The Ballparks

Municipal Stadium

KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI

(OTBP)

It was a pit stop for the many who played there, but never a pit—an artless but fully pragmatic ballyard with the visual flourishes provided by its many colorful performers. From Muehlebach to the Monarchs to the Mule, Municipal Stadium was the constant over 50 years of Kansas City’s ever-changing baseball landscape.

When emerging baseball fans browse through the list of long-gone major league ballparks, they quickly latch onto the names of iconic venues, hallowed grounds like Ebbets Field, Shibe Park and the original Yankee Stadium. Conversely, Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium doesn’t attract the eyeballs, like the homely girl passed up at the high school dance or the Camry sitting among the Porsches and Jaguars at the car lot.

Such indifference would be understandable. First of all, there’s the name. Municipal Stadium. It sounds like something that radiates with all the excitement of a generic store-brand box of corn flakes. Then there’s the architecture. There was no palatial home plate entry or exquisite adornments; most people entered through a concrete block structure near the right field corner that could have easily been confused for a modest little warehouse. Finally, there’s the history. Too many people perceive of Municipal Stadium only as a place that hosted major league baseball for barely two decades with terrible tenants who rarely ever won.

But beyond its dull exterior and insubstantial reputation, Municipal Stadium is full of rich, exciting and colorful tales, home to many legendary baseball names who briefly shined or captivated nationwide attention (good or bad) before making for bigger and better fame elsewhere. From the minor-league Blues and Negro League Monarchs to the maddening Athletics and infant Royals—not to mention a shot of football excellence toward the end of its 50-year lifespan—there was seldom a dull moment at the Muni.

Junior Class.

Kansas City experienced, but could not sustain, major league representation before Municipal Stadium was built. Losing had something to do with it; the combined record for the three versions of the Cowboys—in the Union Association (1884), National League (1886) and American Association (1888-89)—and the Packers of the short-lived Federal League (1914-15) was a miserable 292-481. Ballparks used for these teams were predictably rickety and short-term, and didn’t lack for rowdyism in a time when the Wyatt Earp mindset held stubborn at the gates to the territorial West; it’s said that one venue posted a sign that read, “Please do not shoot the umpire. He’s doing the best he can.”

By the turn of the century, healthy population growth had turned Kansas City into a gentler, more widespread urban community. Among the city’s more prominent names at this time was George Muehlebach Jr., whose father had migrated from Switzerland in 1859 and started a brewery that would emerge as one of the region’s largest by time he died in 1905. Junior took over at the soft age of 24 and felt the need to diversify—a wise move given the coming onset of Prohibition. In 1916, he built the Hotel Muehlebach—a palatial 500-room inn that would be Kansas City’s go-to for political and pop cultural royalty during much of the 20th Century—and nosed into banking and healthcare, mostly at the board level.

Muehlebach also loved baseball. He played on the brewery team and, in 1917, bought the Kansas City Blues, a charter member of the minor-league version of the American Association, established in 1902. The purchase didn’t include the ballpark, Association Park, built on land owned by the railroads; when Muehlebach learned that plans were in the works to run tracks through the facility, he decided it was time to build something new for the Blues.

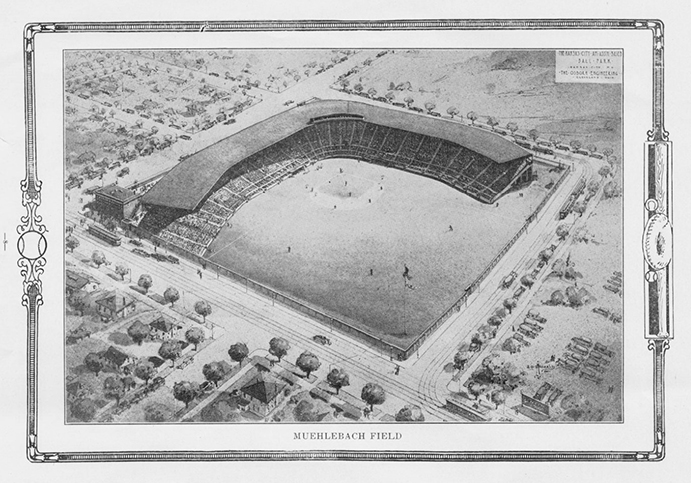

Just a few blocks from Association Park, Muehlebach Field—the first of four different names given to Municipal Stadium—was planted in a quasi-rural area some two miles southeast of downtown Kansas City. The previous history of the site is fuzzy; some say it was a swimming hole, others claim it was a frog pond, and a few more recall it as a giant ash pile. Seating 17,000, Muehlebach Field consisted of a single covered grandstand that stretched from the right-field wall to halfway between third base and the left-field wall. It was an architecturally spartan structure, with little if any ornamentation to boast.

Muehlebach Field’s playing field was initially immense. Permanent outfield walls were constructed practically to the edge of the property in left field to Olive Street (363 feet down the line) and in right to 22nd Street (390 feet), with the two connecting at the deepest part of the yard in straightaway center, a staggering 559 feet from home plate. At that corner, the field was level with the street elevation—but 22nd Street rose 40 feet uphill toward the right-field corner, leading to an imposing embankment, in play, called Brooklyn Bank. Houses dotted the other side of 22nd, granting residents virtual unobstructed views to watch games for free from their second-story windows.

Both the Blues and Muehlebach Field were a smash hit during the venue’s inaugural 1923 season. With a roster of former and future major leaguers—and some who never made the cut, like colorfully-named slugger Bunny Brief, who managed 29 home runs with the new yard’s expansive outfield—the Blues finished 112-54, won the AA title, and drew a then-minor league record 430,000 spectators. The Blues would set more attendance records in the years to follow; in 1927, they set a single-game AA mark with 30,000 and, 13 years later, broke the record for a minor league All-Star game when 18,499 showed up to watch the Blues take on a team made up of the AA’s best of the rest.

An artist’s rendering of Muehlebach Field—as Municipal Stadium was original named—from an introductory program for the first game featuring the ballpark’s first tenant, the minor-league Kansas City Blues. (Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library)

The Fabulous Monarchs.

From a historical perspective, the Blues were not the most famous tenant at Muehlebach Field before the arrival of the A’s from Philadelphia in 1955. The Kansas City Monarchs began play in 1920 as a charter member of the Negro National League, and dazzled with an array of African-American talent that easily had the chops to compete with the best of major leaguers—as some would get the chance to prove in later years. Among those wearing the Monarchs uniforms were Satchel Paige, Turkey Stearnes, Cool Papa Bell, Elston Howard, Ernie Banks, and Willard Brown—one of the very few players, white or black, to power a ball over Brooklyn Bank and the distant right-field wall behind it. The Monarchs also provided a professional launching pad for Jackie Robinson, who in 1945 played his one and only year in the Negro Leagues before the Brooklyn Dodgers snatched him away, batting .375 with four home runs and 27 RBIs over 26 games.

The Monarchs were founded by J.L. Wilkinson, the NNL’s only white owner who never saw diversity as a barrier to fielding a team; before putting together the Monarchs, he had run an all-female squad (allowing men wearing wigs to occasionally infiltrate) and later a diverse barnstorming outfit labeled the All Nations team that consisted of white, black and Native American players as well as those from Japan, Cuba, France, Germany and the Philippines.

Wilkinson’s quiet, humble demeanor was a complete antithesis to his teams’ colorful characters, but he was hardly afraid to innovate. In 1930, he mortgaged his house to purchase portable lights to surround Muehlebach Field, making the Monarchs the first professional baseball team to introduce night ball. When the Monarchs went on the road—as they mostly did as a barnstorming unit during the mid-1930s at the height of the depression—they brought the lamps with them, setting up and showing off under the lights and stars before thousands of curious fans around the country.

One of the first night games at Muehlebach Field, on August 2, 1930, provided the setting for arguably the greatest pitching duel in Negro League history. Chet Brewer started for the Monarchs; opposing him was Joe Williams, a plucky 44 years of age for the Homestead Grays. The game went scoreless into extras and was finally decided in the 12th when the Grays’ Cheney White doubled home Oscar Charleston for a 1-0 win. Both pitchers went the distance, with Brewer taking the loss despite giving up four hits and striking out 19. But that was nothing compared to the performance of Williams, who conceded just one hit and collected an astonishing 27 K’s. The lighting system, which pales greatly to what people are used to today, may have had an impact on the hitters’ inability to make contact—but so may have the ball, as Negro Leaguers were still allowed to cut, shine and spit on it 10 years after the majors outlawed such practices.

The Monarchs were far from a secondary source of baseball entertainment for Kansas City fans; while they may have been routinely outdrawn by the Blues, they were given just as much fanfare, with lavish Opening Day downtown parades and occasional exhibitions against teams made up of star major leaguers. And they hardly ever lost; during their time at Muehlebach/Municipal, the Monarchs nabbed 10 pennants and won two Negro League World Series, rarely ever finishing below the .500 mark.

Pinstriped Blues.

Needless to say, the seating at Muehlebach Field was never segregated for the Monarchs. The Blues, however, were a different story—at least until 1933 when George Muehlebach Jr., financially beaten up by both the depression and prohibition, sold the team to Kansas City native Johnny Kling, a former major league catcher who started for the Chicago Cubs’ championship squads of 1907-08. Kling tapped into and encouraged the largely African-American fan base of the Monarchs, who at this time were mostly barnstorming outside of Kansas City; with integration in effect, the Blues slowly came back to life both at the gate and in the standings. And then, just four years after he bought the Blues, Kling sold. The new buyers were none other than the holy New York Yankees, who turned the Blues into one of their top minor league affiliates and tantalized the town with the opportunity to showcase the Ruths, Gehrigs and DiMaggios of tomorrow, today.

Under Yankee control, the new Blues updated Muehlebach Field. The joint was repainted, new fences were inserted inside the original street-side walls to reduce the park’s voluminous outfield, and an improved lighting system replaced an inferior set of lamps put up five years earlier. The ballpark was renamed Ruppert Stadium after Yankees’ owner Jacob Ruppert, then again to Blues Stadium in 1946, seven years after Ruppert’s death. Finally—and alas—segregation in the stands returned. Not only were the Yankee-fied Blues biased against African-Americans, but little people; in a local 1938 advertisement promoting tryouts for the team, they advised that anyone shorter than 5’7” and weighing less than 150 pounds need not apply.

In the Blues’ 18 years as a prime Yankees affiliate, a who’s who of future pinstriped greats passed through Ruppert/Blues Stadium. Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Phil Rizzuto, Elston Howard and Billy Martin were among those who primed themselves at Kansas City, as did others (Al Rosen, Lew Burdette and Vic Power) who eventually starred after being dealt to other organizations. Vince DiMaggio, who never played for the Yankees but featured one year for the Blues in 1939, made the most of his brief stay by clouting 46 home runs to match a family record (Joe DiMaggio also hit 46 for the 1937 Yankees). Kansas City native Casey Stengel piloted the 1945 Blues, four years before beginning a highly successful 12-year run (10 pennants, seven World Series rings) as Yankees manager. Even the Blues’ front office provided a breeding ground for top future executives such as Frank Lane and Lee MacPhail.

As a Yankees farm club, the Blues were party to some of the ballpark’s more memorable games. On June 26, 1947, pitcher Carl DeRose—a faded pitching prospect barely hanging on with the Blues, was facing imminent surgery but asked for one more start. He got it, and he delivered—throwing the first perfect game in American Association history, blanking the Minneapolis Millers on 93 pitches as he fought off tears throwing in excruciating pain. Then there was the curious case of Al Cicotte, nephew of Chicago Black Sox pitcher Eddie Cicotte, who on May 7, 1953 threw a one-hit shutout for the Blues. He was rewarded with a demotion following the game. Why? Because he walked 13 batters.

Finally, there was a moment few people know about; on June 12, 1939, six weeks after playing in his 2,130th straight and last major league game, Lou Gehrig took the field one last time for the Yankees, visiting Kansas City to take on the Blues in an exhibition. Before an overflow crowd of 23,864 at Ruppert Stadium, Gehrig—who initially declined to play but changed his mind because he felt he owed it to the fans—played three innings, grounded out in his only at-bat and completed four errorless chances at first base. After the game, Gehrig traveled straight to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where doctors told him that he was dying of ALS.

A sellout crowd welcomes the A’s for their first-ever game at Municipal Stadium in 1955. A second deck was added to the facility, doubling the ballpark’s capacity to over 30,000. (Flickr—Missouri State Archives)

From Murmurs to Majors.

Like most minor league teams, the Blues were crushed by the paucity of baseball talent and general domestic restrictions during World War II; by 1944, they drew a scant 37,199 for the entire season. But after the war, visions of boom times seduced Kansas City into passing a $1.25 million bond to improve Blues Stadium should the need ever arise, ideally to lure a major league team to the area. Though the majors had been entrenched for nearly 50 years without a single franchise relocation, America’s westward postwar expansion presented at least the prospect of such an opportunity.

That scenario became substantive starting in 1953 with the Boston Braves’ move to Milwaukee. The downtrodden St. Louis Browns, located 250 miles east of Kansas City, had also wanted to resettle to Wisconsin, and their failure to beat the Braves to the punch lit up the powerful typewriter of Kansas City Star sports editor Ernest Mehl, who began writing up story after story of how Kansas City could be the Browns’ next, permanent stop. The articles picked up big-time legs, and the city became abuzz in baseball relocation fever.

In August 1954, another bond to fix up and double Blues Stadium’s size to 34,000 passed with an impressive 83% voter approval. The Browns had already moved on to Baltimore, but Kansas City’s momentum to nab a big-league franchise hardly waned—especially after the late 1953 purchase of Blues Stadium by Arnold Johnson, a Chicago vending machine magnate who bought the ballpark from the Yankees as part of a much bigger deal to also buy New York’s Yankee Stadium. The locals correctly sensed that Johnson was interested in more than just ballpark ownership; he was seeking out a major league owner looking to make a move.

It didn’t take long for him to find one.

“We’re washed up in Philadelphia,” Connie Mack told the Boston Globe in August 1954. “I want to sell…There is no more interest in the team.” The long-time owner/manager of the Philadelphia A’s had seen his team roller-coaster through numerous cycles of boom and bust, but the neighboring Phillies had become stable and respectable enough to make the A’s a long-term second banana and convince the 91-year-old Mack that it was time to get out. There were some financial players—including one of Mack’s sons—vying to buy the A’s and keep them in Philadelphia, but major league owners were rightfully concerned about the city’s viability to sustain two teams.

When Arnold Johnson called, Mack listened. He offered enough to convince Mack to give him the franchise, then offered more when the Philadelphia buyers bulked up their bid. In the end, Mack literally snuck Johnson through the back door of his home and finalized the deal while the Philly group, thinking they had first dibs, fatally waited in the formal entry.

Kansas City finally had its big-league team—but before owners could approve, Johnson needed the city’s assurance that he was doing the right thing. He got it, one week and a million ticket requests later.

But now came the hard part: Reinventing Municipal Stadium—as it was finally now called after the city bought it from Johnson for $650,000—in just five months before Opening Day 1955. Compounding the stress of this tight timeline, engineers discovered upon closer inspection that the envisioned second deck—placed on top of the grandstand to double the ballpark’s capacity—wouldn’t work with the existing support pilings, leading to a complete teardown of the existing structure. This not only strained the schedule but the $2.75 million budget, resulting in the elimination of a planned extension of the first-level seats to the left-field foul pole, and more lofty elements such as a pedestrian bridge, the purchase of surrounding land for parking, a “stadium club” for season ticket holders and a “trophy room” showing off artifacts from the glory days of the A’s tenure in Philadelphia.

Harsh winter conditions didn’t help with the rebuilding process as delays threatened to make Municipal Stadium a partial facility on Opening Day; in the rush to get everything completed on time, the A’s forgot to install section numbers until the last minute. And rather than construct a whole new scoreboard, Arnold Johnson reached out to Milwaukee Braves owner Lou Perini—who still owned the all-but abandoned Braves Field back in Boston—and paid $100,000 for the old facility’s modern board.

Somewhat miraculously, Municipal Stadium was remade just in time for the Kansas City A’s debut on April 12, before a crowd of 32,844—the largest ever for any local sporting event up to that moment. Former President Harry S. Truman threw out the ceremonial first pitch while Connie Mack—alive, well and rich at 92—showed up and took a formal pregame bow to the fans. (George Muehlebach Jr., who oversaw the raising of the original structure, never saw the expanded product; he died three months earlier.) Though the A’s responded to the pageantry with a 6-2 win over the Detroit Tigers, there was no illusion that the Kansas City version of the A’s would be any less awful than the one that stank up the ballpark back at Philadelphia. They would lose their next four games by a combined score of 41-6, and during their second homestand on April 23, got walloped by the Chicago White Sox, 29-6—setting an American League record for runs that would last until the Texas Rangers notched 30 at Baltimore in 2007.

But the fans, in honeymoon mode, didn’t mind. When the A’s arrived back in Kansas City after the season’s first, short road trip in which they lost all three games, 5,000 fans greeted them at the airport. It took the A’s just 14 home dates to surpass their total 1954 gate at Philadelphia, and despite placing sixth in the AL with a 63-91 record, they drew 1.393 million fans at Municipal Stadium to finish second in league attendance behind the Yankees (1.49 million).

There were some tweaks made to Municipal Stadium after the first season, most pivotally in left field where the wall height was raised to 20 feet after a majority of the 180 home runs hit there in 1955, pushed along by prevailing south winds, missed breaking a then-AL season ballpark record for most dingers by just two. The team also brought in a young greenskeeper named George Toma, who did wonders turning an awful Municipal Stadium field into one of baseball’s best. Toma would become so esteemed at his craft, he eventually was tagged as the “God of Sod” and be called upon to prep the playing fields for the Super Bowl, Olympics and soccer’s World Cup.

While these improvements enhanced the integrity of Municipal Stadium, the product on the field continued to suffer. Arnold Johnson admitted he had inherited a talent-starved organization and was embarking on a five-year plan to strengthen the A’s into contender mode. But those five years yielded more of the same; losing records, deep placement in the AL standings, sinking attendance and rising chatter that the team, like the Blues before them, was nothing more than a farm club for the Yankees as the A’s “gave away” future New York stars Roger Maris and Ralph Terry, among others. Johnson fittingly capped the five years by unexpectedly dropping dead at age 54.

Combative A’s owner Charles Finley, upset that New York’s Yankee Stadium had a short 296-foot distance from home plate to the right-field foul pole that he claimed aided the Yankees’ sluggers, decided to mimic the dimensions at Municipal Stadium in 1964. After a few exhibition games, Commissioner Ford Frick ordered Finley to move it back to no less than 325 feet. (OTBP)

The Mule, And That Other Jackass.

In the wake of Johnson’s death, the A’s blindly steered through another futile, last-place season under absentee ownership before his estate put the team up for sale in December 1960. Buying was another Chicago business bigwig who, unlike Johnson, had a lot of brash ideas and a lot of brash things to say about the A’s, Municipal Stadium and baseball in general: Charles Oscar Finley.

Balding and graying with bushy eyebrows when he bought the A’s at age 42, Finley was a nonstop chatterbox of promotional suggestions and various opinions that would have led even Bill Veeck to respond, “Slow down, bro.” His hands-on approach and easy accessibility were initially embraced by Kansas City fans and politicians, as he did everything to wake up a dormant franchise—at least on an exterior level.

Finley took one look at Municipal Stadium and instantly saw a drab facility in need of a colorful makeover. He spent $412,000 of his own money—on a publicly-owned ballpark, no less—to spruce things up. Seats were repainted green and gold; his players’ uniforms would follow suit in 1963. Behind home plate, a mechanical Bugs Bunny clone wearing an A’s jersey popped out from underground hoisting a bucket of balls for umpires to use, while at the plate a compressed-air device nicknamed “Little Blowhard” was used to clean the dish and scare unsuspecting hitters. Because Brooklyn Bank, behind the right-field fence, was too steep to mow, Finley placed sheep there to take care of things and had them accommodated with a man dressed in biblical garb, complete with a tall cane, during games.

Continuing on the animal theme, Finley in 1965 opened a full-fledged zoo behind the seats on the third-base side. It included peacocks, green and gold pheasants, giant checkered rabbits, monkeys and rare albino kangaroos; one possibly true story circulated that players from the visiting Detroit Tigers fed the monkeys oranges dunked in vodka. When the zoo wasn’t enough, Finley brought on a mule called Charley O, frequently parading it around Municipal Stadium and even on the road—traveling by trailer and drawing crowds wherever it went. The joke went that Finley was more interested in his ass than his team.

Finley also made it unmistakably clear that, unlike Arnold Johnson, he would be no cushy affiliate of the Yankees. After complaining nonstop that the Yankees had an unfair advantage at Yankee Stadium because of its short, 296-foot distance down the right-field line, Finley took matters into his own hands and curled Municipal Stadium’s right-field wall to a similar distance to the foul pole with the same (three feet, eight inches) wall height. He got away with it for a few exhibition games before commissioner Ford Frick, citing a 1958 rule in which any new ballpark must have a minimum 325-foot distance down each line (Yankee Stadium, built in 1923, was grandfathered in), told Finley to scrap it. Finley abided, moved it back to 325 and, in jest, titled the area “One-Half Pennant Porch.” A year later, he took a different tact; instead of moving the fence back in, he put a canvas covering above the field to again mimic Yankee Stadium’s porch. This time, it stayed up right until the pregame festivities on Opening Day, when league officials again ordered it removed.

Promotional stunts under Finley weren’t just reserved for outside the lines. Late in 1965, the A’s paid tribute to the Kansas City Monarchs by giving legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, now 59 years of age, a cameo starting assignment in a late-season game against the Boston Red Sox. Before 9,289 at Municipal Stadium, Paige impressively showed that he still had some magic left in his arm; he allowed just one hit, a Carl Yastrzemski double, over three shutout innings.

For all of his unorthodoxy and creativity, Finley frequently flashed a dark side that bewildered and exhausted anyone who tried to reason with him. He fired seven managers in seven years at Municipal Stadium, and earned the wrath of his players; slugger Ken Harrelson called him a “menace to baseball,” while pitcher Lew Krausse told reporters, “If I have to play with that man again, I’ll quit baseball and find another job.” Finley even had the unwise temerity to hold a pregame ceremony bashing Ernest Mehl, the popular dean of Kansas City sportswriters who had championed major league ball to town, after he wrote a negative piece about Finley.

But Finley saved his biggest battles with city officials who owned Municipal Stadium. From the get-go, Finley haggled endlessly over the A’s lease with the ballpark, a debate that intensified early in 1963 when he found out that the newly-arrived Kansas City Chiefs of the American Football League were paying a single dollar per year to rent the facility. That the Chiefs were sharing 50% of concessions with the city while the A’s kept over 90% of theirs didn’t ease Finley’s temper. Still, he and the A’s got the $1/year deal as well—but the lease had been signed in the final hours before a turnover in the city council and mayor’s office. When the new council took over, they voided the deal because it required two-thirds of council approval. Finley had gotten six of nine votes; but the new council, now expanded to 13 seats, said it needed nine. This sly take on math theory left Finley—understandably, for once—livid.

For the next year, Finley raged. He wanted nothing to do with Kansas City or Municipal Stadium anymore, and threatened to move the A’s here, there and everywhere. To Atlanta. To Dallas. To Oakland. Even to the farmlands outside of K.C. city limits, sending front office staff out to negotiate with farmers wondering just what the hell was going on. He moved his team offices out of the ballpark and literally into the garage of scout Joe Bowman. Finally, in January 1964, Finley announced he was signing a two-year deal to play in Louisville, Kentucky. Fellow AL owners got together and told him, “No, you’re not.” They not only voted down the move, they gave Finley an ultimatum to agree on a Municipal Stadium lease deal within weeks, or be stripped of the franchise. Backed against the wall, Finley conceded, signed a four-year lease with no provision to bolt—and then still sued the city, claiming he inked the deal under an unfair threat of expulsion from the league. (A circuit court would eventually throw out Finley’s suit.)

While the tornadic Finley spun his ire at F5 strength, his A’s continued to lose, and badly—with a per-season average of 96 losses during Finley’s tenure in Kansas City. The A’s consistent showing at or near the AL basement was in sharp contrast to the inconsistency of Municipal Stadium’s field dimensions, which changed on an almost yearly basis—sometimes, radically. In Finley’s first season (1961), the wall to left and left-center was moved back, respectively, from 330 feet to 371 and 375 to 390; total home runs at Muni dipped below 100 for the first time. The A’s reduced the distance down the left-field line 20 feet in 1962, and another 20 feet a year later. In 1964, everything came in as Finley got his “One-Half Pennant Porch” fever—and home runs shot up to a ballpark-record 239; the A’s alone gave up 132, a major league record at the time. In 1965, the left-field wall was pushed back to 370 down the line and 409 to left-center—and if that wasn’t enough, the wall height was increased to 22 feet in left and 30 to dead center. When a 30-foot screen was added atop the 10-foot wall in right a year later, it became almost impossible to belt a home run; a mere 45 were hit that season, with the A’s collecting only 19 of those.

It became academic, when the A’s four-year lease on Municipal Stadium expired at the end of 1967, that Charles Finley would leave Kansas City. Not even the approval of the ambitious Harry S. Truman Sports Complex, which would yield separate new modern baseball and football facilities side-by-side, gave Finley pause to stay. The A’s left for Oakland, taking with them a batch of young, promising talent—Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter, Joe Rudi, Sal Bando—that would form the nucleus of a dynasty in the early 1970s. Kansas City fans were left with the memory of 13 frustrating years hosting the A’s at Municipal Stadium, with the team finishing below .500 every single season.

Baseball felt Kansas City’s pain and, three months after Finley said goodbye, gave the city a replacement ballclub in the expansion Royals, set to debut in 1969. In the interim, rectangular sports held sway at Municipal Stadium. As the A’s flunked out of town, football’s Chiefs were acing the test as a winning and, thus, popular alternative. Temporary bleacher seats were placed over left field and on Brooklyn Bank, increasing capacity size to nearly 50,000—and Chiefs fans constantly filled every one of them, watching a team that in 1969 went on to win the Super Bowl and give the young AFL a proud, pre-merger finale against the more established NFL. The Chiefs would remain at Municipal for two more seasons, with its most memorable game being its last: A double-overtime playoff classic on Christmas Day 1971 in which the visiting Miami Dolphins survived a 27-24 showdown over the Chiefs on Garo Yepremian’s 37-yard field goal.

A look toward left-center field at Municipal Stadium during a 1966 game against the Yankees. Providing a slight obstacle, the left-field light tower pokes out onto the left-field warning track. (Flickr—Missouri State Archives)

The Royal Rebirth.

Municipal Stadium’s fourth and last baseball tenant, the expansion Royals, began play in 1969 not so much as breath of fresh air but as a sigh of relief. There were no battles over the lease, no threats to move, no mules nor one-half pennant porches. Royals owner Ewing Kauffman—a local owner, for a change—prioritized progress over promotions, eschewing star names in the expansion draft and forging a strong farm system that would quickly bare the fruit of a highly respected organization by the mid-1970s. Fans sensed and bought into Kauffman’s discipline for future success, with over 7,000 season tickets sold for the inaugural season (the A’s, under Charles Finley, typically sold around 2,000). The first-year Royals drew 900,000 and finished with a 69-93 record—a respectable ledger for a first-year team, and easily the best of four expansion ballclubs in 1969.

With Royals (later renamed Kauffman) Stadium being built, Municipal Stadium served as a placeholder for the Royals, who hoped to spend only three years at the facility; delays at the new ballpark made it four. Given Muni’s lame duck status, little was done to spruce it up; the playing field and lighting system managed to maintain their reputations as among the majors’ best, and the outfield dimensions remained as the A’s had left it—though the Royals reduced the wall heights in left and right field back to 13 feet. As such, Municipal Stadium remained a pitcher’s park to the end—a notion that held true in the ballpark’s final event on October 4, 1972, when the Royals’ Roger Nelson pitched a two-hit shutout over the Texas Rangers before a surprisingly small farewell crowd of 7,329.

A victim of the wrecking ball in 1976, Municipal Stadium is today nothing more than a potpourri of memories that range from the magnificent to the maddening. In Monarch Plaza, a neighborhood park across the street from where the ballpark once stood, a series of monolithic plaques detail Municipal’s rich history and stories. Of the Negro Leaguers and minor leaguers who, through different circumstances, pined for a future presence in the glow of the game’s national spotlight. Of the major leaguers who pined, fruitlessly, to achieve contender status.

In a sense, Municipal Stadium was much like J.L. Wilkinson, the founder of the Kansas City Monarchs; modest and unpretentious, content to let the players get all the credit.

The Ballparks: Shibe Park In baseball’s landscape of horse buggies and wooden carts, Shibe Park emerged as the Model T of ballparks, a sparkling trendsetter that introduced steel and concrete to the game’s vernacular, beget rooftop entrepreneurs long before Wrigley and brought the game out of its lumbered, fire-cursed squalor. That it stood for generations while two tenants largely stank up the joint was a testament to its perseverance.

The Ballparks: Shibe Park In baseball’s landscape of horse buggies and wooden carts, Shibe Park emerged as the Model T of ballparks, a sparkling trendsetter that introduced steel and concrete to the game’s vernacular, beget rooftop entrepreneurs long before Wrigley and brought the game out of its lumbered, fire-cursed squalor. That it stood for generations while two tenants largely stank up the joint was a testament to its perseverance.

The Ballparks: Oakland Coliseum Correcting Gertrude Stein, there would be a ‘there’ there in Oakland once the Coliseum and adjacent arena opened their doors to a flood of interested tenants—including the A’s, who high-tailed from the Midwest and have called the laid-back facility home ever since, through great times and those awful, through latter-day stigmas of overflowed sewage and an Everest of a football expansion that has left a small but loyal fan base plugging their noses and covering their eyes.

The Ballparks: Oakland Coliseum Correcting Gertrude Stein, there would be a ‘there’ there in Oakland once the Coliseum and adjacent arena opened their doors to a flood of interested tenants—including the A’s, who high-tailed from the Midwest and have called the laid-back facility home ever since, through great times and those awful, through latter-day stigmas of overflowed sewage and an Everest of a football expansion that has left a small but loyal fan base plugging their noses and covering their eyes.

Oakland A’s Team History A decade-by-decade history of the A’s, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.