THE BALLPARKS

Fenway Park

Boston, Massachusetts

(Flickr—Massachusetts Office of Tourism and Travel)

It’s crowded. It’s uncomfortable. It’s expensive. And it’s on everyone’s bucket list. With disharmonious angles, unpredictable caroms and wall heights ranging from a pesky three feet to a monstrously green 37, Fenway Park is baseball’s ultimate pinball machine, nearly unplugged more times than a cat has lives before its antiquity became too priceless to abandon. And always remember: When you enter, you’re not merely a spectator—you’re a participant. Have a great time.

Should anyone ever get around to publishing a dictionary on Fenway Park, one word will clearly be left out: Symmetry. Such an omission is understandable given the ballpark’s famed quirks, from the Green Monster to the Pesky Pole to Williamsburg. But the irregularities don’t stop at the foul lines and outfield walls. Walk around Fenway’s exterior and you’ll quickly discover that no two square feet are alike. Red brick bases of various heights dance with segments of exposed industrial green steel that rise, extend and retract at random angles. You know those mind-bending paintings of M.C. Escher, where one stairway rises only to connect at the top with another that you thought was two stories below? It’s kind of like that.

Fenway Park wasn’t designed, constructed and appended to be a funhouse for funhouse’s sake. Its eccentric layout is a reaction to a surrounding city grid no less chaotic, with streets slicing and intercepting about as if out of total civil disobedience. It would make a web-spinning spider spun dizzy.

But Fenway’s myriad of ancient asymmetry is its main attraction, why so many people write it down as one of 100 places they must see before they die and go to heaven. Fans inside marvel at the spectacular, up-close-and-personal sightlines—provided they’re not sitting behind a post—the voluminous, 37-foot-tall Green Monster that cuts into left field, the protruding bullpens in right-center where many outfielders have found themselves upended into, and a wrap-around right-field corner than bends and meets the foul line a mere 302 feet from home plate, the shortest distance to any pole in the majors.

The trick for anyone making the Fenway pilgrimage is just trying to get there. There is a freeway just a block to the north—actually it’s not free, it’s the Massachusetts Turnpike, which has plenty of toll booths but precious few exits, none of which drop you off near Fenway. If you’re lucky to find your way upon the streets around Fenway, you’ll be even luckier to find an available parking spot. As with all things Fenway, chaos rules.

It seems hard to believe now, but there was a time when Fenway Park was bad-mouthed for being outmoded and, worse, out of style—just another aging ballpark in a dilapidated part of town whose days appeared numbered. It’s kind of like the old rocker who once produced one chartbusting hit after another, only to become passé, unwanted and relegated to the $1.99 album clearance bin. But ultimately the retro value kicks in, and everything old is embraced again. And Fenway Park, like, say, A Flock of Seagulls, has become hip again—and the vibe has never been stronger at 4 Jersey Street.

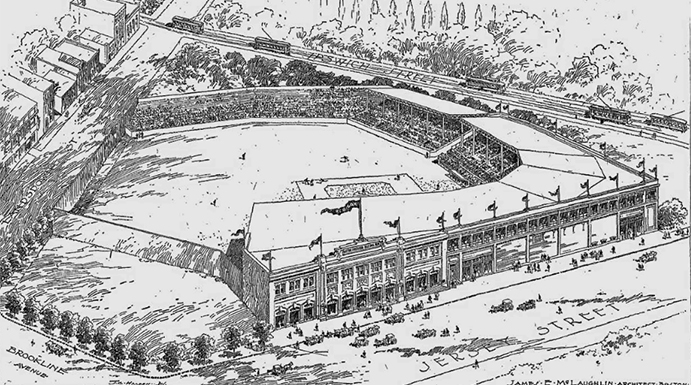

An aerial sketch from Fenway Park architect James McLaughin reveals the ballpark as visualized before its 1912 opening. Note the off-centered location of the formal entrance on the third-base side.

Taylor Made.

Long before Fenway Park, the Fens—as the area was called—was nothing more than a marshy expanse on the outskirts of Boston. In the late 1870s, an effort began to convert the swamp into viable parkland as part of a larger, ambitious parks project entitled the Emerald Necklace. Not all of the area was beautified, but it was landfilled and made habitable for residential and business development—with much of it bought by the Fenway Realty Company, owned by Boston Globe publisher Charles Taylor. The Taylors also owned something else: The Boston Red Sox, given to 29-year-old son John I. Taylor in 1904 as something of a plaything to keep him from getting bored with the family riches. The Red Sox—or the Americans, as they were called through 1907—played their infant years at Huntington Avenue Grounds, built on the cheap ($35,000) with barely 10,000 seats; the team somehow once managed to cram 36,000 through the gates to watch a doubleheader. Perhaps Taylor got them all to sit in a spacious outfield that measured 440 to left-center and, in 1908, an unbelievable 635 feet to the deepest part of center field.

Best known as the site of the very first World Series game (in 1903), Huntington Avenue Grounds was a rickety mass of wood, which meant that sooner or later it was going to catch fire; after all, nearly half of the other major league facilities built of lumber had. The younger Taylor, not exactly the most passionate baseball man, wanted to build the Red Sox a new ballpark—and then he wanted out. It just so happened that he had the Fenway Realty Company to lean on.

Available was a warped pentagonal plot of land, less than a mile west of Huntington Avenue Grounds, with borders defined by five surrounding streets and totaling 365,000 square feet. Critically, the space would be located near trolley lines to ferry fans in. Taylor’s master plan was to snag the land, build the ballpark, sell the team and make a fortune on the surrounding land that was sure to attract development once the Red Sox took root. Before he made good on his goal—selling controlling interest for $150,000 a month after the first shovels were dug into the ground—he made one last decision by naming the new ballpark Fenway Park. This may have seemed modest on the surface, given that other recently constructed steel-and-concrete ballparks were being named after the team owners who built them, but for Taylor it would all be about real estate—his real estate.

From the outside, Fenway Park lacked the palatial formality of Philadelphia’s Shibe Park and Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, the trendsetters of the steel-and-concrete movement. The venue’s central focus—and main entry—would be aimed not behind home plate but, instead, along the third-base side of the grandstand along Jersey Street, with a prudent façade embossed two feet outward and topped with a simple but dignified nameplate. The red brick facings, complimented with touches of warm, off-white concrete, would be a good representation of Fenway architect James McLaughlin’s larger body of (mostly local) work: Attractive but not exaggerative, in keeping with traditional New England aesthetics without pushing the envelope. Fenway would be a one-time opportunity for McLaughlin, whose bread-and-better work was focused on schools; his only other relative claim to aesthetic fame would be his design for the now-extinct Commonwealth Armory, adjacent to the also-now-extinct Braves Field a mile west of Fenway.

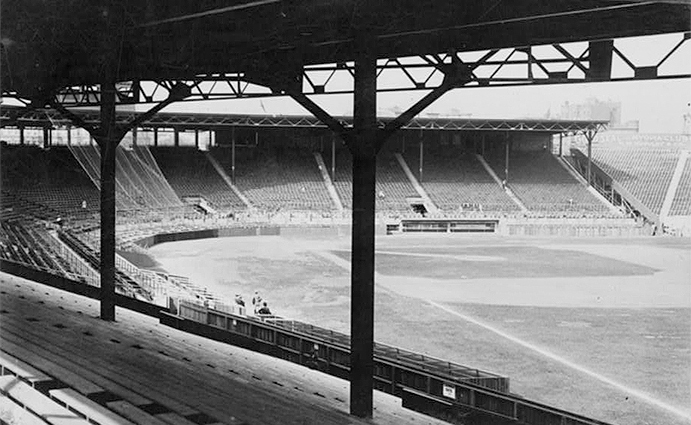

The interior of Fenway Park in 1914, two years after its opening. The wooden bleachers at far right were constructed toward the end of the 1912 season to accommodate larger crowds for the World Series—and burned to the ground in 1926. (Library of Congress)

Anyone familiar with today’s Fenway might have a harder time recognizing the place on the inside as initially constructed. The covered, single-deck grandstand—plans called for a second level, but they never got around to it—might look familiar, and while there was a separate bleacher structure (also roofed) angling down the right-field line, there was none to be found on the opposite side, past the end of the main grandstand at third base. This led to a wide-open expanse of foul territory, easily accessible by fielders chasing a foul ball—that is, if they could complete an exhaustively long sprint deep into the area to catch up to it. Beyond the outfield, uncovered bleachers took up a good chunk of land behind center, but another wide gap of open space dominated behind right, used as parking for the few autos making the trek to the new ballpark.

There would also be an early variant of the Green Monster, a 25-foot-tall wooden fence behind left field that continued all the way around the open area along the left-field line before connecting up with the back of the main grandstand. The fence seemed even taller because it was perched atop an incline that rolled down 10 feet at a 45-degree angle to the playing surface. The incline was hardly a gimmick; the road behind the wall, Lansdowne Street, was raised above ground level like most other streets in the area to act as a virtual levee against potential floodwaters from the nearby Charles River.

The incline would soon be forever known as Duffy’s Cliff, named after the one outfielder who seemed to master it: Duffy Lewis, the popular Red Sock who regularly patrolled Fenway’s left field from its 1912 debut through 1917. Most other left fielders, particularly those for the visiting team, fared far worse against the incline. In the early 1930s, the Detroit Tigers’ Bob “Fat” Fothergill, an all-hit, no-glove player pining for the future days of the designated hitter, managed to make it to the top of the cliff—then came a stumblin’ and tumblin’ down, all 230 pounds of him, like a rolling stone. Fothergill gathered no moss or sympathy from laughing Fenway fans.

This rough but revealing image of Fenway Park in 1918 shows the precursor to the Green Monster (smothered in ads) and the 10-foot incline known as Duffy’s Cliff that rises to its base. (The Rucker Archive)

Acing the First Take.

After hosting a “soft” opening on a snowy, early April day with a 2-0 exhibition victory over Harvard University, the Red Sox officially debuted Fenway over a week later. Or at least they tried. The first scheduled game, on April 18, was rained out. The next day, they tried a morning-afternoon doubleheader sandwiched around the Boston Marathon; both of those games were also squashed by wetness. Finally, a day later, both the skies and field were dry enough to give it a go, and the Red Sox pleased 27,000 patient fans—including Boston mayor John F. Fitzgerald, grandfather to future president John F. Kennedy, who threw out the ceremonial first pitch—by overcoming an early 5-1 deficit and defeating the New York Highlanders in 11 innings, 7-6. Tris Speaker knocked in the game-winning run, helping to overcome seven Red Sox errors that would be, in their first game at Fenway, as many as they’d ever commit in any home game since. Such zaniness at a brand new ballpark barely made a dent on the front pages of the local Boston newspapers, still obsessed with the sinking of the Titanic a week earlier.

It didn’t take long for Fenway Park to undergo its first expansion. That the Red Sox won 105 games in their first year at the ballpark had a lot to do with it. To welcome in bigger crowds for the ensuing World Series against the New York Giants, the Red Sox filled in the blanks around the field—quickly propping up massive bleacher structures down the left-field line and behind right field; additionally, temporary seating was put up on Duffy’s Cliff. Even the press box, perched atop the grandstand roof, was considerably widened to accommodate an influx of reporters. Capacity was increased by 10,000 to over 34,000—a figure that would roughly remain the Fenway standard to the present day—and fans filled the joint for all but the decisive game of the Fall Classic, when only half of the seats were filled as others stayed home out of solidarity (or so it’s told) for the Red Sox’ fabled Royal Rooters supporters group, which had been rudely denied their seats a day earlier. The no-shows missed quite a game; in a mirror-imaged performance of their Opening Day performance, the Red Sox trailed early, fought off a slew of errors (five), then rallied in extras, the opposing Giants obliging them through a comedy of gaffes highlighted by outfielder Fred Snodgrass’ famed “$30,000 Muff” to give the Red Sox their first of four world titles through the next seven seasons.

More building took place around the ballpark in the next few years to follow. The Red Sox made use of the expansive, triangular plot of land behind right field by building a parking garage (also designed by James McLaughlin) that housed 500 autos. And clear across the property behind the third base-side bleachers, a business structure filled in the remaining space trapped between Fenway Park and three streets—Lansdowne, Jersey and Brookline—that was built so close to the edge of the ballpark, it appeared to be part of it. (Years later, it would.) Auto dealerships initially took up the space, giving way in later years to radio and TV stations; by the 1950s, it became home to a bowling alley. By then, the Red Sox took over ownership of the building and gradually expanded its offices into the space. Today, the first floor of the Jeano Building—named after Tom Yawkey’s wife Jean—provides pizza, libations and, yes, ping pong, all under the name of Game On!

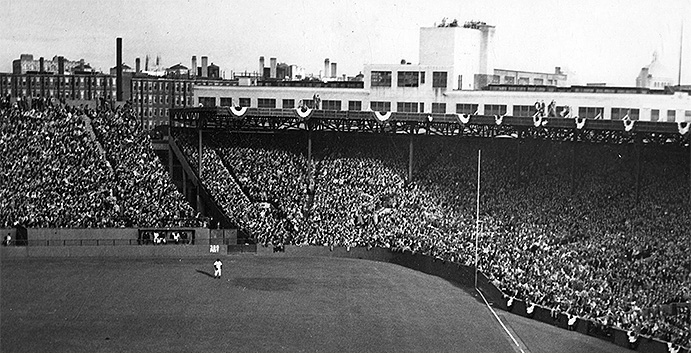

Fenway Park hosted four World Series during its first decade of existence, three of which involved the Red Sox. The neighboring Boston Braves were responsible for the fourth, abandoning ancient South End Grounds in the midst of their remarkable “miracle” run of 1914 and becoming co-tenants at Fenway, all the way through to their shocking four-game Series sweep of the high-powered Philadelphia A’s. Fenway’s 34,000 seats were better than South End’s sub-10,000, but 40,000 was even better; that would be the capacity of Braves Field, the Braves’ new home for 1915. Not only was Fenway suddenly too small for the Braves, it was for the Red Sox as well; when the Sox nabbed the AL pennant in 1915, they turned their backs on Fenway and borrowed Braves Field for the World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies, winning another world title while setting Fall Classic attendance records with crowds of over 41,000.

Fenway would prove that it could hold more than it sat when, in 1919, it drew perhaps its biggest gathering ever as upwards of 60,000 jammed the facility to listen to a speech from Irish revolutionary Eamon De Valera. Other non-baseball events permeated the Fenway schedule during its early years, including a rally with former U.S. president Teddy Roosevelt, a concert led by march king John Philip Sousa, and numerous college and high school football games.

Fenway Park’s sightlines are fantastic—unless you’re one of the unlucky fans sitting behind a post propping up the upper levels above. (Flickr—Kim Carpenter)

The Trouble With Harry.

The Red Sox had everything going their way during the 1910s. A new ballpark. Star power. Multiple championships.

Then Harry Frazee came along and messed it all up.

After the Red Sox won their second straight World Series title in 1916, Frazee bought the club and Fenway for roughly $500,000. He presided over the Red Sox’ fourth world title of the decade in 1918—and their last for the next 86 seasons—as he rode an awesome roster assembled by predecessor Joseph Lannin. But in Frazee’s world, baseball took a backseat to Broadway—and he used the former to finance the latter, sending most of his star talent for lesser players or money to recover from his stage flops. The benefactors were the New York Yankees, where most of the traded Red Sox ended up.

Frazee’s most egregious—and telling—trade during this period came after the 1919 season when he sent Babe Ruth, wunderkind pitcher and emerging Atlas, to the Yankees for a whopping $125,000. If that wasn’t enough, the Yankees loaned Frazee an additional $350,000 with Fenway Park as collateral. In other words, the Yankees essentially owned Fenway until Frazee paid them back.

By dealing Ruth, Frazee was giving up on one of the best pitchers Fenway has ever seen—and one of the greatest hitters it never got to fully embrace. Ruth’s 1.95 earned run average at Fenway, paired with a lifetime 49-19 record and 11 shutouts, is second to none at the ballpark. After donning pinstripes at New York, Ruth returned to Boston as the enemy and inflicted the expected massive damage with his bat, hitting .333 in 519 at-bats with 38 home runs and 119 RBIs as a Yankee at Fenway.

The ripple effect of Frazee’s disastrous ruin would reverberate around Fenway for 10 long, painful years after he sold the club in 1923. The Red Sox were usually eliminated from pennant contention on Opening Day, often losing over 100 games; they struggled in vain to turn a profit while every other team easily cashed in on the hitting frenzy of the 1920s; and attendance sank to an all-time Fenway low 182,000 in 1932, a year in which the Sox lost a record 111 games. Nothing was done to update Fenway Park—in fact, fire did all it could to ruin it when not one but three blazes broke out in the wooden bleachers down the left-field line over a two-day period in 1926, destroying the structure. Rather than rebuild, Frazee’s successor Bob Quinn swept away the ashes and left it vacant because he didn’t have the money—or the incentive, given that few fans would occupy the seats anyway during this depressed time in Red Sox history. The team’s state of being became so sad, someone with a socialist bent suggested that the Yankees give back some of the players gifted earlier to them by Frazee. Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert chuckled in response, “There is no charity in baseball.” Or crying, as the few hardcore Red Sox fans were by then doing.

Fenway Park’s wooden grandstand seats are the same ones installed during the 1934 makeover of the ballpark. (Flickr—Arturo Pardavila III)

Fenway 2.0.

In February 1933, just four days after inheriting $3.4 million from his late foster father, 30-year-old Thomas Austin Yawkey decided to spend a chunk of his newfound riches on the Red Sox, buying the franchise for $1.5 million. Red Sox fans were wary that Yawkey, like Frazee before him a New York City resident, would extend the tradition of generously giving to the Yankees down the street. On the contrary; he aggressively began to build the team back to prominence, purging a no-name, second-division roster in favor of one spiced with All-Star flavor as Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Wes Ferrell and Heinie Manush joined the fold. Yawkey’s lavish spending didn’t stop with the purchase of talent; he also wanted to update Fenway Park. Not with a fresh coat of paint, but with an overhaul.

Yawkey would spend almost as much money rebuilding Fenway as he did purchasing the ballclub, though it wasn’t budgeted that way; he had to reach deeper into his pocket on January 5, 1934 when a spectacular fire wreaked havoc from the third-base side to the center-field bleachers. Laborers eager to work around the clock in depression-era Boston helped speed up the re-rebuild and get the renovated Fenway completely ready for Opening Day three months later.

The new Fenway, with capacity upped to 37,500, would essentially be what Red Sox fans see today, minus all the modular updates tacked on over the years. In fact, the seats in the main grandstand are still in use, polished and refurbished to meet the discernable expectations of the modern fan. They are the only wooden seats currently being used at any major league ballpark.

What Yawkey’s makeover most memorably begat was the Green Monster, replacing the old wooden wall and Duffy’s Cliff in front of it. It wasn’t green at first, but instead the world’s biggest bulletin board as the 37-foot-tall, 231-foot-wide wall made of railroad ties covered by tin was completely overwhelmed with three giant ads and, at its base, a long, hand-operated scoreboard. Outfield barriers at other ballparks of the time rivaled the height of the Green Monster, but they’re all gone now. The Monster remains, and its current-day status as a sole survivor endears fans as they continue to watch it grant medium-fly home runs, knock back deep, scorching line shots and drive unschooled outfielders crazy as balls unpredictably rebound back onto the field. Babe Ruth—but of course—would grab the honor as the first player to clear the wall in a regular season game.

Home run souvenir hunters trolling behind the Monster loved the wall as much as Lansdowne Street business owners hated all the broken windows and dented storefronts they were forced to absorb, so in 1936 the Red Sox pandered to the latter by installing a 23-foot-tall net atop the wall to reduce future outside damage. To fetch all the balls that gathered at the base of the net, the Red Sox tacked a ladder to the wall—providing yet one more source of aspirin-inducing volatility for outfielders bracing for an any-which-way ricochet.

The greening of the Monster took place in 1947 when all the ads were removed. The muted, industrial green has become well represented beyond the Monster at Fenway, with all outfield walls and steelwork splashed in the color. The Red Sox claim they own the rights to the color, and in 2014 they made an arrangement with Benjamin Moore to sell “Green Monster” paint for homeowners to use on their backyard fence, garage door or man cave walls.

Fenway Park’s right-field corner during the 1946 World Series shows the wall curling to meet the foul line just 302 feet from home plate; it’s currently the shortest distance to a pole anywhere in the majors. (The Rucker Archive)

Just Another Ricochet Off the Wall.

Tom Yawkey’s rejuvenation of both the Red Sox and Fenway gave Boston fans a jolt of energy as the team became not only became competitive once again, but fun to boot. They weren’t ready to overtake the mighty Yankees—yet—but they emerged as such a threat that the Yankees, who never got back the $350,000 they had loaned Harry Frazee, wanted it back pronto. On the field, offense became the name of the game at Fenway, as the Red Sox matured into a consistent force at the top of the batting charts; during his 1938 AL Most Valuable Player campaign, Jimmie Foxx hit .405 with 35 home runs and 104 RBIs just at Fenway alone. He’d be joined a year later by an even more dominant hitting presence in Ted Williams, the tall, lanky and brash left-handed slugger whose keen hitting insight and outspoken disposition ignited a love-hate relationship with both Red Sox fans and reporters over the next two decades.

After Williams’ stunning rookie debut (.327 average, 31 homers, 145 RBIs, 107 walks) in 1939, the Red Sox decided to rig Fenway to potentially sweeten his numbers even more. They took the bullpens, previously squeezed in down the lines, and plunked them in a space behind a moved-in right-field wall that shortened the field dimensions from right-center to the right-field foul pole by some 20 feet. The relocated bullpens, along with the added seats filling in the rest of the former outfield space, gave rise to the name “Williamsburg”; meanwhile, the right-field foul pole, now resting just 302 feet away from home, eventually acquired its own nickname of the “Pesky Pole” in honor of popular light-hitting Red Sox second baseman Johnny Pesky, who hit just six homers—all of them, it seemed, near or off the pole—in 539 career games at Fenway.

Outfielders in center and right once felt they had it easy and laughed at the angst piled up by teammates attempting to tame the Monster in left. But now the reconfigured right side of the outfield presented increased challenges of its own.

The relocated bullpen sliced into the deepest part of the center-field wall at a 90-degree angle—an area now simply referred to as “The Triangle”—and increased the number of tricky caroms for center fielders to predict. Right fielders, meanwhile, have had to constantly remind themselves how close the bullpen now wall is; Detroit’s Torii Hunter found this out in the worst way during the 2013 American League Championship Series when, while racing back to catch up to a David Ortiz deep fly, he hit the short wall hard and flipped completely over into the bullpen, legs up as he came down head first. (He didn’t catch the ball.)

Ironically, the shortened right-field area didn’t initially aid Ted Williams’ power base—he hit only nine homers at home in 1940 after Williamsburg became established—but it far from neutered his overall game, as he twice hit over .400 at Fenway during his career—including a .428 mark during his fabled 1941 campaign in which he produced the last overall .400 average by a major leaguer to date.

Detroit’s Torii Hunter takes his famous fall into the bullpen behind Fenway’s low right-field wall during the 2013 playoffs. He was hardly the first to accidentally find himself in the pen. (Associated Press)

Opponents tried unorthodox methods to shut down the Splendid Splinter, most memorably by stacking the right side with fielders in one of baseball’s first variations of the “shift,” but they couldn’t station themselves behind the outfield wall, where Williams would frequently deposit his deep flies—very deep, at times. In 1946, well rested after serving three years in the military during World War II, Williams launched what’s generally considered Fenway’s longest ever home run, a 502-foot drive that landed high up in the voluminous right-field bleachers and glancing off the straw hat of an unsuspecting fan. “They say it bounced a dozen rows higher,” the victim told the Boston Globe, “but after it hit my head, I was no longer interested.”

Over six decades later, a reporter took David Ortiz aside and pointed out the seat—painted red in 1984—where Williams’ tape-measure shot landed. The muscular Ortiz, who had the capacity to match Williams foot for foot with a home run blast, squinted his eyes as he labored hard to find the speck of red high up in the bleachers. He turned back to the reporter. “Bulls**t,” he said.

The runs racked up at Fenway during Williams’ reign, as the shortened dimensions in right—combined with the looming Monster just 315 feet down the left-field line (re-measured at 310 in 1995)—turned the ballpark into a hitter’s dream world. The Red Sox were perennial AL leaders in both batting average and runs tallied, and it all peaked in 1950 when they became the last team to date to hit over .300—they hit a remarkable .335 at Fenway—and notched 1,027 runs, 625 of those at home for an average of over eight a game. Only the 1999 Cleveland Indians have since surpassed 1,000 in a season, though they needed eight more games to do it.

Boston’s bludgeoning offense hit a powerful crescendo in the midst of a midweek 1950 series against the lowly St. Louis Browns, romping by back-to-back scores of 20-4 and 29-4. Three years later, the Red Sox piled up anew when they plated an all-time record 17 runs in one inning against the Detroit Tigers—an achievement all the more impressive considering that Ted Williams, back in the service flying warplanes in Korea, wasn’t even in the lineup.

Thirty-seven rows behind the right-field fence, a red seat denotes the spot where Ted Williams’ 502-foot home run—the longest ever hit at Fenway Park—landed during a 1946 game. (iStock)

Tom Yawkey did not rest on Fenway during the postwar years. Lights were installed in 1947, skyboxes were first introduced in 1949, and the media were more than accommodated not only with an expanded press box atop the grandstand roof and a separate TV booth below, but with a lavish lounge built for reporters behind the press box where they could pick from a buffet, drink from a bar and have space to write their stories in air-conditioned comfort. Down below the stands, the Red Sox thought it wise to construct a separate clubhouse tunnel for visitors after a fight broke out between the Sox’ Jimmy Piersall and the Yankees’ Billy Martin—two bellicose personalities you wouldn’t want to see crossing paths in a bar, let alone a shared tunnel to the field where the fracas took place.

All in all, these were good times for the Red Sox and Fenway, with attendance springing well over a million for much of the first 10 years after the war. But Fenway, Yawkey and Williams could not channel all the enthusiasm and mold it into a championship trophy. The Red Sox managed one AL pennant in 1946—their lone flag over a 49-year period—but conceded the ensuing World Series in the full seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals, and lost out on back-to-back opportunities for pennants in 1948-49 when they tantalizingly finished a game shy of first place.

The Shaming of Fenway.

When 42-year-old Ted Williams stroked his 521st home run in his final career at-bat in 1960, it truly signaled the end of an era at Fenway—and nearly the beginning of the end for Fenway itself. Baseball fans—and America and general—began turning their backs on decaying inner cities and the aging steel-and-concrete ballparks like Fenway that inhabited them, yearning instead for the promise of Progress City. Compounding the problem for the Red Sox was that Williams’ departure left a significant void of character and talent, a young Carl Yastrzemski excepted. The team suffered through eight straight losing seasons, including a miserable 100 losses in 1965. A game at the end of 1964 drew a mere 306 fans to Fenway. Of course, everyone took their anger out on the aging ballpark. Sports Illustrated called the 50-year-old yard “ancient, obsolete.” Tom Yawkey agreed, telling The Sporting News that he was “willing and anxious” to move out of Fenway to a new facility with “adequate parking and fair rental.”

Fenway Park had previously survived many attempts to have it replaced. The death watch dated as far back as the late 1920s, when Blue laws prohibiting Sunday baseball in Boston briefly prompted the Red Sox to look at building a new venue north of Boston in the neighboring city of Revere. But starting in the late 1950s, the ballpark came under assault from a daily barrage of news stories and civic efforts to build something new for the Red Sox and other local sports teams. One private group, headed by former Red Sox center fielder Dom DiMaggio—an investor in football’s fledgling Boston Patriots, which briefly called Fenway their home—proposed a domed, multi-purpose stadium in the southwestern suburb of Dedham. One of those multiple purposes would include dog racing, which was vehemently opposed by a powerful dog racing lobby that feared competition. Dedham eventually hit a dead end.

The state of Massachusetts—or more accurately, the state’s turnpike authority—picked up on the domed stadium concept and suggested a new landing spot 10 miles west of Boston in Weston. Why would turnpike authorities be so interested in a sports facility? Because it would be located right off the Massachusetts Turnpike, naturally. The plan ultimately died under the weight of a proposed $55 million price tag, giving Fenway another reprieve.

What most likely put an end to the search for a Fenway replacement—and initiated a new lease on life for the ballpark—was the 1967 Red Sox, who made a completely unexpected turn for the best behind Yastrzemski’s triple-crown performance and Jim Lonborg’s 22 victories to win an excruciatingly close pennant race. Though the “Impossible Dream” run failed to end the Sox’ long championship drought—again falling in seven games to, again, the Cardinals—it re-awoke a slumbering, recently disinterested Red Sox fan base that poured through Fenway’s turnstiles a record 1.7 million times, establishing a new normal that would gradually only rise in the years to come.

A look up close and personal at Fenway’s left-field foul pole—officially named the Fisk Pole in honor of Carlton Fisk, who struck it to win Game Six of the 1975 World Series—reveals a din of graffiti. (Flickr—Eric Kirby)

We Still Love You.

As the Red Sox embarked on a lengthy tide of success—posting winning records over 16 straight years through 1983—there was a re-embracing of Fenway Park, especially as many of the steel-and-concrete gems of its era fell, one by one, to the wrecking ball. It thus became more precious and special, a relic with an emerging value that fans and team brass alike could not quantify in dollars. “If it were up to me,” wrote the San Francisco Chronicle’s Art Spander, “they could tear up all the new, steel-and-cement, multi-purpose stadia…and replace them with antiquated ballparks in the middle of the urban blight, ballparks like Fenway.” And after Tom Yawkey spent much of the 1960s telling anyone willing to listen that he wanted out of Fenway, the front office reversed its position as one Red Sox executive, asked about the team’s progress on searching for a new facility, responded, “What do we need (a new stadium) for?”

Fenway Park truly completed its 180-degree journey from jewel to junk to national treasure in 1975, the year the Red Sox returned to the World Series behind the double-barreled rookie might of outfielders Fred Lynn and Jim Rice. The ballpark was prominently featured in the sixth and seventh games of that year’s classic World Series against Cincinnati, especially in Game Six when Boston catcher Carlton Fisk willed a 12th-inning deep fly down the left-field line to stay fair, frantically waving his arms first fair-ward. The ball cleared the Green Monster and hit the foul pole, winning the game for the Red Sox and setting up a seventh game that, all too predictably, ended in defeat once more for championship-starved Boston.

Few changes were made to the ballpark during its resuscitation years. The most intriguing modification came in 1976 when, after watching a fearless Fred Lynn repeatedly run himself into the outfield wall in pursuit of deep flies, the lower portion of the Green Monster and adjacent center-field wall was finally padded. The long scoreboard at the base of the Monster was also shortened in length, eliminating out-of-town scores from National League games (it would be widened back in 2003), and the Monster itself was remade with a plastic covering to replace the tin—which was removed, cut into small pieces and sold as souvenirs to benefit the locally-based Jimmy Fund to help fund cancer care and research.

One of Fenway’s oddest trademarks arrived on the scene during this period: The Citgo sign. At first glance, there’s nothing terribly nostalgic about the sign—it’s a giant, illuminated billboard displaying a modern logo for a Venezuelan petroleum company—and it’s located nearly 1,000 feet away from Fenway, perched atop a six-story building across the turnpike. But the huge sign is easily visible to many within Fenway, and its distant location behind the Green Monster always ensures that it will get TV time when a deep fly is hit towards the tall wall. First hoisted up in 1965, the Citgo sign has become beloved by Fenway fans who consider it to be so much of the ballpark’s aesthetic, they’ve taken on the role of preservationists to keep it there. As of this writing, the City of Boston is considering giving the sign landmark status.

Tom Yawkey died in 1976, leaving control of the franchise in the hands of his wife Jean and two new investors. The track record of widows being bequeathed with major league ownership had not always been good, so Red Sox fans understandably braced for something of a lame duck period under the partial rule of Ms. Yawkey. But in a reign that lasted until her passing in 1992, she presided over a ballpark that hardly sat inert of updates. A second deck of sorts was finally added with the addition of modern luxury boxes and additional seating down the lines; a scoreboard behind the center-field bleachers was updated with a video board—one that sent a secret message to Kevin Costner in Field of Dreams; and in 1989, the area behind home plate took on a whole new look with a voluminous structure above the field level. The lower half was home to an exclusive seating area currently called the Dell EMC Club, where ticket holders have access to high dining via a restaurant in the back; above, the press box was bumped upward by the new club section, and was made more expansive and comfortable—but it was small comfort for media members who complained that they were now too high up above the action.

A look from the outside toward Fenway Park’s left-field foul pole reveals a complex menagerie of stairways and egresses that stresses reason over rhyme. (Flickr—DJAnimal)

Fenway to Heaven?

Just when it appeared that Fenway Park looked safe for the long haul, its impending ruin was placed back on the agenda in 1999. This time, it had nothing to do with a crumbling ballpark in a crumbling urban wasteland. Instead, it had more to do with the realities of modern-day revenue streams—realities that John Harrington, who took over ownership of the Red Sox after Jean Yawkey’s death, no longer thought could be realized at Fenway.

Maxed out on capacity and amenities, Harrington lobbied the City of Boston to forcibly take over land to the immediate west of Fenway and build a new Fenway, one that would retain the same field dimensions and the Green Monster but would also be constructed on more expansive space to allow for 44,000 seats (11,000 over the current Fenway), wider concourses and over 100 luxury boxes. The Red Sox were willing to privately finance the building of the new ballpark but leaned on the city for $300 million in external infrastructural upgrades, mostly related to transportation. The city agreed, but the neighbors did not; they threw up enough resistance that both team and city backed off. Within two years, Harrington gave up not only on the new Fenway but the Red Sox in general, selling the franchise.

The three-man ownership group that succeeded Harrington once again left Red Sox Nation skeptical. It included John Henry, who couldn’t make a go of it in Miami with the Florida Marlins, and Tom Werner, whose first dalliance with major league ownership in San Diego was best remembered for engineering a budget-hacking fire sale, a lawsuit from season ticket holders and his ill-fated decision to have Roseanne Barr sing the National Anthem before a Padres game. But then there was the third guy seated at the Red Sox’ new Roundtable: Larry Lucchino, whose front office rule with the Baltimore Orioles included his presiding over the building of Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which ushered in the retro ballpark age. Lucchino, along with the other two co-Lords, agreed that the Red Sox should not only stay at Fenway, but improve upon it; his bright idea was to bring in Janet Marie Smith, the energetic urban planner who crucially gave Oriole Park its kitsch and genuine vibe, to help perform such a rehab on Fenway.

Sweet.

No time was wasted on enhancing the Fenway experience. The Red Sox got permission from the city to shut down Yawkey Way between Brookline and Van Ness to auto traffic on game days, essentially providing an external concourse, a la Eutaw Street behind Oriole Park’s right-field bleachers. Meanwhile, the concourse behind Fenway’s right-field seats was doubled in width to 60 feet and appropriately called The Big Concourse. Roomy dining and picnic areas were developed on the expanded second deck, including the Budweiser Deck in the right-field corner—using oak wood from the extinct bowling lanes in the Jeano Building to form the main bar.

The most noticeable change from the new regime came with the creation of the Green Monster seats, three rows of barstool-like seats and counters atop the wall. They’re arguably the most popular bleacher seats in the majors—and certainly the most expensive, with prices often topping $500 per seat; if you want to save a little money, you might be able to get standing room access atop the Monster for as little as $50.

Red Sox fans ate up the updates and descended upon Fenway Park as never before, pushing seasonal attendance over the three million mark. On May 15, 2003, a 12-3 Boston victory over the Texas Rangers was witnessed by a sellout crowd of 33,801; over the next 10 years to follow, there would not be a single unsold seat at Fenway. The streak of 827 straight sellouts shattered the majors’ old mark of 455 (previously held by Cleveland) and set an all-time North American pro sports record.

Other traditions began. One night in 2002, the Red Sox’ in-game entertainment folks decided to play Neil Diamond’s 1969 ballad Sweet Caroline in the middle of the eighth inning—and it stuck. It has become an anthem for the eighth-inning stretch; Diamond himself once showed up to serenade the crowd.

The Green Monster today, with its recently added three rows of seats above, expanded scoreboard and subtly displayed ads to blend in with the industrial green aesthetic. (Flickr—Justina Newton)

By the end of the 2000s, there was good reason for Boston baseball fans to be in a singing mood. The Red Sox, denied again and again and again in what seemed an endless quest to win it all for the first since 1918—they had since lost four World Series, all in seven games, all under heartbreaking circumstances—finally broke through in 2004. Achieving their first world title in 86 years was like a page torn right out of ‘Ripley’s Believe It or Not’: One inning away from being swept in the ALCS by the archrival Yankees at Fenway Park, the Red Sox pulled off a come-from-behind victory over closer supreme Mariano Rivera, won the next three games to stagger the Yankees—then blew past the Cardinals in four straight to claim the trophy. Three years later, they performed another series sweep of a frisky Colorado Rockies side, and won it all yet again in 2013, capping an utterly emotional year in which the Red Sox healed an emotionally fractured city broken apart by the Boston Marathon terrorist bombings earlier in the year.

Today, Fenway Park is alive as ever. The industrial malaise surrounding the ballpark 50 years earlier has long since given way to a healthy dose of gentrification, as one luxury hi-rise after another is popping up to the immediate south and west of the yard. Fans take advantage of the pre- and post-game scene outside of the ballpark, especially on Lansdowne Street where the action is especially ripe with numerous chic dives such as the House of Blues, the Cask’n Flagon and the Bleacher Bar, set up by the Red Sox themselves under the center-field bleachers.

Inside, the Red Sox have overcome the argument that they’ve hit the ceiling on revenue potential at Fenway. They keep finding ways to sweeten the coffers, all without bastardizing the aesthetic. Game tickets, parking and food have never been more expensive, but as long as the team keeps winning, the joint keeps selling out and the park stays on everyone’s bucket list, few will complain. Ads have returned on the Green Monster, but they’re subtle and drawn out in white—apparent but transparent to maintain the dignity of the green wall. And baseball ain’t all that’s happening at the ballpark; it’s taken on more of a multi-purposed life, with room for college football, soccer exhibitions, political rallies and even the occasional outdoor hockey game. Concerts returned in 2003, 30 years after the last one, a jazz festival, was plagued by violent chaos; among the more recent headliners are the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Dave Matthews Band, Bruce Springsteen, Roger Waters (performing—yes—The Wall) and, of course, Neil Diamond.

Finally, for more than a few bucks, you can get married at Fenway Park—though one wedding party scattered in horror during a ceremony in 2009 as numerous gunshots suddenly echoed throughout the park. Turns out, they were fake rounds of ammo emanating from the set of The Town, a tale directed by and starring avid Red Sox fan Ben Affleck about a heist at Fenway. The film featured a memorable line when one criminal, laughing his way out of Fenway with a stash of the loot, proclaimed, “No one’s robbed the Sox like that since Jack Clark!”

Some people just can’t get enough of Fenway Park. Even the Red Sox can’t. In 2012, they opened Jet Blue Park, their new Florida spring training home at Fort Myers with field dimensions and fence heights to match exactly those of Fenway, including the Green Monster—though there’s an open slat in the middle of the wall for fans to watch through, as hurricane-safety regulations do not allow for a continuous wall so tall. Jet Blue Park isn’t even the only Fenway clone in Florida; in 1989, Bucky Dent—the light-hitting ex-Yankee who broke Red Sox hearts the world over with his implausible home run over the Monster to cap Boston’s 1978 pennant race collapse—built a baseball facility in Delray Beach that included a full-scale copy of the Green Monster and scoreboard frozen at the moment when Dent stepped to the plate during that infamous Red Sox-Yankee playoff. To help christen in the facility, Dent invited Mike Torrez, the Red Sox pitcher who served up his home run, to pitch to him—for old time’s sake. Torrez accepted, threw—and on cue, Dent lofted another somewhat deep fly over the replicated Monster.

The question remains: How long can Fenway Park last? A recent engineering study says the park can hold up through 2061, if the Red Sox want to stay that long. At this point, the mere thought of the Red Sox playing anywhere else in fraught with blasphemy. Yes, getting there is a pain. The seats are not wide enough. The posts get in the way. The beers are too damned pricey. The bathroom lines are too long. And so on. But once you sit within what author John Updike called a “lyric little bandbox of a ballpark,” focus on the field and behold the blissful disproportions of the field, the wall heights and the levels of insanity endured by the players, you all too quickly realize just how worth it the experience is.

Boston Red Sox Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Red Sox, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.