The Ballparks

Globe Life Park

Arlington, Texas

(Wikipedia—Dopefish)

When the Dallas-Fort Worth suburb of Arlington took in the Texas Rangers in 1972, it welcomed them to an overgrown minor league facility that did the team’s karma no good (read: no postseason) for 22 years. Then it built Globe Life Park, and the magic arrived in the form of four first-place finishes in its first six years. It certainly provided overtime fun for employees “working” in the business offices behind the center-field fence.

Say this about Globe Life Park: It didn’t lack for character. And when we mean character, we mean lots of it—and in many forms. The ballpark dripped with multiple personality disorder. The arches that dominate the outer layers of the ballpark are derived from Chicago’s old Comiskey Park. There’s the left-field wall that echoes Fenway Park’s Green Monster. Oh, and over behind right field, there’s a double-decked bleacher pavilion modeled after Detroit’s extinct Tiger Stadium. And look to the top of the upper deck, and you’ll see a generic take on Yankee Stadium’s more elegant, classic overhead frieze. Even the nameplate on the outside entrance changed three times. Sally Field’s schizophrenic character from Sybil could have showed up and wondered aloud, “Can’t this place make up its mind?”

There’s a more invisible homage to old Arlington Stadium, the facility that preceded Globe Life Park as the Texas Rangers’ home: The stifling, inescapable heat. And while there was more shade to keep less fans exposed from the boiling Texas sun, summertime temperatures often remained at or close to 100 well into the late innings. Such heat would ultimate seal the ballpark’s fate—much earlier than expected.

On the outside, Globe Life Park has a more distinctly Texas character. The exterior is dressed with a graceful combination of granite and brick, alternatively adorned at top with lone stars and longhorn steers made from cast stone. Below, topping the lower row of arches, is a series of subtle relief murals depicting famous moments in Texas history.

Globe Life Park’s kitsch isn’t restricted to the ballpark structure. Nearby street lamps, freeway overpasses and signage are decorated in elegant, antique iron stylings, as if the ballpark has literally taken root and spread its aesthetic touch throughout the town like vines. Give the City of Arlington, arguably the nation’s most active playland between Anaheim and Orlando, credit for putting on the dog.

Of course, the trick of getting to Globe Life Park and its generous amount of street-level parking lots was, well, getting there. Roads, boulevards and freeways are abundant, but like most roads in Texas, they’re always under construction. It’s the law of the Texas Department of Transportation; when you’re done building a road, rebuild it.

Heat and traffic cones aside, Globe Life Park provided welcome, big-time ballpark relief for Rangers fans, who certainly rank among the friendliest in the majors. They understand that their home wasn’t perfect—opinions about the place vary wildly, both inside and outside of Arlington. There is one thing, however, that everyone can agree on: Globe Life Park was light years ahead of its predecessor, even if it looks “older.”

Bushing the Envelope.

When a local group publicly fronted by future Texas Governor (and future U.S. President) George W. Bush bought the Rangers early in 1989, it instantly completed Job One: Keeping the team from leaving Arlington, after outgoing owner Eddie Chiles had threatened a move to St. Petersburg. Job Two lay ahead: Leaving Arlington Stadium. The 25-year-old ballpark, over-modulated from a small minor league facility to a 40,000-seat eyesore featuring no shade, no allure and no chance whatsoever of winning any architectural honors, was a non-starter for the new regime. It wasn’t just an aesthetic issue, but a financial one; the Rangers couldn’t run the franchise in the black even if they sold out the old joint every night. A new ballpark was sorely needed. The Rangers knew it, the fans knew it, and the politicians in Arlington knew it.

A classy variation of the Rangers’ logo is placed on every aisle-facing seat at Globe Life Park.

Late in October 1990, any lingering suspense was killed when the Rangers announced they had agreed with the Arlington to build a new yard. But now they needed less than three months to get the residents to agree through a ballot initiative. The measure called for the raising of the city’s sales tax by a half-cent to cover 70% of the ballpark’s projected $165 million tab, with the Rangers on the hook for both the remainder and any overages. There was more: The deal would also give the Rangers control over what they could develop not just inside the ballpark, but also in the immediate surrounding area—using the power of eminent domain through Arlington to condemn any land they had their eyes on without having to buy it on the open market. That last bullet point was one that raised the most eyebrows, seeing that eminent domain usually applied to public projects, not one that would purely benefit a private entity such as the Rangers.

Polling on the ballpark measure in advance of the vote was murky and left the Rangers nervous. They relied on two popular figures to get out the yes vote: Ace pitcher (and Texas native) Nolan Ryan, and Bush, who had a special gift for connecting with people with his chummy, good ol’ Texan attitude. Arlington Mayor Richard Greene campaigned more on shock value, warning that a no vote would seal the Rangers’ fate in Arlington and force the town to “settle for mediocrity.”

With political experts judging the vote to close to call just three days before the polls opened, a new wrinkle developed: The start of the Gulf War. Pro-ballpark forces feared that voters already weary of a shaky economic outlook would feel further uncertainty over the massive military response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait—a response led by Bush’s father, President George H. Bush—and doom the vote. But on Election Saturday in Arlington, a stunning 65% of a record turnout said yes to the measure. Euphoria replaced angst at Rangers headquarters as the virtual mandate affirmed Arlington voters’ belief that entertainment—whether via the town’s theme park, water park or the Rangers—made up the bread and butter of their revenue.

Globe Life Park’s primary seating extends around the left-field foul pole and behind the 14-foot-tall out-of-town scoreboard—which until 2009 was hand-operated.

Of Stars and Steers.

The hard part done, the Rangers switched gears to something much more fun: The process of hiring an architect. They invited just about everybody to this party, sending a request for proposals to 26 different firms from the top dogs to relatively local, obscure shops. Nine of them declined the invitation, critical of the RFP’s vagueness and the potential for unfair competition it would thus create.

The Rangers’ lack of direction translated to a wide-open palette of inventive ideas from the participating architects. Southwest designer Antoine Predock, who would later have a hand in idealizing San Diego’s Petco Park, conceived a ballpark built into an artificial, wildflower-laden hill (echoing Dodger Stadium), which must have sounded nice to the Rangers until discovering that Predock situated parking lots far away from the venue—meaning fans would be forced to take a long, uphill walk in the Texas heat to reach the turnstiles. Austin-based Moore/Anderson devised a partitioned façade that came straight out of a Western movie set. Fort Worth’s Martin Growald envisioned a ballpark topped by numerous tall sails rising from an arched scaffolding inspired by the Eiffel Tower. Ellerbe Becket, the future architect of record for Phoenix’s Chase Field, suggested parking lots shaped in the State of Texas.

Standing out among the myriad of proposals, pricey models and renderings was Washington D.C.-based architect David M. Schwarz, whose less ambitious but thoroughly Texan ideas struck the right chord with the Rangers review team, led by Bush and club president Tom Schieffer (the younger brother of CBS anchorman Bob Schieffer). Though he was technically an out-of-towner, Schwarz was already a known quantity within the Metroplex—particularly in Fort Worth, where he was already deeply involved in a master plan for the city. But his presentation of a new Rangers ballpark, the look of which would survive fairly intact through to its final construction, made him a regional star that would ignite a cache of future local projects. These would include Dallas’ American Airlines Center (home of the NBA Mavericks and NHL Stars), which is what Globe Life Park might look like with a roof on top; Frisco’s Dr. Pepper Ballpark, a minor league facility with edifices inspired from Churchill Downs; and numerous Fort Worth facilities including Bass Performance Hall, Sundance Square and Dickies Arena (completed in 2019). Many of Schwarz’s buildings contain the Globe Life Park touch—a blending of classical and colonial styles spiced with a dose of natural Texas warmth.

The Rangers’ vision of the new ballpark extended beyond the playing structure itself. They dreamt of using the surrounding acreage for a lake, a San Antonio-like riverwalk flanked with shops and restaurants, an amphitheater seating anywhere from 5,000 to 25,000, a Little League ballpark modeled after the big guy, a mini- Hall of Fame featuring baseball artifacts borrowed from Cooperstown, and a Smithsonian museum. Heck, the Rangers thought, if we had money left over from the budget, we could even build a monorail linking the ballpark with the nearby Six Flags amusement theme park. The idea was to create a mixed-use nirvana, a “superpark” as Tom Schieffer termed it, to manufacture a city center that Arlington, a suburban blob, lacked.

The spacious lobby that surrounds much of Globe Life Park includes two field-level concourses, the ceilings for which are identified through dark green steel trusses to give the area necessary panache.

Predictably enough, steamrolling through the surrounding land through eminent domain led to plenty of work for local lawyers. One 13-acre tract of land north of the ballpark, owned by a trust set up by electronics retailer magnate Curtis Mathes, would prove particularly troublesome. The Arlington Sports Facilities Development Authority, a co-creation of the City of Arlington and the Rangers, offered to buy the land for $1.5 million. The Mathes family countered with $2.8 million. Rather than meet halfway with an agreement, the ASFDA went hardball and instead halved their first offer to a take-it-or-be-seized $800,000. The New York Times witnessed and remarked that even “Kazakhstan would blush at such practices.” The Matheses sued, and 10 years later were awarded nearly $5 million, a figure that grew to $10 million via interest as the Rangers and Arlington bickered over who should pay. (The Rangers ultimately caved.)

Other, financially less costly P.R. headaches surfaced during construction of the ballpark. Minority firms felt left out of the contracting process, and an attempt by Schieffer to make peace with them at a meeting failed miserably as he absorbed two hours of nonstop grilling. And when the Rangers wanted to name each of their 15 parking lots after historical Texan figures, they came under fire for not including more women and minorities among the heroes.

More puzzling was the reaction to the venue’s new name: The Ballpark in Arlington. You’ve got the city included, there’s no corporate sponsor—everyone’s happy, right? Wrong. When the name was first announced late in 1993 during a Rangers game at Arlington Stadium, the crowd booed. “Boring, bland and abysmal,” is the feeling Fort Worth Star-Telegram writer Kathryn Hopper gathered from the reaction. The negativity wasn’t just restricted to those seated within the old stadium; a local poll found that 70% of the respondents disliked the new name as well.

Night at Globe Life Park brings to life backlit lone stars and steer heads, and baseball-themed lamps on the upper concourse. (Flickr—Caleb Feese)

So Much to Absorb.

After a dry run with an exhibition game against the New York Mets, the Ballpark in Arlington’s true grand opening took place on the not-so-dry day of April 11, 1994, as rains delayed the first pitch by nearly an hour. The national anthem was performed by acclaimed area-born pianist Van Cliburn backed by the Fort Worth Symphony, seated on folding chairs in the infield. The visiting Milwaukee Brewers ruined the day on the field, keeping the Rangers barely at arm’s length throughout and prevailing, 4-3—but the true star of the day was the ballpark itself, as 46,056 fans reveled in an environment that was night and day compared to the uninspiring Arlington Stadium. David Schwarz, soaking in the reality of his architectural vision, was stunned to find fans seeking his autograph, which undoubtedly left him wondering how he was recognized in the first place.

One fan was too broken up, literally, to get Schwarz’s signature. Moments after the game, 26-year-old Holly Minter posed for a picture by sitting on a front-row railing in the upper deck of the right-field grandstand. Then, suddenly, she fell, 35 feet below to the lower level. The damage she sustained was almost as painful to read about as it was to feel: Two broken ribs, a broken vertebrae, a broken shoulder and six broken teeth. She recovered to tell about it, and the first thing she probably would have told the Rangers—besides, maybe, “You’ll be hearing from my lawyer”—was to raise the railing. They did, from 30 inches to 46—while becoming the first major league ballpark to post signs warning fans to be careful. Despite these new measures, Minter unfortunately would not be the first to take the plunge at the Ballpark in Arlington.

Reviews of the Rangers’ new palace ran the gamut. The Houston Chronicle’s Dale Robertson said, “It’s even funkier and more chock-full of gimmicks in person than photographs convey.” Author Matt Lupica called it “scintillating.” CBS Sportsline, in a more dissenting opinion, said the Ballpark in Arlington “tries too hard” and criticized the venue’s lack of intimacy—especially with an upper deck that, it believes, could have easily been situated closer to the field.

There was little debate that the Ballpark in Arlington had much to absorb. On the outside, the square-shaped structure has an orderly look to it, with its double-decked system of open-air arches adorning the full circuit. More formally, the four main entrances were spaced apart at each corner, accommodating fans arriving from various parking lots randomly spaced from all directions. Of these entries, the home plate gate is the most photogenic; it looks out onto a green expanse of parkland, casually dotted by shade trees and split by a man-made, 12-acre lake named after late Rangers broadcaster Mark Holtz. The far side of the park includes Texas Rangers Youth Ballpark, a 650-seat ballyard also designed by David Schwarz that echoes Globe Life Park’s architectural styling. It’s used primarily for Little Leaguers and average Joes for whom 360 feet around the bases is too much.

Once you passed through Globe Life Park’s main corner gates, you found yourself within the ballpark’s expansive interior that surrounds the seating bowl. It featured two lower-level concourses: An outer lobby that rose 70 feet high, and an inner walkway with a lower ceiling with access to most of the main lower-level concession stands. To give the beige aluminum ceiling paneling of these two concourses more flair, arched steel trusses painted in dark green and highlighted with the Texas lone star were spaced apart roughly every 20 feet. The combined effect of the trusses and the outer open-air arches led art historians to compare the concourse to France’s 800-year-old Chartes Cathedral.

Besides giving fans a chance to feel shade from the often-merciless Texas summer heat, the main concourse also provided room to hide a series of massive, maze-like spectator ramps (located inside the northeast and southwest entrances) from the outside, maintaining the structure’s external aesthetic dignity—in stark contrast to the multi-purpose stadiums of the 1960s and 1970s and, more recently, with Chicago’s Guaranteed Rate Field. Fans entering through these gates felt overwhelmed by the presence of these immense, skeletal steel ramps.

Inside the ballpark bowl, Globe Life Park contained three seating levels from foul pole to foul pole, bending around the left-field pole for another five sections or so. The ballpark’s 127 suites—all named after Hall-of-Fame ballplayers—were broken into two levels, one each above and below the second (club) level. This was done to minimize the perception of “distinctions in class,” as David Schwarz told the Washington Post.

Every suite at Globe Life Park is named after a Hall-of-Fame player, such as this one for Lefty Grove.

Globe Life Park’s true inside kitsch kicked in where the three main levels end. Prominently rising behind right field was the Home Run Porch, a double-deck grandstand topped by an A-frame roof that drew immediate comparisons to Detroit’s Tiger Stadium—although that’s something of an exaggeration given that the second level doesn’t lurch out over the warning track. Old-time limitations were the rule in the Home Run Porch, from steel support columns that obstruct a full view for patrons seated behind, to blocked views of deep right field up in the second level. Ceiling fans placed above were so high above the seats, there was no way they could possibly make any impact on the human fans below. One would have also thought that the Home Run Porch would house the cheapest seats in the house, but they didn’t; that distinction belonged to the third-deck seats within the main seating structure. For those seated in the Home Run Porch’s upper level, there was one perk that justified the expense: “All-you-can-eat” access to standard ballpark food fare (except, of course, beer) from a food court situated behind the seats.

Beyond the Home Run Porch, there were other odes to classic ballparks, past and present, to be found at Globe Life Park—though they weren’t entirely convincing. The upper-deck overhang was graced with a white frieze that generically mimicked Yankee Stadium’s iconic design. And the tallest portion of the outfield wall, in left field, was promoted as emulating Fenway Park’s Green Monster—though its 14-foot height would greatly pale against Boston’s legendary barrier, which rises 37 feet. Even the hand-operated out-of-town scoreboard initially included within the wall was converted into a less wistful, electronic version in 2009.

The double-decked Home Run Porch behind right field brings back all the restrictive nuances of old-rime ballparks, including view-blocking steel posts and limited sightlines.

A View From the Cubicle.

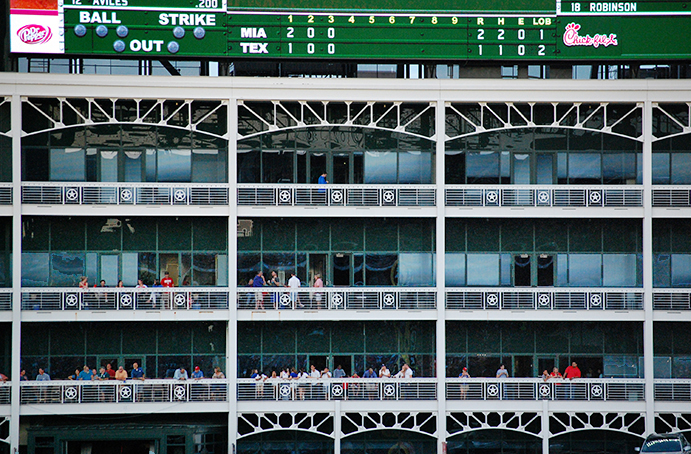

Completing Globe Life Park’s enclosure, in center field, was the ballpark’s truly unique feature: The office spaces. Standing four stories tall, the offices featured an elegantly industrial white façade, balconies and floor-to-ceiling windows for tenants to easily be distracted—especially if there was a game going on. Actually, the middle two floors were for commercial tenants only; the first level was occupied by retail, restaurants and interactive displays accessed by fans, while the upper floor was used by the Rangers for their corporate offices—a late addition in the building process that the team pitched in $1 million to construct. Architect Bryan Trubey of HKS, one of the firms partnering with David Schwarz on the ballpark’s design and production, told Sports Illustrated 20 years after the venue’s opening: “The ballpark-facing side of the office buildings has porches and balconies continuously along at every level. It really helped us create a focus, an intimate feeling on the inside of the building.”

The offices were a hot item when the ballpark opened and has remained so throughout its lifespan. Among the original tenants were Dallas Cowboys quarterback Troy Aikman and an orthodontist named Rick Herscher; if that latter name sounds somewhat familiar to hardcore baseball fans, it’s because he played one year in the majors—hitting .220 for the notoriously awful 1962 New York Mets (40 wins, 120 losses).

The glamour of having an office at Globe Life Park was that when you’re done for the day, you can step out on the balcony and watch the Rangers. But you’re not likely to see everything; the Hyundai Club, situated atop the grassy Greene Hill incline behind the center field wall, obstructed the views of most tenants, especially those on the second level. But hey, beyond the rent, the games were free—right? Well, not always. When the Rangers made the playoffs in 2010, Major League Baseball—perhaps worried that visitor activity at the offices would suddenly shoot through the roof—fired off a directive to the team to force tenants to pay $25 per head if they stayed to watch the American League Division Series against Tampa Bay from their offices. That figure went up to $40 per game when the Rangers advanced to the ALCS against the New York Yankees, and $50 when they reached their first-ever World Series, against San Francisco.

Perplexed tenants, who never had to pay when the Rangers made the playoffs repeatedly during the late 1990s, were not happy. One complained that the lease stated that his office and the balcony was technically “not part of the ballpark.” The Rangers argued back, with team exec Rob Matwick stating: “You’re guaranteed the space, but the space doesn’t necessarily guarantee a view. And baseball has said, ‘If people are going to watch the games, you need to pay for it like everyone else.’” So much for perks.

Globe Life Park includes two floors of office spaces for outside tenants who take advantage of after-hours work and step out on the balcony to watch Rangers games for free.

Hitting and Winning.

In 22 years at old Arlington Stadium, the Rangers could only dream of making the postseason. It was hoped that the Ballpark in Arlington would provide the Rangers, a competitive team if not a contender in recent years, with that extra push to finally make relevant October baseball a reality in the Metroplex. To that end, their 1994 debut at the new yard provided enough twists and turns to humble a contortionist.

As the venue began to be established as a hitter’s park, along came Texas southpaw Kenny Rogers—who on July 28 threw the seventh perfect game in AL history by retiring all 27 California Angels. (No one else threw even a no-hitter at the ballpark.) Then came the realization that the Rangers might actually make the postseason in Year One at the Ballpark in Arlington—even with a 52-62 record, which was good enough to lead the newly-realigned four-team AL West on August 11. But that’s as far as the Rangers—and the rest of baseball—would get in 1994; that day, the players went on strike to protest the owners’ plans to initiate a salary cap. By the time the work stoppage came to an end—over seven months later—the rest of the 1994 season, including the World Series, had long since been cancelled.

Rogers’ perfecto would undoubtedly be the sweet memory in his turbulent Texas tenure. He’d have some sour moments, too—such as the time he roughed up some cameramen filming him doing pregame stretches in 2005, leading to a 20-game suspension (reduced to 13 by an arbitrator). Nevertheless, no one would win more games at Globe Life Park, as Rogers racked up 49 victories against just 25 losses.

The early years at the Ballpark in Arlington would be chalk full of good times and memorable moments beyond Rogers’ perfection. The 1995 All-Star Game was held there, with four home runs accounting for all five runs in a 3-2 National League victory. Two years later, the ballpark hosted baseball’s first regular season interleague game when the San Francisco Giants came to town and logged a 4-3 victory. Former Ranger Darryl Hamilton had the first interleague hit while leading off for the Giants, and nine innings later made the last putout in center field—lobbing the ball into the bleachers to the groans of Hall-of-Fame officials expecting to get a hold of the historic souvenir.

Best of all, the Rangers were winning in the new ballpark. In a four-year stretch during the late 1990s, they won the AL West three times—with much more respectable records than 52-62—but they also had the lack of fortuity to sync their fortunes with those of the almighty New York Yankees, who in each of those campaigns began their warpath to a world title by easily dispensing of the Rangers in the first round of the playoffs.

Some teams win with pitching, others with defense. For the Rangers, it was all about the hitting. It didn’t take long for the Ballpark in Arlington, with gratuitously asymmetrical field dimensions that favored the hitter, to gain a reputation as a slugger’s paradise. Conditions became even more hitter-friendly in 1996 when the Rangers placed the Cuervo Club, an expansive, posh lounge/restaurant, behind home plate. One might ask: How does a restaurant boost slugging percentages? Because it was built in what was previously an open area where prevailing winds from the southeast (or center field) breezed through. The Cuervo Club’s presence blunted those winds and turned them back toward the outfield—giving hitters an extra push toward the fences.

The results were telling. The Rangers nearly hit .300 at home from 1996-97. The following two years, they surpassed the barrier—batting .304 in each season. In 2005, they set an all-time major league record by bashing 153 homers at home, including a Globe Life Park-record eight in a game, twice. In one 1996 game, the Rangers led Baltimore, 10-7, and headed to the bottom of the eighth looking for insurance. They got it. Sixteen runs, one shy of the all-time record for an inning, plated for Texas as they went on to defeat the Orioles, 26-7.

Individually, numerous star Rangers feasted on the ballpark, which likely provided more juice to enhance the stats of Juan Gonzalez, Rafael Palmeiro, Ivan Rodriguez, Jose Canseco, Alex Rodriguez and Nelson Cruz than any steroids they may have taken. Some of the players’ home splits were enough to make others content had they done it over a full 162 games. When Palmeiro returned to Texas in 1999 for his second tenure with the Rangers—and his first at the Ballpark in Arlington—he hit .325 with 28 homers and 83 RBIs just at home. Three years later, Alex Rodriguez—in the midst of his short but very productive time with the Rangers—smacked 34 homers at the yard with 82 RBIs. In 2005, Mark Teixeira collected 30 homers and 88 RBIs at home. Josh Hamilton, in his 2010 MVP campaign, batted .390 at the ballpark with 22 homers and 57 RBIs in just 69 home games; he was so feared in Arlington, the opposing Tampa Bay Rays once intentionally walked him—with the bases loaded.

Of course, the hitting conditions ran both ways at Arlington as opponents enjoyed stepping up to the plate just as much as the Rangers did. In 2008, visitors scored 511 runs and helped to drive the total scoring at the ballpark on the year to 996, an average of 12.2 runs per game—or three more than the average at all other 29 MLB ballparks. Before joining the Rangers at the twilight of his Hall-of-Fame career in 2010, Vladimir Guerrero hit .396 as a visitor at Arlington with 15 homers in 53 games.

In 2013, the Cuervo Club—the culprit for all of this offensive madness, and now known as the Capital One Club—was relocated, opening the space back up behind the field level and main concourse for the winds to flow through. Accordingly, hitting levels dropped. Home runs fell by 20%, scoring by 17%, and the ballpark’s batting average slimmed 15 points down to .257—the lowest in Globe Life Park history. The numbers teeter-tottered about afterward, but they were more muted than the stat-engorging period of the 1990s and 2000s.

Visitors entering the first- and third-base entrances immediately find themselves surrounded by an overwhelming maze of spectator ramps, hidden within the ballpark structure to maintain Globe Life Park’s outer aesthetic dignity.

The Gong Show.

Globe Life Park’s eight different wall angles evoked older ballparks that couldn’t go symmetrical because their field dimensions were dictated by the surrounding street grid. Which makes Globe Life ironic, as redirected streets and evolving development accommodated the ballpark, not vice versa. For the most part, business interests responded to the Ballpark in Arlington’s presence shortly after its opening; the hospitality industry was especially active, with 10 new hotels built within a few miles of the ballpark during the 1990s. Yet the immediate area around the ballpark, which had been reserved for the visionary regime of George W. Bush, Tom Schieffer and Co. during the early 1990s, remained largely vacant of actual development. No amphitheater, no commerce-intensive riverwalk, no Smithsonian. Just parking lots and a pretty park with a lake cutting through it.

By 1998, the eyes of Bush, now the Governor of Texas, were upon the White House. He completely divested himself of the Rangers, making a handsome $15 million return on his original $600,000 stake. Buying the team was Tom Hicks, a successful equity investor who went all in on sports; besides the Rangers, he already owned hockey’s Dallas Stars and, later, the English soccer powerhouse Liverpool F.C. He wasn’t terribly smart about making baseball moves; though his acquisition of Alex Rodriguez in 2001 greatly enhanced the team’s marquee value, the record-shattering annual salary of $25 million paid to the megastar crimped a mid-market payroll and made it tough to build a team around him. Worse was his free agent signing of pitcher Chan Ho Park, whose five-year, $65 million deal yielded a 22-23 record and abysmal 5.79 earned run average. Under Hicks’ reign, the Rangers spent most of their time trying to reach .500, with little success. Seasonal attendance, which had flirted with three million back in the winning days of the late 1990s, skewed toward a more ordinary two million during the 2000s.

Hicks’ off-the-field efforts mirrored that of his team’s below-par results in the standings. He attempted to jumpstart development around the ballpark in 2000, proposing an ambitious, adjacent mixed-use complex of hotels, shops and restaurants, but it never got past the drawing stage. In 2004, Hicks chased extra revenue by signing a $75 million naming-rights deal for the ballpark with subprime mortgage lender Ameriquest. Part of the deal included the insertion of a 15-foot-high “Ameriquest Bell” (inspired by its logo) behind the left-field bleachers which rang whenever a Rangers player scored. The deal was to last 30 years, but it never got past three; Ameriquest became an early failure of the coming American mortgage crisis and folded, giving the Rangers no other option but to void the deal. They quickly renamed the facility Rangers Ballpark in Arlington.

First-row railings have been raised several times at Globe Life Park, a response to a number of incidents resulting in fan injuries (and, in one case, a death) after leaning out too far and falling below.

Happiness, and Sadness.

Hicks would soon go the way of Ameriquest. His business debts began to pile high, and things got so bad that by 2009, MLB began floating him money just to meet payroll. Bankrupt a year later, Hicks sold the Rangers after a lengthy and legally exhaustive process to a group co-led by Nolan Ryan. The news overjoyed Rangers fans, nostalgically connected to the Hall-of-Fame pitcher who seemed more content (and effective) than ever during his twilight tenure with Texas. As a bonus, Ryan and Co. had been handed a roster on the rise—with evolving stars in Josh Hamilton, Elvis Andrus, Nelson Cruz and closer-turned-starter C.J. Wilson; not standing pat, they continued to build, bringing in ace pitcher Cliff Lee midway through 2010 and third baseman Adrian Beltre a year later.

This all led to the Rangers brushing several monkeys off their backs: The taking of their first divisional title in 11 years, their first-ever postseason series win (over Tampa Bay in the 2010 ALDS) and, most blissfully, their very first pennant by finally toppling the New York Yankees—the thorn in their playoff side throughout the 1990s—in a six-game ALCS that included their first-ever playoff win at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington after seven losses. They lost the 2010 World Series in five games against San Francisco, but the fans and players, using a ‘we’re just happy to be here’ attitude, were filled with hope of a brighter future. That nearly came to full fruition the following year when the Rangers repeated as AL champions—but lost the World Series in far more heartbreaking fashion, pinning the Cardinals down to their last strike of the series twice before losing Game Six and, with less drama, Game Seven at St. Louis.

The back-to-back pennants revitalized the turnstiles at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington as the team jumped over the three-million mark in attendance for the first time. By 2013, a local poll revealed that the Rangers were even more popular than the holy Dallas Cowboys, who had made their own move to Arlington a few blocks to the southwest at AT&T Stadium—a massive, modern, UFO mothership of a stadium that made the Rangers’ ballpark look like a small provincial fortress by comparison.

The revised spirit at Rangers Ballpark in Arlington during these pennant-winning years was severely dampened by the curse of falling fans. During a game in July 2010, a firefighter named Tyler Morris reached out for a foul ball from his first-row seat in the second level down the first-base line; he reached out too far and fell to the field level below. The game was halted for 16 minutes while medics attended to Morris, who suffered a skull fracture and sprained ankle. Like Holly Minter back in 1994, Morris at least lived to tell about it.

Sadly, the same could not be said for Shannon Stone, another firefighter. A year and a day after Morris’ tumble, Stone was seated in the left-field bleachers with his six-year-old son during a game between the Rangers and Oakland A’s. A foul ball hit down the left-field line had ricocheted to Josh Hamilton, playing left for Texas. Hamilton innocuously lobbed the ball toward Stone, who had to reach outward to grab the ball—and his momentum led him completely over the railing and down 20 feet below, behind the left-field scoreboard. The game played on because the injury scene was out of sight from most of the 35,000 fans and the players, though a frazzled Hamilton couldn’t tune out the screams of Stone’s distraught son behind him. Stone was initially alert enough to ask about his son—but on the way to the hospital, in an ambulance joined by a deeply concerned Nolan Ryan, he went into cardiac arrest and died.

Both Ryan and Hamilton were heartsick over Stone’s death, and the Rangers went out of their way to console the grieving son and widow. They set up a memorial fund, which after a few months had already reached $150,000 (partly through team donations), and memorialized Stone with a statue of him holding hands with his son, located in front of the home plate entrance. They also raised the height of the railings yet again. Still, some cynical bloggers/journalists criticized the Rangers for doing ‘just enough’ to avoid a major lawsuit.

A statue of legendary ex-Rangers pitcher (and ex-co-owner) Nolan Ryan anchors the Bowtie Plaza, a food court behind center field.

A Little Here, A Little There.

Not much changed after Globe Life Park opened as the Ballpark in Arlington in 1994. The exterior remained the same, with its steer heads, lone stars and Sunset Red granite quarried from Marble Falls (near Austin) soaking up the Texan sun. The baseball lamps that adorn the outer edge of the upper deck concourse still brightened up the evening sky. The field dimensions weren’t altered, and foul territory was as microscopic as ever.

Beyond the renaming of things (ballpark, lounges, et al) owing to contractual obligations among sponsors, the more physical changes within Globe Park took place behind the outfield wall. The visitors’ bullpen, originally wedged in between the left-field bleachers and the main field level, was repositioned after 2011 to run parallel with the left-center field wall, knocking out a good chunk of bleacher seats. The official reason for the move was to make it easier for bullpen coaches to communicate with the dugout after a snafu during the 2011 World Series led to the wrong reliever entering the game for the St. Louis Cardinals. But one has to consider if the removal of the physical memory of Shannon Stone’s death, less than a year earlier, had something to do with it as well.

More intensive changes took place behind the center-field wall and the grassy knoll, er, incline, off limits except when invaded by home run ballhawks and the “Six Shooter” flag girls who paraded back and forth across it carrying giant Texan flags. Named Greene’s Hill after the mayor who championed the ballpark, the incline was initially backed by a dark green wall bookended by brick red towers topped by green spires as a batter’s eye to hide fan activity in the concourse and family play area behind it. But in the name of revenue, the Rangers in 2012 replaced the batter’s eye with the Hyundai Club, a 100-seat restaurant/lounge with four terraced rows looking out upon the field. Its dark, heavily tinted windows tempered the incoming heat while keeping hitters on the outside from being distracted. Behind the club was a food court area anchored by a statue of Nolan Ryan tipping his hat to the crowd because, who else could possibly get the first honor of being honored in bronze at Arlington? Actually, the answer to that question is Tom Vandergriff, the Arlington mayor who back in the 1960s made an aggressive (and, ultimately, successful) push to bring MLB to town. Vandergriff’s sculpture was relatively hidden within sight of Ryan’s, but hard not to notice for fans entering through the southeast gate as they’re basically welcomed by his likeness.

Behind the lower level of the Home Run Porch lay the Texas Rangers Baseball Hall of Fame, which was a great place to go—at first, anyway. It was once called the Legends of the Game Baseball Museum, a virtual Cooperstown with two stories’ worth of artifacts—a permanent exhibit on one floor, with more “roadshow” collections above; the third floor housed an interactive baseball learning center for children. “It was a godsend for kids,” said Globe Life Park tour guide Darwin Day, adding that the museum was open year-round and popular with local schools who arranged field trips for their students. But sometime during the regime change that ushered out Tom Hicks and brought in Nolan Ryan, the museum was rebranded and repurposed as a convention-type hall for groups to hold functions. Day asked why; the Rangers told him that although the museum wasn’t losing money, the team simply “wasn’t in the museum business.” Rangers-specific displays from the museum remain, but they became nothing more than historical bling on the wall amid a whole lot of open floor space—and paying fans usually couldn’t even see that unless they were part of a group renting out the Hall.

Throw Us Some Shade.

Folks doing their homework before attending a game at Globe Life Park usually came to the same conclusion: Don’t sit down the left-field line, and don’t sit in the bleachers behind left field. Because you were likely to get roasted.

“I like Globe Life Park,” said Dallas Morning News reporter Loyd Brumfield, “but the heat keeps me from loving it.” Brumfield’s muted praise can be traced to a single event: The time he, his girlfriend and her family went to a Sunday night game in July. The tickets were cheap—and situated mid-level near the left-field foul pole, right in the aim of the setting sun that still broiled with a first-pitch temperature of 106. “I could feel my skin sizzling for the first three innings until the sun mercifully sank behind the home plate seats,” Brumfield recalled.

There was only one thing worse for fans attending a Rangers game on a hot evening: Attending a Rangers game on a hot afternoon. Ideally, the Rangers avoided 1:00 starting times at Globe Life Park from June to September, but in an era when teams began avoiding graveyard-shift travel while bowing to national TV demands, they had no choice but to occasionally schedule midday games at Globe Life Park. “After May 11, the Rangers will have played 11 afternoon games at home,” wrote Mac Engel of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 2015. “That’s 11 too many.”

The Rangers agreed. They figured that when the mercury topped 100 degrees—as it almost always does in Arlington during the summer—day game attendance dipped by 8-10,000. Besides the lost revenue, the Rangers had to pony up to bring extra medics to look after those that arrived to Globe Life Park when it got really hot.

One way to beat the heat was to simply put a roof over the joint. Of course, that was easier—and more inexpensively—said than done. In 2008, the Rangers hired a German company to look into putting a sunscreen over the playing field. The firm postulated that a cover would lower temperatures within the ballpark by as much as 15 degrees—still quite warm on a hot summer day, yet at least tolerable. But the Rangers balked at the $100 million tag. “I’ve got mixed feelings,” thought Darwin Day about putting a lid on Globe Life Park. “For me, ballparks shouldn’t be enclosed—but you’ve got August.”

Alas, the hot sun would prove to be Globe Life Park’s undoing.

The white ornamentation fronting Globe Life Park’s third-deck overhang is said to be derived from Yankee Stadium, minus some of the elegance.

The End? This Early?

On May 20, 2016, the Rangers held a joint press conference with the City of Arlington to announce some stunning news: They were going to build a new ballpark, just to the south of Globe Life Park. It wasn’t that Globe Life was crumbling, out-of-style or outmoded; it was simply too overheated. They needed something with a roof, to accommodate the wellbeing of both fans and players. Six months later, Arlington’s voters—again declaring their pro-entertainment bias—agreed. With a 60% approval, the city was given the green light to build Globe Life Field, completed for $1.1 billion in 2020.

The irony is that as the new ballpark was being announced, the Rangers finally made headway on the massive development outside of Globe Life Park that the team had stripped gears for over 20 years trying to create. Texas Live!, a $250 million “entertainment village” that would include retail, restaurants and a splashy Loew’s hotel, broke ground in 2017 and will serve as a chic pre- and postgame conduit for Rangers fans. Globe Life Park barely got to enjoy the spoils of Texas Live! for barely a year before it closed down and the Rangers jumped across the street to Globe Life Field.

The question became: What was to happen to Globe Life Park, still theoretically in its prime? At first, all sorts of ideas were thrown out: Parking, residential units, retail, more office space—maybe even a museum. Ultimately, it conceded not to alternative usage or demolition experts but to sports such as football and soccer, with local teams ready to inherit a venue modified for more horizontally-shaped action.

Globe Life Park was meant to last 100 years according to Tom Schieffer back when it opened in 1994. But as a ballpark it didn’t even make it to 30. Instead, it served as a noble link between the ancient past (Arlington Stadium) and the cutting-edge future (Globe Life Field). In that role, it did quite well. The fans never soured on it even in spite of the heat, and it was said to be a money-maker not only for the Rangers but for Arlington, with annual revenue directly related to Rangers games amounting to nearly $100 million through hotels, restaurants, etc.

With the new yard open across the street, people will still walk past the Texas-inspired edifice of the old one and see the historical murals, steer heads and lone stars that still grace the building. They’ll remember that Globe Life Park, with all its faults, had true character—a strong pulse of being, a loud celebration merging the Lone Star State and this great game of baseball.

“It’s a perfect a place, it’s home,” lamented Darwin Day about the ballpark he gave tours to for over a decade. “We’re going to miss it. It’s a joy.”

The Ballparks: Arlington Stadium Somewhere deep in the heat of Texas, within the hyphen that separates Dallas and Fort Worth, the Texas Rangers played ball at an overgrown minor league ballpark that featured a plethora of bleacher seats but little else—especially shade for the searing sun and sudden downpours. Located next to Six Flags, Arlington Stadium was never able to hoist that seventh flag, but served as the jerry-rigged precursor for better venues to come.

The Ballparks: Arlington Stadium Somewhere deep in the heat of Texas, within the hyphen that separates Dallas and Fort Worth, the Texas Rangers played ball at an overgrown minor league ballpark that featured a plethora of bleacher seats but little else—especially shade for the searing sun and sudden downpours. Located next to Six Flags, Arlington Stadium was never able to hoist that seventh flag, but served as the jerry-rigged precursor for better venues to come.

Texas Rangers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Rangers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.