THE YEARLY READER

2008: Out of Darkness, Rays of Light

Thought to be eternally chained to the bottom of the AL East standings, the rebranded Tampa Bay Rays become one of the game’s unlikeliest surprise teams with a stunning appearance in the World Series alongside the Philadelphia Phillies.

Death and taxes have always been said to be the two certainties in life. And for a decade, baseball fans would tell you of a third: The order of finish in the American League’s Eastern Division.

From 1998-2007, parity had no meaning in the AL East. The only suspense was to which team, between the titanic New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox, would grab first place and leave the wild card to the other. Otherwise, the song painfully remained the same in the East. Toronto, a consistently competitive team standing in the shadows of the towering cash piles of New York and Boston, was a third-place constant. The Baltimore Orioles, struggling in the shadows of their former success, were entrenched in fourth.

And then there were the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

An expansion team in 1998, the Devil Rays were annually eliminated from postseason eligibility on Opening Day by the game’s pundits. Clad in uniforms with gradated tropical hues, the Devil Rays looked like a recreational retirement league team and played like one. They never threatened and, justifiably, were never taken seriously; the franchise was rumored to be on the chopping block when contraction talks hit the majors, and more recently suffered from serious cash flow issues. When the Devil Rays barely slipped out of the cellar and finished fourth in 2004, there was a champagne celebration in the clubhouse.

For 2008, Tampa Bay tried to shed its losing image aesthetically with a complete makeover, exercising the “Devil” from their name while introducing a new logo and uniform with a more traditional look and feel.

Almost no one anticipated that underneath the Rays’ improved façade lay a stunningly improved product on the field.

Hints of stability, if not improvement, began in 2005 when the team was taken over by Stuart Sternberg, who went about reducing the franchise’s red ink while forging a more intensive approach to building talent from within. To nurture that talent, Tampa Bay brought in as its new manager Joe Maddon, a baseball lifer in the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim organization who learned the deft yet stern approach to managing from his former boss in the dugout, Mike Scioscia.

BTW: Maddon had taken over for Lou Piniella, who bailed from the Devil Rays when he felt the team wasn’t committed to winning.

Despite the changes, Tampa Bay continued to be Tampa Bay for the next few years, flirting as always with 100 losses. In 2007, not only was there trouble on the field with another last place finish, the majors’ worst pitching staff and the AL’s second-worst defense, but there was trouble off it as Elijah Dukes and Delmon Young, two young, highly prized yet malcontented talents, created numerous distractions in the clubhouse.

The Rays shrewdly jettisoned Dukes and Young before 2008 in return for a blossoming starting pitcher (Matt Garza) and dependable shortstop (Jason Bartlett), trusted soldiers more willing to fit into the puzzle and make a contribution. For a franchise strapped with the majors’ second lowest payroll, the moves were seen as positive but also considered nothing more than baby steps on the long, long road to reaching competitive equality with the Yankees and Red Sox in baseball’s division of death. Experts believed the newly renamed Rays would do just well enough to break the franchise record for wins—hardly a difficult assignment, given that their previous high was 70; the oddsmakers were more skeptical, tagging the Rays as high as 400-1 underdogs to win the World Series.

Too inpatient to wait until the regular season, the Rays showed off their newfound, cohesive intensity to spring training opponents, engaging the Yankees in particular into several on-field brawls. Such testosterone elevated the Rays’ confidence, all while the Yankees waived them off as a low-budget wannabe trying to bully the master. But once the games began to count, the Rays translated their energy into a winning attitude by steadily hanging well over the .500 mark. And even as they were being swept by the Red Sox in an early June series at Fenway Park, the Rays left Boston with their heads held high after another scrap that further sharpened the Rays’ focus and support for one another—something badly lacking among the Devil Rays of old.

BTW: The fight at Fenway developed when Boston outfielder Coco Crisp reacted angrily to being hit by a pitch from the Rays’ James Shields.

As the season progressed, the Rays showed remarkable resilience for a team listed as the AL’s youngest. When they lost seven straight games going into the all-star break—giving the team unwanted time off to dwell on it—the Rays quickly rebounded to their winning ways when other inexperienced teams might have buckled under the pressure. When they did win, it was often in cardiac fashion; 11 games were won in their final at-bat, with stars and benchwarmers alike sharing in the heroics.

Despite the dramatics, despite the stunning about-face they exhibited from Opening Day, despite their constant placement in the AL East ahead of both the Red Sox and Yankees, fans in the St. Petersburg-Tampa area showed all the speed of a tortoise in jumping on the Rays’ bandwagon. Crowds at the Tropicana Dome remained as low as 12,000 through August; a three-game series against the Yankees after Labor Day averaged 24,000—15,000 below capacity—with many in the crowd rooting for New York. For much of the 2008 season, the only sellouts the Rays were able to achieve had less to do with baseball and more to do with postgame concerts featuring acts like Kool and the Gang and country star Trace Adkins. By season’s end, the Rays—Cinderella champions of the AL East with a 97-65 record—managed to draw just 1.78 million fans, ranking 26th among 30 major league teams.

BTW: Yankees and Red Sox fans typically outnumbered those of the Rays when their teams visited St. Petersburg; Red Sox fans in particular referred to the Tropicana Dome as “Fenway South.”

Nonstop to the Top at the Trop

Tampa Bay’s remarkable 31-game turnaround for the better fell just shy of making baseball’s top-five list for such achievements.

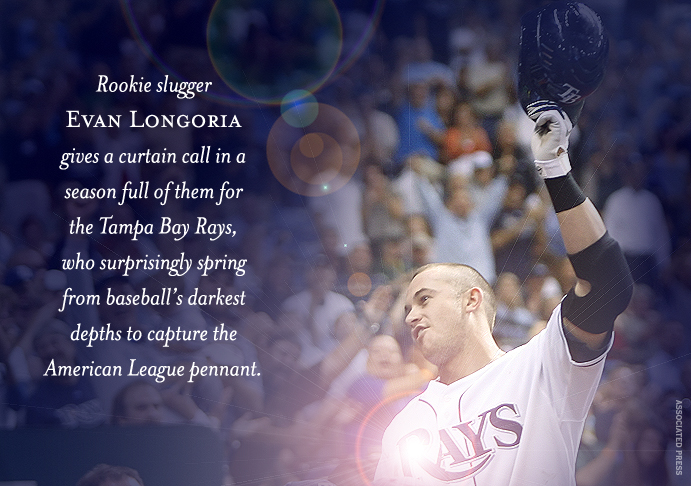

Offensively, the Rays were consistent if not overpowering, with first baseman Carlos Pena overcoming a slow start to lead the team with 31 home runs and 102 runs batted in; on the other side of the infield, highly touted rookie third baseman Evan Longoria hardly disappointed by adding 27 homers and 85 RBIs in just 122 games. On the mound, five starting pitchers (led by Garza, Scott Kazmir and James Shields) earned at least 10 wins while keeping their losses in the single-digit range, and the bullpen executed a spectacular turnaround, registering a 3.55 ERA after recording an atrocious 6.16 mark just a year earlier.

Any remaining skeptics who anticipated that the unaccustomed Rays would wilt in the heat of the postseason were won over. Tampa Bay had little problem taking care of an experienced Chicago White Sox team in the first round of the playoffs, leading to a date in the ALCS with divisional rival Boston, which entered October as a wild card. Now firmly in the national spotlight, the Rays initially shined for those who previously had not caught their act, taking three of the first four games against the high-priced defending champion Red Sox. But up 7-0 in the seventh inning of the potential Game Five clincher, the Rays blew all four tires as the Red Sox pulled off baseball’s biggest postseason comeback in 80 years to win 8-7 and stay alive. The shock and significance of that game threatened to ruin a season’s worth of momentum and vibe for the youthful Rays, but they slowly regrouped—and just in time, overcoming a Game Six loss to Boston back home in St. Petersburg with a hard-fought 3-1 win in the winner-take-all Game Seven. Tampa Bay in the World Series; it was a statement a lot of people took some serious getting used to.

As confident as the Rays had become, their opponents in the Fall Classic had long since run circles around them in the bragging department.

Even before spring training broke, the Philadelphia Phillies were feeling awfully good about their chances, and publicly so. Never mind that they were swept in the first round of the previous postseason after being granted a gift pass into October by the New York Mets, who collapsed in the home stretch. Bravado reigned supreme in Philadelphia, a state of mind best reflected in shortstop and reigning NL MVP Jimmy Rollins—who predicted that the Phillies would win 100 games in 2008.

Rollins’ prophecy appeared elusive throughout the year as, for the second straight September, the Phillies looked at the very real possibility that they would be home for October. But once more, the Mets came to their rescue. A year after botching a seven-game lead with less than three weeks to play, the Mets performed a mild encore, this time blowing a 3.5-game lead in the same time frame thanks to a wretched bullpen that blew one save opportunity after another in the wake of closer Billy Wagner’s season-ending injury in early August.

As much as the Mets deserved blame for their collapse, the Phillies deserved credit for waking up at the right moment and, once again, seizing the opportunity. Among those revived from a deep sleep were boomer Ryan Howard, slumping in the .220s through late August before destroying the competition with a .367 average and 12 homers over the Phillies’ final 27 games; ageless starting pitcher Jamie Moyer, who won his final six decisions to lead the Phillies in wins at age 45; and fellow starter and clubhouse leader Brett Myers, whose 7-4 record and 3.09 ERA in the final two months erased the bad memory of being temporarily sent to the minors after a terrible start.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the season in Philadelphia was the success of its bullpen, originally considered an iffy proposition once Brad Lidge, exiled from Houston after losing his touch, was named the Phillies’ closer. But Lidge re-emerged on the mound in perfect tune, converting all 41 of his save opportunities for the Phillies and, in sharp contrast to the Mets’ bullpen woes, may have been the major difference that helped send Philadelphia over the top, past the Mets and into the postseason.

Continuing their roll through October, the Phillies couldn’t be stopped by two NL playoff foes ignited by major midseason acquisitions. They couldn’t be stopped by the wild card Milwaukee Brewers, making their first postseason appearance in 26 years thanks to the second-half contribution of burly ace pitcher CC Sabathia, who survived a rotten start in Cleveland and became utterly dominant after being shipped to Wisconsin. Nor could Philadelphia be stopped, in the NLCS, by the NL West-winning Los Angeles Dodgers despite the presence of Manny Ramirez, the fickle veteran slugger who came west after purposely becoming a major distraction for the Red Sox in an attempt to get out; despite hitting .396 with 17 homers and 53 RBIs in 53 regular season games for the Dodgers—not to mention a .520 mark with four more jacks in the postseason—the Dodgers could only manage one win against the Phillies, who thrived on big innings and two stellar starts by third-year ace Cole Hamels to win the NL pennant.

BTW: Despite not making an appearance for Milwaukee until July 8, Sabathia managed to lead the NL with seven complete games and three shutouts.

Bad Manny, Good Manny

There was little doubt about Manny Ramirez’s ability to hit a baseball. Less certain was his ability to give a damn about it. For the unpredictable Ramirez, both abilities were on full-frontal display during 2008. Approaching the tail end of his long-term lucrative contract in Boston, Ramirez gradually showed off his dissatisfaction with the Red Sox in a bizarre chain of events that, by July, had him all but shouting to the world his intense desire to be traded. He engaged in one dugout brawl with teammate Kevin Youkilis in June, then another in Houston with the team’s 64-year old traveling secretary over a failure to provide a block of tickets. Ramirez also started complaining of a bad knee, a claim the Red Sox didn’t believe; when asked to get off the bench one night to pinch-hit in the ninth inning against the Yankees and Mariano Rivera, Ramirez walked to the plate and hardly budged as Rivera fired three strikes past him.

Ramirez told the press that the Red Sox “don’t deserve a player like me,” but by then his teammates were more than happy to see him go; 23 out of 24 polled by the media wanted Ramirez traded. Ramirez finally got his wish on August 1, when he was sent to Los Angeles as part of a three-team trade that netted the Red Sox Jason Bay from Pittsburgh. Like a liberated man on a mission, Ramirez’s game rocketed upward with the Dodgers, hitting nearly .400 with prodigious power, but his antics in Boston left him a pariah in the eyes of major league owners and general managers as free agency loomed.

All that now stood between the Phillies and their second-ever championship were the Tampa Bay Rays.

Fresh off their rollercoaster struggle against Boston, the Rays played the Phillies tight and split the first two games at St. Petersburg before crowds that were finally filling up the Tropicana Dome. Moving to cold and rainy Philadelphia, the Phillies crucially grabbed Game Three, responding to a patented late-inning Tampa Bay rally with an uprising of their own in the bottom of the ninth. Not that the Phillies had anything to do with it. The Rays’ J.P. Howell started the frame by hitting Eric Burntlett. Grant Balfour took over for Howell, but delivered a wild pitch past his first batter, Shane Victorino. The moment only got wilder when catcher Dioner Navarro, trying to nail Burntlett at second, threw wide into the outfield. With Bruntlett at third and no one out, the Rays intentionally walked the next two batters to set up a force at any base, but Carlos Ruiz tapped a slow grounder up the third base line that gave Bruntlett enough time to score ahead of Evan Longoria’s throw and win the game for Philadelphia, 5-4.

BTW: The Rays went to extremes after loading the bases by bringing in outfielder Ben Zobrist as a fifth infielder, but the tactic became moot.

The Rays’ feeling of deflation after handing the Phillies Game Three became magnified in Game Four when Ryan Howard’s two home runs powered Philadelphia to a 10-2 rout. Desperately hoping to avoid elimination and move the series back to Florida, the Rays in Game Five struggled along with the Phillies in miserably wet and windy conditions that forced umpires to call a halt in the sixth inning—just as the Rays had tied it at 2-2—ultimately making it the first World Series game ever to be suspended by bad weather. Unbeknownst to the players, Commissioner Bud Selig had earlier smelled the rain in the Philly air and set an agreement with management of both teams that any Series game would be played to a full conclusion, a departure of sorts from regular season contests. Two days after play stopped, Game Five was continued with a see-saw affair that ended in the Phillies’ favor, 4-3, to ice the Series.

From start to finish, Philadelphia pitchers became the primary heroes of the World Series. They neutralized the Rays’ two slugging stars of the AL playoffs, Evan Longoria and B.J. Upton, who against Chicago and Boston smacked a combined 13 homers; against the Phillies, the two ganged up to go 6-for-40 with no extra base hits. Among the chief contributors to Longoria and Upton’s hitting woes were Cole Hamels, who wrapped up a 4-0 postseason with two more solid starts against Tampa Bay, and Brad Lidge, who capped his year of perfection in the closer role by nailing down the Series clincher for his seventh postseason save—in his seventh opportunity.

BTW: Late in the World Series, Philadelphia fans began tormenting Longoria with chants of “Eva”—a reference to Eva Longoria, star of the then-hit TV series Desperate Housewives.

The Phillies’ Brad Lidge celebrates second after closing out the World Series to complete a perfect season in which he saved 48 games without blowing a single opportunity. (Associated Press)

For the Phillies, the preseason bragging paid off. Jimmy Rollins’ headline-making boast was realized; with 92 regular season wins and 11 more in the postseason, the Phillies got their 100 wins—and then some.

In spite of defeat, the Tampa Bay Rays, once destined to become baseball’s eternal losers, were given just as big a pat on the back for achieving what some believed was unthinkable. The Rays shook up the decade-long status quo in the wide-ranging class structures of the AL East and relegated the game’s marquee franchises, the Yankees and the Red Sox, to the back seats.

The bigger challenge lay ahead for the Rays: Avoiding the stigma pegged upon other small- to mid-budget one-shot wonders who briefly sprang loose in the 2000s. Because, and without a doubt, the Yankees and the Red Sox were not about to disappear.

Forward to 2009: The Salvation of Alex Rodriguez Baseball’s biggest star embarks on a long, tough road from injury and damning steroid evidence.

Forward to 2009: The Salvation of Alex Rodriguez Baseball’s biggest star embarks on a long, tough road from injury and damning steroid evidence.

Back to 2007: Bow if You Will, Spit if You Wish Barry Bonds breaks Hank Aaron’s fabled career home run mark, but few people are happy about it.

Back to 2007: Bow if You Will, Spit if You Wish Barry Bonds breaks Hank Aaron’s fabled career home run mark, but few people are happy about it.

2008 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2008 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2008 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2008 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.