The TGG Interview

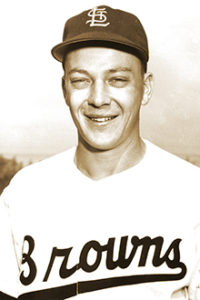

Joe DeMaestri

“They lined us up outside the bus and they were really mad. They were going to arrest (Vic) Power, but they said we could keep him out of jail if we could come up with $250. We took up a collection and gave them the cash. Eventually, it blew over because it didn’t hold any water in court. But it was scary—because they had pulled their guns and they meant business.”

Joseph DeMaestri, nicknamed “Froggy,” played for the Chicago White Sox (1951), St. Louis Browns (1952), Philadelphia/Kansas City Athletics (1953–1959) and New York Yankees (1960–1961). In an 11-season career, DeMaestri was a .236 hitter with 49 home runs and 281 RBI in 1,121 games played, and made the American League All-Star team in 1957. In the eighth inning of Game Seven of the 1960 World Series, DeMaestri took over at shortstop after Tony Kubek was struck in the throat by a bad-hop grounder hit by Pittsburgh’s Bill Virdon. DeMaestri was in the field when, one inning later, Bill Mazeroski hit his famous walk-off homer against Yankee pitcher Ralph Terry.

Joseph DeMaestri, nicknamed “Froggy,” played for the Chicago White Sox (1951), St. Louis Browns (1952), Philadelphia/Kansas City Athletics (1953–1959) and New York Yankees (1960–1961). In an 11-season career, DeMaestri was a .236 hitter with 49 home runs and 281 RBI in 1,121 games played, and made the American League All-Star team in 1957. In the eighth inning of Game Seven of the 1960 World Series, DeMaestri took over at shortstop after Tony Kubek was struck in the throat by a bad-hop grounder hit by Pittsburgh’s Bill Virdon. DeMaestri was in the field when, one inning later, Bill Mazeroski hit his famous walk-off homer against Yankee pitcher Ralph Terry.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On the 1951 White Sox:

“We were so much closer in those days as teammates, much more than how they are today. We were young guys without college backgrounds, because we all started playing ball right out of high school for no money. That was the way it was and we never knew different. In 1951, we trained in Pasadena, California and I made the Chicago White Sox. The manager was Paul Richards on that team and the guy was brilliant. He was always three innings ahead of everyone else. He was hard to get close to; he didn’t hang out with the players, that’s for sure. I swear you could be talking to him and if you turned around he would be gone. It never reached the point where you could sit down with him and talk friendly or get personal. But, he was an absolute genius as a manager, I believe. He was tough—he had no problem telling you if you weren’t playing well.”

On Nellie Fox:

“He came to us from Philadelphia the year before in 1951. At that spring training, he wasn’t playing well and they were planning to send him back. When he first started hitting he would sit in there like any other hitter. But, then one day he got a hold of one of those old bottle bats and started punching the ball, with his feet real close together. He changed his batting technique literally overnight. From then on, the guy was a .300 hitter. He wasn’t a flashy player, but he was as solid and reliable as they come. He was old school—he fielded ground balls at second base on one knee. Can you imagine if players did it that way today? But, that’s the way he was. He did not have a good arm or wasn’t fast, but he was tough and he played baseball that way.”

On Bob Derringer:

“He was a great cheater—he did everything you could to a baseball bat. He used to take the bats and file them down and flatten the hitting area—done to perfection. Plus he would groove them in spots so the ball would jump off that bat. He hit a lot of line drives that way. One night, they called him on it and he started arguing. He threw the bat away and grabbed another one, but he had done the same thing to all the bats. Back then, it wasn’t that big a deal. If he was doing it today, he would have been sidelined for some time, but back then they just made him throw the bat away.”

On Being Traded to the Browns:

“We lost 90 games that season, but it seemed more like 100. With the heat and humidity in St. Louis and those wool uniforms, it was terrible that summer. Those uniforms would get wet when you started sweating, and you felt like you were walking around in a burlap bag. Rogers Hornsby was the manager and he was universally disliked. His players hated him, but we finally got him good. We begged Bill Veeck, the owner, and asked him can you possibly get rid of this guy? We had a players meeting and right afterwards, Veeck fired him and made Marty Marion the manager. It was really hard to play for him. He wasn’t crazy about the black players and he sure didn’t like Satchel Paige. He was the only black player on that team at the time. Hornsby made things miserable for Satch and it finally came to a head. Hornsby tried to fine Paige $200 one day in spring training for being a few minutes late, but Satchel went to Veeck and that was the end of that.”

On Satchel Paige:

“Satchel Paige was a show all by himself. He was one of the nicest and funniest guys I’d ever met. He was a comedian and he loved pulling pranks. Some of those long train rides were a lot of fun, because Satch was a performer and we laughed. One day he went out fishing for catfish. They ran these fishing lines all across the river and baited them. I wasn’t familiar with that type of fishing, but that’s how he did it. They would come back the next day and pull the lines in, and they had huge catfish, three or four feet long. One day, Satchel had four of these big catfish and he threw them in the shower while we were all in there! That was the type of thing he would do. Then they got Satch a lounge chair one day, which he sat on in the bullpen. He had all his girlfriends coming to the game in St. Louis, it would be 110 degrees sometimes, and these ladies would be wearing these big fur coats and they had their booze hidden away in these little perfume bottles. And they’d slip ‘em over the fence to Satchel. It was usually gin, but sometimes it was vodka. And he’d sit there and drink more than a few. Then they’d bring him in and he would strike out the side. But that’s how Satch operated.”

On Bill Veeck:

“You couldn’t play for the nicest guy. He was such a player’s owner, just incredible. He used to take all of us with our families to picnics and events all the time. He lived there at the stadium—he had a place upstairs at Sportsman’s Park and that’s where he lived. Baseball was his life and I really enjoyed playing for him. He didn’t really do any of his stunts in ’52 when I was playing for him. The midget incident had happened the season before. But, he did do one thing I can remember. The tarps that covered the field had holes in them, and when the tougher teams like Cleveland, Boston or New York came to town, Veeck would let the field get flooded so the game would get rained out. He denied it, but I saw it.”

On the Philadelphia A’s Moving to Kansas City:

“We started hearing rumors at the end of 1954, but most of us didn’t really care. I heard about it on the radio actually. We were so happy, especially our wives. I sure didn’t miss those Philadelphia fans, they were absolutely brutal. The people were different there—just mean, for some reason. I remember the day that Gus Zernial got booed by the fans when he hurt his shoulder. They booed Santa Claus, poured beer on us—my wife stopped coming to the games, because she really had a tough time. Eddie Robinson bought a brand new convertible one year. We had a player’s parking lot and one night he came back to his car after the game and they had vandalized his vehicle. There was catsup and mustard all over it and that was our fans doing that. I heard a story that Connie Mack traded a player one time, because he said the Philly fans were going to kill him and I believe it. The Kansas City fans were an absolute delight, especially when compared to the ones in Philadelphia. They had six states to pull from for fans in Kansas City, and they could care less whether we lost 100 games or not—at least at the beginning! They came from all over and packed that place. It was like being reborn moving to Kansas City.”

On Vic Power:

“He was an incredible athlete, but he had his own style of playing baseball, which eventually became a problem. Vic covered first base on the move, but it got tiresome, because he was a moving target and difficult to throw to. The coaches told him about it all the time, but he could care less. The man was like talking to a brick wall. Good hitter, good runner—he had it all. One day it got really bad and led to a couple of errors. I’ve never done this before, but when the inning ended, I threw my mitt down in front of Lou Boudreau, our manager, and told him—you play with him because I can’t do it. Vic and I got along just great, but I knew he wasn’t going to change.

Power got into some trouble in Kansas City, because he was dating a white girl and it didn’t go over very well. There was no interracial dating back then, and the players had no trouble with it, but the team’s management wasn’t crazy about the idea. One day, we were at spring training in Florida and we were traveling after playing against the Tigers, if I recall correctly. The bus stopped at a gas station, which of course had black and white-only segregated bathrooms. When we stopped there, the blacks had to stay on the bus. We were sitting in the back of the bus that night, and we had a case of beer. After we finished a beer, we started throwing the empty cans out the window. We got to the gas station and the players were going to the bathroom, getting sodas, etc. So, Vic goes into the whites-only bathroom and we told him, you can’t do that. So, this young kid is running the station and we could see he was eyeing Vic like a hawk. Well, we get back on the bus and Vic had just bought a coke. There was a five cent deposit on the bottle and the kid told somebody that Vic hadn’t paid the five cents for the bottle. So, when Power heard what was said, he threw the nickel at the kid. The bus drove off and we thought nothing more about it.

We were halfway home, throwing the beer cans out of the window, and suddenly a cop pulls us over. He looks around and says we’re looking for the blackest player you have. We whispered to Vic, keep your mouth shut. The cop held us for about 20 minutes and eventually let us go, and we thought that was the end of it. Well, we hadn’t traveled another 10 miles and here they come again—an entire posse of some of the most red-neck cops you’d ever seen—many of them were plain-clothes policemen, more than a dozen of them. They were in T-shirts and they had .45s strapped to their wastes and they were looking for Vic. Evidently, the kid at the gas station had told them what had happened. They lined us up outside the bus and they were really mad. They were going to arrest Power, but they said we could keep him out of jail if we could come up with $250. We took up a collection and gave them the cash. Eventually, it blew over because it didn’t hold any water in court. But it was scary—because they had pulled their guns and they meant business. I can still see those cops today—sweating and cussing in their T-shirts and mad as hell!”