The Ballparks

Exhibition Stadium

Toronto, Canada

Hey Cleveland, you weren’t the only city with a Mistake by the Lake. Just off the shores of Lake Ontario, Exhibition Stadium was scrunched together as an odd marriage of baseball and football, a ballpark from the Bizarro World where only bleacher fans were covered and a scoreboard placed behind home plate. Toronto fans knew—and prayed—that it wouldn’t last for the long run, but it proved a critical stopgap that gave Hogtown a long-overdue introduction to big league baseball.

Baseball history is hardly short on tales of teams playing in temporary quarters before settling into Home, the true ballpark. There’s the forgotten parks (RFK Stadium, the Polo Grounds, Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field) briefly brought back to life out of necessity, the makeshift venue (Houston’s Colt Stadium) built completely from scratch, and the head-scratcher (the oval-shaped Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum) that just didn’t make sense for any baseball team to inhabit.

Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium presented something of a unique case. When it was transformed from a fragmented football facility into a fixed multi-purpose jumble, nobody at first was quite sure if the expansion Blue Jays would ride it for the long run or quickly start knocking on the door of local government, inquiring about a better place. Many of the fans who showed up hoped for the latter, given Exhibition’s split personality, its occasional exposure to harsh meteorological elements and the seagulls that swooped about, sometimes at their own peril—as Dave Winfield once proved.

There was real love-hate for The Ex, as it was sometimes referred to in shorthand. “It wasn’t just the worst stadium in baseball, it was the worst stadium in sports,” recalled Blue Jays exec Paul Beeston to the Toronto Globe and Mail. “But it was ours, and we were quite proud of it.” A longtime Jays fan commenting on a web page discussing Exhibition had this to say: “Terrible stadium. Freezing cold in the winter, and scorching in the summers. Windy, ugly and pretty much a disaster in every possible way.”

“But I have nothing but happy memories of the place.”

Everything But Baseball.

To understand Exhibition Stadium’s origins, you need to understand its ties to the Canadian National Exhibition, the grounds of which the stadium sat. Initiated in 1879 as the Toronto Industrial Exhibition, the event showcased the latest and greatest in agriculture, technology and good old-fashioned fairground attractions. Its popularity mushroomed to the point that by 1912 the event was rebranded by its current name to attract more national attention. It got it; today, the CNE sees over 1.5 million visitors over its 18-day period in late summer, typically ending on Canada’s Labour Day (which runs parallel to America’s Labor Day).

It wasn’t baseball but, instead, horse racing that would rule at the first sports facility planted at the Fairgrounds. The 5,000-seat structure also allowed patrons to view stage shows, livestock events, fireworks displays and other sporting competitions. It was rebuilt as a 10,000-seat grandstand in 1892, but 14 years later it was destroyed by fire. Another grandstand was built in its place, seating 16,400. Flames would eventually bring that down as well, in 1946.

Once more, a newer, bigger version of the grandstand would be built, with a critical directive to the architects: No wood. The resulting new structure was impressive: An 800-foot-long single-level grandstand, brawny in appearance and sturdy in construction, seating 20,000 and curving slightly around the expanse in front of it that now included track and field, auto racing and elaborate, massive CNE stage setups which would have impressed even Walt Disney. Beyond the sporting fields, paying customers had an unfettered view of Lake Ontario from the seats.

Growing Pains and Gains.

Through 1950, baseball as an option at CNE was a non-starter; fans would need to go elsewhere to watch the minor league Toronto Maple Leafs, the namesake of the more famous squad that played ice hockey. Baseball’s Leafs first played at Maple Leaf Park on Toronto Island, just off land from downtown; it was said to be the site of Babe Ruth’s one and only minor league home run. Next came Maple Leaf Stadium, an elegant 23,000-seat plant that opened in 1926. With its stately entrance and arched openings, the venue architecturally evoked both Yankee Stadium and Ebbets Field.

Business at Maple Leaf Stadium boomed in the 1950s thanks to owner Jack Kent Cooke, a young, enterprising local publishing and broadcast magnate who would later become more famed for his ownership of basketball’s Los Angeles Lakers and football’s Washington Redskins. The Maple Leafs were Cooke’s first foray into sports, and a rather successful one; he turned the team into a constant winner on the field and packed the ballpark, raising hope that Toronto could snare a major league franchise as baseball’s geographical entrenchment began to loosen up. It’s not that Cooke didn’t try, attempting to buy four different teams—the Philadelphia A’s, Boston Braves, St. Louis Browns and even the Detroit Tigers—with the intent of bringing them to Canada. When neither of those deals panned out, Cooke latched onto the Continental League, a proposed third circuit that would have included Toronto. But that too died when the National and American Leagues gave bones to some of the Continental owners—Cooke not being one of them—in the form of expansion. Not only was Toronto shut out of the majors, but completely shut out of baseball by 1967 when the Maple Leafs were sold and moved to Louisville as no one wanted to pay the prohibitive fee of upgrading aging, fragile Maple Leaf Stadium.

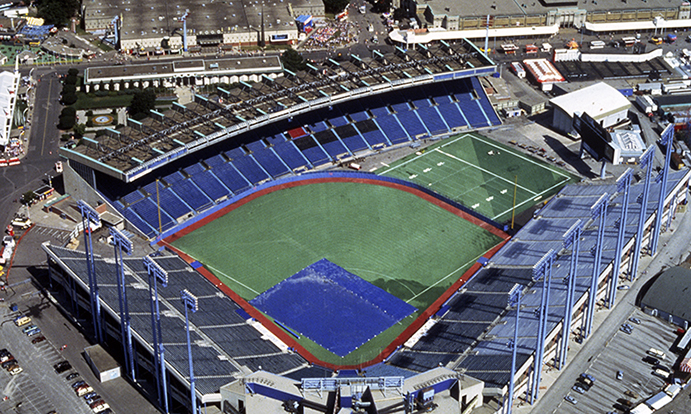

The Sybil Complex: An aerial view of Exhibition Stadium reveals the facility’s split personality via its integration of baseball and football.

Meanwhile, Exhibition Stadium was growing. In 1956, there was talk of spending $6 million to expand the facility to 64,000, but nothing actually got done until 1959 when a simple, smaller uncovered section was put up on the south, opposite side of the primary grandstand. The 12,400-seat addition was to be the first of a three-step upgrade that would ultimately allow the possibility of baseball at Exhibition, but Step One was as far as it got. It did, however, manage to lure its first pro sports tenant in the Canadian Football League’s Toronto Argonauts, who inaugurated its tenure at Exhibition with a preseason game against the NFL’s Chicago Cardinals—the first contest ever played between the two leagues. The Cardinals romped, 55-26, in a game using a hybrid of Canadian and American rules.

Baseball’s absence in Toronto stung the city, and it continued to try to find solutions to fill the void. A domed stadium—it would actually be called the Metrodome, 10 years before Minneapolis borrowed the name—was drawn up as one such solution in 1971, to be placed on grounds near Downsview Airport some six miles northwest of downtown. Everyone thought it was a great idea, but no one wanted to pay the $45 million to build it.

Finally, amid rumblings that Exhibition Stadium might be torn down, city officials finally put their money where their mouths were and voted to add a baseball-style configuration to the venue. The $17.5 million expansion would basically be done on spec; even if Major League Baseball still wasn’t interested in Toronto, at least it no longer had the excuse to say there was no place in town to play.

It didn’t take long for Toronto to see its gamble pay off.

So Close—And Yet So Far.

The San Francisco Giants were bereft of star talent and drawing horribly at Candlestick Park, and longtime owner Horace Stoneham wanted out. Nobody in the Bay Area was willing to buy, but folks in Toronto—led by bigwigs at the Globe and Mail and local brewery Labatt—were. The deal to move the Giants to Canada was signed and sealed, but the city of San Francisco sued to halt it from being delivered. The resulting delay allowed local California interests to step forward and steal the team back, but Toronto’s misery was short-lived when the American League rewarded one of two newborn franchises to the city with play to begin in 1977.

The expansion to welcome the Toronto Blue Jays made Exhibition Stadium look like two venues in one, with laid-back baseball seats hugging the infield and down the lines, while the original football grandstand towered behind the right field fence and peeled away past center field toward baseball irrelevance. Rarely was the far end of the grandstand inhabited by Blue Jays fans, but when it was, binoculars were a must; the farthest seat measured a whopping 820 feet—or over a sixth of a mile—away from home plate. “Those bleacherites are closer to catching a street car than a home run ball,” wrote the Globe & Mail’s Larry Millson.

For those sitting more closely to the action in the newly constructed baseball structure, it was a much different experience. Fans entered through a new entry behind home plate, where various layers and levels jutted out here and there like a stack of polygonal coasters loosely piled on top of one another. The best seats beheld great views as there was little foul territory to offer, but the problem was there were a lot of distant seats behind them. While three sections behind home plate rose 30 rows before being cut off by a level of 12 luxury boxes topped by a press box, the sections stretching down the line had an additional 30 rows tacked beyond, and at a fairly shallow pitch—which meant that the guy sitting in the 60th row could almost start to relate with those sitting way far away in the grandstand bleachers.

There was additional oddity in that while all seats on the third base side had seatbacks, the same could only be said for the lower half of seating along the first base and right field line; above and beyond well past the foul pole, fans had to settle for aluminum benches. This certainly must have left those who came to watch football scratching their heads, trying to figure out why the 55-yard-line seats physically resembled something only bleacher bums could love.

A look back at the infield and prime baseball seats from atop the football grandstand; beyond is Lake Ontario. The scoreboard above the press box was ideally placed—that is, if you were on the field or in the bleachers. (Jerry Reuss)

It’s Snowtime, er, Showtime!

After a decade without baseball, folks in Toronto certainly couldn’t be faulted for their impatience waiting for the Blue Jays’ debut. But it would have been wise for the schedule maker to let the Jays start their existence on the road and give Ontario a little more time for spring to settle in before Exhibition Stadium could host its first games. As it was, the Jays began with a seven-game homestand—and the inaugural contest by itself probably left MLB execs wondering if Fairbanks would have been a better alternative for expansion. The Jays and Chicago White Sox were welcomed on April 7, 1977 by 44,649 fans, dignitaries and a late winter snow that covered the artificial turf in a coat of white. But the game played on, even as wind chill readings reached a mere 10 degrees; a Zamboni was brought over from Maple Leaf Gardens and occasionally cleared the snow off the field.

The Blue Jays won the opener, 9-5, and five of the seven games on the first homestand—but were 20-53 at Exhibition Stadium for the remainder of the season, with one of those victories handed to them in September when the visiting Baltimore Orioles and testy manager Earl Weaver refused to take the field because umpires refused to remove bricks that were holding down a tarp over a bullpen mound in foul territory. Toronto went home with a 9-0 forfeit victory.

Despite the expected misery that greets most expansion baseball teams in their infancy, Toronto fans embraced the Blue Jays and proved why the city shouldn’t have been ignored as, previously, the largest market in the U.S. and Canada without major league representation. Over 8,000 season tickets were sold for the first campaign, and 1.7 million fans in total showed up to rank the Jays fourth out of 14 AL teams even as their record was 14th of 14 at 54-107. The script remained the same for the next five years; the Blue Jays stunk, but the fans kept showing up. In fact, enough fans had passed through the gates after three years that a clause was activated that would have “entitled” the Jays to request a second-deck on the first base side. That didn’t necessarily mean that such a request would have been okayed, and the Jays never made it anyway.

One necessity added after the first season was a large scoreboard at the end of the seats down the right field line. It had to be huge to be seen, standing almost 200 feet beyond the outfield fence so it didn’t impede upon the football field alignment. A second, smaller scoreboard was much closer, but few people saw it—because it was placed atop the press box behind home plate. The board was outside the peripheral vision for most fans except those in the grandstand bleachers who, between this and the fact they were the only fans covered by a roof, must have felt blessed with some sort of anomalous royalty. (Exhibition Stadium was, in fact, the only major league facility where only the bleacher seats were covered.)

The fans at Exhibition Stadium were considered some of the quietest and nicest in baseball. Visiting players soon found out why: It was, at the time, the only major league ballpark that didn’t sell beer. That changed at the end of July 1982, and the difference was deafening. Entering the season, the Blue Jays had never posted a winning record at home, and through July were skirting right at .500. But after the beer started flowing and—gee, what do you know—the crowds started getting more rambunctious, it had a definite effect on the players who felt more vocal support; the Jays were 19-12 at Exhibition after the ban was lifted and never again finished below .500 playing at home, or at least until they went 12-14 in their partial 1989 campaign at Exhibition before moving midseason to Skydome.

A view down the right-field line shows the extension of seats along the first base-side well past the foul pole; beyond that is the main scoreboard, nearly 200 feet behind the right-field fence. (Jerry Reuss)

Flock at Your Own Risk.

Joining the multitude of Toronto baseball fans at Exhibition was the multitude of ring-billed gulls that flocked off of Lake Ontario and patiently waited until the final out before descending on the emptied-out seats for leftover scraps of hotdogs, popcorn and nachos— a scene fans today at San Francisco’s AT&T Park can relate to.

The presence of the gulls led to Exhibition Stadium’s most notorious moment.

On a mid-summer evening in 1983, the Jays and the New York Yankees brought 36,000 fans to The Ex. In between innings with Toronto due up, Yankees outfielder and future Hall of Famer Dave Winfield wrapped up his warm-up tosses by throwing the ball to the team’s batboy near the dugout. Unfortunately, it made a direct hit on a seagull minding its own business on the turf, killing it instantly. Winfield took his cap off and placed it over his heart as a mock funeral service gesture, which didn’t score many points with the Toronto crowd that raged and booed. Oh, if only they had extended that beer ban, Winfield probably was thinking.

An off-duty police officer working sideline security near the Yankees dugout—who to this day still believes Winfield intentionally hit the bird—had him arrested after the game on a charge of animal cruelty. Blue Jays management, who were just as incredulous over the charge as Winfield, came to the police station to bail the Yankee star out. His manager, Billy Martin, had this to say: “They wouldn’t say (he hit it on purpose) if they’ve seen the throws he’s been making all year. It’s the first time he’s hit the cut-off man.” Toronto’s vilification of Winfield would be softened nearly a decade later when, while wearing a Blue Jays uniform, he became a primary factor in helping the franchise win its first world title.

On the field, Exhibition Stadium favored the hitters on a setting tailor made for the 1970s and 1980s, with a generic symmetrical set-up laid out on a hard, bouncy artificial turf in front of a standard 12-foot chain-link fence, the bottom eight feet of which was padded. Reaching for the fences just 330 feet down the lines, 375 to the gaps and 400 to dead center didn’t seem too difficult; the Baltimore Orioles understood this in ways they’d rather not remember. In 1978, the toddler edition of the Blue Jays scored 24 runs off the Orioles in the first five innings alone before coasting to a 24-10 win; and in 1987, almost 10 years to the day that the Orioles walked off the field rather than play with bricks holding down the bullpen tarp, Toronto crushed 10 home runs—three alone from catcher Ernie Whitt—to set a major league record for the most by one team in a single game. The 18-3 Toronto rout got so out of hand that the Orioles benched ironman shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. midway through—ending his record run of 8,243 consecutive innings played.

Almost.

Some of the game’s best pitchers of the day were constantly rattled when visiting Exhibition Stadium. Bret Saberhagen was 1-4 with an 8.51 ERA at The Ex. Frank Viola was 2-9 with a 5.76 mark. Mark Langston, 1-6 and 6.58. But their frustration of looking clueless on the mound paled to the frustration experienced by the Blue Jays of being that “almost” team as they became more competitive in the standings.

Almost was 1985, when the Blue Jays finally made it to the postseason and took three of the first four games against Kansas City in the American League Championship Series. In previous years, that would have been good enough to get to the World Series, but this was the first season that baseball extended the LCS to a best-of-seven format. The Jays couldn’t seal the deal, losing the next three games—the last two at Exhibition Stadium.

Almost was 1987, when Toronto blew a 3.5-game lead with seven games to play—seven games they all lost, four of them at The Ex.

Almost was September 28, 1982, when the Jays’ Jim Clancy lost a perfect game in the ninth inning against Minnesota when leadoff hitter Randy Bush broke his bat and poked a soft single to right field.

Almost was September 30, 1988, when veteran Toronto ace Dave Stieb lost his bid for a no-hitter with two outs in the ninth when Baltimore’s Jim Traber singled. It was the second straight game that Stieb blew a shot at a no-no with one out to spare, having felt the agony of almost six days earlier in Cleveland. After the second oh-so-close effort, Stieb summed up the Blue Jays’ existence at Exhibition: “The story of our team.”

As it was, there was never a no-hitter thrown in 12-plus years of baseball at Exhibition Stadium. No World Series games. No All-Star games. The Ex had to settle for second-tier pageantry such as the Grey Cup and the Soccer Bowl.

Jesse Barfield hit the most home runs at Exhibition, with 99. Damaso Garcia had the highest career batting average of any Blue Jay at the venue, at .2996—technically .300, but not a true .300 as Ted Williams would have argued. Almost, almost, almost.

The Ex-Ex.

There was no illusion that Exhibition Stadium could make it as a long-term solution for any of Toronto’s pro sports teams. The Blue Jays had plenty to grumble about all on their own. The lakefront weather was never always postcard-picture perfect; besides the early season snow, there was also the wind, which once played such havoc at one 1984 game that umpires said enough after just five pitches due to 60-MPH gusts that kept blowing pitchers off the mound. There was the odd seating conditions, including the aforementioned distant grandstand seats and overflow media space for the 1985 ALCS both in the left field corner and atop the grandstand, a long way away from home plate. There was the occasional inconvenience of using the ballpark, best recalled in a 1980 game that was called on account of curfew…at 5:00 p.m. Reason? The Ex had to be cleared out for a concert featuring The Cars later that evening. And there was the lack of revenue the Blue Jays collected at the facility, with only 16% of all concessions and no parking going into the Jays’ coffers.

Ironically, the event that once and for all convinced Toronto power brokers to move indoors from The Ex was a cold, hard, gusty rain that punished football players and fans alike in the 1982 Grey Cup. Within a few years, architects publicly revealed the first sketches of a new domed facility that would ultimately be named Skydome first, Rogers Centre second.

The Blue Jays bid adieu to Exhibition Stadium much the same way they hailed bonjour to it—with a win over the White Sox. The only difference was the weather, which was far balmier than the snow-swept 1977 debut. After George Bell’s 10th-inning homer clinched the win, numerous security personnel including mounted police quickly enveloped the field to prevent fans from invading and snatching on-field items, but they weren’t quick enough to stop several White Sox players who took off with the bases.

After Skydome became the center of the Toronto sports universe, Exhibition Stadium trudged on, hosting mostly big-name concerts such as the Rolling Stones, U2, David Bowie, Metallica, and Paul McCartney. It was demolished early in 1999; seven years later, a new 20,000-seat soccer facility named BMO Stadium was erected on the site for Toronto FC, a Major League Soccer expansion club. A 2015 increase in seating to 30,000 was good enough to lure the CFL’s Argonauts back from Rogers Centre.

Beyond the memories, baseball hasn’t been totally forgotten on the site of the ex-Ex. On the parking lot just south of BMO Stadium, you can find markers indicating where all four bases were once located. You won’t find Blue Jays around anymore, just seagulls and other birds who now pray upon the scraps left behind by BMO’s faithful fans.

Whether they’re still looking to get even with Dave Winfield is another question.

Toronto Blue Jays Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Blue Jays, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.