THE YEARLY READER

1960: A-Maz-ing!

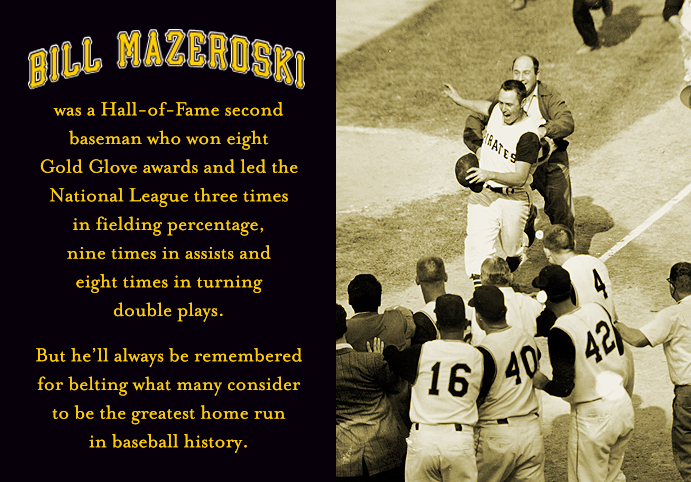

Despite being heavily outscored in the World Series, the Pittsburgh Pirates somehow make the most of it and defeat the New York Yankees—dramatically accenting the achievement with Bill Mazeroski’s legendary home run.

(Associated Press)

Back in 1927, when the mighty New York Yankees swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series, they outhit them by 56 batting points, outscored them 23-10, and hit the Series’ only two home runs.

Thirty-three years later, when the two teams met again in the Fall Classic, the Yankees outhit the Bucs by 82 batting points, outscored them 55-27, and out-homered them 10-4.

Sweep repeated?

No. The Yankees lost in seven games.

It all looked great on paper for the Bronx Bombers in the 1960 World Series until the box scores were broken down game by game. While the Yankees fattened the stats by packing a destructive punch in three big blowouts, it was the Pirates who mastered the close games and tipped the balance in their favor with the most important statistic of all: Wins. And they would do it with legendary panache, climaxing one of the most bizarre and talked-about World Series ever played thanks to a quiet, amiable player whose defensive skills at second base were so brilliant, it’s almost a shame he would be best remembered for hitting one of the greatest home runs in the game’s history.

When Bill Mazeroski signed on with the Pirates straight out of high school in 1954, he was considered just another cheap prospect in Branch Rickey’s latest attempt to turn a laughingstock organization into a powerhouse. Mazeroski wasn’t alone; Rickey was quietly harvesting a bumper crop of young players with the same philosophy he used 30 years earlier in St. Louis: Collect enough rocks and a few gems will emerge. Mazeroski was just one of hundreds who had a chance, nothing more.

Many questioned whether Rickey, exiled from Brooklyn, had any talent-building magic left. He had remarkable success remaking both the Cardinals and Dodgers—the former through the innovation of the farm system, the latter through the innovation of racial integration. But once at Pittsburgh, Rickey had no new angle to exploit—only his reputation for superior scouting.

Rickey spent five years attempting to rebuild the Pirates, and by the time he left in 1955, it appeared he’d met with major failure. The team had finished last during four of those years, next-to-last in the other, and averaged over 100 losses a year. Along with Mazeroski, Rickey’s discoveries during his tenure—including shortstop Dick Groat, first baseman Dick Stuart, outfielder Bill Virdon and pitchers Bob Friend, Vern Law and Roy Face—initially gave Pirates fans little hope that the future would be any brighter. Even the one blue-chip prospect Rickey had uncovered, a gifted Puerto Rican kid named Roberto Clemente, seemed too young and unrefined to make any immediate impact in Pittsburgh.

The Bucs Flopped Here

The Pirates came around as a viable challenger at the end of the 1950s, but it wasn’t enough to avoid being labeled as the worst team, by the record, for the decade.

Once more, however, Rickey would get the last laugh, albeit in absentia. As Rickey would be responsible for supplying the genie in the bottle, it was manager Danny Murtaugh who got credit for finally letting it out.

Murtaugh took over for a beleaguered Bobby Bragan in 1957 and, almost as easily as flipping a switch, got the Pirates to power on. Under his reign, Murtaugh got the Bucs to close out 1957 by playing .500 ball—stop-the-press news given the Pirates’ cellar dwelling of the past decade—and uplifted them further to a second-place finish in 1958. They finished fourth in 1959 but were no less competitive, full of eye-opening personal achievements such as reliever Roy Face’s 18-1 record and starter Harvey Haddix’s famous 12-inning perfect game, which he lost in the 13th.

The 1959 trade for Haddix, along with third baseman Dick Hoak and catcher Smoky Burgess from Cincinnati for star slugger Frank Thomas and three lesser players, was considered the final piece of the promising championship puzzle at Pittsburgh. With a year under their belts together, the new and complete mix of Pirates entered 1960 thoroughly confident that they could seize the National League pennant. They weren’t about to disappoint their fans in realizing that assessment.

Solid and well-balanced in just about every facet of their game, the Pirates successfully glided through 1960, never slumping, never collapsing. They led the league in batting, earned run average, and fielding. Their clutch game resulted in 23 victories in their last at-bat. Vern Law earned the Cy Young Award with a career-high 20 wins against nine losses. Roberto Clemente, who for five years had shown only scant signs of potential greatness, finally came into his own with a .316 average, 16 home runs and 94 runs batted in. Starting pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell and reliever Clem Labine made significant contributions after joining the team via midseason trades. Even the bench came alive; when Dick Groat went down with a broken wrist in the season’s final month, Dick Schofield filled in and batted at a near-.400 clip.

BTW: Mizell was 13-5 in 23 starts for the Bucs; Labine won three, saved three, and produced a 1.50 ERA…Groat, who won the NL batting title at .325, would also win the league’s Most Valuable Player award.

Though Bill Mazeroski was showing his usual brilliance at second base—teammates called him “No Hands” because his movements in turning a double play were so quick—his batting numbers were not cooperating. Stuck well below the .250 mark at mid-summer, Mazeroski received adjustment tips from batting coach (and Hall of Famer) George Sisler, who told him to be more patient at the plate. The advice worked, and Mazeroski headed into the postseason hitting .328 over the regular season’s final two months.

For their first return to the World Series in 33 years, the Pirates would meet up with their 1927 rivals: The New York Yankees.

After stumbling the year before, the Yankees were back—but it took them a while to rev up. Another lackluster start and a two-week absence by 70-year-old manager Casey Stengel (resting after a case of chest pains) suggested to many that the cracks in the Yankee mystique were deepening. Even Mickey Mantle was thrown into the fans’ doghouse after he failed to run out a double play while teammate Roger Maris hurt himself at second base trying to break it up.

BTW: Mantle, who thought there were two outs when he hit into the double play, atoned by cracking two of his AL-leading 40 home runs the next day.

The Yankees tolerated manager Casey Stengel’s Vaudevillian personality so long as he won championships; but as he turned 70 and went successive seasons without a World Series title, he was let go. (The Rucker Archive)

The Yankees eventually righted themselves and overcame the contenders of the day: Defending AL champ Chicago, showing more pop with the addition of Roy Sievers and once-and-current White Sock Minnie Minoso; and, more surprisingly, the Baltimore Orioles, buoyed by a starting rotation called the “Kiddie Corps,” so nicknamed since four of their starters were age 22 or younger. The Yankees emerged from a tight race in early September and, letting the White Sox and Orioles know they weren’t looking back, won their last 15 games of the regular season to easily nab the AL pennant.

New York pitching was superb and, as always under Stengel, the wealth was shared, with Art Ditmar leading the team with just 15 wins. Offensively, the real sparkplug to New York’s overall renewal came from first-year Yankee Roger Maris; the former Kansas City Athletic slammed 39 home runs and led the AL in slugging percentage (.581) and RBIs (112). Maris barely edged out Mantle for the AL Most Valuable Player award; little did the voters realize the encore Maris had in store for them in 1961.

The Pittsburgh Pirates victoriously opened the World Series by putting an end to the Yankees’ 15-game win streak; Bill Mazeroski’s continued improvement at the plate paid off with a two-run bleacher shot midway through that helped decide a 6-4 win. The Yankees didn’t react to the loss so much impressed as they were ticked off—promptly destroying the Pirates in Games Two and Three by scores of 16-3 and 10-0. The resulting momentum, added to the fact that the next two games were scheduled at Yankee Stadium, suddenly gave the Series all the assumed trappings of an early Pittsburgh surrender.

But revived Pirates pitching chewed apart both the momentum and the home field advantage. Starters Vern Law and Harvey Haddix sparked an unlikely turnaround by sedating New York bats and winning Games Four and Five, respectively, by scores of 3-2 and 5-2. Mazeroski again was pivotal at the plate, doubling home the decisive run in Game Five.

Just like that, after being on the verge of annihilation, the Pirates were headed back to Forbes Field with two games to win one and the world title.

And all the Yankees did was get mad again. Game Six set off another tirade of destruction by the Bronx Bombers, who obliterated the Pirates 12-0 behind 17 hits and Whitey Ford’s second shutout of the Series.

BTW: The Pirates were shut out just four times during the entire regular season.

They Looked So Good on Paper…

No World Series loser has come close to matching the offensive firepower exhibited by the Yankees in their seven-game defeat to the Pirates.

Game Seven would become a microcosm of the entire Series to the moment—a classic and vicious seesaw battle, a contest seldom lost on baseball fans both hardcore and otherwise.

The Pirates sprinted out to a 4-0 lead after just two innings, and it stayed that way until the fifth when the Yankees received a solo home run from Bill Skowron. That was the murmur. The clang came in the sixth with four runs, capped by a towering home run from Yogi Berra that managed to barely stay fair down the right-field line. New York added apparent insurance with two runs in the eighth to extend their lead to 7-4.

The real drama was still to come, a drama that would accelerate with each half-inning.

After Gino Cimoli pinched hit for Roy Face and singled to lead off the bottom of the eighth, signs of a Pirates rally looked to be on their way to extinction when the next batter, Bill Virdon, hit a double play grounder towards Yankees shortstop Tony Kubek. But the ball hopped wildly in front of Kubek, punching him square in the throat and knocking him back. Instead of two outs and nobody on, the Pirates had two on and no one out. The Pittsburgh rally had flared anew. And the Yankees would pay for it.

BTW: Kubek departed and was taken to the hospital with a bruised larynx.

Both runners scored, two more got on base and two others were retired when back-up catcher Hal Smith—a one-time Yankees prospect—launched a three-run homer to climax a five-run rally and send the Bucs to the ninth, suddenly, with a 9-7 lead.

The Yankees fought back in the ninth. After Mickey Mantle singled to score one run and bring the tying run to third with one out, Berra hit what appeared to be the Series-ending double play to first baseman Rocky Nelson, who stepped on first for one out, then began to throw to second to nail Mantle—only to realize that Mantle was scrambling back to first. Nelson reacted too late and Mantle got back to first safely without being tagged. While all of this frenzy was taking place, the tying run (pinch runner Gil McDougald) scored.

The Pirates responded in the bottom of the ninth not with a massive rally but with a single stroke of the bat. Bill Mazeroski, the only batter in the lineup who didn’t hit in the five-run eighth, was the only batter the Bucs needed in the ninth. After taking the first pitch from Yankee pitcher Ralph Terry, Mazeroski swung and sent the next pitch over the ivied brick wall in left-center to finish, perhaps, baseball’s most memorably wild game ever. Forbes Field erupted, and Mazeroski had to run the gauntlet of teammates, fans and police just to finish circling the bases.

Whatever Happened to the Mazeroski Ball?

Fourteen-year-old Andy Jerpe decided to leave Game Seven at Forbes Field early so he could help his mom prepare dinner back home when, walking behind the left-field fence outside the ballpark, Bill Mazeroski’s famous game-winning home run landed just a few feet away. He picked it up and, as the area quickly swelled with delirious fans, was rushed by team officials to the victorious Pirates’ clubhouse where he offered the ball to Mazeroski—who declined, saying the memories were enough.

Jerpe hung onto the ball and kept it in his room until, next spring, he and his friends needed a ball to play in a nearby field. An errant hit took the Mazeroski ball into a side area full of tall grass and weeds; after a frantic one-hour search, the kids never found it back. It is estimated that had Jerpe held onto the precious memento for 50-plus years, he could had sold it for up to a million dollars.

As Pittsburgh celebrated into the fall, turmoil brewed in New York.

An emerging contingent of Yankees players and management were growing tired of Casey Stengel, and so they played the age card to get rid of him. The Yankees’ unsuccessful, Jekyll/Hyde-like performance in the World Series was all the fodder they needed.

A bizarre press conference on October 18 began with Yankees co-owner Dan Topping announcing Stengel’s firing in a most congenial style, stating that Stengel was being given $160,000 “to do with as he pleases.” Maybe the game had passed Stengel by, but his sense of humor surely hadn’t; he classically responded to his release by stating, “I’ll never make the mistake of being 70 again.”

BTW: Long-time Yankees general manager George Weiss, age 74, was also released.

In 12 years, Casey Stengel had given the Yankees 10 American League pennants and seven World Series championships. But for the Yankees, the song always remained the same: What have you done for us lately?

And if it wasn’t a World Series triumph, it wasn’t squat.

Forward to 1961: The Greatest Feat Ever Performed* Roger Maris experiences a year of triumph and troment as he threatens Babe Ruth’s season home run record.

Forward to 1961: The Greatest Feat Ever Performed* Roger Maris experiences a year of triumph and troment as he threatens Babe Ruth’s season home run record.

Back to 1959: Reinventing Dodger After a lackluster California debut, the Los Angeles Dodgers victoriously adapt to their new surroundings.

Back to 1959: Reinventing Dodger After a lackluster California debut, the Los Angeles Dodgers victoriously adapt to their new surroundings.

1960 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1960 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1960 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1960 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Former catcher Gus Triandos discusses his baseball life and the game today in the only loving way he can—with a salty, self-deprecating tongue.

Former catcher Gus Triandos discusses his baseball life and the game today in the only loving way he can—with a salty, self-deprecating tongue.