THE YEARLY READER

2004: Four Score and Six Years Hence

Down three games to none in the ALCS against the archrival New York Yankees, the Boston Red Sox launch themselves on an unprecedented comeback that erases nearly a century of cursed frustration.

Dave Roberts’ ninth-inning steal—and his ensuing run that tied the New York Yankees in Game Four of the ALCS—was initially considered nothing more than a measure of respect for a Boston Red Sox team simply trying to avoid a sweep. It instead became the spark that ignited a remarkable—and unprecedented—comeback.

It was a turning point worthy of the most implausible Popeye episode. There were the Boston Red Sox, playing the role of the Sailor Man, weakened, bruised and beaten to the absolute edge of extinction by the New York Yankees, portraying Brutus—the belligerent adversary who earlier had stolen away the Olive Oyl within the cast: Superstar Alex Rodriguez.

Never in baseball history had a team come back to win a postseason series after falling behind three games to nothing. Worse for the Red Sox, they trailed in the ninth inning of ALCS Game Four, facing a virtual automatic in Yankees closer Mariano Rivera.

Brutus never looked to have it so easy.

Who knew if and where the Red Sox would get a hold of the proverbial spinach. Maybe it would come in the form of the ritual pre-game shots of Jack Daniels, or a wake-up slap in the face from the crisp New England fall weather, or maybe it would just be a sudden, volcanic release of 86 years’ worth of frustration.

But the jolt of fighting life would be delivered, and it electrified the Red Sox—igniting them on an incredible comeback that never dimmed until the season was over. It all capped a calendar year in which the team’s highs and lows continually made national sports headlines.

Tormented by their tough seven-game ALCS loss to the Yankees in 2003, the Red Sox engaged in a fierce offseason battle of talent build-up with other American League East rivals that dwarfed all other wintertime free agent activity taking place in baseball. Boston had already signed closer Keith Foulke, was about to snare tenacious pitcher Curt Schilling away from Arizona, and set its eyes on the winter’s grand prize: Alex Rodriguez.

The all-world shortstop was as frustrated trying to win in Texas as the modestly budgeted Rangers were frustrated trying to build a solid roster around his annual $25 million salary. So Rodriguez and the Rangers mutually agreed to part, and the Red Sox quickly stormed in to make a deal. By Christmas, they thought they had one, ready to ship troublesome star slugger Manny Ramirez to Texas in exchange for Rodriguez—who was willing to reduce his unmatched wages to play for a contender. The problem was, the powerful players’ union wasn’t willing to accept the pay dive as precedent and nixed the deal. The Red Sox, wincing at the thought of paying Rodriguez’s current salary, folded away from negotiations.

As it always had been since 1918, the Red Sox’ loss became the Yankees’ gain.

New York owner George Steinbrenner had continually proved that no player was too expensive to fit into Yankee pinstripes. The team had already ballooned its budget by acquiring stars in pitcher Kevin Brown and outfielder Gary Sheffield, and even though it had future Hall of Famer Derek Jeter situated at shortstop, that didn’t deter it from pursuing Rodriguez in the wake of the Red Sox’ failed attempt. Within weeks, the Yankees successfully completed their own deal for Rodriguez, who kept his current salary, moved to third base to accommodate Jeter, and gave the Yankees a roster with all-star value at virtually every position—all at a payroll cost approaching a whopping $200 million, nearly twice that of the next highest team: The Red Sox.

BTW: The Rangers, who received talented second baseman Alfonso Soriano in the trade, agreed to annually pay the Yankees $7 million of Rodriguez’s salary for the balance of his contract.

As the 800-pound Yankee gorilla grew larger, there were other problems just as prominent—and more internal—in Fenway Park. Manny Ramirez felt unwanted not only in the wake of the collapsed Rodriguez deal, but also after the Red Sox had placed him and his $20 million salary on waivers (there were no takers). And the Rodriguez plot also rubbed wrong on incumbent all-star shortstop Nomar Garciaparra, who sensed his days in Boston were numbered even after Rodriguez became a Yankee.

Piloted on the field by mild-mannered, first-year manager Terry Francona, the Red Sox progressed through the 2004 season once again playing second fiddle to the Yankees. Trailing New York by as much as 10 games, the Red Sox’ inconsistent play—punctuated by bad defense—prompted 30-year-old Boston general manager Theo Epstein to publicly avow a “change for change’s sake.” That came at the end of July when Garciaparra was packaged off to the Chicago Cubs as part of a trade involving four teams that netted Boston three borderline position starters (shortstop Orlando Cabrera, first baseman Doug Mientkiewicz and speedy outfielder Dave Roberts) who would play pivotal roles down the stretch.

But it was a game played the week before at Fenway that provided a rallying cry in the Red Sox clubhouse.

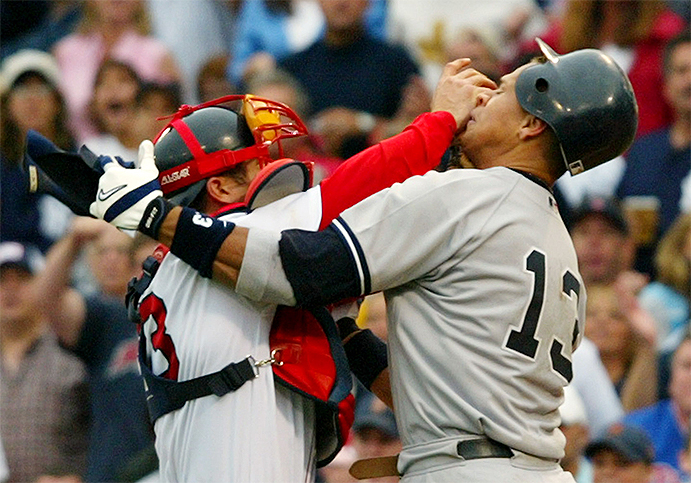

Boston catcher (and team captain) Jason Varitek sticks it to Alex Rodriguez during a July game at Fenway Park, after Rodriguez yelled at Red Sox pitcher Bronson Arroyo for hitting him. Six months earlier, Rodriguez appeared headed to Boston before the players’ union vetoed the trade. (Associated Press)

The Yankees came to town for a contest that Red Sox officials at first wanted to call off due to wet grounds, before Boston players talked them out of it. Playing on, the Red Sox trailed 3-0 in the third inning when Rodriguez, the shortstop who would be Boston’s, got tagged by a Bronson Arroyo pitch. Rodriguez profanely barked at Arroyo, prompting catcher Jason Varitek—to many, the heart and soul of the Red Sox—to get up and confront Rodriguez. When jawing nose-to-nose didn’t settle things, Varitek shoved his glove into Rodriguez’s face, igniting the annual Red Sox-Yankee brawl. Once emotions cooled, the Red Sox rallied to win, 11-10, when Bill Mueller drilled a two-run, walk-off homer in the ninth off Mariano Rivera.

On top of overcoming one of the game’s best closers, the added thrill of sticking it to Rodriguez thoroughly revived the Red Sox. Further enhanced by Garciaparra’s departure a week later, Boston fully focused on winning baseball and briefly nipped at the Yankees’ heels in the standings late in the year, but still settled for the AL wild card—their fourth in seven years.

The offense continued to be the Red Sox’ primary strength. The lineup was fueled at the top by Johnny Damon (.304 batting average, 20 home runs and 94 runs batted in), whose new-look, shoulder-length hair and lumberjack beard evoked wide-ranging comparisons from Jesus to Trog. Damon often scored courtesy of Ramirez and first baseman David Ortiz, whose bulky frame was reminiscent of recent Boston boomer Mo Vaughn.

BTW: Both Ramirez and Ortiz finished the year clearing .300 with 40 homers and 130 RBIs, the first pair of teammates to do so since Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

As the season turned to September, the Yankees engaged in a rash of dubious moments as if eagerly trying to hand Boston the AL East title on a silver platter. New York suffered its worst loss ever—at home, no less, 22-0 to the Cleveland Indians—and Steinbrenner got into trouble when he compared the “tragedy” of the blowout loss to the 9-11 terrorist attacks in an attempt to rally the organization. A trade for pitcher Esteban Loaiza proved disastrous when the sudden 20-game winner of 2003 bombed on the Yankee mound and got demoted to the bullpen. Kevin Brown, hardly a one-year wonder by contrast, foolishly took on a clubhouse wall—and lost, breaking his hand—after a rough outing against Baltimore. And when the lowly Tampa Bay Devil Rays failed to show up at Yankee Stadium for the first game of a day-night doubleheader—because players and coaches had to cope with the latest in a series of powerful hurricanes to sock Florida—the Yankees demanded a forfeit. Commissioner Bud Selig denied the request, and the zealous New York media grilled the Yankees, accusing the team of insensitivity—to say nothing of desperately seeking wins any way it could.

BTW: Loaiza, a journeyman starter who was 21-9 for the Chicago White Sox in 2003, was 1-2 with an 8.50 ERA in 10 appearances with New York…The Yankees went on to sweep the Devil Rays in the four-game series at Yankee Stadium that began with the Rays showing up late.

That AL East is a Beast

All-Star reliever Mariano Rivera had no problem closing down opponents throughout the 2004 regular season—as long as they represented someone outside of the AL East. Boston, Baltimore, Toronto and Tampa Bay all combined to make Rivera far more mortal than the rest of the majors.

Despite all of the on- and off-field distractions, the remarkable assortment of talent and experience on the Yankee roster gave the team a resiliency that resulted in a major league record 61 come-from-behind wins. And once the Yankees took the lead, they seldom relinquished it; they were 88-2 when ahead after eight innings.

The two losses were to the Red Sox.

The news of the offseason, preseason and regular season had pretty much revolved around the Yankees and Red Sox, so it only seemed natural that they would take center stage for the postseason as well. The two teams easily survived first round playoff competition to pair up for the second straight year in the ALCS. And over that series’ first three-plus games, the Yankees, with Rodriguez, all but rendered the Red Sox—without Rodriguez—irrelevant.

New York zoomed to an 8-0 lead in Game One before triumphing, 10-7; beat ace Pedro Martinez in Game Two, 3-1; and demolished the Red Sox at Fenway in Game Three, setting an LCS record for runs scored in a 19-8 rout. The Red Sox made a game of it in Game Four but still trailed, 4-3, going to the bottom of the ninth. Three outs away from being swept, the Red Sox could hear a pin drop at Fenway Park. Red Sox Nation looked stone-faced, cold, indifferent. Even if Boston could avoid the sweep, so what? No team in baseball history had ever won a series after trailing three games to none. Twenty-five previous teams tried and failed. Same thing in the NBA, 75 times. Two NHL teams did manage to overcome 3-0—but 136 others could not.

The Red Sox looked at the situation like base campers staring up at Mount Everest. Maybe you can conquer it, but it must be done one step at a time. So the Red Sox embarked. Dave Roberts crucially kick-started Boston with a stolen base that led to a game-tying run off Mariano Rivera in the ninth; three innings later, David Ortiz won it with a homer. The next night in Game Five, Ortiz again erased a late Yankees lead and sent the game into overtime, where two exhaustive bullpens somehow traded blanks through the 14th until Ortiz, once more, punched out a single to score Damon and end a six-hour marathon to send the series back to New York.

After a peculiar pre-Game Six bonding in which Boston players took sips of Jack Daniels from a paper cup, the Red Sox rose to the moment behind starter Curt Schilling—owner of a 21-6 regular season mark who, despite pitching on a bruised, bloody ankle, threw brilliantly to help steer the Red Sox to a 4-2 win and even the series. Aiding the Red Sox were the umpires, who rightfully reversed two pivotal calls in Boston’s favor—including a three-run Mark Bellhorn home run initially called a double after the ball bounced off a fan above the wall, and not the wall itself.

Just forcing a seventh game after trailing 3-0 was unprecedented in baseball annals, so both teams faced uncharted territory for the winner-take-ALCS at New York. Such fear of the unknown was hardly going to faze the Red Sox, whose momentum was just beginning to kick into high gear.

From the very start of Game Seven, it was obvious that the Red Sox had destiny clenched within their fists. Ortiz smashed a two-run shot off Kevin Brown in the first. An inning later, the beleaguered Brown was removed and the first pitch thrown by his replacement, Javier Vazquez, was powered well over the right-field wall for a grand slam by Damon—who until that moment was having an awful series. When Damon homered again off Vazquez in the fourth to make it 8-1—a lead that stingy Boston starter Derek Lowe would easily hold—it became the Yankee fans’ turn to look stone-faced, cold, indifferent.

BTW: Lowe would allow just a run on a hit and a walk through six innings in Game Seven, won by Boston, 10-3.

It Ain’t Easy Being Down Three-Zip

Until the Red Sox’ remarkable revival in the 2004 ALCS, no major league team had ever come back to win a best-of-seven postseason series after losing its first three games. In fact, a vast majority of teams quickly collapsed under the weight of the burden and couldn’t even squeeze out a single victory before being handed a fourth and final loss.

When Popeye regains his strength, Brutus stands no chance to regain his. And neither would the Yankees, who after going three up were given the four-and-out boot by the Red Sox.

The consolation for the Yankees: They still had Olive Oyl, and a chance to fight another day.

Having achieved the impossible, the Red Sox had an even tougher task ahead of them: Exercising the Curse. To do so meant overcoming the powerful St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series.

Dominating the competitive National League’s Central Division, the Cardinals exhibited a virtual Murderer’s Row of sluggers led by Albert Pujols (.331 average, 46 homers and 123 RBIs), Jim Edmonds (.301, 42, 111) and Scott Rolen (.314, 34, 124); the lineup was further enhanced late in the year with the acquisition from Colorado of Larry Walker (11 homers and 27 RBIs in 44 games for St. Louis). The team’s vaunted hitting hogged the headlines from its relative no-name cast of competent (if not sterling) starting pitching, which featured three 15-game winners (Chris Carpenter, Jason Marquis and Matt Morris) and a 16-game winner (Jeff Suppan).

After dispensing of the NL West-winning Los Angeles Dodgers in the first round of the playoffs, the Cardinals matched up with a red-hot NLCS opponent in the Houston Astros, who steamrolled their way into the postseason as the NL wild card, gave the Atlanta Braves their obligatory first-round exit—and readied to face St. Louis as the only NL team that won its regular season series (10-8) against the high-flying Cardinals.

The feisty Astros threw everything they could at the Cardinals. Roger Clemens, unretired and tough as ever, grounded St. Louis in Game Four. Unheralded pitcher Brandon Backe—322 career wins behind Clemens— threw eight shutout innings in Game Five, allowing just a hit and two walks. Young closer Brad Ridge was all but untouchable. And on offense, the Astros got a one-man show from center fielder Carlos Beltran, a midseason pick-up who escaped obscurity in Kansas City and basked in the long-overdue glow of the spotlight with a sensational performance.

BTW: Beltran’s NLCS numbers included a .412 batting average, 12 runs, four home runs, four steals and a number of spectacular catches in the outfield.

All this, and Houston fell short. Home field advantage came in handy for the Cardinals, who overcame three losses at Houston by winning all four games played at St. Louis—including an assertive Game Seven effort in which the Cardinals outlasted Clemens and kept Beltran hitless.

The Boston Red Sox were hardly perfect in the first two games of the World Series against St. Louis at Fenway Park, committing four errors in each game. But destiny has a way of overcoming such travails, and the Red Sox won both contests, 11-9 and 6-2.

The Cardinals got no such serendipity from their own miscues when they returned home for Game Three. Against Pedro Martinez, the Cardinals ran themselves out of a first-inning rally when Larry Walker was gunned down at the plate on an unexpectedly good throw from left fielder Manny Ramirez. Two innings later, the Cardinals truly shot themselves in the foot when, with runners on second and third and no one out, starting pitcher Jeff Suppan—the lead runner on third—inexplicably held up on a Walker grounder to the right side of the infield, and got himself trapped between bases when the Red Sox took note. Initially happy to concede the run, the Red Sox were even happier to trap and tag Suppan and kill another Cardinal rally—and with it, just about any realistic chances that St. Louis could rebound.

Martinez settled in and sailed into the eighth inning of Game Three, notched by Boston, 4-1. Then it was Derek Lowe’s turn in Game Four. The Red Sox pitcher who iced the ALCS against the Yankees continued to throw on target for what would be the World Series clincher, tossing seven shutout innings and letting the bullpen take it from there for a 3-0 victory.

BTW: The victories by Martinez and Lowe would be their last in a Boston uniform; Martinez signed with the Mets for 2005, Lowe with the Dodgers.

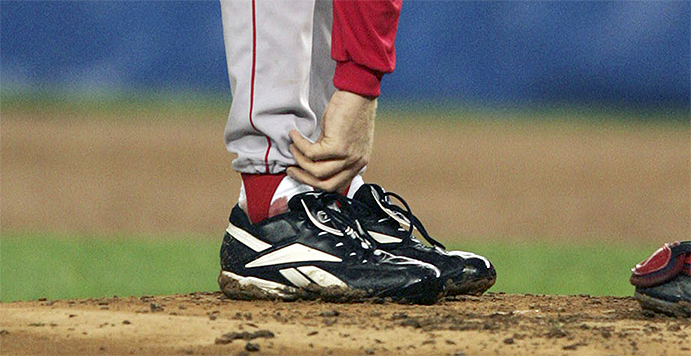

Curt Schilling’s bloody sock became the stuff of legends after successive strong postseason outings from the Boston pitcher that greatly benefitted the Red Sox. The blood came courtesy of loosened sutures following a procedure on his ankle. (Associated Press)

Red Sox addicts across the nation didn’t know what to do with themselves. For them, the concept of their beloved winning a World Series was alien, unless they were old enough to remember 1918. But party they would, dancing away “The Curse” that had held their psyches hostage for generations.

It was a long, historically painful wait. The longer The Curse lasted, the more desperate the measures to end it. Whatever it took—spinach, Jack Daniels—anything to wipe 86 years of affliction away from the Red Sox and their nation.

And for once, it worked.

Forward to 2005: At the End of the Primrose Path After years of looking the other way, baseball is publicaly forced to confront its dirty steroid laundry.

Forward to 2005: At the End of the Primrose Path After years of looking the other way, baseball is publicaly forced to confront its dirty steroid laundry.

Back to 2003: Curses, Inc. Baseball’s two most famously cursed—the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox—add to their long-suffering legend of heartbreak.

Back to 2003: Curses, Inc. Baseball’s two most famously cursed—the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox—add to their long-suffering legend of heartbreak.

2004 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2004 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2004 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2004 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The two-time All-Star reflects on a 15-year career, his wonderful 2004 season, and his recounting of an interesting trade (actually, trades) involving catcher Doug Mirabelli.

The two-time All-Star reflects on a 15-year career, his wonderful 2004 season, and his recounting of an interesting trade (actually, trades) involving catcher Doug Mirabelli.