War, the birth of the sport remains virtually untraceable. Baseball was not created in a single day by a single person. It certainly wasn’t whipped up by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, the stock theory given in the early 1900s. Nor was it imagined out of the blue by folks like Alexander Cartwright or Harry Chadwick, disparate people who helped elevate the game to an organized plain. It’s more likely that, instead, baseball took the Darwinist route of evolving from various other games such as rounders or cricket.

BTW: Abner Doubleday was given credit for inventing baseball until it was established that not only was he not in Cooperstown in 1839, but not once was baseball mentioned amongst his numerous memoirs

Its rampant growth tempered by the Civil War, baseball regained its momentum afterward and turned professional in 1871 with the advent of its first major league, the National Association. Over the next 20 years, baseball’s childhood would be an era of doing its homework but failing the exam. During this period, a total of five major leagues and 100 separate franchises—in towns as obscure as Keokuk, Elizabeth, Middletown and Troy—gave it a shot. By 1892, only one band would be left playing: The National League. Born in 1876, the league that would be nicknamed the senior circuit prevailed thanks to the reserve clause—which brought financial stability at the expense of the players, who were enslaved into perpetual servitude within the clubs that owned their rights.

The 20th Century Would not be Theirs

The National League would become the only one of five major leagues to survive the 19th Century, outlasting four others (listed below) that existed before or during its early reign.

Just as volatile as the ever-shifting major league landscape were the game’s pivotal rule changes, made as often as the changing of the seasons. In 1880, it took eight balls to be granted a walk; it would be whittled down to the current four by 1889. For a brief time in the late 1880s, it was four strikes and you’re out. By 1887, batters could no longer request a pitcher to throw high or low and, until 1891, players removed from a game were eligible to re-enter it. Most crucially, the distance between home plate and the pitching mound—moved from 45 feet to 50 in 1881—was shoved further back to the current 60 feet, six inches in 1893.

Baseball would assume a rebellious youth in the 1890s after the American Association’s death secured monopoly status for the NL. The decade would be among baseball’s most stagnant and uncivil, best reflected by the era’s most memorable team: The Baltimore Orioles, a group of brawling pranksters who won at all costs, and were led by third baseman John McGraw—a feisty, 5’7” troublemaker whose facial character had “beat it” viciously written all over it. The fans in the stands rooted by example, frequently engaging in an untamed form of audience participation. It got so bad that some ballparks put up barbed wire to separate the hoodlums in the bleachers from those on the field.

BTW: The Orioles’ intimidation tactics helped lead them to three straight NL pennants, from 1894-96.

The National League’s owners were no less behaved. Not only had they choked player payrolls with the reserve clause, but they had also set a salary cap of $2,400 per player that lasted through the balance of the 1890s—exceeded only on rare occasion for star players who used what little leverage they had to scratch and claw for the extra money. Further meddling with the league’s competitive element, a number of owners held control over multiple franchises, raising the potential of one team having its talent pool drained and emptied into that of another owned by the same magnate.

The downside to “syndicate baseball” was exposed with major embarrassment in 1899. The Cleveland Spiders were heavily plundered and sent to the St. Louis Perfectos by the Robison brothers—who owned both teams—and what was left of the Spiders was so awful, their fans literally stopped coming out to root for them. And when they stopped coming out—the Spiders drew just 6,088 spectators over 31 home games—the Robisons simply had the Spiders play their second half schedule almost entirely on the road. Cleveland lost 39 of its last 40 games, was outscored in its last nine (all losses), 111-22, and finished the year with a 20-134 mark that would make the 1962 New York Mets look respectable by comparison.

BTW: Some of the former Cleveland Spiders who escaped to St. Louis: Cy Young, Jesse Burkett, Mike Donlin and Lave Cross.

Mercifully, the Spiders would be taken off life support prior to the 1900 season. But three other teams—Louisville, Washington and even the Orioles—some of which had also suffered as the lesser halves of dual-ownership, would also get termination notices. Franchises were not all that got axed; NL owners also decided to reduce the number of umpires per game—from two down to one.

This NL’s last-minute contraction for 1900 left eight franchises that would stick around for a long, long time: Charter members in the Boston Beaneaters (Braves) and Chicago Orphans (Cubs); the Philadelphia Phillies and New York Giants, who joined the fold in 1883; and the St. Louis Cardinals (renamed from the Perfectos for 1900), Brooklyn Superbas (Dodgers), Cincinnati Reds and Pittsburgh Pirates—all of whom eventually jumped to the NL after starting out in the American Association.

Baseball’s last unilateral regular season was a tight but ultimately uninspiring campaign in which the eight NL survivors produced a 23-game span from first place to last.

The Philadelphia Phillies stormed into first place with a 22-10 start, but it was at that moment that the Phillies’ two young star hitters, Nap Lajoie and Elmer Flick, decided to pick a fine time to brawl. Their May 31 scuffle sidelined not only Lajoie for a month, but also the Phillies’ chances; the team played subpar baseball in Lajoie’s absence and never recovered.

BTW: Time has obscured the reasons behind the Lajoie-Flick fight; The Sporting News claimed it was over “such a trifling thing as a bat.”

That left the race for the NL pennant between Brooklyn and Pittsburgh, two teams who greatly benefited from franchise cutbacks elsewhere.

The Pirates, who hadn’t made much of a dent in a pennant race since 1893, had their talent pool sweetened with the arrival of several key Louisville refugees; the prime inheritance among them was, undoubtedly, 26-year old Honus Wagner. Discovered in 1896 by Ed Barrow—whose claim to fame as architect of the New York Yankees’ early glory years lay ahead of him—the muscular, gangly Wagner, now in his fourth major league season with the Pirates, initiated a dominant decade in which he would win seven NL batting titles with perhaps his very best performance—setting career highs in hitting (.381), doubles (45) and triples (22).

While the Pirates were able to absorb a fair team in Louisville, the Brooklyn Superbas were able to take in a very good one in the Baltimore Orioles. Already sound a year earlier with the transfers of acclaimed Orioles manager Ned Hanlon and miniscule (5’4”, 140 pounds) Willie Keeler—who continued to make good on his legendary motto to “hit ’em where they ain’t” by stroking out 200 hits every year since 1894—the Superbas became truly superb in 1900. Ex-Orioles were added in talented 21-year-old outfielder Jimmy Sheckard, veteran infielder Hughie Jennings, and pitcher Joe McGinnity—a workhorse of a pitcher who, a year after winning 28 games as a 28-year-old rookie for Baltimore, would win 28 more as a 29-year-old sophomore for Brooklyn.

Hanlon forged the same kind of results out of the Superbas as he often had with the Orioles: Aggressive hitting, relentless baserunning and a first-place finish. The Pirates gave chase late in the summer and pulled to within a game and a half of Brooklyn, but the overall balance of talent within the Superbas—part nee Orioles—would be too much to overcome.

One doleful bit of reality with the National League’s monopoly status was the absence of a meaningful postseason. When Brooklyn clinched first place, the season was basically done. Everyone played out the string. Oh, they did try a best-of-five “championship” series of sorts between the first-place Superbas and the second-place Pirates, but they had tried that as well with something called the Temple Cup in the 1890s. Few cared then, and few cared now; after all, why get excited over whether Brooklyn could outlast Pittsburgh in five games when they had already done it in 136? When the Superbas reproved their supremacy over the Pirates, three games to one, attendance in Pittsburgh—where all the games were played—was well below regular season average.

BTW: The series was sponsored by one of the local Pittsburgh newspapers; a silver cup went to the winning Brooklyn side.

The 1900 season had the look of stale leftovers. Reduced to eight teams, the National League could not prove that less was more. Per-game attendance remained steady from 1899 figures, but that was a disappointment given that it hadn’t spiked with the absence of the four weak links disposed of before Opening Day. Bad behavior continued to linger, both in the stands and on the field. The players, fed up with being trapped under the NL’s salary cap structure, formed a union in mid-1900 under the guidance of Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor. It took six months for the Players Protection Association, as the union was called, to get an appointment with the owners; when they finally got through the door, every suggestion they offered was promptly shot down. And then, days later—as if to punish the players for their dare to reform—the owners reduced team rosters to 16 players, in effect laying off ten per cent of the major league workforce.

It was hard to figure out if the owners were arrogant or stupid. Or both. As they shrugged their shoulders and laughed at a frustrated and angry union, their monopoly-fed addiction to leverage was soon to be rendered impotent with quick and cold reality. For the juvenile delinquent known as the National League was about to be shaken down and forced to grow up by a newly-arrived stepbrother whose house was well in order: The American League.

Forward to 1901: The American League Championed as a safe and honest alternative to the National League, the American League opens up for business.

Forward to 1901: The American League Championed as a safe and honest alternative to the National League, the American League opens up for business.

1900 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in the National League for the 1900 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1900 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in the National League for the 1900 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.