THE YEARLY READER

2003: Curses, Inc.

The Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox solidify their historic reputations as baseball’s two unluckiest teams, and deepen the belief among many that they’re both destined for eternal suffering—but is that a curse, or a blessing?

Chicago Cubs outfielder Moises Alou has a fly ball infamously stolen away by Wrigley fan Steve Bartman; the New York Yankees’ Hideki Matsui pounds the exclamation point on a crippling rally that once again helped seal the Boston Red Sox’ fate shy of glory. (Associated Press)

No major league baseball team had gone longer without winning a World Series than the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox. Entering 2003, there unlikely was anyone alive who bore witness to the Cubs’ last championship in 1908, while maybe a few were around to chat first-hand about the Red Sox’ last hurrah in 1918. The Chicago White Sox, who actually last won it all a year before Boston, are arguably exempt since they should have won it a year later, in 1919—but eight of their players decided to give it away for a price.

Both the Cubs and Red Sox have endured repeated heartbreaks in their quests to return to the top. The Cubs were good enough to reach the World Series seven times through World War II, but lost them all. They hadn’t been back since. The Red Sox had been there once every generation, but someone always messed it up for them, whether it was Johnny Pesky hesitating a relay throw in 1946, Dick Williams prematurely bragging about “Lonborg and Champagne” in 1967, or Bill Buckner letting the ball go through his legs in 1986.

The continued failures defied logical explanation. People began to believe something higher was at work. Such theories gave rise to the curses: The one placed on the Red Sox after Babe Ruth was sold to the New York Yankees in 1920, and the one placed on the Cubs by a tavern owner whose goat was refused entry into Wrigley Field for the 1945 World Series.

With each passing year, through every defeat snatched from the jaws of victory, as both teams annually finished second to someone else, each curse became a skewed blessing so rich in tradition, it had practically developed into a brand that could be licensed and profited from. Heavens forbid if the Cubs or Red Sox actually won a World Series; such an event would violate corporate guidelines, ruin the mystique and return the team to Earth as just another major league ballclub.

In 2003, both the Red Sox and Cubs were mere outs away from facing one another in a World Series to decide whose curse would finally fall. Instead, they enhanced their aura even more by finding new ways to be denied.

Adding insult to injury, a World Series that appeared ready to reward one of baseball’s long-suffering would instead go to an 11-year old wild card of franchises that still had yet to win a divisional title and, in only its second-ever finish above .500, won its second-ever World Series.

The Cubs’ road to eventual disappointment was led by manager Dusty Baker, who understood the hard pain of heartbreak after a decade of failing to reach the top with consistently good teams in San Francisco. As with the Giants, Baker connected in the Chicago clubhouse and became instantly respected by the roster he inherited—which included All-World slugger Sammy Sosa and a young, highly promising starting rotation of fireballers (Kerry Wood, Mark Prior, Matt Clement and Carlos Zambrano) that helped reset the all-time mark for team strikeouts at 1,404, which they broke the year before.

A player’s favorite as always, Baker’s warm and passionate presence was a perfect fit within the friendly confines of Wrigley Field, and it helped lift the Cubs to their first divisional title since 1989. Baker kept his club upright through a rather difficult first half for Sosa, who suffered a rare, prolonged power outage after a beaning incident at Pittsburgh cracked his batting helmet in two; an ensuing toe injury kept him out for 16 games, and once back, the still-slumping Sosa was caught using a corked bat. But Sosa’s knack for white-hot horsepower emerged in the second half, smashing 30 home runs over the Cubs’ final 80 games to help win the National League Central race in the final week over rivals Houston and St. Louis.

BTW: Sosa claimed he grabbed a batting practice bat by mistake; MLB checked out his other 76 bats, none of which tested positive for cork.

Always Choking, Never Clinching

After winning the first two games of the ALDS against the Red Sox, the A’s collapsed and lost three straight games and the series. For the hard-luck A’s, the defeats extended a postseason streak dating back to 2000 in which they lost nine straight potential series-clinchers.

The Red Sox, meanwhile, were nearly grounded through the season’s first few months by a horrendous bullpen that blew just about every lead handed to them by a steady base of starters (including effective yet fragile Pedro Martinez). But the hurlers’ woes were often made moot by an immensely productive batting order with no weak spots—as proven by American League highs in batting (.289), runs scored (961) and slugging percentage (an all-time record .491); Boston’s 238 home runs were just one shy of AL leader Texas. All-Stars like shortstop Nomar Garciaparra (.301 average, 28 home runs, 105 runs batted in) and left fielder Manny Ramirez (.325, 37, 104) were accompanied by a strong and capable list of supporters, no fewer than six of who knocked in at least 85 runs.

Under second-year manager Grady Little, whose previous claim to fame was managing the Durham Bulls while Bull Durham was being filmed, the Red Sox finished second to the Yankees—since 1918, they always seemed to—but were good enough to snare the AL Wild Card and stay alive for the postseason.

BTW: For those pining for parity in baseball, the AL East was a source of frustration; for the sixth straight year, all five of its teams finished in the same order.

Both the Cubs and Red Sox were expected to make quick bows out of the postseason as decided first-round underdogs. But they were facing teams that had made an astonishingly bad habit of underachieving in the playoffs: The Atlanta Braves and the Oakland A’s.

The Cubs, with the worst record (88-74) of any postseason participant, took on a Braves team that had the best (101-61)—and Chicago won three games to two, as Kerry Wood’s two sterling starts helped tame a prodigious Atlanta offense almost every bit as good as Boston’s.

The Red Sox, after losing the first two games to the A’s, fought back to take the series with three edge-of-your-seat victories, thanks mainly to a startlingly stingy contribution from an unlikely source: The bullpen, which shut down Oakland bats in the clutch.

Baseball fans, fanatical and casual alike, began to wax nostalgic about the possibility of a Red Sox-Cubs World Series to determine who best could exorcise their curse. But one step remained: Advancing past the League Championship Series.

The Red Sox had the unenviable task of knocking off the team they loved to loathe: The New York Yankees. The Cubs looked to have it easier, taking on a complete upstart in the NL Wild Card Florida Marlins.

In the owners’ contraction-enhanced merry-go-round of the past few years, Jeffrey Loria had escaped the derelict Montreal Expos by selling the franchise to Major League Baseball—and in exchange, bought the Marlins from John Henry, who was on his way to becoming the prime mover in a staggering $660 million purchase…of the Red Sox.

Assuming control of the Marlins in 2002, Loria might have wondered if he had it better in Montreal. The Marlins, still showing the aftereffects of Wayne Huizenga’s 1997 spending binge, had a trail of losing seasons, little bucks to work with and, in 2002, avoided finishing last in major league attendance when an unnamed person bought enough tickets in the Marlins’ final home game to push their season total just above that of the Expos’. Entering 2003, only four teams had lower payrolls than the Marlins.

Despite the addition of spirited bulldog catcher Ivan Rodriguez—who many thought the Marlins were taking a $10 million chance on, given the ex-Ranger’s recent penchant for serious injury—the Marlins started out 2003, as always, as a young team with some promise playing subpar baseball, well behind the Braves and expected chasers in the Expos and Philadelphia. Loria decided it was time to shake things up, so in mid-May he fired manager Jeff Torborg and replaced him with Jack McKeon.

BTW: In a bizarre sideshow, Loria and Florida general manager Larry Beinfest also fired pitching coach Ed Arnsberg—who was said to react violently to the news.

At 72, McKeon had managed sporadically since 1973 and had never made it to the playoffs, and he was viewed as another retread from the old boy’s network trying to keep someone’s house standing. But with apt father-figure guidance, McKeon did what most managers in his situation usually do; he told his players to go out and have fun, because no one expected them to win anyway.

As usual, the advice worked.

Under McKeon, the Marlins charged into winning territory and played the best baseball of any team in the season’s second half. They claimed the NL Wild Card and, in the NLDS, promptly foiled the NL West-winning Giants in five games, as Rodriguez led the way with total omnipresence in the clutch.

Rodriguez again provided the heroics in Game One of the NLCS at Chicago with five RBIs in an extra-inning victory, but when the Cubs won the next three games—giving the Cubs three games to win one and advance, at long last, to the World Series—it appeared that the Marlins’ magic had finally run out.

As the Cubs strolled early on, the Red Sox were all but at war with the Yankees in the ALCS. The flashpoint would be Game Three and a dream duel pitting Boston ace Pedro Martinez and ex-Boston ace Roger Clemens, who earlier announced that 2003 would be his final year. (It wouldn’t.) One of baseball’s longest-running cold wars boiled over when Martinez plunked the Yankees’ Karim Garcia in the back, and when Manny Ramirez overreacted to a high (but not tight) Clemens fastball a half-inning later, the dugouts emptied into an episode lowlighted when Yankees bench coach Don Zimmer charged Martinez—who grabbed the 72-year old by his bald head and shoved him to the ground. From all of this, no one was ejected, and Clemens and the Yankees prevailed, 4-3.

The Red Sox recovered by winning two of the next three games to force Game Seven—and a Martinez-Clemens reprise—at Yankee Stadium. Clemens was ineffective and gone after three innings, while Martinez sailed on, leading 5-2 after seven. But in the eighth, the Yanks got a run back, and Grady Little was ready to go to his bullpen. Months earlier, such a decision would have been fraught with danger, but the once beleaguered Red Sox relievers had become nothing short of spectacular in the playoffs, posting a sensational 1.14 ERA over 31.2 innings of work. When Little approached the mound, Martinez lobbied to stay in. He had thrown 115 pitches. The Red Sox bullpen was ready.

Little decided to stick with Martinez.

The next batter, Hideki Matsui—the Yankees’ first-year answer to Ichiro Suzuki—doubled his way on as the tying runner. He reached home one batter later when Jorge Posada hit a Texas Leaguer into short center field. Bang-bang, tie game.

Little decided to go the bullpen.

Neither team could unknot the 5-5 score through 10 and a half innings, but then New York third baseman Aaron Boone—brother of Bret, son of Bob, grandson of Ray—lofted Tim Wakefield’s first pitch of the Yankees 11th high, deep and into the left-field bleachers. Boom, game over. The Red Sox were cursed again.

All for One, None for All

For 17 straight years through 2003, the team with the majors’ highest-paid player failed to make the playoffs. In fact, only twice during this time did any of these teams even reach over the .500 mark. The streak would end in 2004 with Manny Ramirez making top wages of $22.5 million for the World Series champion Red Sox. (Source: baseball-reference.com).

Down three games to one, the Florida Marlins needed to breathe life back into their NLCS chances against the Cubs, and they got it courtesy of brash 23-year-old Josh Beckett, who threw a two-hit shutout in Game Five to extend the series back to Chicago.

After 58 years, a goat was finally spotted at Wrigley Field for Game Six. His name was Steve Bartman.

A 26-year-old little league coach who lived with his parents, Bartman was seated along the first row of Section 116 near the left-field foul pole, enjoying along with 40,000 other loud souls a rebound by the Cubs, leading Game Six 3-0 after seven innings. With one out and one on in the Marlins eighth, Luis Castillo lofted a fly ball that was coming right at Bartman. Doing what most anyone else would do with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to grab a free major league souvenir, Bartman instinctively reached with his glove right above the railing—and inadvertently stole the second out of the inning from Cubs left fielder Moises Alou, who angrily reacted by slamming his empty glove to the turf in disgust.

Fan interference was not called since Alou was reaching in past the railing, but Bartman knew not only the impact of what he had done, but how angry and crazy Cubs fans could get. Bartman prayed the Cubs would get out of the inning.

Eight Florida runs later, they did.

Given new life, Castillo walked. Ivan Rodriguez singled. Twenty-year-old prodigy Miguel Cabrera hit a grounder that looked ready to be turned into a force, if not an inning-ending double play—but Chicago shortstop Alex Gonzalez botched the pick-up. The error was just as critical for opening the Florida floodgates as Bartman’s glove, but few people will remember Gonzalez and opt to brood over poor Bartman, who had to be escorted away under heavy ballpark security, was hidden under the rafters for his own safety until well after the game was over, and was said to be so devastated over the event that even Commissioner Bud Selig called him a few days later to cheer him up, if that was possible.

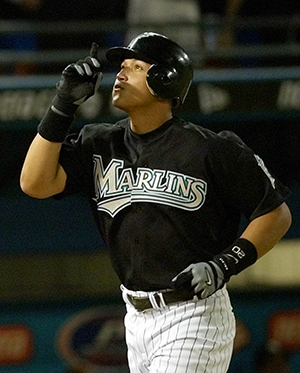

Moments after nearly getting beaned by an up-and-in Roger Clemens fastball, 20-year-old Florida rookie Miguel Cabrera launched a two-run, first-inning home run in Game Four of the World Series; the Marlins would win the game in 12 innings and take the next two contests to clinch the world title. (Associated Press)

For Dusty Baker, it was a remarkably haunting case of déjà vu, defeated in the postseason for the second straight year after holding a comfortable lead late in the potential series clincher.

The Marlins’ spunky resiliency carried on against the heavily favored Yankees in the World Series. They trailed two games to one and, in Game Four at Miami, threatened to fall further when a furious ninth-inning New York rally sent the game into extra innings. But in the bottom of the 12th, the Marlins sent up Alex Gonzalez—no relation to the Cubs namesake of the critical Game Six NLCS error—and, bursting out of a 5-for-53 slump, lined a walk-off homer off Yankees reliever Jeff Weaver for a 4-3 win and a firm momentum shift in Florida’s favor.

BTW: It was Weaver’s first appearance for the Yankees in a month.

After taking Game Five, 6-4, to move the series back to New York, the Marlins took what was considered a calculated risk and sent to the mound red-hot pitcher Josh Beckett on three days’ rest. Some opined it was better for manager Jack McKeon to give a more rested Beckett the ball for Game Seven if it was necessary, but McKeon sensed a big-game appetite from his young stopper and let him go at the Yankees.

Go at them Beckett did, throwing his fastball with stunning, consistent velocity at over 95 miles per hour. In 48 regular season starts through 2003, Beckett had not thrown a shutout, but with his five-hit blanking of the Yankees to gave the Marlins their second improbable championship in seven years, he had thrown his second of the 2003 postseason.

BTW: The Marlins became the first World Series champion since the 1914 Boston Braves to have been as much as 10 games under .500 during the regular season.

And so the curses lived on, prosperous as ever, taking new victims with them. Grady Little figured he’d be fired for leaving Pedro Martinez in two batters too long. He was right. In Chicago, the ball Steve Bartman muffed was auctioned off to a restaurant group in the name of the late Cubs broadcaster Harry Caray for exactly $113,824.16. The goal: To blow up the ball in the hopes that the curse of the Cubs might finally be lifted.

End the curse? Retire the mystique? Ruin all that you’ve become over a century of legendary anguish?

Then what?

The Boston Red Sox, for one, would soon find out.

Forward to 2004: Four Score and Six Years Hence Down 3-0 in the ALCS, the Boston Red Sox burst to life and spectacularly exorcise the Curse of the Bambino.

Forward to 2004: Four Score and Six Years Hence Down 3-0 in the ALCS, the Boston Red Sox burst to life and spectacularly exorcise the Curse of the Bambino.

Back to 2002: The Wild, Wild Card West The red-hot Anaheim Angels—riding high on the back of their Rally Monkey—attempt to overcome Barry Bonds and the San Francisco Giants.

Back to 2002: The Wild, Wild Card West The red-hot Anaheim Angels—riding high on the back of their Rally Monkey—attempt to overcome Barry Bonds and the San Francisco Giants.

2003 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2003 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2003 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2003 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.