The TGG Interview

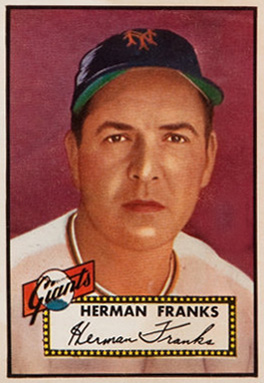

Herman Franks

“They say that I stole Brooklyn’s signs that day and I’ve never admitted to anything. And I never will. There’s been a lot of talk about it since ’51…When Bobby hit that ball it was one of the highlights of my baseball career.”

Herman Franks was a 1960s version of Al Lopez, a manager sharing the frustration of one second-place finish after another. But Franks enjoyed the satisfaction of being a part of Bobby Thomson’s famous home run that won the New York Giants the 1951 National League pennant.

A left-handed hitter who threw right-handed, Herman Franks broke into baseball with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League in 1932, but he was soon acquired by the St. Louis Cardinals and joined their large farm system. All you really need to know about his playing career was that he played primarily as a backup and finished with a batting average of .199 with three home runs in 188 games over parts of six seasons.

In 1949, Franks landed his first coaching assignment as an aide to Leo Durocher with the New York Giants. He was a member of two National League championship clubs (1951, 1954) and one World Series (1954) title team through 1955. According to author Joshua Prager in his 2006 book The Echoing Green, Franks played a critical role in Bobby Thomson’s famous pennant-winning home run in the 1951 NL playoffs—baseball’s Shot Heard ‘Round The World. According to Prager, Franks was stationed in the Giants’ center-field clubhouse at the Polo Grounds, their home field, stealing the opposing catcher’s signs through a telescope and relaying them through second-string catcher Sal Yvars (who was stationed in the bullpen) to the Giants’ coaches and hitters. When asked where he was when Thomson hit his home run, Franks said, in 1996, that he was “doing something for Durocher” at the time.

Whatever his role may have been on that day, Franks was known as a devotee of Durocher-style, win-at-any-cost baseball, including intimidation through flying spikes and brush-back pitching. Author Roger Kahn quoted Dodger outfielder Carl Furillo that Franks would poke his head into the Brooklyn clubhouse to taunt Furillo that Giant pitchers would throw at his head during that day’s game. Furillo, whose hatred for Durocher was so intense that he would engage Durocher in a fistfight in the Giant dugout filled with enemy players, said of the Giants in Peter Golenbock’s book Bums, “They were dirty ballplayers…They all wanted to be like Durocher, to copy Durocher. That Herman Franks, he was another one.”

Franks’ four seasons as manager of the San Francisco Giants from 1965-68 produced four frustrating second-place finishes. He then coached and managed off and on for the Chicago Cubs over an 11-year period. Although Franks compiled a poor record as a player, he notched a winning record as a manager—605 wins and 521 losses.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On his Role in the Bobby Thomson Home Run:

“They say that I stole Brooklyn’s signs that day and I’ve never admitted to anything. And I never will. There’s been a lot of talk about it since ’51. People don’t ever get tired of talking about it. I must have talked to this writer Prager more than 50 times. He even flew out here to Salt Lake City to interview me. Prager researched the hell out of that story, let me tell you. I read things in there I didn’t know. Sal Yvars has blabbed all over the place, but no one else has talked. Alvin Dark didn’t talk; I didn’t talk; Whitey Lockman wouldn’t say nothing about it. But, there are a lot of them still alive who did a lot of talking. When Bobby hit that ball it was one of the highlights of my baseball career.”

On his Relationship with Carl Furillo:

“Carl Furillo died a broken man; mad at the world. He got blackballed and was angry at the world. He couldn’t get another job in baseball and he blamed it on everybody but himself. He said a lot of bulls**t about me. In those days, we all jawed back and forth. The Dodgers had some tough pitchers in those days, Don Newcombe especially, and everyone threw at each other and knocked each other down all the time. You protected yourself. They were fiercely competitive in those days, Brooklyn and the Giants. Those two teams hated each other. In those days, there was a league rule—if you talked to the other teams’ players out on the field, you got fined. It’s not like today where the players chum around with each other; not at all. Now they go out to dinner with each other after the game; they’re all buddy-buddy.’ It’s just different now.”

On Steroids and Managing the Game Today:

“I am so sick of them talking about steroids. Barry Bonds is one of the best damn hitters I ever saw. He can flat-ass hit. And he set all those records when there was no law against them, right? A lot of this bulls**t wouldn’t go on if I was still managing. Maybe I couldn’t manage today’s game the way it is, I don’t know. I think the players are managing the managers today—agents telling the managers when they can pitch their pitchers, and all that kind of bulls**t. That wouldn’t go with me. And the money—the most I made as a manager was $125,000, with the Cubs, which at the time made me one of the highest-paid managers at the time. Now they get millions.”

On Bench Jockeying:

“Durocher was a helluva bench jockey, that’s well known. But, in those days you could holler from the bench. ‘Stick it in his ear,’ stuff like that. ‘Knock him down!’ You don’t dare say that today. Hell, I seen Leo walk up to the plate and get knocked down four straight times. He never complained. Everybody hollered at each other!”

On the 1965 Giants:

“The best team I ever managed, except I didn’t have a shortstop or a second baseman. We couldn’t make a double play. If I had had that I would have won the pennant all four years. We tried out a bunch of shortstops and second basemen, but we couldn’t find anyone to fill the holes there. We had five Hall-of-Famers on that team—Gaylord Perry, Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, Willie Mays and Willie McCovey. I taught Gaylord Perry how to throw that spitball; that’s what made him. We won 90 games three times during those four seasons and finished second each time. Today you win 90 games and you’re in the playoffs.”