THE YEARLY READER

1991: From Worst to First

The Atlanta Braves and Minnesota Twins achieve success in a way no team had done before—meeting in a highly charged World Series a year after both had finished in last place.

An extra-inning, walk-off home run by Kirby Puckett in Game Six of the World Series kept the Minnesota Twins’ championship hopes alive; pitcher Jack Morris would take it from there in the decisive seventh game. (Associated Press)

In the long histories of the National and American Leagues, there had been 245 last-place teams through 1990. Not once had any of them come back to place first the following year. It didn’t matter if such cellar dwellers represented the bottom of an eight-, 10- or 12-team league, or a six- or seven-team division; the historical odds of a quick rebound were zilch and growing worse with every year.

Making up for lost time, the 1991 season would mark a turnaround for the tail-enders. It wasn’t merely revenge, but a flat-out assault—with two teams, not one, roaring upwards from the basement to clinch league pennants in unprecedented fashion, ultimately engaging in one of the most thrilling World Series of this or any other age.

The Minnesota Twins were not exactly known as perennial laughingstocks; they fielded solid talent and were only three years removed from a world championship. Yet their 1990 record of 74-88, while not one to stink up the joint, was the worst among seven teams in the AL West, so the stigma was there as the official defending chumps. There was plenty of blame to go around, from an inexperienced pitching rotation to an awful defense to statistical regression from reliable All-Stars Kirby Puckett, Kent Hrbek and third baseman Gary Gaetti—whose recent conversion to Christianity seemed to take the fight out of his once-fiery leadership and increased tensions in a not-so-spiritual clubhouse.

BTW: Gaetti would be gone in 1991, signed as a free agent by the California Angels.

Two major free agent signings for 1991 were met with guarded optimism from Twins fans. Chili Davis was brought in as the team’s designated hitter, but he’d never been known as a power hitter and had smacked only 12 home runs the year before with the California Angels. Also signed was Jack Morris, the revered Detroit Tigers pitching ace who had become well known as the winningest pitcher of the 1980s. But this was the 1990s, and Morris spent the first year of the new decade at Detroit among the game’s losingest, with 18.

After a 2-9 start that suggested nothing had changed, the Twins scratched their way back to the .500 mark by Memorial Day, and then startlingly began June with a 15-game win streak—the longest since the team moved from Washington in 1961. Catapulted into first place, the Twins stayed there for all but a day the rest of the season against an AL West so competitive, the Angels—dropped to AL West Hell as Minnesota’s replacement at the bottom—finished at 81-81, 14 games back of the Twins’ AL-best 95-67 mark.

BTW: The Twins’ 15-game win streak fell short of the franchise record of 17, set by the 1912 Washington Senators.

The performances of Davis and Morris helped unwind and relax the tightly-crossed fingers of the Twins’ front office. Davis quickly proved he could slug it out amongst the best of them and finished the year with 29 homers, adding 93 runs batted in and a respectable .277 average punctuated with 95 walks. Morris, a Twin Cities native, felt at home on the mound for the first time in years with an 18-12 mark, 3.43 earned run average and 10 complete games.

There was a bonus element to the Twins’ sudden success with the rise of several youngsters. Two dramatically improved young pitchers—Scott Erickson (20-8, 3.18 ERA) and Kevin Tapani (16-9, 2.99) accompanied Morris in the starting rotation, while on offense, the veteran hitters were given something to drive in with the emergence of rookie second baseman Chuck Knoblauch (.281 average, 25 stolen bases).

The Twins’ express elevator ride lifted them from the bottom floor to a penthouse abandoned by the Oakland Athletics, whose almighty three-year AL reign abruptly ended from age, collapsed starting pitching, spotty hitting at best and some internal turmoil. It was hard to imagine that in spite of it all, the A’s still salvaged a winning season at 84-78, fourth in the West.

Like the Twins, the AL East-winning Toronto Blue Jays had regrouped behind a roster makeover that yielded improved results from new arrivals: Second baseman Roberto Alomar and outfielders Joe Carter and Devon White. The trio would provide the nucleus of a mini-dynasty in the coming campaigns, but for now they were, along with the rest of the Blue Jays, fodder for the energized Twins at the ALCS.

BTW: Alomar and Carter were traded from San Diego for Fred McGriff and Tony Fernandez; White was signed as a free agent to replace the departed, mercurial George Bell.

Proving that they would not collapse on the road as they did throughout their championship season of 1987, the Twins followed up a two-game split at home to start the ALCS by hammering the Blue Jays in all three games played at Toronto’s Skydome to take the AL pennant. Jack Morris won both of his series’ starts, Kirby Puckett followed up another lightweight season of slugging (15 home runs) with a pair of blasts in the final two games among seven other hits, and the Twins’ bullpen—heretofore a weak presence—didn’t allow a single run in 18.1 innings of work.

BTW: The Blue Jays, 57-27 with the Skydome roof closed since its 1989 debut, were only 1-5 with it shut in the postseason.

That the Twins arose from last place to American League champions was surprising. That their World Series opponents, the Atlanta Braves, were able to do the same in the National League was positively shocking.

While Minnesota had skimmed off the bottom in 1990, the Braves were there as they always had—as a truly bad team. They hadn’t enjoyed a winning year since 1983 and over the previous three seasons had finished last in the NL West with an average of 100 losses and attendance under a million. Misguided marketing added to the team’s misery when, in 1990, it decided to use actor Jim Varney’s hayseed caricature Ernest P. Worrell (“Hey, Vern!”) as the team’s pitchman. The stereotype offended Braves fans.

In earlier days, Atlanta owner Ted Turner would have macro-managed from far and near to fix things, but more recently he had more important items on his agenda such as building world peace and colorizing MGM movie classics, leaving his Braves as a black-and-white retread.

Bobby Cox held the minority opinion that there was a good thing going in Atlanta with the Braves. He had to think that way; the once-and-current Braves manager had returned to Atlanta in 1985 as its general manager, following a frustrating tenure at Toronto in which he awoke the Blue Jays to prominence, but not a World Series. Cox patiently rebuilt the Braves from the bottom, producing a sack full of prospects—and making sure they wouldn’t get rashly traded away for now-or-never veterans. The untouchables included outfielders David Justice and Ron Gant, infielders Mark Lemke and Jeff Blauser, and pitchers Tom Glavine and Steve Avery.

BTW: Cox’s first tour of duty with the Braves, from 1978-81, produced only one winning year—a 81-80 mark in 1980—before turning the Blue Jays around.

Seems So Long Ago, And Yet…

The Braves languished badly through six years of misery that made their victorious 1991 about-face all the more remarkable.

Along with the current Atlanta GM—the highly-revered John Schuerholz, plucked away from Kansas City—Cox rounded out the edges to a team on the brink of a stunning turnaround in 1991 with a series of astute roster moves, adding two veterans who excelled into uncharted personal excellence.

Stolen from Montreal was Otis Nixon, a part-time performer who in eight previous years was all run, no hit. In Atlanta, Nixon suddenly developed into a top-flight, everyday leadoff artist, batting .295 with 72 steals. But Nixon’s value was dwarfed by what Terry Pendleton would give to the Braves. A respectable ballplayer who endured rocky times of late—bottoming out in 1990 with a career-low .230 average—the more relaxed and patient Pendleton turned his $1.7 million Atlanta salary from an extravagance to a bargain, leading the NL with 187 hits and a .319 batting average. He added personal highs in all power categories, including home runs (22), and become the spiritual anchor of a baseball revival in the Deep South.

Atlanta started well but entered the All-Star break at 39-40, 9.5 games behind the front-running Los Angeles Dodgers in the NL West. Skeptics sensed that Atlanta had played over its head and was coming back down to hard earth, but instead the Braves were ready to go full throttle with a second wind—building up confidence while narrowing the Dodgers’ lead. From mid-August, the Braves would engage the Dodgers in a seesaw dogfight to the wire, where Atlanta would take the West by a game thanks to an eight-game win streak in late September.

BTW: While the Braves were going worst-to-first, the Cincinnati Reds headed in the opposite direction; at 74-88, the Reds produced the worst record by a defending World Series champion to date.

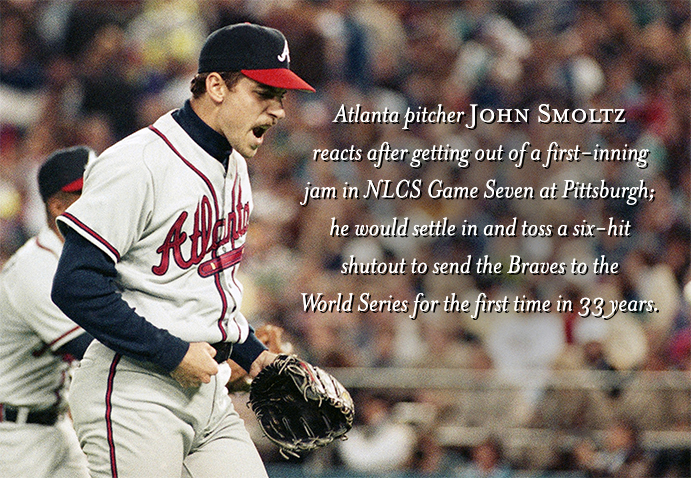

The Braves’ second-half thrust to the postseason was not without obstacle. Injuries befell the team and, three weeks before the playoffs, Otis Nixon’s breakthrough year was busted up when he tested positive for cocaine, resulting in a season-ending suspension. But youthful pitching picked up the Braves. Left-hander Tom Glavine notched 20 wins against 11 losses; fellow southpaw Steve Avery—all 21 years of him—was no less impressive at 18-8; and 24-year-old right-hander John Smoltz overcame a miserable 2-11 first half with the help of hypnosis to finish at 14-13.

The Pittsburgh Pirates reached the NLCS for the second straight year, this time with considerable ease—topping second-place St. Louis with the majors’ best record at 98-64. Harmony had little to do with it. Star slugger Bobby Bonilla (.302, 18 home runs, 100 RBIs) was certain to leave the financially-challenged Pirates at the end of the year, and all-world Barry Bonds (.292, 25 homers, 116 RBIs) was sure to follow—especially after a spring training meltdown with manager Jim Leyland that was caught on camera.

BTW: The Pirates kept the Cardinals, the NL East doormats of 1990, from becoming baseball’s third worst-to-first ballclub in 1991.

(Associated Press)

Against the Braves, the Pirates’ stars played as if they had already fled. Bonds hit an empty .148, Bonilla an innocuous .304 (seven hits, one RBI). Pitcher John Smiley, a pleasant surprise who tied Glavine for the NL lead with 20 wins—and a man also rumored to be salivating at the idea of free agency—bombed horribly, lasting a total of 2.2 innings over two starts, allowing seven earned runs.

All this, and the Pirates still nearly slipped past Atlanta. They took a three-games-to-two lead home to Pittsburgh and needed just that one win. They couldn’t even get one run. Steve Avery, who pitched 16.1 scoreless innings over two sensational starts for the Braves, kept the Bucs locked down in a 1-0 Game Six win and, in Game Seven, John Smoltz fired a six-hit, 4-0 shutout to send the Braves, one year removed as baseball’s worst team, to the Fall Classic.

Given the similar paths that the Braves and Twins had taken throughout the 1991 season—initial little prospects, slow starts, strong finishes, rekindled play by their veterans, accelerated development by their youngsters—there was little wonder that the World Series they were about to embark on would be one of the tightest ever. The series would go the distance, with five of the seven games decided by a run, three in extra innings, and four in the last at-bat. Heroes were made of common players such as back-up Minnesota infielder Scott Leius (a game-winning homer in Game Two) and Atlanta second baseman Mark Lemke (10 hits, including three triples), while villains were made of stars like Twins first baseman Kent Hrbek, who in Game Two killed an Atlanta rally when he appeared to muscle the Braves’ Ron Gant off the first base bag, tagging him for the out. Somehow, umpire Drew Coble let the play stand, infuriating the Braves and their fans.

BTW: Hrbek received several death threats when the series moved to Atlanta; one Braves fan put up a sign that said, “Hrbek is a Jrk.”

After the Braves exploded for a 14-5 rout in Game Five to take a 3-2 series lead back to Minnesota, the best dramatics still lay ahead. Game Six completely belonged to Kirby Puckett; the dynamic Twins center fielder robbed Gant of a possible homer with a leaping catch, and at the plate he tripled and knocked in three runs—the last of which came on a dramatic leadoff homer in the 11th inning to force Game Seven, 4-3.

Jack Morris eyed making his second straight start on three days’ rest for the winner-take-all finale, but he had to talk Minnesota manager Tom Kelly into it—reminding him that his next start would be on 150 days’ rest. Kelly obliged, and Morris proceeded to deliver one of baseball’s greatest pitching performances. But John Smoltz wasn’t going to make it easy for him.

Smoltz, the Michigan native who grew up idolizing Morris, matched him zero for zero over seven innings, and looked ready to be the benefactor of the game’s first run in the eighth when Terry Pendleton launched a drive to the wall in right-center. But Lonnie Smith, running from first, got suckered into a force-out decoy at second base by Twins infielders; his brief hesitation cost him a chance to score on the double, and he settled for third base. And that’s where Smith remained when Sid Bream grounded into a double play to end the Braves’ threat.

The Twins finally knocked out Smoltz in the bottom of the inning, but double plays knocked the Twins out of their own rallies in the eighth and ninth innings. Morris, determined to go whatever the distance called for, pitched a perfect 10th—and then the Twins finally delivered. Dan Gladden led off the bottom of the 10th with a classic bloop double on the Metrodome’s artificial turf, was bunted over to third—and with every Braves fielder playing in by necessity, utility benchwarmer Gene Larkin added his name to the list of unlikely Series heroes when he punched a grounder through to bring home Gladden with Game Seven’s first, only and winning run.

BTW: Between two World Series triumphs in 1987 and 1991, the Twins would never lose at the Metrodome (8-0)—and never win on the road (0-6).

Rising above the roll call of unlikely heroes in Leius, Lemke and Larkin was the unlikely performance of Morris, whose beyond-the-call, 10-inning shutout instantly became the stuff of legends, making him a hometown hero in his first—and only—year in a Minnesota uniform.

Turning baseball upside down with their turnabouts and shaking it all around with their roller coaster World Series, the Twins and Braves set the tone for a decade full of sudden winners and losers whose stock fell and rose with all the elasticity of a yo-yo. Curse all you want at baseball’s heartless economics that created such fluctuations, but the fun it gave the game’s fans in 1991 can never be dismissed.

Forward to 1992: Truly, A World Series After years of strong play, the Toronto Blue Jays finally reach the top and become baseball’s first international champions.

Forward to 1992: Truly, A World Series After years of strong play, the Toronto Blue Jays finally reach the top and become baseball’s first international champions.

Back to 1990: The Dynasty Dies Nasty Armed with a tough, rough and rowdy trio of relievers, the Cincinnati Reds knock off the almighty Oakland A’s.

Back to 1990: The Dynasty Dies Nasty Armed with a tough, rough and rowdy trio of relievers, the Cincinnati Reds knock off the almighty Oakland A’s.

1991 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1991 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1991 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1991 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.