THE YEARLY READER

1908: The Merkle Boner

Nineteen-year-old rookie Fred Merkle costs the New York Giants a National League pennant by committing one of the game’s most notorious blunders.

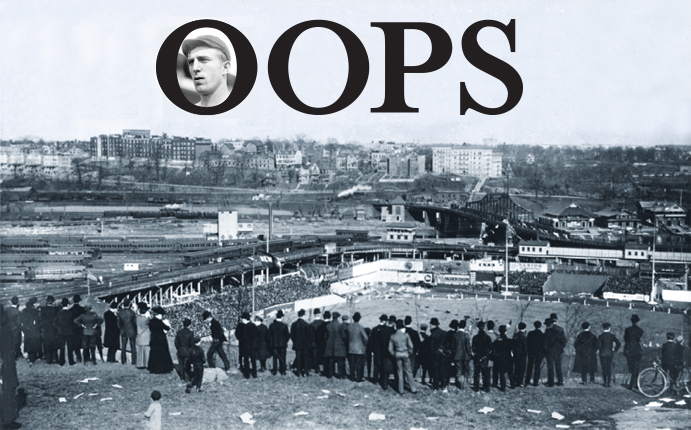

Any spot with a view of New York’s Polo Grounds is taken up on October 8 for a winner-take-pennant battle between the Giants and Chicago Cubs—made possible by the premature celebration of 19-year-old Fred Merkle (inset) on the basepaths a few weeks earlier. (The Rucker Archive, Library of Congress—CHS)

On September 4, 1908, Chief Wilson of the Pittsburgh Pirates lined a base hit against the Chicago Cubs that sent home the winning run in the bottom of the ninth. Warren Gill, the runner at first, started for second on the hit, watched the winning run score, then retreated to the clubhouse without reaching the base.

Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers, a glutton for the rulebook, quickly yelled for the ball from the outfield, got it, and stepped on second base—which, by the rules, would have forced Gill out and nullified the winning run.

The problem was, when Evers looked for umpire Hank O’Day to make the call, he had discovered that O’Day, too, had trotted off the field.

While little noise was made on the field, plenty was made off it afterward. The Chicago press demanded a replay, while Cubs owner Charles Murphy filed a protest with the National League. Murphy was rebuffed, while the press and fans alike outside of Chicago scoffed at the defending world champions for attempting to whine their way to victory.

The incident, however, did serve notice to umpires and players to be more alert next time.

Apparently, the New York Giants didn’t get the memo.

John McGraw, three years after winning his first World Series, had seen his Giants slip gradually to a .500 team by the end of 1907. Impatient with such results, he all but cleaned house for 1908. He released three of his aging field players (Dan McGann, Bill Dahlen and George Browne) and brought in younger, fresher talent to replace them on the roster. More importantly, he brought back into the fold Turkey Mike Donlin, who sat out all of 1907. Donlin, who spent the time off resurrecting his acting career, responded with a set of offensive numbers second only to the incomparable Honus Wagner.

The Pirates were also experiencing a revival, one shouldered almost single-handily by Wagner, but also helped by an improved pitching rotation led by 23-game winners in veteran Vic Willis and rookie Nick Maddox.

All of this meant true competition for the first time in two years for the Cubs. Their pitching remained stellar, their defense the best in all of baseball, and even their hitting was showing relative pop. But they were in a dogfight with both the Giants and Pirates, trailing New York by a game and a half when it came time to visit the Polo Grounds in late September.

After splitting a doubleheader, the teams returned for a day game on September 23. Cub pitcher Jack Pfiester was matched with Christy Mathewson, who, if he wasn’t having the best year of his career, was certainly having his most productive. By year’s end, Mathewson would top the NL in all of the following: A whopping 37 wins in 56 appearances totaling 390 innings; 34 complete games, 11 of them shutouts; a 1.43 earned run average; 259 strikeouts; and even five saves.

Pfiester held his own against Mathewson and dueled with him to the bottom of the ninth, tied at 1-1. Then the Giants started to rally. Art Devlin singled with one out; after Moose McCormick grounded into a force, up came 19-year old Fred Merkle, who had seen mostly bench duty and was only playing because regular first baseman Fred Tenney was resting from back pains.

Merkle singled, sending McCormick to third representing the potential game-winning run. That brought up shortstop Al Bridwell—who himself singled, sending in McCormick to win the game. Merkle, watching McCormick cross home plate, turned and headed straight to the clubhouse to join in the celebration.

He never bothered to touch second base.

With the Giants in victorious retreat to the clubhouse and part of the crowd of 25,000 flooding onto the field, Johnny Evers was trying desperately to get the attention of center fielder Solly Hofman, who had fielded Bridwell’s single. Hofman heeded but overthrew Evers; the ball came towards Giant pitcher Joe McGinnity, who picked up on what the Cubs were trying to do. A wrestling match ensued between McGinnity, Evers and Cub shortstop Joe Tinker, and McGinnity was able to lob the ball into the stands. Cubs Harry Steinfeldt and Rube Kroh raced into the stands, and had to wrestle the ball away from a fan.

Meanwhile, the Giants in the dugout slowly caught onto the situation. In vain they scrambled to get Merkle back out to second base, but it was too late. Evers was standing on second, ball in hand.

BTW: Many believe that the ball Evers stood on top of second base with was not the one hit into the outfield by Bridwell.

Worse for the Giants, umpire Hank O’Day—who had left the field early in Pittsburgh—was hanging around this time and ruled Merkle out, canceling the run and the win. The Cubs and O’Day both bolted to the clubhouse to avoid being pummeled by the criss-crossing of suddenly irate Giant fans.

The immediate postscript to what would eventually be known as the Merkle Boner was deafening. The New York press screamed. Giant fans screamed. The Cubs were going beyond the spirit of the game, relying on trivial technicalities, they all complained. Christy Mathewson, in protest, vowed never to pitch in the majors again if the Giants were stripped of victory.

It would be an interesting day for National League president Harry Pulliam when asked to rule officially on the matter. He heard it from both sides. The Giants actually claimed Merkle had touched second base and the run was legit. The Cubs not only felt that the run was void, but that they should be awarded a forfeit because fans had run onto the field, making further play impossible.

BTW: Fred Merkle’s story: Mathewson took him by the arm and trotted out to second base where Robert Emslie, the game’s other umpire, reassured them that the run was valid.

Pulliam, who was at the game and had, first-hand, viewed the entire incident himself, sided not so much with either team but with the umpire, Hank O’Day—who stated that Merkle had not touched second and nullified the run. Furthermore, increasing darkness would have made continuing the game impossible. The game was ruled a 1-1 tie, to be made up—but only if the Giants and Cubs finished in a flat-footed tie for first place at season’s end.

Pulliam did give the Giants one edge; if there was to be a make-up, the Giants were given the option to either play a one-game playoff or a best-of-five series to decide the pennant. Nobody’s fool, John McGraw went for the one-shot option, knowing that he could use a dominant Christy Mathewson as his starting pitcher.

All of this would have been meaningless had it not been for the Cubs’ final regular season game, against the Pirates. By beating Chicago, Pittsburgh would have won the pennant outright regardless of what the Giants had left. As it was, the Cubs won a thrilling contest and awaited the outcome of a three-game series the Giants had yet to play in Boston; if the Giants swept, they would tie the Cubs in the standings and the Merkle Boner make-up would be on.

Sure enough, the Giants won all three at Boston.

Never before had two teams tied for first place in major league history, and now two bitterly contentious adversaries, the Cubs and Giants, were ready to square off in a winner-take-all scenario at the Polo Grounds.

Gotham was ready to give the Cubs all the hell it had.

The level of gamesmanship between the Giants and Cubs before the tie-breaking make-up contest was such that they even argued over where the overflow crowd should be placed. (Library of Congress)

When New Yorkers discovered where the Cubs were staying, they blared their horns and yelled well into the night in an attempt to keep the players awake. When game time approached the next day, a gathering estimated as high as a quarter of a million surrounded the Polo Grounds. Every speck of land and structure that had a vantage point of the field was consumed by humanity. Several people, both inside and outside the stadium, reportedly fell to their deaths while dangerously attempting to improvise new viewing areas. Cub players were needled, sometimes physically, by Giant fans and players who got too close. Under the stands, umpire Bill Klem was offered a $2,500 bribe from Giant team physician Joseph Creamer. (Klem declined and Creamer was eventually barred from the game for his doings.)

Once again, it was Pfiester vs. Mathewson on the mound, but this time neither was sharp. Pfiester hit the first batter and lacked any kind of control—but fortunately for the Cubs, they had a bullpen option in staff ace Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, who took over before the first inning was over with the Giants ahead, 1-0. In the third, the Cubs rallied off a shaky Mathewson to pull ahead, 4-1. Big Six recovered, but the Giants could only touch Brown for a run the rest of the way, losing 4-2.

NL champs for the third straight year, the Cubs had to endure one last challenge: Escaping New York alive. Running the gauntlet to the center field clubhouse, player-manager Frank Chance suffered a severe cut from a broken bottle thrown at him; Pfiester was slashed in the shoulder by a knife. The Cubs left the Polo Grounds in two paddy wagons, and departed their hotel in the dead of night via the back entrance.

The pennant race in the American League was far less hostile but just as exciting. In the season’s final week, three teams were solidly in contention: The Chicago White Sox, the Cleveland Naps, and the reigning league champion Detroit Tigers.

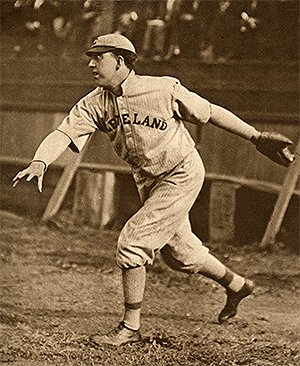

With the American League pennant on the line, Cleveland’s Addie Joss pitched the second perfect game in AL history, outdueling Ed Walsh and the Chicago White Sox on October 2. (The Rucker Archive)

Walsh did win game number 40 in his last start—against Detroit, bringing the Sox within a half-game of both the Tigers and Cleveland going into the last day of the season. But the Tigers broke free and repeated as AL champs by defeating Chicago, 7-0, while the idle Naps could only wait after blowing a chance to clinch the day before against St. Louis, losing to the Browns. Detroit finished a half game in front, in part due to a rainout that was never made up.

BTW: If forced to have played the make-up game—as major league rules now require—the Tigers would have paired up against lowly Washington, who they beat 16 out of 21 times. The likely starter for the Senators, however: Walter Johnson.

Frequent and First-Rate

In the heat of the AL pennant race, the White Sox sent workhorse ace Ed Walsh to the mound 11 times over a 25-day period—and he responded with a phenomenal string of performances. The White Sox generated only 19 total runs over Walsh’s 11 starts, but he still won eight of them; the team failed to score in all three of his losses.

The Tigers were led once again by Ty Cobb, who led a more peaceful existence with his teammates—though he continued to punish opponents with a .324 batting average, 188 hits including 36 doubles and 20 triples, and 108 RBIs, all AL highs.

The World Series became a one-sided exercise in anti-climaticism, given the heated and controversial pennant races that preceded it. In a rematch of the 1907 Fall Classic, Detroit again provided little competition for the Cubs. They did manage to avoid a sweep for the second straight year by winning Game Three at Chicago, 8-3, but that only seemed to strengthen Chicago’s resolve; Three Finger Brown and Orvie Overall fired shutouts in Games Four and Five to help the Cubs win their second straight world championship.

It would be over a century before they’d win it all again.

Forward to 1909: Three-Beat Sudden ace Babe Adams of the Pittsburgh Pirates stifles the Detroit Tigers into their third straight World Series loss.

Forward to 1909: Three-Beat Sudden ace Babe Adams of the Pittsburgh Pirates stifles the Detroit Tigers into their third straight World Series loss.

Back to 1907: The Cultivation of a Georgia Peach Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers with their first pennant.

Back to 1907: The Cultivation of a Georgia Peach Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers with their first pennant.

1908 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1908 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1908 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1908 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.