ED ATTANASIO, 1958-2023

Goodbye, My Good Friend

Interviewer. Writer. Artist. Comic. Knucklehead. Ed Attanasio was all of these things and more.

If all dogs really do go to heaven, then Ed Attanasio will be the happiest man there. His love for animals was, perhaps, only exceeded by his love for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

By Eric Gouldsberry, This Great Game

When I first met Ed Attanasio back in 1995, I immediately sensed a man who was determined to be the life of the party, the center of everyone’s universe. His presence was unavoidable, yet irresistible. Ed didn’t stroke his own ego at the expense of others; he welcomed everyone into his orbit like family, asking for nothing in return—except, maybe, that you allow him to remain the funniest guy in the room. With his effusive, practically nonstop sense of humor, sprinkled with an occasional dash of political incorrectness, that would be no problem.

My friendship with Ed was, at first, built around baseball. He knew that I had been working on an ambitious coffee table book on the history of Major League Baseball in the 20th Century, and I eventually discovered that he had been interviewing ex-ballplayers for SABR (Society for American Baseball Research). What a great idea it would be, Ed thought, if we could merge his interviews with all the content I had written for the book and put it together on a web site. Sure, I thought—but what would we call it? How about thisgreatgame.com, he answered, because it sounded great and, besides, he had already bought the domain and had yet to do anything with it. And with that, This Great Game was born.

Over the next few years, Ed and I evolved from business partners to true friends. It didn’t matter if he bled Dodger Blue while I loyally supported my Giants. We got to the point that This Great Game usually became a backend discussion in our hilarious chats—whether by phone or in person, usually at Friday lunch with our extended circle of friends at the late great Hawgs Restaurant in Campbell, California. Ed never tired of talking, and I never tired of hearing him—that’s how entertaining he could be.

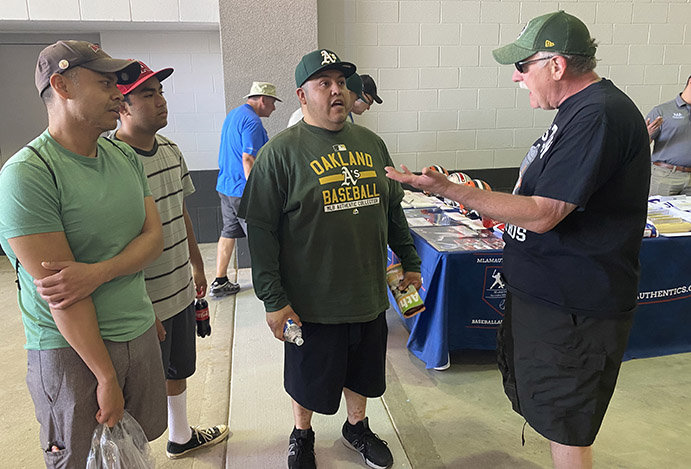

Proudly displaying a T-shirt to show his disdain for the infamous 2017 champion Astros, Ed poses with all-time A’s hit leader Bert Campaneris. Ed interviewed over 100 ex-ballplayers; his chat with Campaneris and many others live on in This Great Game’s Interviews section.

If anyone ever asked who would be the one person I would travel across the country in a car with, I would say Ed, without hesitation. I got that chance a couple of times, motoring with him from the San Francisco Bay Area to Los Angeles in 2015 (to check out Dodger Stadium and Angel Stadium) and to Phoenix right before the pandemic hit and closed down Spring Training in 2020. The long road traveled felt so much shorter because of his gregarious conversation and stories, for which he had a ton. Were they all true? Probably not. Were they fun to listen to? Absolutely.

The ultimate extrovert, Ed had an amazing gift for walking up to complete strangers and starting friendly conversations with them. Whenever we went to a ballgame and he got up to get a hotdog or something, I knew he wouldn’t be back for at least 30 minutes—because chances are, he’d run into someone, anyone, start up a casual conversation and win them over with his gregarious, chummy wit. That approach worked with the 100 big-league ballplayers he interviewed; rather than just be another talking head doing basic Q&A, Ed would use his folksy charm to warm up to them, loosening and breaking down any habitual defenses they might have had.

One of my favorite stories that summed up Ed’s sociable abilities to a tee was the one he told of the time he interviewed famed impressionist Rich Little for the Marina Times, a local San Francisco newspaper he wrote for circa 2010. Getting celebrities like Little to do interviews for small papers was like pulling teeth, and Ed knew there would be initial brushback. But he got the interview, and a few days later Ed received a call from Little’s assistant. “What did you do?” she asked Ed, who frantically began searching his memory for something horrible he may have blurted out during the chat. She continued, telling him that Little was ecstatic about the conversation and thought Ed was one of the best interviewers he had ever sat down with.

Ed craved the limelight and wasn’t afraid to sidle up to celebrities. In one trip to Vegas, Ed recounted how he had bumped into Spike Lee, the singer Jewel, and Roger Clemens—for whom he handed a TGG business card to. He once found himself at the same airport gate as Bob Costas and started up a chat with the broadcaster, who showed him the Mickey Mantle card he always claimed to have in his wallet. Another time while living in San Francisco, Ed caught the Giants’ Tim Lincecum hanging out at a local Starbucks, sniffing a scent of weed upon the star pitcher and realizing it wasn’t his own. (Yes, Ed was a “medicinal” user.)

Ed had a special gift for walking up to total strangers and starting a friendly chat. Here he shoots the breeze with a group of A’s fans he just met at a Spring Training game.

In the first 10 years I got to know Ed, he lived large—literally (he weighed 350 pounds) and figuratively. He did the occasional toke. He drank. He hosted parties, some of which recalled Animal House. There were wild excursions to Mexico with his college pals. Once, he arranged for a stripper to perform at a luxury box at a San Jose Sharks hockey game, causing a bit of a stir as you might imagine. Yet stepping away from the edge, Ed—a part-time comic who went by the stage name of Jaime Laredo—contained a very charitable side; he was the driving force in staging a night of local stand-up comedy and music every holiday season called Yuletide Yuckfest, with proceeds and gifts brought by audience members going to Toys for Tots.

The high times ended for Ed in August 2009 when, as his 51st birthday neared, he suffered a stroke. It wasn’t the debilitating kind; though he had moments of foggy memory, his speech and other senses remained intact and he did not appear handicapped to others. But Ed knew he couldn’t live in overdrive any longer. Diligently, he set about getting into the best shape of his life, swimming routinely and walking the steep streets of San Francisco. As a result, the pounds flew off. Ed remained a buoyant presence, but he had mellowed, wisely tempering his energy from the unbound, chain reaction-like excess of his pre-stroke days.

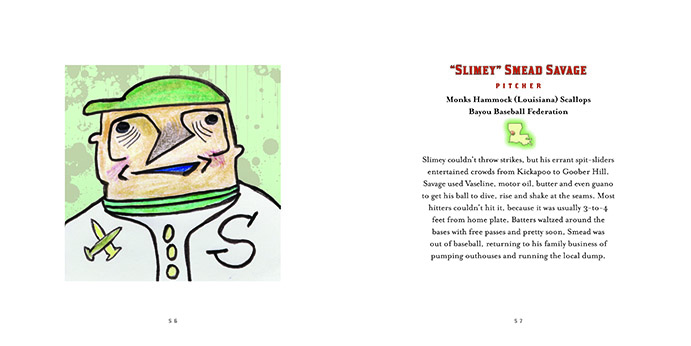

One of the revelations of Ed’s stroke therapy was his discovery of a highly unique artistic talent. Told to draw as a way to help “unscramble” his brain, Ed took out a bunch of colored pencils and began sketching inventive portraits of people and animals on Post-It Notes. He didn’t think much of keeping them and began chucking them in the trash, but his wife rescued them and put together a scrapbook to present to him as a gallery of his creations. This sparked Ed to consider a career in art, and his massive collage of 48 fictional Post-It characters drawn from baseball’s Deadball Era—“Bushers,” he called them—was framed and sold for $3,000 at an annual baseball art show exhibition in San Francisco entitled The Art of Baseball. “Bushers” took on an extended life when he gave the characters their own humorous bios and put them in a book entitled Bushers: Ballplayers Drawn From Left Field, which I helped him write, design and produce.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, Ed took his charity tact to the max by starting up the Pandemic Pet Project, in which he used his distinctive artisan touch to draw up portraitures of pets sent in by their owners who received the Post-It art in exchange for a donation of $50 (give or take a few bucks) to a pet rescue operation of their choosing. The requests came flooding in; day and night, Ed drew—and two years later, he had sent out some 3,000 illustrations to people in over 25 countries, bringing in $166,000 in donations. The effort drew national attention; Ed made appearances from the Today morning program (which labeled him “Post-It Picasso”) to Live with Kelly and Ryan to the BYU Network, proving that Ed’s sometimes edgy personality appealed even to Mormons. Those blessed with Ed’s art included Ellen DeGeneres, Val Kilmer, Rachael Ray, Lisa Vanderpump and Beth Stern (Howard’s wife).

I felt concerned that Ed was exhausting himself from the Pandemic Pet Project and asked him whether he had overcommitted to the endeavor. In listening to his response, I realized that, for Ed, the love of the effort trumped the labor involved, recalling my early days burning the midnight oil to happily produce all that content for what would eventually be This Great Game. Being the practical and introverted antithetical to Ed, I occasionally pressed him to make the most of his talent and monetize the art wherever possible so he wouldn’t have to go scrambling for more copywriting work that had dwindled during the pandemic. But Ed never truly sought that approach—an ironic notion, given that he once wrote for Thomas Kinkade, arguably the most capitalist of artists.

Ed didn’t stop with the Pandemic Pet Project. He also hooked up with former media executive Ron King to help do public relations and draw up more art for Oscar’s Place, a Northern California-based sanctuary for rescued donkeys. Among those receiving his art were donkey ‘guardians’ Arnold Schwarzenegger and Martha Stewart.

All along, Ed still had time for baseball. He continued to bleed for his Dodgers as he bled for his pet dogs, the only true children of his life. We’d still catch a game or two every year, talking whatever and chilling out to the glorious sights and sounds of this great game. But in the last few years, it was apparent that Ed’s batteries were starting to run low; he had gone through divorce, found paid work harder to come by, and now his heart was starting to hiccup on him, beating irregularly and leaving him physically spent. Doctors whose jobs it was to help him dragged their feet, bureaucracy in the health industry being what it is.

Still, Ed kept interviewing ex-ballplayers, and he wanted to keep drawing. With the pandemic over, he asked me to update the Pandemic Pet Project logo to its new brand—the Perpetual Pet Project, or as we discussed, PerPETual Project. Of course I would, as I always told him—anything for a good and loyal friend.

A spread from Bushers, a book featuring Ed’s unique Post-It art. Ed began drawing these unusual portraits as therapy following a stroke in 2009.

On the afternoon of July 18, 2023, I was working on the first draft of the revised logo, and felt happy enough with its progress that I was ready to save the file and email it for his approval. Little did I realize that, roughly at the same moment, I had received a call from Ed’s brother Gino. Because my mobile was on silent, I missed the call, but when I caught the transcript to Gino’s voicemail, saying that he had “some unfortunate news,” I knew what had happened. Even before I called Gino back, the heart had already sunk, the shock already set in. My colleague, my pal, my source for laughter, was gone.

It doesn’t seem right that Ed’s heart gave out on him when he had so much of it. He left behind too many friends, too many fellow baseball historians, and too many strangers he quickly converted into friends. For many of those people, Ed’s elvish yet gentle spirit will remain etched within their souls. For the thousands of people who were gifted with his art but never got the chance to meet him, his spirit remains in the pet drawings he tirelessly—and happily—sketched out for them.

For me, when I do my next lonely long drive to a distant press check or faraway rendezvous with my daughter to help her move to her next National Forest Service job, the passenger seat will be saved for Ed’s ghost, or spirit, or post-life energy mass. The conversation will be lively, engaging and hysterical as always. And the miles will go by more quickly.