THE YEARLY READER

1930: The Big Blastcast of 1930

Baseball’s offensive frenzy begun in the 1920s skyrockets to record heights with eye-popping numbers, leaving pitchers shellshocked and begging for relief—not from the bullpen, but from the owners.

(Library of Congress)

Guy Bush had the kind of year that might have chased other major league pitchers into immediate retirement.

In 225 innings, the Chicago Cubs right-hander gave up an all-time National League record 155 runs, on 291 hits and 86 walks. He allowed 22 home runs. Opponents batted .316 against him. His earned run average was a bruising 6.20.

His record: Fifteen wins, 10 losses.

You read right. Fifteen and 10.

Such was life in baseball in 1930.

For 10 years, the hitter had held sway in the war between batter and pitcher. The spitball had become illegal. Balls were replaced more frequently during the game to routinely give batters something new, bright and bouncy to pound away at. And the influence of Babe Ruth tempted others to realize that the home run could be a strategically powerful new dimension to the game. It all added up to a demonstration of offense during the 1920s that was unparalleled in baseball history.

But for outrageous exhibitions in hitting, the 1930 season put everything before it to shame.

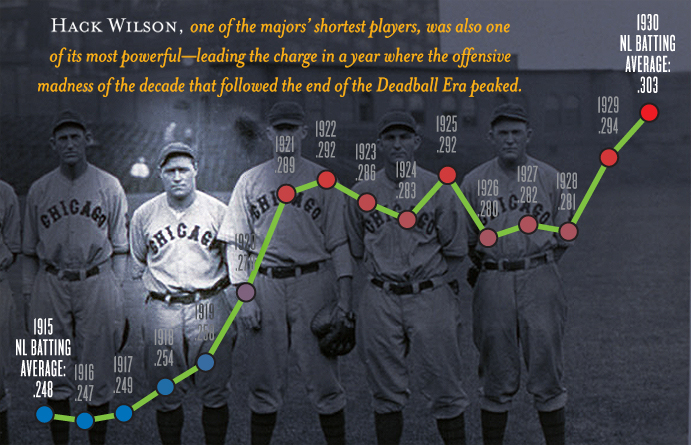

Nine of the 16 major league teams batted over .300. The NL as a whole hit .303. Never before or since has any league shown such exploitation in hitting.

Both leagues set new highs in home runs and runs scored. The New York Yankees became the first team in history to score over 1,000 runs—an average of nearly seven per game. On the road, they racked up 591—translating to almost eight runs a game away from Yankee Stadium.

Pitchers became so shellshocked from the return fire, they began to wonder if they were trapped within a hopeless shooting war. Guy Bush’s “winning” season was hardly the league’s only statistical abnormality. There was Ray Kremer of the Pittsburgh Pirates, a 20-game winner in 1930—with an ERA of 5.02.

The guys on the other end—those with the bats—were enjoying the year as much as the pitchers were dreading it. Bush’s teammate in Chicago, Hack Wilson, had the kind of year that might have made even Babe Ruth envious; he shattered a NL record with 56 home runs, and a major league mark with an incredible 191 runs batted in. The latter mark has been approached, but never broken.

Over in New York, the Giants’ Bill Terry became the last NL player to date to hit over .400. The Giants as a team hit .319, the highest ever recorded by any one team in modern history.

BTW: Terry’s 254 hits tied the NL mark set just a year earlier by Lefty O’Doul; the record has yet to be broken.

Then there were the Philadelphia Phillies.

Chuck Klein’s phenomenal season at the plate couldn’t hide the failures of his pitching teammates on the Phillies, who collectively gave up an opposing batting average of .346 on their way to 102 losses. (Chicago Historical Society)

The no-sot-fabulous Baker Bowl boys were the poster children for the NL’s offensive insanity. The Phillies batted .315—second to the Giants, and the third highest since 1900—and were led by outfielder Chuck Klein, who produced numbers others might be too embarrassed to dream of: A .386 average, 250 hits (including 59 doubles and 40 home runs), 170 runs knocked in and 158 scored. Klein’s teammate Lefty O’Doul was close behind with a .383 average. Third baseman Pinky Whitney hit .342. Most everyone else hit over, if not close to, .300.

All this, and the Phillies lost 102 games.

The team’s pitching—or its lack thereof—grouped together to rewrite the record books in the worst way. The Philadelphia team ERA of 6.71 remains the highest in modern major league history to this day, and opposing teams hit .346 against the Phillies—another unbroken, dubious feat. Les Sweetland started 25 games for the Phillies, winning seven, losing 15, and posting a horrific 7.71 ERA. Les had company. Fellow starter Claude Willoughby had a 7.59 ERA and lost 17 of 21 decisions. Hal Elliot led the NL in appearances and wished he hadn’t; his ERA checked in at 7.69.

Not even the great Pete Alexander, coming back home to where he began his stellar major league career 19 years earlier, could save the Phillies. Neither home nor he was the same. The 43-year old appeared nine times for Philadelphia—not winning once while losing thrice, registering a 9.00 ERA before fleeing to a safer place: Retirement.

BTW: If Alexander had snuck away with just one win, he’d be the all-time NL leader in wins today; his 373-372 edge over Christy Mathewson was erased in later years when historians gave Mathewson an extra win that he previously had not been given credit for.

Though the pitching was indeed bad, Baker Bowl’s small dimensions shared a bit of the blame as well. Left-handed hitters pulled and right-handed batters went the opposite way toward the frightfully close right-field fence, which measured 280 feet down the line and only 300 feet to right-center—before assuming more normal distances throughout the rest of the ballpark. True, the right-field wall was over 40 feet high, but all Phillies outfielders could do with any decently hit fly ball was to either play it off the wall or watch it go bye-bye. It’s the reason that the Phillies, year after year, had the league’s worst team ERA for 14 years running; but in 1930, the noise off that wall was especially deafening.

The Flip Side of 1930

While most everyone was hitting near, above or well above the .300 mark, there were a select unlucky few who managed to miss jumping on the bandwagon. Below are the five lowest qualifying batting averages during the 1930 season.

On the top side of the NL standings, the St. Louis Cardinals clinched their third pennant in five years with a late and furious entry into the pennant race. A .500 team as late as mid-August, the Cardinals flew into top gear and won 39 of their last 49 games, swooping past the early contenders: The Cubs, who despite those monstrous Hack Wilson numbers lost Rogers Hornsby to a broken ankle in May; and the Brooklyn Robins, who had the league’s best team ERA—at 4.03.

One last strange hurdle for the Cardinals to clear came during a crucial late-season series at Brooklyn. Pitcher Flint Rhem, winner of six straight games and slated to start the first contest against the Robins, disappeared and didn’t show up until two days later—battered and tattered, claiming he had been kidnapped and forced to consume large volumes of whiskey in an effort to keep him from playing. Few believed the story that Rhem, known for his heavy drinking, would actually be forced to drink. Nevertheless, the Cardinals went on without him and swept the Robins in three games.

Burleigh Grimes, the last legal spitballer, was one of the few pitchers to stand tall against the majors’ non-stop hitting assault in 1930—and, at age 36, helped push the Cardinals into the World Series. (The Rucker Archive)

The Cardinals’ pitching staff received a major boost from 36-year old veteran Burleigh Grimes. Starting the year like everyone else, Grimes accumulated a 7.35 ERA in 11 games before being traded from the Boston Braves. With the Cardinals, Grimes played like he was back in the deadball era; in a sense he was, for he was one of the few pitchers left who was still allowed to throw the spitball 10 years after its abolition. Grimes went 13-6 at St. Louis and registered a 3.05 ERA quite uncharacteristic for 1930.

The Philadelphia Athletics suffered no major offseason changes, no major midseason injuries and retained a roster of talent one year more mature, together and wiser than their breakthrough American League pennant of the year before.

Balance was the key to the A’s second straight AL flag. Second-place Washington, eight games back, had the better pitching, but lacked the muscle at the plate. The Yankees, another eight games back in third, had plenty of muscle—but suffered behind a pitching staff that was next-to-last in AL team ERA.

The A’s were once again led by the devastating one-two punch of Jimmie Foxx and Al Simmons, with Simmons leading the AL in hitting (.381) and runs scored (152). Meanwhile, Lefty Grove dominated AL pitching, leading the league with a 28-5 record, a 2.54 ERA (next best in the AL: Cleveland’s Wes Ferrell, at 3.31); next best in the AL: Cleveland’s Wes Ferrell, at 3.31. Grove became the first AL pitcher to strike out 200 batters since Walter Johnson in 1916, and even found the time to save a league-high nine games.

BTW: Batters hit just .247 against Grove, a superior figure by 1930 standards.

Alright, Empty Your Pockets…

Lefty Grove (AL) and Dazzy Vance (NL) both led their respective leagues in earned run average by margins so wide, they’re among the all-time top five from each league as shown below.

Pitching would ultimately get the last laugh during the World Series. As experts braced for an orgy of offense to mirror the regular season, two teams that hammered away all year at opponents could do little at the plate against one another. The Cardinals batted .200; the A’s, only .197.

But it was the Athletics who made their hits count. Eighteen of their 35 safeties were for extra bases, including six home runs—two each by Simmons and catcher Mickey Cochrane—to give the A’s their second straight world championship in six games.

After being placed in the shadows of Howard Ehmke’s spotlight the year before, Philadelphia pitchers Lefty Grove and George Earnshaw emerged as the workhorse stars of the Series. Having paired up for 50 wins during the season, the two pitched all but eight innings of the Series and figured in every decision, except a 5-0 loss suffered by Rube Walberg in Game Three. Grove and Earnshaw combined for a stellar 1.02, and allowed only 28 hits and 10 walks—striking out 29—in the 44 innings they pitched.

The lack of hitting in the Fall Classic gave promise to those who thoroughly tired of the wacky hitting spree before it. Though the increase in offense figured in record attendance across the majors—over 10 million fans crossed the turnstiles in the year following the Wall Street crash of 1929—baseball insiders worried that it was ruining the integrity of the game.

Changes were proposed. Giants manager John McGraw wanted the pitching mound moved two feet closer to home to give hurlers more advantage. Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, of all people, suggested lifting the ban on spitballs. Walter Johnson, retired and managing the Senators at age 42, thought seriously of stepping back out on the mound.

While the AL did nothing, the NL moved to bring in a new ball for the 1931 season that would have less pop. Whatever the cause—a deader ball, better pitching, or simply something different in the air—batting averages would plummet in 1931. The AL would drop 10 batting points, while the NL fell a whopping 26 points to a still-potent .277 average.

The 1930 campaign indeed became the booming crescendo that capped off one of baseball’s most thunderous eras of hitting. Normalcy was about to return, and from it would come an equally fine dose of hitters and pitchers.

And no more pitchers with a winning record and an ERA of 6.00.

Forward to 1931: The Peppering of Philly Aggressive and colorful, Pepper Martin leads the St. Louis Cardinals in ending the Philadelphia A’s two-year rule over baseball.

Forward to 1931: The Peppering of Philly Aggressive and colorful, Pepper Martin leads the St. Louis Cardinals in ending the Philadelphia A’s two-year rule over baseball.

Back to 1929: Running on Ehmke All but washed up, veteran pitcher Howard Ehmke gets the dream call for Game One of the World Series and delivers, setting the tone for a long-overdue championship for the Philadelphia A’s.

Back to 1929: Running on Ehmke All but washed up, veteran pitcher Howard Ehmke gets the dream call for Game One of the World Series and delivers, setting the tone for a long-overdue championship for the Philadelphia A’s.

1930 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1930 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1930 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1930 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.