The Ballparks

Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium

Atlanta, Georgia

(Flickr—Photoscream)

Strategically placed south of downtown near the nexus of three major Interstates, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium ran hot and cold—and sometimes just plain weird, given the promotional lunacy born out of Ted Turner’s early years running the Braves. But the modern venue, efficiently propped up with staggering speed, catapulted the Peach City from overgrown drudgery into the big leagues, helping to cement its standing as the Hub of the New South.

Not so long ago, this writer along with a good friend were both headed back to our hotel in Atlanta after a day of business. Our drive took us southward on a busy freeway shared by two Interstates (75 and 85) that I knew would pass right by Turner Field, at the time the Atlanta Braves’ home ballpark. I asked my friend if we could stop and check it out. He nodded with all the energy of a bored dental patient; his passion for baseball died ages ago, when the Giants traded Willie Mays.

We pulled into an expansive, empty parking lot north of Turner Field, past a security guard who was content to waive us through. My friend was more interested in checking his messages than Turner Field, so he stayed in the car. I got out, walked the exterior, took some photos and came back. Once I returned, I noticed something sticking out at the back of the parking lot. We decided to investigate, and instantly I recalled: It was the remnant of the left-field fence from Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the only physical asset still left standing from the old venue. Its historical value: It’s the section of the fence cleared by Hank Aaron with his record-setting 715th home run in 1974. When my friend caught on to it, his passion re-awoke. He had no idea through all this time that he had been hanging out on what was, from his perspective, hallowed baseball grounds. The exact location of the stadium’s former playing field was now replicated in paint on the parking lot pavement. We got out and played pitcher and batter—sans ball, bat and glove, but not imagination.

Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was a serviceable, dignified and unremarkable stadium, but it was not void of remarkable moments. Aaron’s 715th certainly ranks at the top. Not far behind were the streaky 1982 Braves. And of course, there was the team’s shocking, out-of-nowhere rise in the early 1990s to help close out the stadium on a high. These moments give Atlantans enough positive weight to cancel out the bad times that permeated through much of the stadium’s existence, as the Braves lost more than they won and struggled to click the turnstiles despite outrageous promotions such as Wet T-Shirt Night. The stadium’s co-tenants, football’s Falcons, were even less successful—compiling only six winning records and no Super Bowl appearances in 26 seasons. Their penchant for failure was best remembered in 1973 when running back Dave Hampton surpassed the magical 1,000-yard mark in the final minutes of the season’s last game, prompting a brief stoppage for team officials to celebrate—and before he lost five yards on the next carry to negate the whole achievement.

The presence of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was crucial to a city that needed a link from more humble, segregationist times to the modern Mecca of the South that it is today. It’s quite possible that without the stadium, Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport would not be one of the world’s busiest, CNN would not have been born and the 1996 Summer Olympics—which helped hasten the end of the stadium—might never have come to town.

Ivan the Wonderful.

For decades, talk of building a top-line sports facility in Atlanta was just that: Talk. The best the city could vouch for in terms of pro sports was the minor league Atlanta Crackers, whose popularity peaked in the immediate postwar years, once drawing as many as 400,000 fans. It was a telltale sign that Atlanta could support a major league team; the problem was, any major league would be loath to support a team in a city and state that still separated blacks from whites. It ultimately doomed the Crackers, whose momentum was snuffed out in the dying (and whites-only) Southern Association, as well as a chance for Atlanta to become a charter member of the American Football League in 1960, edged out as an eighth franchise by Oakland.

Racial policy didn’t hold back local dreamers who set about trying to build a much larger, more modern stadium as opposed to aging Ponce De Leon Park, the longtime home of the Crackers. In the late 1950s, as Atlanta began to become more prominently mentioned as a landing spot for a relocated or expanded major league franchise, there were a handful of stadium proposals, all of which died almost as soon as they were born—including a $10 million facility seating up to 75,000 in neighboring Cobb County, where the Braves would eventually wind up 60 years later.

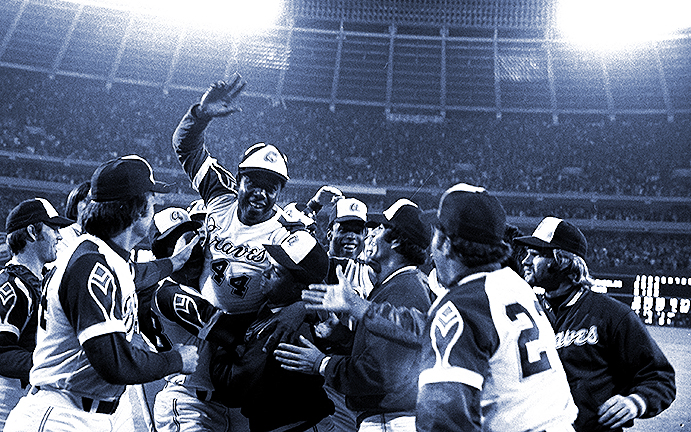

Hank Aaron celebrates his 715th home run to surpass Babe Ruth’s all-time mark early in 1974. The game drew the largest baseball crowd in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium history. (Associated Press)

The new stadium movement finally received legitimate traction when Ivan Allen Jr., a prominent local business leader who headed the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, threw his hat into the 1961 mayoral race with the pledge that, if elected, he’d build a stadium—and, oh, he’d desegregate the city. Pro-business folks liked the former idea. Atlanta’s black residents, making up nearly half of the city population, liked the latter.

Allen won, and the stadium wheels went into motion. The newly formed Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority looked at optimal, available spaces of land, while Allen shook the local trees seeking financial and business support for the new venue. He got the financial end of matters taken care of through good friend Mills Lane, who just happened to be the president of C&S Bank, the South’s largest. From the business side came Arthur Montgomery, a top exec at Atlanta-based Coca-Cola whose job it was to lobby bigwigs from both baseball and the National Football League to land a team in a new stadium. Expansion was an active proposition for the NFL, but with four new baseball teams having just been rewarded in the majors, Montgomery was going to have to whet the appetites of any existing owners unsatisfied with their current situation.

Montgomery found one disgruntled lord in Charles Finley, who had bought the Kansas City A’s a few years earlier and immediately let it be known that he’d rather be anywhere but Kansas City. Finley quietly visited Atlanta in a shroud of secrecy—even the city’s two newspapers kept a lid on his presence as they were actively behind the effort to lure pro sports to the area—and checked out the four stadium sites narrowed down by the Recreation Authority. He became ecstatic when shown one of them, an area just south of downtown just a few tape-measure shots away from a nexus of three recently constructed interstate freeways (20, 75 and 85) that could ferry fans in from just about anywhere. The Atlanta A’s appeared to be reality until the other American League owners had their say and, fearing legal retribution from Kansas City, said no to Finley.

Although the local movers and shakers were back at Square One in the hunt for a major league team, Finley’s love for the south of downtown site was in line with the Authority’s thinking. And it was theirs for the taking, because by then there wasn’t much left of the Summerhill neighborhood where Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium would eventually be placed. Summerhill was once a modest and multi-cultural middle-class community, pleasant enough to house the Governor’s Mansion. But it suffered like most American inner-city areas after World War II; suburban flight first weakened the neighborhood, before being virtually destroyed by the building of the Interstates—with up to 4,000 households obliterated. The site desired by the Authority was already cleared for urban renewal, so there were few people left to chase away and make room for a stadium.

Hurry Up and Wait.

With the A’s out of the Atlanta picture, Arthur Montgomery put down his Coke and went back to nosing about the major league landscape to find another interested party. It just so happened he had a conduit to the ownership group for the Milwaukee Braves, who just a decade earlier were the darlings of baseball by moving from Boston and filling up newly constructed County Stadium with annual attendance figures of two million, something previously unheard of. Those days were suddenly long gone; the gate had sunk back under a million and the team was sold to new ownership that wasn’t keen on staying in Milwaukee. Montgomery quieted huddled with the Braves and told them, if you want Atlanta, it’s yours. Without hesitation, the Braves agreed.

Fueled by the Braves’ commitment, Mayor Allen quickly sought approval for the stadium, teasing the locals and baseball pundits by announcing that “a” team was headed to Atlanta—he just wouldn’t say who. On March 6, 1964, the Recreational Authority voted to move forward with the stadium in front of an audience of nearly 500 that yielded nary a dissenting voice. John White, who chaired the Authority’s finance committee, was astonished. “In all my years as an alderman,” he told The Sporting News, “this is the first time I never saw a single vote against something.”

Allen got his team and stadium approval; now all he needed was time. That he didn’t have much of. The Braves insisted on beginning their Atlanta tenure in 1965, giving Allen a short 11 months to build the stadium from scratch. Fortunately, there was an architect nearby with a solution.

Heery & Heery, established in 1952, was an Atlanta-based firm that had grown experienced enough to understand, by the early 1960s, that something was terribly amiss within their industry. That something was management. With so many moving parts involved in the building process, from architects to planners to all the various construction contractors, there seemed a lack of synchronization that could easily speed a project up without sacrificing quality control. So Heery & Heery established a management protocol that helped streamline the process and keep it ahead of schedule. This was music to Allen’s ears; after initially looking at another firm, Finch, Alexander, Barnes, Rothschild, and Paschal (or FABRAP to the short attention spans among us), he decided to go hybrid and bring Heery & Heery in to partner on the stadium project. There was no time for inter-agency ego bruising upon one another, and fortunately that would become moot as the two firms got along harmoniously and began a partnership that led to other projects, including Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium a few years later.

Part of what kept Heery & Heery and FABRAP in lockstep was their sharing of the same design philosophy. They both embraced a modern, quasi-minimalist “international style,” based on Bauhaus principles that prioritized function over form, certainly over décor. Shunning traditional Southern aesthetics, Atlanta Stadium (as it was first called) was like many of the other multi-purpose stadia that would be built in the 1960s—contemporary but sterile, practical but domesticated, bureaucratically formed to appease both football and baseball sensitivities within the same space.

Though completely enclosed, Atlanta Stadium breathed to the outside with outer concourses exposed through a series of beams 20 feet apart than leaned inward and held up the upper-level structure. More openness could be found at the top of the upper deck as airy slats revealed the surrounding environs for those sitting in the very top row, should the activities on the field become bereft of any action. Sky blue hues echoed throughout the otherwise whitened stadium, from the 50,000-plus wooden seats across three decks (including a petite second level partly reserved for media) to its upper-deck overhang, rimmed with horizontal lighting banks rather than the tall towers of electric lamps used at older facilities.

The Heery/FABRAP amalgam impressively accomplished its mission by getting Atlanta Stadium virtually completed on time and ready for Opening Day 1965. Not ready, though, were the Braves. Nine months earlier, Mayor Allen’s closely guarded secret had leaked out, revealing to the public that, indeed, it was the Braves who were on the move to Atlanta. Milwaukee officials hardly sat quiet, aggressively bursting into legal mode and suing the Braves into staying; they got a partial victory by forcing the team to stay through 1965 and honor the remainder of their lease with County Stadium. Beyond that, it had to argue a violation of antitrust laws to keep the Braves bound to Wisconsin, but that became a much tougher sell—one that nevertheless got within earshot of the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to discuss.

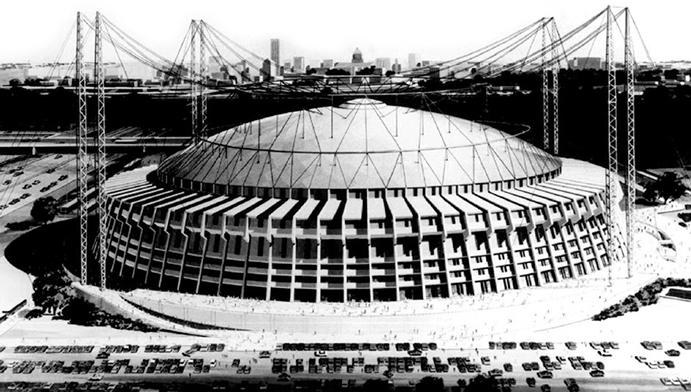

An artist’s conception of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium with a plastic retractable roof, which was under consideration (but never built) shortly after the venue’s opening.

With the Braves chained to Milwaukee for one more year, that left Atlanta Stadium’s inaugural 1965 baseball campaign to be hosted by none other than the Atlanta Crackers, an integrated Triple-A version of the older, whites-only ballclub of lore. But Milwaukee couldn’t keep the Braves from christening the stadium with a series of three preseason exhibitions against the Detroit Tigers. The stadium’s soft opening was preceded by a soft parade with 100,000 Atlantans welcoming their team of the near future; the three games that followed drew a total of 106,000 fans—not far off from the 169,000 the Crackers would attract to Atlanta Stadium for the entire 1965 season, a count about half that of what was expected.

An “A” for Effort, Atlanta—and Aaron.

Better late than never, the Braves arrived from their forced lame duck session in Milwaukee and much bigger crowds arrived with them, as 1,539,000 fans spun through the turnstiles at Atlanta Stadium in 1966. Amid the modern venue’s tedium was one bit of kitsch: Big Victor, a giant Indian sculpture made of Styrofoam that rose high behind the right-field fence. The big fellow sat inert until a Braves player belted a home run, from which it would waive its right arm holding a hatchet, while its eyes rolled upward as if watching a deep drive soar over its head. Big Vic didn’t last long, barely a year—rain and the multiple dings from taking direct hits from home run balls caused numerous mechanical issues—but it certainly was busy during the Braves’ first year as the team drilled 119 home runs at home; the total of 201 was the most among National League ballparks. It set a trend in which Atlanta Stadium would be tops for six of its first eight years of major league operation in homers, earning a nickname that would stick: The Launching Pad.

There were three primary factors that accounted for the stadium’s power surge. First, its elevation of 1,057 feet that was the majors’ highest until mile-high Colorado came along in 1993. Second, hitters enjoyed somewhat comfortable field dimensions, with a 330-foot distance down each line, 385 to the power alleys (it was 375 from 1969-73), and 400 to straightaway center.

The third factor was the presence of one Henry Louis Aaron.

Born 250 miles away from Atlanta in Mobile, Alabama, Aaron went through a harrowing ordeal as the first black ballplayer of the minor-league South Atlantic (“Sally”) League in the early 1950s, enduring racial abuse similar to what Jackie Robinson had to deal with during his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. A move to Milwaukee, a more racially benign region, made Aaron feel more at peace—and his prodigious numbers at the plate proved it. Returning to the Deep South was not terribly ideal for Aaron, but fans at Atlanta Stadium quickly embraced him as their star player. One thing was for sure; Aaron loved the new stadium and the offensive opportunity it provided him. And he took advantage, averaging 22 homers a year just at home through his first eight years in Atlanta. In 1970, Aaron belted one of only four home runs in stadium history to make its way into the upper deck; three years later, he joined Davey Johnson and Darrell Evans as the first trio of teammates to each hit 40 homers in the same season. Aaron’s career OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) at Atlanta Stadium was an astonishing .992.

Aaron’s milestone moments seemed exclusively reserved for Atlanta Stadium. He hit his 500th career home run in Atlanta. And his 600th. And his 700th. Finally, at the Braves’ 1974 home opener, with the weight of a captivated world upon his shoulders, Aaron blasted a pitch from the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Al Downing high above the outfield—painted with a giant American flag shaped in the lower 48 states—and over the wire fence in left field into the Atlanta bullpen for his 715th home run to pass Babe Ruth on the all-time list. Accomplished before 53,775—the largest baseball crowd ever at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium—Aaron’s record-breaker would become the stadium’s most memorable moment; catching the ball in the bullpen (and receiving $10,000 for it) was Braves reliever Tom House, sweetening his own AFCS resume that included a career 2.28 earned run average—the lowest by anyone throwing a minimum of 100 innings at the stadium.

A truly dignified man, Hank Aaron felt not only relief but a sense of amnesty with his historic home run. The years leading up to 715 had been torturous; his pursuit of Ruth, a fabled white man, rankled a virulent cache of bigots who crawled out from the underneath and wrote hate mail to Aaron, some of it laced with death threats. But after 715, they crawled back and never returned; Following his retirement, Aaron remained a citizen of Atlanta, evolving from hero to ambassador for the Braves and baseball in general. Without his presence, the early years of Atlanta Stadium likely would have been veiled in anonymity.

The exterior of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium during the 1970s. (Wikimedia—Jim Pickerell)

Dawn of the Ted.

Such indistinctness became painfully obvious when Aaron departed back to Milwaukee in 1975, finishing out his career as a designated hitter for the American League’s Brewers. Overnight, the Braves’ marquee value turned stale as they tanked in the standings and fans became disinterested. In the Braves’ first year A.A. (After Aaron), only 535,000 showed up for the entire season. A game late in the year drew a paltry 737 fans, the lowest crowd count in Atlanta Braves history.

The losing and lack of star power exposed a major flaw in AFCS’ location; though conveniently close to downtown and easily accessible to major freeways, most of the fans buying the tickets—the ones with the money—lived north of the I-285 loop, some 15 miles or more away in the affluent suburbs. For many of these folks, it wasn’t worth of it to inch their way through Atlanta’s notorious, insufferable traffic to watch a lifeless team. This didn’t just apply to the Braves; the Falcons felt it as well when only 10,000 fans showed up for their final home game in 1974. For the NFL, which now viewed 50,000 as the standard, this was highly embarrassing—but truth be told, this was a Falcons team with an embarrassing offense that averaged seven points a game.

The Braves’ ownership group, facing déjà vu all over again, decided that rather than look elsewhere as it did in Milwaukee, it sold the franchise. Buying it was one Ted Turner.

The brash, 37-year-old Turner was equal parts media magnate, champion yachtsman, sports entrepreneur and shameless promoter. He certainly made good use of the latter skill with the Braves. To make up for a lousy team, Turner took Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium—by now named as such after Fulton County squabbled about not getting any credit for its role in realizing the venue—and turned it into a funhouse with a series of promotions and gimmicks that would have made a minor league marketer blush. There was bathtub racing. And ostrich racing. And another race in which Turner himself beat out Philadelphia reliever Tug McGraw by rolling a ball around the bases with his nose. Most notoriously, the Braves under Turner held Wet T-Shirt Night, won by the daughter of a Methodist minister. Daddy, very likely, did not approve.

Baseball’s other owners, who took a step back at Turner’s sideshow shenanigans, strongly put their foot forward when it came to his attempts to meddle with the game. Turner was fined for tampering with San Francisco outfielder Gary Matthews before he became a free agent (he eventually got Matthews anyway), wanted to use pitcher Andy Messersmith as a billboard for his TV station WCTG by putting “Channel 17” on the back of his jersey (MLB said no) and put himself in the dugout as the Braves’ manager after giving Dave Bristol a leave of absence (MLB again said no, but only after Turner got away with it for one game).

Turner’s wacky pizzazz bumped up attendance a few notches at AFCS, but for the most part the suburbanites stayed home. Fact was, the Braves were just an awful team; the only players doing the launching at the Launching Pad were the visitors. It never got worse than on July 30, 1978, when the Montreal Expos came to town and hammered away at the Braves, 19-0 on a stadium-record 28 hits. Of those, eight went over the fence (another AFCS record)—with two hit in one inning by Andre Dawson, and three for the game from Larry Parrish, who two years later would record another hat trick in Atlanta. Somewhere, Big Victor was rolling his eyes all over again—this time, out of humiliation.

Reign and Cable.

Then came 1982. The Braves, with just one winning record over their previous seven seasons—that being an 81-80 mark in 1980—took baseball by storm by winning their first 13 games of the year to set a major league record. The timing was perfect; Turner had recently taken his local UHF station, gave it new network-ish call letters (WTBS) and put it—along with the Braves games it broadcast—on basic cable systems nationwide. As cable viewership mushroomed from the antenna-infested 1970s, the Braves and their sudden winning were exposed to viewers from Alaska to Florida and made legions of new fans; the WTBS “superstation,” milking the moment for all it was worth, began advertising the Braves as “America’s Team,” stealing from football’s Dallas Cowboys.

The home of Braves mascot Chief Noc-A-Homa was taken down late in successive seasons of 1982-83 to provide more seating—and in both cases, the Braves went into immediate funks. (Wikimedia—The Digital Library of Georgia)

Mystery repeated itself a year later when the Braves, again rolling along in first place before their first AFCS gate of over two million fans, evicted the Chief once more to free up the same seats. Sure enough, the losses piled up anew, and Atlanta’s 6.5-game lead dried up within two weeks. The fans, by now more weary of a curse than Turner, pled with him to bring the Chief back; a local TV station even offered to pay the cost of the additional 250 seats for every home game that remained so the teepee could stay, but this time Turner said no—perhaps because he didn’t want to grant free P.R. to a rival station. The Braves ended the season in second place, three games behind the Dodgers.

Knuckles and Muscle.

The early 1980s brought out the two most prolific Braves to star at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

The ageless Phil Niekro saw it all at AFCS as a member of the Braves, from their 1966 debut through 1983. He didn’t embrace the knuckleball that would turn him into a Hall-of-Fame ace until 1971, but once he did he not only confounded opponents and his own catchers with the pitch’s unpredictable movement, but historians who now look back upon his numbers and wonder: How? How did he amass over 300 innings four times? Start 44 games in one season? Win and lose 20 games each in the same year? Whether the Braves were good or bad, Atlanta fans could always depend on Niekro, and although he was just as victimized by the easy reaches of the Launching Pad’s outfield fences as anyone else, he also took advantage of the stadium’s foul territory, among the majors’ most spacious.

Niekro’s 130 wins at the stadium were nearly double that of the next guy on the list (Tom Glavine, with 70), and he loved pitching at the stadium so much that when the Braves released him at age 44, he felt like he was being booted out of his own home. Overall, the Braves were so thrilled with Niekro’s career effort that Turner quickly commissioned a statue of the pitcher’s likeness while he played on elsewhere; the finished product sat in storage for four years and was unveiled before he even retired, in 1987—the same year he finished his career with a symbolic one-and-done start for the Braves following his release from the Toronto Blue Jays.

Equaling Niekro in popularity—if not peculiarity—was Dale Murphy, the tall, mild-mannered Mormon slugger who reigned as one of the NL’s top stars of the 1980s. He was especially dangerous from 1982-87, batting .310 with prodigious power at AFCS. Nobody played more games (960) and accumulated more runs (589), hits (991), home runs (205) and RBIs (603) at the stadium than Murphy, who won back-to-back NL MVP awards in 1982-83 and appeared in seven All-Star Games as a member of the Braves.

Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, during perhaps the craziest game ever played there: A 19-inning affair with the Mets (who won, 16-13) on the Fourth—and Fifth—of July, 1985. (Flickr-RJCox)

Crazy Eighties.

Murphy provided the perfect counterweight to balance the even from the odd at AFCS during the 1980s. The Braves’ Dion James, in 1987, hit a fly ball that struck and killed a dove. Bob Horner, Murphy’s slugging sidekick, launched four home runs in a 1986 game—and the Braves still lost. In 1983, eccentric Braves pitcher Pascual Perez missed a start at the stadium when he couldn’t find it, hopelessly driving in circles on the I-285 loop for three hours before figuring things out a few innings too late. A year later, Perez did make it on time for a start against San Diego and proceeded to be the prime target of a particularly nasty beanball war that erupted between the Padres and Braves, leading to the ejection of 15 players, both managers and even two fans.

But the craziest collection of action ever witnessed at Atlanta-Fulton took place in 1985 on the Fourth—and Fifth—of July, when the Braves and New York Mets hooked up for a rain-delayed, ejection-filled 19-inning affair that seemed to go on forever. WTBS viewers thinking they were catching a replay of the game soon realized they were watching it live, and they likely remained glued to the set—so long as they could stay awake—as one wacky moment after enough kept the game knotted up until it mercifully ended at 4:00 in the morning, allowing the Braves to finally shoot off a planned fireworks display for a fraction of the 44,000 who stayed through it all. Unfortunately, the bombs bursting in air startled nearby residents out of their sleep, with some believing that the neighborhood was under attack. It prompted the city to pass a new law banning fireworks after midnight.

In the late 1980s, the Braves bottomed out again in the standings and Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium once more became a ghost town. America’s Team? The rest of America could have it, thought many in Atlanta. From 1988-90, the Braves failed to exceed one million in attendance, a shameful circumstance given that two million had become the majors’ new normal. An annual motocross event, usually held before Opening Day, made an already atrocious field even worse. Fixing it up wasn’t something the Braves could count on; whereas most other ballparks hired professional groundskeepers, AFCS’ mix of Bermuda grass and Red Georgia clay dirt was looked after by city maintenance workers. Result: Bad field. The Sporting News’ Bill Conlin once remarked that the stadium’s playing surface “looks as though it had just been victimized by Sherman’s march to the center-field fence.”

In 1988, the Braves publicly began to tire of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. They asked the city to consider a downtown baseball-only facility that could be ready by 1996, or they would threaten a move to the ‘burbs and neighboring Gwinnett County, where leaders there were dreaming up a $55 million yard with 45,000 seats.

The only remnant of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium left standing after its demolition was a segment of the outfield wall cleared by Hank Aaron for his 715th career home run. It sat in the parking lot of Turner Field.

Saving the Best for Last.

Just when everything appeared to hit rock bottom, the totally unexpected occurred. The Braves got good. Very good. A rotation featuring top prospects Tom Glavine, Steve Avery and John Smoltz finally saw the light. Young slugger David Justice developed into an offensive star. Veteran infielder Terry Pendleton came in and provided critical sage. And there was outfielder Deion Sanders, the fleet braggadocio who not only starred for the Braves but also for the Falcons, picking off passes and returning punts for touchdowns on Sunday at AFCS before returning to stealing bases during the week. After a fair start to 1991, the Braves stormed through the season’s second half to take the NL West and, for the first time in Atlanta, the NL flag by upending Pittsburgh in seven games. The goal of a worst-to-first championship fell painfully short in Game Seven of the World Series when Smoltz conceded a tense, 10-inning duel to the Minnesota Twins and pitcher Jack Morris.

Unlike the 1982 Braves that also came out of nowhere, the 1991 edition proved to be no one-and-done mirage. The Braves only got better as the decade wore on, as the young stars evolved and more talent came on board with incomparable ace Greg Maddux and smooth switch-hitting third baseman Chipper Jones. This was something the fans were not going to stay at home and ignore; attendance at AFCS leapfrogged from 980,000 in 1990 to 2.1 million in 1991, to over three million in 1992, to a stunning 3,884,725 in 1993—setting a (still existing) franchise record by nearly selling out every game. For the first time, spectators became part of the show by performing the Tomahawk Chop, a trance-like arm extension (imitating a hatchet throw in slow motion) and vocal chant borrowed from Florida State University that would become a staple at Braves games. One fan took the Tomahawk Chop a bit too literally after Atlanta clinched the NL West in 1991, chopping off the bronze bat from the Hank Aaron sculpture outside the stadium’s gates.

If the news on the field wasn’t sweet enough for the Braves, it was even sweeter off the field. With the surprise announcement that Atlanta had beaten out Athens (Greece, not Georgia) to host the 1996 Summer Olympics came word that the main venue to be constructed for the Games, right across the street from AFCS, would be converted into a new Braves ballpark the following year. This helped soften the Braves’ stress of looking for a new place and let them embrace the finite remainder of their tenure at the stadium—which had become all theirs after 1991 with the Falcons’ move to the Georgia Dome.

Not that AFCS was going to make the Braves’ lives easy during its geriatric years. Shortly before the start of a game in July 1993, a can of cooking oil tipped over in an unused suite adjacent to the press box and caught fire; flames flung out, and it took 25 minutes for firefighters to arrive and put it out. The inferno resulted in $1.5 million in damage, temporary ruin to five suites and a good portion of the press area, and igniter fuel for the Braves—who themselves caught fire starting that night with the arrival of slugging acquisition Fred McGriff, as they overcame a 10-game deficit to San Francisco and took the NL West on the season’s final day with a 104-58 record.

For all of their dominance of the National League during their last six years at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium—winning five division titles and four pennants—snatching the big prize, the World Series trophy, remained elusive. That frustration finally came to an end in 1995, when the Braves captured their first—and still, only to date—championship in a six-game Fall Classic triumph over the Cleveland Indians. Beyond the 1993 blaze, the only stadium-related issues to prop up were a couple of questionable billboards planted behind the outfield fence; one was for Hooters—you know, the restaurant chain that appeals to men willing to stare at waitresses wearing tight, low-cut shirts—while the other was for Marlboro cigarettes, which had to be covered up when the Braves landed on national TV because it technically violated laws against tobacco advertising on television.

Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium did not quietly fade to black in its last year of operation. The facility was used for the Olympic baseball competition, with the United States taking the bronze medal; two months later, the Braves went for the gold—and their second straight world title—but the New York Yankees rudely got in the way. After taking the first two games of the World Series at Yankee Stadium by an aggregate 16-1 tally, the Braves had the next three at home and had visions of victoriously closing out the Series—and their tenure at the stadium—in front of their fans, something that had never happened in major league history. But the Yankees provided the series with a stunning about face, winning all three games at Atlanta before moving back to New York to finish off the Braves.

Ashes, Asphalt and Rebirth.

As the transformation of Olympic Stadium into Turner Field across the street became more of a logistical challenge than expected in the winter to follow, there was a glimmer of hope—as perhaps defined by the few folks who didn’t want to see the Braves leave AFCS—that the old stadium might be needed for part or whole of 1997. But the miracle workers, perhaps using a page from the Heery & Heery playbook of accelerated project management 30 years earlier, got Turner Field ready just in time for Opening Day—leaving Atlanta-Fulton sitting alone and awaiting an execution date. The firing squad arrived on August 2, 1997, using 1,600 pounds of explosives to bring down the stadium and make way for additional Turner Field parking. Only the segment of the outfield wall cleared by Hank Aaron in 1974 remained; the stadium’s three sculptures, of Aaron, Phil Niekro and Georgia native Ty Cobb, were moved across the street to Turner Field’s entry plaza.

Among those who helped Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium get built and saw it all the way to its final days was Ivan Allen, Jr., the former mayor who at age 85 threw out the venue’s ceremonial last pitch. Bill Finch, the “F” in FABRAP who co-design the stadium with Heery & Heery, shed no tears over the demolition of his product, telling author Gene Asher, “I have no regrets. There is no need to treasure it. It served its purpose.”

Following the end of the Braves’ inexplicable short life at Turner Field—abandoning the ballpark for Cobb County in 2017—there would be new life for baseball at the AFCS site. Georgia State University, which bought Turner Field and turned it back into a more oval-like venue for its football team, will plant a baseball field with 1,000 seats in the Turner parking lot formerly known as Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. The new ballpark will give the fans something the enclosed AFCS never could: A view of downtown Atlanta. The outfield wall will fuse in the memorial remnant of Aaron’s 715th home run. Thus, anyone who attends a Georgia State baseball game in the near future can relax, kick back and imagine the stadium that once surrounded the field and helped introduce Atlanta into the big leagues.

The Ballparks: Turner Field How do you conceive and build a track and field facility for the Summer Olympics, tear it apart afterwards and convert it to a ballpark? Ask the folks in Atlanta, where running tracks became warning tracks, ovals became diamonds, and flags became foam tomahawks. A year after its opening, Olympic Stadium would become Turner Field, and on its stage the Braves would replace the world’s athletes and extend its reign of excellence.

The Ballparks: Turner Field How do you conceive and build a track and field facility for the Summer Olympics, tear it apart afterwards and convert it to a ballpark? Ask the folks in Atlanta, where running tracks became warning tracks, ovals became diamonds, and flags became foam tomahawks. A year after its opening, Olympic Stadium would become Turner Field, and on its stage the Braves would replace the world’s athletes and extend its reign of excellence.

The Ballparks: Braves Field Sprawling in scope and vanilla in appearance, Braves Field never captured the imagination like nearby Fenway, becoming outdated shy of its prime after being hailed as the ultimate Deadball Era park—where deep flies were kept in but thick railroad smoke couldn’t be kept out. Once the home run became trendy, one clueless owner after another didn’t know what to do with the joint—and usually they did nothing.

The Ballparks: Braves Field Sprawling in scope and vanilla in appearance, Braves Field never captured the imagination like nearby Fenway, becoming outdated shy of its prime after being hailed as the ultimate Deadball Era park—where deep flies were kept in but thick railroad smoke couldn’t be kept out. Once the home run became trendy, one clueless owner after another didn’t know what to do with the joint—and usually they did nothing.

Atlanta Braves Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Braves, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.