THE YEARLY READER

2006: Two Reluctant Enemies

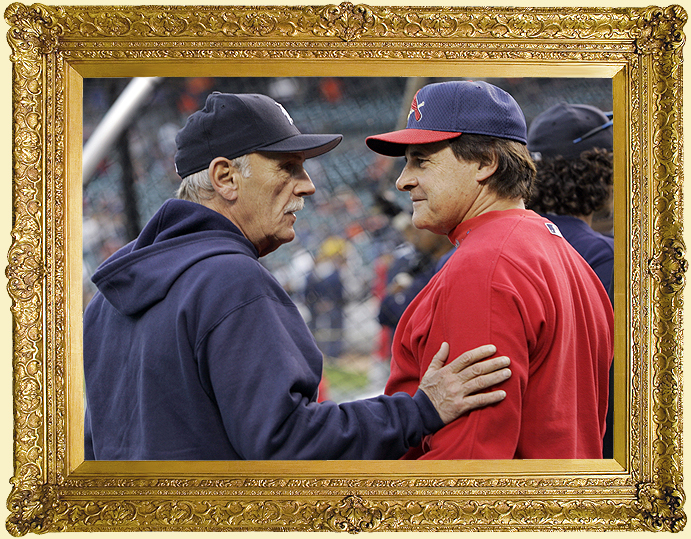

Best of friends, veteran managers Tony La Russa and Jim Leyland overcome various stigmas to win league pennants—and find themselves facing each other in the World Series.

Managers Jim Leyland (left) and Tony La Russa engage in a friendly chat before taking on one another in the World Series. (Associated Press)

It was Game Two of the 2006 World Series, and Detroit Tigers pitcher Kenny Rogers was caught red-handed. Or pine-palmed.

In the opposing dugout, St. Louis Cardinal manager Tony La Russa had been alerted moments earlier that TV cameras had zoomed in on Rogers’ palm just below his left thumb and noticed an umber-like smudge which looked suspiciously like pine tar—a substance pitchers were disallowed to use.

The situation had smoking gun written all over it, and when La Russa went out to talk with the umpiring crew before the second inning, chances looked good that Rogers would be served with one of baseball’s most historic ejections.

But instead, La Russa asked the umpires to check Rogers out, have him clean up whatever it was, and move on. No confrontations, no ejections. And that’s exactly what the umpires did.

Outsiders were puzzled how La Russa, a veteran competitor with a knack for playing the bulldog inside the ballpark, would have given Rogers a relative pass—especially during the World Series. Speculation arose that La Russa would play it light to avoid straining a relationship with his best friend: Jim Leyland, the opposing manager in the Tigers’ dugout.

La Russa’s handling of the Rogers issue would serve him well, jeopardizing neither his solid friendship with Leyland nor his chances of steering the Cardinals to their first Fall Classic triumph in 24 years.

To those outside of St. Louis, it seemed odd that Tony La Russa had yet to be fully embraced by the large and loyal Cardinal Nation. Here was a man who was now third on the all-time list of managerial wins. Here was a man who helmed his teams to 12 postseason appearances over 28 years—including six of seven seasons with St. Louis during the 2000s. Here was a man acclaimed enough to be endeared by Hollywood, which began prepping up a film adaptation (never realized) of Three Nights In August, the popular book in which La Russa’s life on and off the job is profiled.

For St. Louisians, struggling to come to terms with La Russa may have stemmed from the fact that he followed two popular Cardinal figures in Whitey Herzog and Joe Torre as manager. Or that he relegated the beloved Ozzie Smith to the bench. Or that he still called California his home. Or perhaps it came from an intense, humorless disposition that, to observers from the edge, gave him that look of someone in desperate need of the nearest outhouse. But La Russa’s positives—his winning ways, his thorough inside-and-out knowledge of the game, his absolute loyalty to his players—were enough to reduce the other issues to sidebar status at best.

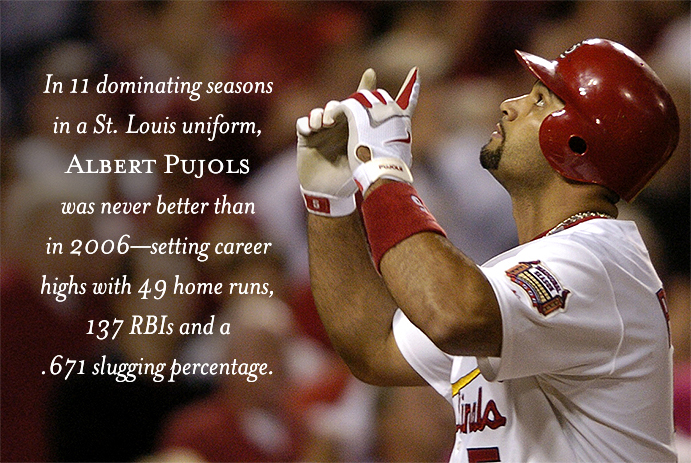

Such trivial negatives seemed moot as the Cardinals got off to a hot start in 2006. La Russa, with pitching coach and trusty lieutenant Dave Duncan at his side, was getting soaring results from a starting rotation of Mark Mulder, Jeff Suppan, Jason Marquis and reigning NL Cy Young Award winner Chris Carpenter. Albert Pujols, arguably the game’s most feared hitter, was rocking and socking baseballs out of the park to the tune of 25 homers and 64 RBIs by the end of May. There was not an empty seat to be found at the Cardinals’ brand new, retro version of Busch Stadium. Life was good.

(Associated Press)

On June 23, the Cardinals, four games atop the National League’s Central Division, flew into Detroit for the start of a three-game interleague series with the Tigers. For one of the rare times since he began managing, La Russa would be matching wits against his good pal, Jim Leyland.

The friendship between La Russa and Leyland went back to 1982, when La Russa—in his fourth year managing the Chicago White Sox—brought Leyland onto his coaching staff. Leyland seemed chiseled from the same clay as La Russa: No-nonsense, loyal and knowledgeable on the subject of baseball. Eventually the two parted ways on the field—La Russa to Oakland, Leyland to Pittsburgh—but their bond to one another remained strong, always calling one another, always talking baseball, often in the middle of the night.

Like La Russa, Leyland had something to prove as well in 2006. But whereas La Russa was trying to meet sky-high expectations to win over the hearts and souls of Cardinal fans, Leyland was simply trying to prove he had enough heart and soul left to manage, period.

After his successes a decade earlier with a low-budget roster in Pittsburgh—followed by a world championship with Florida, in 1997—the fire seemed to fizzle out in Leyland’s belly. He grudgingly presided over a hopeless 1998 Marlins team gutted out by a fire sale, then fled to Colorado—where he had an unremarkable one-year tenure dogged, he would later admit, by a lack of enthusiasm. It appeared that Leyland was fading out of baseball.

Following the disaster of Colorado, Leyland hooked back up with La Russa and served as a Cardinal scout for six years. During this time, Leyland rediscovered the urge to manage again. After 2005, he lobbied several teams who had openings at the helm, but after his ennui of the late 1990s, they were mostly skeptical—except one.

It had to be wondered who needed the other more: The dying-to-manage-again Leyland, or the Detroit Tigers. A storied franchise, the Tigers had long since fallen on hard times. They hadn’t finished above .500 in 12 years, became infamous for losing 119 games in 2003 and—despite a nice new downtown ballpark—were so financially beat up by 2005, rumors arose that the team was struggling to meet payroll.

Leyland’s arrival in Detroit, a homecoming of sorts, was considered a calculated risk. Could Leyland rekindle the fire within him? And even if he did, would it be enough to lift a franchise so ensconced in failure for over a decade? The answers were yes and yes.

BTW: Leyland spent the first 17 years of his pro baseball career in the Tigers organization—six as an unsuccessful catcher who never made it to the majors, 11 as a minor league manager.

A recharged Leyland scorched away the cobwebs of doubt in the Tiger clubhouse, instilling new life with well-timed fury. Ivan Rodriguez, the veteran all-star catcher with a reputation for testing managers, found this out the hard way when he challenged Leyland in the season’s first few weeks—and lost badly, as Barry Bonds had 15 years earlier when he tried to push Leyland in Pittsburgh. The rest of the team felt Leyland’s wrath in an angry, closed-door postgame tirade following a 10-2 loss to Cleveland that dropped the Tigers to 7-6. That record may have gone over well with Tiger players who had become accustomed to losing, but Leyland growled that they could be much better.

Much better the Tigers would become: They won 28 of their next 36 games. The secret was out, even for those within the Detroit clubhouse to discover: The Tigers were for real.

When Tony La Russa and the Cardinals came to Detroit in late June, he discovered just how real Leyland’s Tigers were; St. Louis was swept in three games. By then, being embarrassed by his best friend’s ballclub was the least of La Russa’s problems.

After their fast start, the Cardinals endured wave after wave of misfortune that threatened to derail their season. Their three-game sweep at Detroit was just part of an eight-game losing snap, one of many extended dips throughout the summer. An unraveling roster was part of the problem; Mark Mulder’s earned run average ballooned to 7.14 before he realized his rotator cuff had torn, while Jason Marquis, healthy so far as the doctors could see, lost 10 games after the all-star break, finished the season with a 6.02 ERA and thus was left off the postseason roster. Injuries and inconsistency plagued closer Jason Isringhausen (shut down with a bad hip in September) and much of Albert Pujols’ supporting cast, including sluggers Scott Rolen, Jim Edmonds and scrappy shortstop David Eckstein.

After overcoming all of the above, and with the NL Central title practically in the bag, the Cardinals—remembered for benefiting from the collapse of the 1964 Philadelphia Phillies—nearly lost it in much the same way. Leading by seven games with 13 to play, St. Louis reeled off another losing streak of seven and, combined with a nine-game win streak by the defending NL champ Houston Astros (buoyed by the midseason return of Roger Clemens, ending his latest retirement) had its lead shredded to a mere half game. But behind La Russa, the Cardinals persevered in the season’s final weekend and held the slim lead to capture the division.

Jim Leyland had it no easier in steering the Tigers through second-half difficulties in Detroit. After peaking impressively at 76-36, the Tigers began to suffer after an apparent season-ending shoulder injury to second baseman Placido Polanco—hardly a statistical powerhouse of a player, but highly valued in his teammates’ eyes as the glue of the team.

Without Polanco, the Tigers were 14-21. And then, out of nowhere, Polanco sprang up and said he was ready to play again, giving Detroit an emotional lift—if nothing else. Fighting it out in an extremely tough AL Central against the defending world champion White Sox and upstart Minnesota Twins, the Tigers struggled even with Polanco back, finishing the year with five straight losses—including three at home to lowly Kansas City—costing them the divisional title before salvaging the wild card spot.

BTW: The Twins won the AL Central over the Tigers by a single game; the White Sox, despite 90 wins, missed the postseason.

Leyland was able to forge outstanding efforts from rookies and reclamation projects alike. From the rookies, he got a 17-9 record and 3.63 ERA from powerful right-hander Justin Verlander and a 1.94 ERA from middle reliever Joel Zumaya, who reportedly threw the majors’ fastest pitch ever at 103 MPH; from the reclamation well, Leyland got 17 more wins from 41-year-old Kenny Rogers, who nobody else wanted a year after his pariah-like actions with the press in Texas, and Magglio Ordonez, a once-feared slugger who appeared permanently broken from injuries until suddenly revived in 2006 with a .298 average, 24 homers and 104 RBIs.

Opening the postseason opposite the almighty New York Yankees, Detroit lost the first game but then clamped down on the Bronx Bombers—holding them scoreless for 20 straight innings, the high-powered Yankees’ longest stretch without a run all year, over parts or whole of the next three games, all Tiger wins, to hand the Yankees a first-round playoff exit for the second straight season. Detroit then guaranteed its first World Series appearance in 22 years—and Leyland’s second of his managerial career—when it swept the Oakland A’s in the ALCS, adding a dramatic touch in the pennant clincher when Ordonez launched a three-run, ninth-inning homer to break a 3-3 tie in front of the hometown fans at Comerica Park.

Having survived the downside of his yo-yo regular season, Tony La Russa righted the Cardinals’ ship in time for the first round of the NL playoffs by taking care of San Diego, winners again of a weak NL West, for the second straight year. But the true test in the NLCS still lay ahead: Taking on the 97-65 New York Mets, holders of, easily, the league’s best record.

To the Mets—who easily dispensed of the wild card-winning Los Angeles Dodgers in the NLDS—the Cardinals looked no more imposing in what was supposed to be a continued cakewalk to the World Series. Under manager Willie Randolph, the Mets featured an awesome bat attack led by veterans Carlos Beltran (41 homers, 116 RBIs), Carlos Delgado (38, 114), and young infielders David Wright (26, 116) and Jose Reyes (.300 batting average, 122 runs scored, 17 triples, 19 homers and 64 steals). But by season’s end, an epidemic of bad calves infected the pitching rotation. One such injury ended the year for staff ace Pedro Martinez in September, and on the eve of the playoffs, veteran hurler Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez—who pitched well after a horrendous start with Arizona—was done for 2006 when he hurt his calf as a result of some simple jogging in the outfield.

The Mets’ mound injuries leveled the playing field for La Russa’s Cardinals, a state of affairs that held literally true as the two teams stayed knotted all the way through to the ninth inning of Game Seven in New York. That’s when two unlikely heroes tipped the balance for St. Louis. Catcher Yadier Molina, whose .216 batting average was the lowest among NL players with at least 400 at-bats, slammed a two-run home run to unlock a 1-1 tie, and in the bottom half of the inning, rookie Adam Wainwright—who was forced to inherit the closer role one month earlier after Jason Isringhausen’s injury—sweated out a bases-loaded jam to finish the 3-1 triumph and send the Cardinals on to the World Series.

BTW: Wainwright, a future ace starter, would save four games and toss 9 2/3 shutout innings during the 2006 postseason.

For best friends Tony La Russa and Jim Leyland, the golden chance to add another World Series title to their resume was at hand. But the uncomfortable part lay in the fact that one would have to beat the other to achieve the goal. All of the tireless, late-night phone conversations between the two came to a halt as Game One beckoned between the Cardinals and Tigers. At this pinnacle, performing head-on, there was a mutual understanding between the two that competition trumped not necessarily friendship, but certainly strategic gossip.

On the field, La Russa would discover that strategy itself would be trumped by fortuity, particularly in regards to the fate of the opposing pitching staffs. For Game One, La Russa chose to go with another rookie, Anthony Reyes, who pitched into the ninth inning for the first time in his big league career and helped the Cardinals start on top with an easy 7-2 win at Detroit. For Games Two and Five, La Russa crossed his fingers and put his trust into veteran Jeff Weaver, an early-season shipwreck in Anaheim before the Cardinals grabbed him off waivers and worked on his mechanics. The repairs were a success; Weaver finished the postseason with a 2.43 ERA and earned the victory in the Game Five, 4-2 win that iced the Series for St. Louis.

BTW: Weaver was released by the Angels—and his roster spot assumed by younger brother Jered, who won his first nine decisions to christen in a terrific career.

The Mighty Weakest

No World Series-winning team has had a worse regular season record than the 2006 St. Louis Cardinals, who top the below list of ballclubs who managed to take it all despite being outperformed during the year by more than a few other teams. Note that all of these winners played after 1969, when divisional play and multiple rounds of playoffs became the norm—allowing teams with inferior records to sneak into the postseason.

Jim Leyland watched in frustration as his own pitchers, while throwing well to the plate, threw wildly everywhere else. Detroit pitchers committed an error in each game, resulting in seven unearned runs; the last two miscues, in the Series’ last two games, erased Tiger leads that were never regained. Even the Tigers’ lone Series victory, a 3-1 triumph in Game Two, was nearly lost to glove botchery; after Kenny Rogers pitched eight shutout innings once he cleaned off whatever substance was on his throwing hand, closer Todd Jones muffed a grounder in the ninth that intensified a Cardinal rally that ended with one run in and the bases left loaded.

BTW: Rogers became the first pitcher since Christy Mathewson, 101 years earlier, to not allow a run in three starts over one postseason.

In the end, the 2006 campaign ended complacently for the two old friends. In finally winning it all at St. Louis—and becoming the second manager, after Sparky Anderson, to manage both an AL and NL team to a world title—La Russa at long last received wholehearted endearment from Cardinal fans. Leyland, despite defeat in the World Series, had proved not only his rejuvenated passion to manage but the success that it brought.

La Russa and Leyland continued their everlasting friendship after a week as foes, overcoming the discomfort of Kenny Rogers’ pine-toned palm that Rogers claimed as dirt and La Russa, tersely without emotion, claimed to be anything but. For La Russa and Leyland, two old warriors not known for their penchant to smile, “Smudgegate” was certain to bring some laughter out of the two once the phone calls resumed.

Forward to 2007: Bow if You Will, Spit if You Wish Barry Bonds breaks Hank Aaron’s fabled career home run mark, but few people are happy about it.

Forward to 2007: Bow if You Will, Spit if You Wish Barry Bonds breaks Hank Aaron’s fabled career home run mark, but few people are happy about it.

Back to 2005: At the End of the Primrose Path After years of looking the other way, baseball is publicaly forced to confront its dirty steroid laundry.

Back to 2005: At the End of the Primrose Path After years of looking the other way, baseball is publicaly forced to confront its dirty steroid laundry.

2006 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2006 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2006 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2006 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.