THE YEARLY READER

2001: Raising Arizona

High-rolling Jerry Colangelo survives the ups-and-downs of his Arizona Diamondbacks’ infant years, attempting to bring home a World Series trophy against the New York Yankees—uniquely cast as sentimental favorites in the aftermath of 9-11.

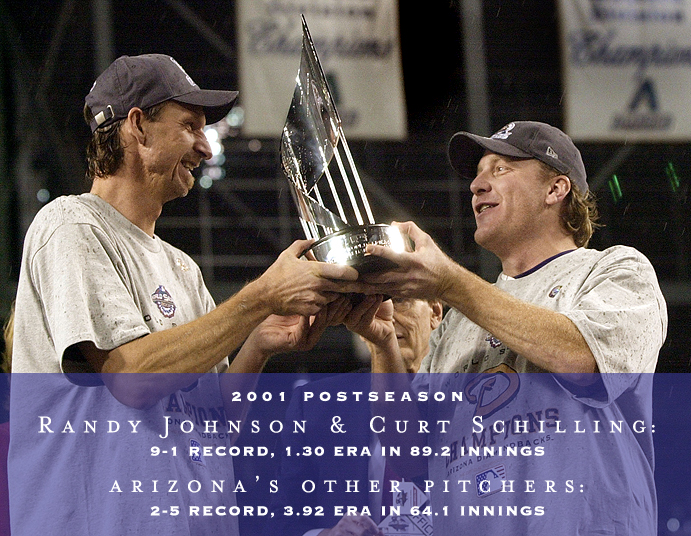

Arizona pitchers Randy Johnson (left) and Curt Schilling together hoist the World Series MVP trophy, for which they both shared. (Associated Press)

There is an unwritten rule in baseball: Any expansion team must be born to suffer and pay its dues over its first three years, if not longer.

Jerry Colangelo wouldn’t have abided by that rule had it been tattooed backward on his forehead to help him read it in the mirror.

The owner of the Arizona Diamondbacks had no intention of becoming an expansion lackey for baseball’s established lords. Shove the baby steps, insisted Colangelo; he was determined to be an instant player with the big boys, and they were going to like it. Of course, they didn’t.

Colangelo’s wild spending habits became the stuff of urban legends over his first few years as the Diamondbacks’ front man, but amid all the red ink was one very nice return on his start-up’s investment: A world championship in just its fourth year of existence.

It could be argued that, during the 1990s, Colangelo was the most powerful man in the state of Arizona. He arrived in Phoenix three decades earlier as a very young general manager of basketball’s Suns, and from there built himself up as a man of many things; whatever he wanted, he got. He purchased the Suns, helped bring the Super Bowl and National Hockey League to town, and successfully led the effort to bring in a Major League baseball franchise. Colangelo lobbied and got sparkling new facilities for both the Diamondbacks and Suns.

Colangelo had a generous reputation for doling out dollars, as many of the original Diamondbacks players found out in 1998. He first racked up veteran infielder Jay Bell for five years and $34 million—far above what anyone else considered paying. He then acquired slugger Matt Williams, so desperate to play near his Phoenix home that he would have played for peanuts—but Colangelo instead gave him $45 million over five years. Catcher Jorge Fabregas lost an arbitration case against the Diamondbacks and was ready to settle for $875,000 when Colangelo threw it out and gave him a two-year contract at nearly $1.5 million a year—the same amount Fabregas had fought for in arbitration. Over the next few years, lofty Arizona payouts were awarded to superstar pitcher Randy Johnson ($65 million over five years) and somewhat-star pitcher Todd Stottlemyre ($32 million over four years). Colangelo’s mortified fellow owners wondered: With guys like this, who needs a players’ union? The joke started circulating that the team should be renamed the Greenbacks.

The Diamondbacks lost 97 games in their inaugural year but did a stunning about-face in 1999 by winning 100 to take the National League’s Western Division—before bowing out in the postseason’s first round to the New York Mets. They remained competitive for 2000 but did not make the playoffs, and the question arose: What was more likely to happen first with the Diamondbacks, a World Series title or bankruptcy?

Scoffing at the Training Wheels

The Diamondbacks showed tremendous impatience out of the starting block, reaching the postseason— and winning their first World Series—faster than any of the other 13 major league expansion teams since 1961.

Even with near-maximization of revenue—the Diamondbacks had corporate sponsorship for practically every nook and cranny of Bank One Ballpark, which fans often filled—the franchise was said to be suffering serious financial pain. Colangelo raised ticket prices, asked team investors to fork over $50 million to keep the checking account solvent, got another $46 million from deferred salaries, and laid off front office personnel. All this while rumors floated that the Diamondbacks—and especially Colangelo—were actually operating in the black. Colangelo showed sensitivity to such issues when, after being prodded about his personal gains during an interview with Armen Keteyian for HBO’s Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel, he profanely stormed off the set.

On the field, the Diamondbacks entered 2001 with an equal mix of questions, promise and pressure. They replaced abrasive first manager Buck Showalter with the more emotionally unbuttoned Bob Brenly—a former catcher who had never managed at any level, and most recently had been the broadcast analyst for both the Diamondbacks and Fox Sports. Brenly would be presiding over a highly veteran team (average age: 32) that wasn’t getting any younger, but had gotten more formidable on the mound with the addition of Curt Schilling—who with Randy Johnson formed one of the most feared and exciting one-two pitching punches the game had seen in years.

After a weak start, the Diamondbacks put together one nine-game winning streak in May to jump into the NL West race, and another in August to pull away from the division’s two prime contenders, the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers. All along, the left-handed Johnson and right-handed Schilling hummed along as, clearly, the two best pitchers in the NL, further excelling in a healthy duel to see who would be the best. Statistically, it was a judgment call. Schilling had a slight edge on record, 22-6 vs. 21-6; Johnson had the better earned run average, 2.49 vs. 2.98; and although Schilling struck out 293 (while walking just 39), Johnson blew past him and everyone else with 372—just 11 shy of Nolan Ryan’s all-time mark.

BTW: Cy Young Award voters would give the ultimate nod to Johnson, with 30 first-place votes compared to Schilling’s two.

At the plate, the Diamondbacks were carried by the gargantuan efforts of the physically unassuming Luis Gonzalez. Three years earlier, the good-natured Gonzalez had radically opened up his batting stance—and as a result, his power numbers grew on a consistent, yearly basis. In 1999, Gonzalez set career highs with 26 homers and 111 runs batted in; in 2000, he upped it to 31 and 114. In 2001, he went off the charts—crushing 57 homers to go with 142 RBIs and a .325 batting average.

Barry Bonds watches the flight of his 73rd home run on the final day of the season, two days after he had broken Mark McGwire’s three-year-old mark. (Associated Press)

As he had been for much of the 1990s, Bonds remained the game’s most dangerous hitter. Most players begin to exhibit career decline as they reach their late 30s, but the opposite seemed true of Bonds, who turned 37 with a much more prodigious offensive game.

A year earlier, Bonds had set a personal best by slamming 49 home runs for the Giants; in 2001 he was closing in on a repeat—at the All-Star break. Many opined that Bonds was spiking with a record 39 first-half homers, but he actually was setting the pace. Bonds never slowed nor wavered—even as opposing pitchers did all they could to keep him from receiving a hittable pitch.

BTW: Bonds set a major league record for walks in 2001 with 177; he would break it again a year later with 198, and once more in 2004 with an unbelievable 232.

When Musclemen Ruled the Earth

Through 1994, major leaguers had hit 50 home runs in a season 18 times. It would take only eight years—from 1995-2002—to match that total in a period eventually known as the Steroid Era. During this time, the previous season record of 61 homers belted by Roger Maris in 1961 would be eclipsed six different times.

Mark McGwire had shattered Roger Maris’ fabled mark of 61 home runs by nine in 1998, and that new bar was considered secure; yet, barely three years had passed, and now McGwire’s 70 was about to be erased from the record books. Bonds would take care of that when, in the third-to-last game of the season, he hit home runs #71 and #72 off the Dodgers to become the latest season home run king. He added the exclamation point on the season’s final day, lofting #73 off Dodgers knuckleballer Dennis Springer into a sea of near-riotous fans atop Pac Bell Park’s right-field wall desperate for a famous, potentially lucrative souvenir.

BTW: Who held ownership of Bonds’ 73rd home run ball fell into legal dispute; two years later, a judge ordered the two claimants to sell the ball and split the proceeds. The final sale price didn’t even cover their legal fees.

Bonds’ sudden power surge into record territory was not without controversy; media pundits, fans and even fellow players squinted their eyes in suspicion and wondered aloud how a guy in his late 30s could put on 30 pounds of muscle overnight. Bonds attributed such results to a strength and conditioning program and, using his usual abrasive disposition towards the press, waived away in disgruntlement any suggestions of doping as falsehood.

Legit or otherwise, Bonds replaced McGwire, but who knew for how long; in a continued era of outrageous offense, it seemed wisest to use pencil, not pen, to write in Bonds as the new one-year home run king.

The other major achievement of 1998—that of the American League-record 114 wins notched by the New York Yankees—would also fall by the wayside.

Safeco Field had opened at Seattle in 1999 as a savior for the Mariners, generating major revenue that would allow the team to retain its superstar hitters. Instead, the new ballpark’s expansive outfields scared them away: Ken Griffey Jr. bolted after 1999, followed a year later by Alex Rodriguez.

Rather then spend tens of millions on one player to replace the departed All-Stars, the Mariners wisely committed the freed-up dollars to solid, not star, talent to produce a roster with few holes. Before 2001, only a few casual baseball fans had likely heard of players like Bret Boone, Mike Cameron, Freddy Garcia and Jamie Moyer. And Ichiro Suzuki? Even the most dedicated, 24/7 baseball nut had nary a clue.

One hundred and sixteen regular season victories later, a whole lot of people suddenly knew who these Mariners were.

First-year Japanese import Ichiro Suzuki became the embodiment of the 2001 Seattle Mariners, who like Suzuki slashed and dashed their way to a record-breaking 116 wins. (Associated Press)

Boone, a third-generation big leaguer, made pop Bob and grandpa Ray proud, setting family highs with a .331 batting average, 37 home runs and 141 RBIs. Cameron contributed 25 homers and 110 RBIs, and his sensational play in center field made Griffey’s memorable defense look passé. Garcia led the AL in ERA (3.06) and innings (238.2) while producing an 18-6 record, while Moyer went 20-6 at age 38.

But the most heralded of Seattle’s previously unheard-of was Suzuki, who had ripped apart Japanese baseball and proved, as a 27-year-old rookie in America, that major league pitchers were no better. Often referred to only as Ichiro—like a Brazilian soccer star—Suzuki led the AL in hits (242), average (.350), steals (56) and Japanese media reporters hounding his every move in the States.

BTW: Suzuki’s 242 hits were the most by a major leaguer in 71 years; three seasons later, he would break the all-time mark with 262.

Under veteran manager Lou Piniella, the Mariners’ 116-46 record was consistently superb, no matter which way you split it up. They won 57 at home and 59 on the road; they suffered only one losing streak greater than two; they never lost more than nine in any one month; and they won at least twice as many games as they lost against every team they played.

Seattle’s .716 winning percentage trailed only the 1954 Cleveland Indians (.721) for the AL’s all-time best. Yet the 2001 Mariners would share something else in common with the 1954 Indians: Season-ending disappointment.

One More Reason We Blew up the Kingdome

For much of the 1990s, the Mariners were a talented team whose pitchers were tortured trying to survive in the bandboxed Kingdome. But after the team’s move to spacious, damp Safeco Field in mid-1999, the fortunes of Mariners hurlers improved dramatically—and thus, so did those of the team. It all peaked for Seattle in 2001.

After the Mariners received a tough first-round playoff test from the modern-day Indians—having to win the series’ final two games to advance—Seattle readied for an ALCS rematch against the Yankees, a team not only looking for a fourth straight World Series title, but also a group of individuals hoping to give New York City an emotional lift after the traumatic September 11 attack on the World Trade Center by Islamic terrorists.

The Yankees had repeated with ease in the AL East thanks to continued solid starting pitching, from free agent pick-up Mike Mussina (17-11, 3.15 ERA) and Roger Clemens—who two years after winning 20 decisions in a row put together a 16-game win streak to help start his year at 20-1, before losing his final two decisions.

In the ALDS, the Yankees were threatened with a three-and-out against the wild card Oakland A’s—who at 102-60 had the misfortune of playing in the same division as Seattle. But shortstop Derek Jeter saved Game Three, the series—and the season—as the A’s Jeremy Giambi scampered toward home on a likely game-tying double by Terrence Long; Jeter came out of nowhere to take an errant throw near home plate from outfielder Shane Spencer, and somehow delivered an off-balance shovel toss on time to catcher Jorge Posada, who put the tag on Giambi—who until that instant didn’t feel compelled to slide. Considered one of the greatest defensive plays in modern times, “The Flip” completely reversed the series’ momentum, which fell squarely in the Yankees’ favor as they delivered a five-game series triumph.

The Mariners were no luckier than the A’s. The Yankees critically began the ALCS with two wins on the road at Seattle, then after absorbing a 14-3 loss in Game Three in New York, broke open Game Four in the late innings, 3-1—and broke it open early in Game Five, storming to a 12-3 rout to put a disheartening coda on an otherwise overpowering Mariners opus.

Having mastered the Mariners to conquer the AL, the Yankees re-entered the World Series against the Arizona Diamondbacks with the enormous task of upstaging the two fireball stars that made up “The Schilling & Johnson Show.”

The twin Diamondbacks aces had already rendered their first two postseason opponents—the St. Louis Cardinals and, in the NLCS, the Atlanta Braves—impotent at the plate. Between them, Schilling and Johnson started six of the 10 games in those first two rounds—winning five with four complete games, striking out 58, and producing a 1.24 ERA that seemed to make the rest of the Arizona staff (at 4.74) mere extras spending downtime in the bullpen.

The fresh scars of 9-11 enshrouded the World Series. Security at both ballparks—particularly at Yankee Stadium, just nine miles from Ground Zero—was intense; all nearby air traffic, including the blimp hired for network TV aerials, was banned; and in an utterly emotional tribute, the tattered American flag that survived the collapse of the World Trade Center was flown at Yankee Stadium.

Adopted as sentimental Series favorites, the Yankees ran into trouble right away in the first two games at Phoenix. Schilling allowed just a run on three hits over seven innings in Game One, and Johnson threw a three-hit shutout in Game Two; the Diamondbacks rolled in both games, 9-1 and 4-0. Finally, the other Arizona starters became inspired. Brian Anderson and Miguel Batista pitched wonderfully for the Diamondbacks in, respectively, Games Three and Five, and sandwiched in between them was Schilling, who produced a virtual clone of his Game One start in Game Four. But the Diamondbacks lost all three games—the last two when closer Byung-Hyun Kim gave up, on consecutive nights, two-run, two-out, game-tying homers in the ninth that set up extra-inning wins for the Yankees.

BTW: Some folks sarcastically nicknamed the Korean-born Diamondbacks closer as “Hung One Kim” in quick retrospect.

After scoring just six runs in their three losses at New York, Diamondbacks bats came roaring back to life for Johnson with a 15-2, Game Six rout of the Yankees at Phoenix. But Arizona manager Bob Brenly was criticized for not preserving Johnson for possible Game Seven relief by leaving the Big Unit in for seven innings—when he could have been removed after five with a 14-0 lead.

In a fantastic winner-take-all matchup at Bank One Ballpark, Schilling and Roger Clemens dueled into the seventh tied at 1-1, but up-and-coming second baseman Alfonso Soriano homered to lead off the eighth, unlocking the tie and knocking out Schilling.

Holding the 2-1 lead to the ninth, the Yankees brought in their deal-sealer: Mariano Rivera. The Panamanian-born closer had been all but automatic throughout his postseason career to date with a 0.70 ERA. But in his bid to garner a fourth straight World Series title to rival the Yankees of the late 1930s and early 1950s, Rivera became uncharacteristically unglued. He strengthened a desperate Arizona rally by throwing wild past second base on an attempted force play, then plunked Craig Counsell in a moment that ultimately led to a tie game and a bases-loaded situation for Luis Gonzalez. The 57-homer man ended the season not with a blast but with a bloop, a broken-bat job that barely cleared a drawn-in infield behind second and fell in between pinstriped defenders to score the Series-winning tally.

BTW: This was the second Series-winning rally involving Counsell; he scored the decisive tally for Florida in Game Seven of the 1997 Fall Classic.

Game Seven’s winning pitcher: Randy Johnson. There was enough gas left in him after all, retiring all four Yankee batters he faced at the end to keep the game close.

Jerry Colangelo not only savored the moment of triumph but also the added $16 million the postseason brought into his team’s coffers. Perhaps Colangelo could pay off some debts or keep an All-Star or two with the money. Whatever the amount, no dollar figure could equate the priceless feeling of conquering baseball’s top prize when other newborn owners would have been content just to field a team.

Forward to 2002: The Wild, Wild Card West The red-hot Anaheim Angels—riding high on the back of their “Rally Monkey”;—attempt to overcome Barry Bonds and the San Francisco Giants.

Forward to 2002: The Wild, Wild Card West The red-hot Anaheim Angels—riding high on the back of their “Rally Monkey”;—attempt to overcome Barry Bonds and the San Francisco Giants.

Back to 2000: New York, New York The first Subway Series in 44 years is spiced with antagonism thanks to an ongoing feud between Roger Clemens and Mike Piazza.

Back to 2000: New York, New York The first Subway Series in 44 years is spiced with antagonism thanks to an ongoing feud between Roger Clemens and Mike Piazza.

2001 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2001 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2001 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2001 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.