The TGG Interview

Tony Malinosky

“I tell the guys I was a better than average ball player and that’s all. In my own heart, if I hadn’t gotten banged up, you would never have heard about a guy named Pee Wee Reese.”

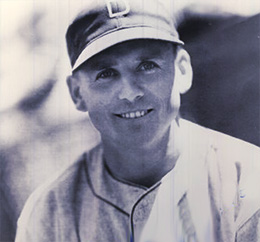

Tony Malinosky during his one and only major league season, with the 1937 Brooklyn Dodgers.

When a player named Dick Stuart died three days before I was scheduled to interview him in 2002, I decided to get a list of the oldest living players. “These are the guys whose history I should capture,” I reasoned. “Before they leave the planet and we lose their memories forever.” So, I found the list of the oldest living players on the Internet and began searching for their contact information. At that time, the oldest player was a gentleman named Rollie Stiles. I interviewed him and the project began. On January 22, 2009, Tony Malinosky replaced Billy Werber as the oldest player on the planet and I began tracking him down.

Living in Oxnard, Calif., I found Malinosky’s phone number and called him. His caregiver, a woman named Shelly, answered the phone. I explained my purpose and told her I’d like to come down to interview Malinosky. “A reporter from San Francisco wants to interview you,” she said to Tony. “You tell him to bring his wallet,” he said. Shelly turned to me on the phone and said, “Do you normally pay these retired players for your interviews?” “Not normally,” I replied, “But I am going to take up at least one hour of his time, so how about I give him $100?” Since he was 100 at the time, I thought it was fitting. Shelly turned to Malinosky and said, “He says he’ll pay you $50 and not a penny more.” “No, it’s not enough,” was Tony’s retort. Shelly starting reasoning with him at that point. “It’s $50 we didn’t have two minutes ago, Tony. It’s enough for food and beer for almost the whole week.” After a pause, he said. “Okay, you’re right, I guess. It’s money I didn’t have before, so set it up. But no checks!” And that was the beginning. The following day, I drove from San Francisco to Oxnard, stopping only for coffee and an In-N-Out burger. Here are some excerpts from the interview, which was conducted on October 15, 2010. It might have been one of the last in-depth interviews anyone did with Malinosky, because he died four months later.

Malinosky was a third baseman and shortstop who played 35 games for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1937, before a serious injury abruptly ended his baseball career. Born in Collinsville, Illinois, Malinosky attended Whittier College, where he played baseball and was a classmate of future U.S. President Richard Nixon. The Pittsburgh Pirates signed Malinosky to his first professional contract, and then sold his rights to the Dodgers in 1936. During World War II, he was drafted by the United States Army, with which he saw combat in the Battle of the Bulge. The Los Angeles Dodgers honored Malinosky at Dodger Stadium in 2009, on the occasion of his 100th birthday.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On his Early Years:

“I was five years old when I first started playing baseball. My parents were immigrants from Lithuania, so they knew nothing about baseball. I started telling people at a very young age that I was going to be a baseball player. Babe Ruth was my hero, just like a lot of other kids. In high school, college and in the war, I never wavered or flip flopped about becoming a professional baseball player. I didn’t want to be a singer like Sinatra, I didn’t want that. To be honest, I would have played for nothing. I don’t need money now really—that monetary crap never concerned me. Today, I don’t need a lot. I like to have a beer every day around cocktail hour, usually with a hardboiled egg or two.

When I was six, people started noticing that I was pretty good. In high school, I was the captain of the baseball team and same at Whittier College. My wife Viola put together a scrapbook of all my accomplishments. She was my high school sweetheart in 1928. We were married for 64 years, can you believe it? Now, these guys change wives or bed partners every couple years. I lost her 11 years ago and she never got to finish the scrapbooks, because she was sick before she passed. If someone wrote a book of my life, I know it would be a bestseller, because so many unbelievable things happened to me. I went to El Monte High School, a very small school with about 300 students, and we won almost all of our games. We went to the CIF playoffs and got beat in the championship game. A guy by the name of Rube Ellis (a former MLB player) was the coach at Whittier College, and he recommended me to the Pirates. A scout named Art Riggs signed me to a Pittsburgh big league contract; that’s where I started my career. I was no superstar; I wasn’t anything out of the ordinary.

Tony Malinosky (left), shortly after turning 100, poses with This Great Game’s Ed Attanasio.

The only reason that people are even remotely interested in me and why you’re here is because I lived to be 100. You get to that 100 mark and people like you start coming around. I replaced Billy Werber and right after he died, I started getting the fan mail. They asked me to sign this, sign that—lots of exposure. And I tell the guys I was a better than average ball player and that’s all. In my own heart, if I hadn’t gotten banged up, you would never have heard about a guy named Pee Wee Reese. He’s the fella who succeeded me there, but in my opinion…of course, I thought pretty highly of my abilities and I still do.”

On his late buddy, Richard Nixon:

“We knew each other while attending Whittier College, we were classmates. We weren’t buddy-buddy, but good enough to be friendly. We were in the same class, and several of our other classmates got into politics, although Nixon went further with it than the rest of the bunch. He was not an athlete, but he went out for football. He made the squad, and the most action he saw was when they played scrimmages. As far as a person, I have no qualms about the guy. I don’t know if he was brilliant or not, but he must have been pretty good to talk his way up to the top. Many years later, he insisted that I start calling him Mr. President, but I wasn’t doing that. I called him Dick and he didn’t like it, but that’s just tough, now isn’t it? I’m an informal person all the way down the line.”

On his 1935 Salary:

“These players today get more money playing one inning than I made my entire career. Do you know how much the Brooklyn Dodgers paid me back then? Four hundred bucks a month, can you imagine that? Shoe shine boys wouldn’t work for that today! 400 bucks a month and they whined about paying me that. We lived on White Castle hamburgers and coffee back then because we were sending our checks home. Those burgers were 10 cents, but they were real small. I’d buy five for 50 cents and that was a major league dinner for me.

People look at me and think, oh—Tony Malinosky, former major league player—we can take him up for a pretty good lick. That’s a lot of bull! I get fan mail all the time. I sign their stuff and I send it back to them, without asking for a nickel. And what do they do? They take the autograph and sell it on eBay. They charge people for it. They make money and I give it to them free. And that’s why I’m going to give this an abrupt end, because I’m tired of people trying to make money on my name. You might just say I’m pissed off and that’s the whole shabang.”

On his Longevity:

“How did I do it? It’s simple. All you have to do is keep breathing. And have a good doctor to help you along. It’s called continuous breathing. And I also tell people luck is part of it. To live that long, without getting in a serious accident, in either the war or anywhere. It’s just plain luck. I’m so tired of that question. What else do you want me to say? It’s a dumb question. All my friends from college, my baseball teammates, and my army buddies are long gone but me. So what do I do about it? I get old, what the hell can I do? Next question.”

Going to Opening Day at Dodgers game to celebrate his 100th birthday:

“I wasn’t going to go. In fact, I was refusing to go for quite some time and then a writer and friend of mine, Doug Williams, persuaded me that I should go. I didn’t enjoy it at all. The only one I knew there was Tommy Lasorda. I don’t have too much confidence in the success of the Dodgers. I don’t like the way they do things, even though I was a member of their organization at one time. Everyone thinks they’re my favorite team, but they’re not favorite team. I enjoy a well-played game that’s competitive, but the Dodgers have never been my favorite team.”

On Sliding Late in the 1970 Season:

“I had a lousy July, batting around .200 and I was striking out a lot. That’s when they started messing with my stance and wanted me to use a heavier bat, thinking that I would start hitting more to right field. August wasn’t any better, even though I was leading the team in hitting and homers. During the offseason they traded Sizemore to the Cardinals, so I figured I was going to be the Dodgers’ starting second baseman in 1971.”

On his old friend Tommy Lasorda:

“He spews out so much B.S., that guy. When he managed the Dodgers, he kept referring to the “big Dodger in the sky.” What a bunch of…. He’s talking to grown men this way, not high school kids. They don’t go for that crap. They’re out there for the dough, instead of worrying about the big Dodger in the sky or the little Dodger down below! It doesn’t mean I hate the man, but these guys are getting paid for doing nothing! When I was busting my ass for the Dodgers, they paid me nearly nothing.”

On being Drafted into the Army:

“I was barely 30 years old, so I figured I was fairly safe, but they drafted me anyway. I saw some action, that’s true. And I sure didn’t like getting my fanny shot at it, be certain of that. Then, I was in the Battle of the Bulge, in the infantry. They gave me the choice of going to Officers Training School, but I didn’t want that. For one, I felt I was too old for that. So, I ended up in the infantry and that meant I saw a lot of action. I didn’t like the experience at all. I considered my days in the Army lost days for me. Some of the baseball players who got drafted had a cushy time, playing baseball and doing nothing else. But, as a common journeyman, they didn’t do that for me. So, I ended up at the Battle of the Bulge. We were the outfit that the Germans hit first. We had just gotten over there, and they put us in what they call a “soft spot” or a “quiet zone.” Patton and his 3rd Army were down south—that’s where they were. But, our “quiet zone” wasn’t exactly quiet. The Germans evidently knew about it, because they came right through our outfit. We lost 8,000 men in one skirmish. That’s right—8,000 men—either killed or captured. I pretty much lost all my friends over there.”