THE YEARLY READER

1950: Gee Whiz!

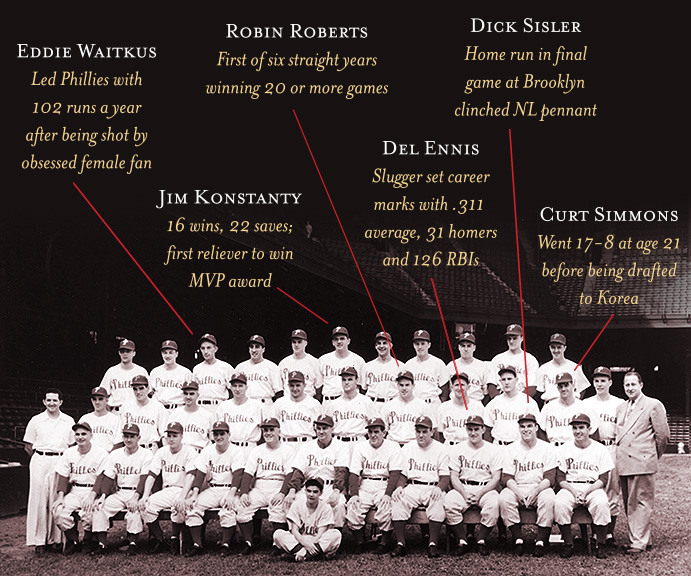

Though disappointed in the World Series, the Philadelphia Phillies become the darlings of baseball with a stunning NL pennant won on the last day.

(The Rucker Archive)

If the Philadelphia Phillies had any New Year’s resolutions to wish for with the ringing in of the 1950s, it would have likely been to make everyone forget about the 1940s.

It had been a largely disgraceful era for the Phillies, even when compared to their dark days at decrepit Baker Bowl in the preceding decades. The franchise teetered on the brink of bankruptcy in the early 1940s and struggled through a succession of short-term owners. After the front office stabilized with DuPont vice president Robert Carpenter’s purchase of the club in 1946, the Phillies wallowed through a public relations disaster in 1947 caused by manager Ben Chapman’s abhorrent racist taunting of Jackie Robinson. Above all of this, of course, was that the team still wasn’t winning.

Chapman was fired in 1948, immediately fixing one problem. Back in the Phillies’ executive offices, the issue of winning was on its way to being successfully addressed by the team’s general manager, former New York Yankees pitcher Herb Pennock, who had shrewdly pieced together a collection of young and talented players that would begin a gradual rise in the standings. By 1950, this collection—forever to be remembered as the Whiz Kids—was ready to make a definitive statement to the rest of baseball.

BTW: Pennock died in 1948 before he had the chance to see the fruits of his labor.

The Phillies of the new decade were the youngest in the National League, and their potential would resonate through the 1950s. Although such impact hardly translated into a dynasty, the Phillies’ sudden burst of success in 1950 would take everyone by surprise.

Among those representing the new way at Philadelphia would be a pair of young outfielders paving an early road to outstanding and consistent careers. Local product Del Ennis had developed as the prime power source in the Phillies’ lineup, and in 1950 he set career highs with 31 home runs and a league-leading 126 runs batted in. Richie Ashburn, meanwhile, hit .303 at age 23 and patrolled center field with authority, though overall he was just warming up his Hall-of-Fame credentials.

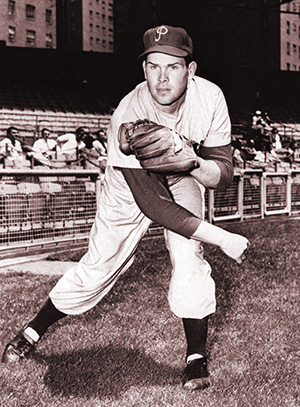

Another 23-year old on the verge of superstardom gave the Phillies a breakout performance on the mound. Right-hander Robin Roberts matured into the team workhorse with 20 wins and a 3.02 earned run average over 300 innings, only mildly setting his own standard for a string of monster campaigns that lay ahead of him.

BTW: Roberts became the Phillies’ first 20-game winner since Pete Alexander in 1917.

But the absolute true glue of the 1950 Phillies came not from the everyday lineup or the starting rotation but, instead, from the bullpen. Jim Konstanty, a bespectacled late bloomer at age 33 with a mild-mannered demeanor and a palmball that did wonders on its slow journey across the plate, was called upon to pitch in a then-record 74 games, all of them in relief. He made the most of his diligence, winning 16 games, saving 22 others (another NL record, for the moment) and posting a 2.66 ERA that would have led the NL had he pitched two more innings to meet the minimum eligibility requirements. Opposing batters, confounded, could only hit .205 against Konstanty, who became the first reliever to win a Most Valuable Player award.

The City of Brotherly Duds

The Phillies’ pennant-winning success in 1950 was, if anything else, long overdue satisfaction for Philadelphia baseball fans who spent the 1940s cowering their heads in disgrace over the complete incompetence of both the Phillies and A’s—the two major league teams which, by the record, were the worst of the decade.

The Whiz Kids stormed into first place and stayed there throughout the long, hot summer. By the middle of September, with a luxurious cushion at hand over second-place Brooklyn, the NL pennant appeared to be in the bag. But the invincibility quickly began to erode in the waning weeks with a serious run of bad luck. Pitcher Curt Simmons, a 21-year-old lefty who like Roberts exploded on the scene with a 17-8 record, became the first major leaguer called up by the military to serve in the Korean “Police Action.” Two other pitchers became injury list material as Bubba Church had his face smashed by a lined shot off the bat of the Reds’ Ted Kluszewski, and Bob Miller hurt himself apparently picking up a suitcase the wrong way. And catcher Andy Seminick, who would bat .288 with 24 home runs, played in severe pain the rest of the year after taking the brunt of a home plate collision with the New York Giants’ Monte Irvin.

Leading by 7.5 games with 11 left to play, the Phillies managed to nearly cough it up. They lost eight of those first 10, while the Dodgers—displaying an electrifying offense led by Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Roy Campanella and Jackie Robinson—fired themselves up and whittled the lead down to a single game, with one contest remaining in the season. That contest: The Phillies and Dodgers at Ebbets Field, a season settler that would be one of the most memorable in baseball history.

Robin Roberts was heavily relied on by the Phillies to win the pennant, starting three times in a five-day stretch to end the year—including a 10-inning masterpiece on the final game at Brooklyn to give the Phillies the NL flag. (The Rucker Archive)

The Dodgers looked primed to complete an amazing season comeback when, still tied at 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth, Duke Snider lashed a hit up the middle with men on first and second and no one out. Astonishingly, lead runner Cal Abrams was waived around third to challenge the throw from Richie Ashburn—who was playing shallow. Ashburn’s throw beat Abrams to home by a mile, and Roberts quickly snuffed out what little remained of the rally to force extra innings.

The Phillies immediately threatened in the 10th and, unlike the Dodgers, made good on it—as Dick Sisler launched a three-run blast off Newcombe. George Sisler may have been proud of his son but not entirely thrilled; he was seated behind the Brooklyn dugout, witnessing the event as a member of the Dodgers front office.

Roberts pitched a perfect 10th to finish off the Dodgers, and the Whiz Kids finally secured the Phillies’ first pennant in 35 years.

While an upstart took command of the NL, the usual suspects continued to keep the American League predictable enough.

A year after bringing the Yankees back to the game’s pinnacle, manager Casey Stengel still felt he hadn’t made enough believers. “You won once, Case,” he might have heard time and time again. “Now show us it wasn’t a fluke.”

Stengel’s challenge was to deliver back-to-back AL pennants to New York for the first time in seven years, and that mission would be made difficult with a number of rivals taking their best shots.

The biggest thorn in the Yankees’ side would be the Detroit Tigers, who held first place for much of the year under ex-Yankee Red Rolfe. In their quest to overtake the Tigers down the stretch, the Yankees embarked on a number of late-season acquisitions that would tip the balance of power their way. The most significant roster move came with the promotion of 21-year-old, happy-go-lucky southpaw Whitey Ford, who immediately displayed his confident knack for winning by taking his first nine decisions in the win column, before finally tagged with a loss pitching relief in the season’s final week.

Ford’s belated contribution aided a solid corps of starters who were each roughly a decade or more older, led by Vic Raschi’s 21 wins (against nine losses). Catching the rotation was Yogi Berra, who started all but seven games behind the dish—while flowering into a dangerous offensive threat at the plate, batting .322 with 28 home runs and 124 RBIs. Joe DiMaggio, now 35, joined Berra at the top of the statistical chart with his last great year: A .301 average, 32 homers, 122 RBIs and a league-leading .585 slugging percentage.

Place blinders around the Boston Red Sox’ list of offensive numbers, and one would have a hard time believing the team could only finish third. But they did, despite the fact they would be the last team to date to collectively hit .300, and the last until the 1999 Cleveland Indians to score over 1,000 runs. It could have been worse for opposing pitchers had Ted Williams not missed two months after colliding with the outfield wall at Chicago’s Comiskey Park during the All-Star Game.

BTW: Curiously, Boston went 44-17 with Williams on the shelf; with him, they managed to barely stay above .500.

Alas for the Fenway Faithful, the Red Sox couldn’t overcome a rough start in which Joe McCarthy—old, tired and losing respect from his players—walked away from the manager’s post. And the Sox certainly weren’t helped by a pitching staff that tanked with a 4.88 team ERA, third worst in the AL.

Red Socking

No team in baseball’s postwar era has hit as high or scored as many runs as the 1950 Red Sox. Anchored by Ted Williams—the last player to hit .400—the Sox remain the last team to hit .300.

With Robin Roberts exhausted from his extensive duty of the season’s final week, and most every other starter hurt or unavailable, the Phillies announced the most off-the-wall starting assignment for a World Series opener since the Philadelphia A’s placed Howard Ehmke on the mound in 1929. Jim Konstanty hadn’t started a game in six years, yet Phillies manager Eddie Sawyer went with his gut and believed Konstanty was his best bet. Konstanty’s Game One performance at Shibe Park would be a hollow vindication for Sawyer; he lasted eight innings and allowed only one run on a sacrifice fly, but he was outdueled by Yankees starter Vic Raschi—who tossed a two-hit shutout.

BTW: Curt Simmons, drafted away by the military, was furloughed during the World Series and available to pitch—but he was denied by the commissioner’s office.

For the Whiz Kids, the first game set the tone for a truly frustrating World Series experience. Allie Reynolds and a refueled Robin Roberts squared off into extra innings for Game Two, but the Yankees again gained the edge when Joe DiMaggio’s massive home run won it in the 10th. In Game Three at New York, The Phillies led 2-1 behind a strong effort from starter Ken Heintzelman, who had struggled through the regular season; but after retiring the first two batters in the eighth, Heintzelman walked the bases loaded, and an infield error brought home the tying run. With Russ Meyer pitching in the ninth, the Yankees made it three tight triumphs in a row as Gene Woodling scored the go-ahead run on a Jerry Coleman single.

BTW: After winning a career-high 17 games in 1949, Heintzelman limped to a 3-9 mark in 1950.

Whitey Ford secured the sweep in Game Four as the Yankees finally coasted, their 5-2 triumph retaining their standing as world champions.

It was a disappointing end to a roller coaster ride for the Phillies, but as the bloom was blown off the Whiz Kids in October defeat, their consolation lay in the establishment of a consistently higher level of play that made the memories of those long years of decades past thankfully more distant.

Forward to 1951: The Shot Heard ‘Round the World Bobby Thomson’s historic home run caps one of baseball’s greatest pennant races for the New York Giants.

Forward to 1951: The Shot Heard ‘Round the World Bobby Thomson’s historic home run caps one of baseball’s greatest pennant races for the New York Giants.

Back to 1949: Casey at the Helm The zany Casey Stengel silences the critics and embarks the New York Yankees on a long and fruitful dynasty.

Back to 1949: Casey at the Helm The zany Casey Stengel silences the critics and embarks the New York Yankees on a long and fruitful dynasty.

1950 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1950 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1950 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1950 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Bill Wight, who played for eight different teams—six in the American League alone—discusses the colorful personalities and the baseball way of life during the postwar era.

Bill Wight, who played for eight different teams—six in the American League alone—discusses the colorful personalities and the baseball way of life during the postwar era.