THE YEARLY READER

1948: The Greatest Show in Cleveland

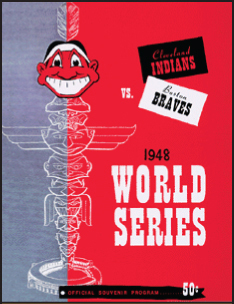

The Cleveland Indians, under the wildly colorful and successful ownership of Bill Veeck, reach their first World Series in 28 years and match up against the Boston Braves, making their first Series journey in 34 years.

Cleveland Stadium is packed to its 80,000-seat capacity for the first game of the 1948 World Series. It was hardly the first time during the year that the facility was filled up. (Associated Press)

When Bill Veeck began his first day of work as owner of the Cleveland Indians in 1946, he tore his office door off the hinges and threw it away. He wanted anyone who walked by to feel welcome to come on in.

A maverick promoter, the young, gregarious Veeck carried this philosophy to the front gates of Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, a monstrous facility that until his reign had been a constant sea of empty seats. Veeck’s non-stop parade of gimmicks, giveaways and gratuities grated on the lords of baseball, who to a man were convinced that Veeck had turned his organization into a freak sideshow that devalued the focus on the game. But in 1948, 2.6 million clicks through the turnstiles later, Veeck proved them all wrong.

For all of his theatrics, Veeck’s most potent sell remained between the lines. Invigorated by the record attendance, the Indians racked up their first American League pennant in 28 years and headed into a World Series against a Boston Braves team that also understood the importance of winning both on the field and at the ticket booth.

Promotions and special days were nothing new to the majors and neither was Veeck, who worked with his father in the Chicago Cubs’ front office during the 1930s. But Veeck pounced on the potential of marketing the game like no one before him, devising new and constant ways to bring the fans in. In 1941, the 27-year-old Veeck bought his own team—the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association—and applied his gift of sideline spectacle to the proceedings. The locals responded, and so did the players—winning three straight AA titles under Veeck’s rule.

Cleveland owner Bill Veeck witnesses the signing of ace pitcher Bob Feller to a contract for the 1948 season, a year that would represent a crossroads for the right-hander; he won 19 games and led the AL for the seventh and last time, all while the velocity on his once-breakneck fastball began to wane. (The Rucker Archive)

After serving three years in World War II—where he lost his right leg in an accident—Veeck led a group that included comedian Bob Hope and bought the Indians for $1.6 million in 1946. His showmanship continued in Cleveland, spiking each game with some sort of attraction beyond the pairing of two baseball teams. The Indians finished a lowly sixth in the AL that year, but drew over a million fans for the first time. They improved to fourth in 1947, drawing 1.5 million—second only to the New York Yankees.

The tightly knit AL pennant race of 1948 gave fans everywhere the incentive to come through the gates. Five teams were in serious contention after the All-Star break, and on August 3, four teams listed dead even for first place. There were the defending champion Yankees, carried mostly on the backs of Joe DiMaggio (batting .320 with 39 home runs and 155 runs batted in) and Tommy Henrich (.308, 25, 100). There were the Boston Red Sox, with Ted Williams forging his way to a second straight batting title (at .369) and Vern Stephens, rescued from the St. Louis Browns, knocking in 137 runs. There was the surprise of the pack, the Philadelphia Athletics, giving Connie Mack a rare burst of overachievement in his 48th year of managing. And then there was Cleveland.

The success of the Indians was largely attributed to a roster loaded with players suddenly playing above their heads. Former Yankees second baseman Joe Gordon, discarded from New York following an anemic 1946 campaign, revived himself to lead the Tribe with 32 home runs and 124 RBIs. Also reborn, for the moment, was veteran third baseman Ken Keltner, establishing career highs with 31 homers and 119 RBIs. And the Indians’ starting rotation included a startling effort by rookie knuckleballer Gene Bearden, a survivor of a fractured skull in South Pacific warfare who won 20 of 27 decisions and led the AL with a 2.43 earned run average.

BTW: After a strong start to his career, Ken Keltner since 1941 had averaged .270 with nine homers a season coming into 1948.

The most impressive performance on the Indians came from shortstop Lou Boudreau, the only player-manager left in the majors 10 years after the trend had exhausted itself. Completely leading by example, Boudreau batted .355—second only to Ted Williams—while setting career highs with 18 homers, 106 runs knocked in and 116 scored. All this, and he struck out just nine times for the entire season. Throw in his leadership abilities and his defense, for which he led all shortstops in fielding, and Boudreau was the no-brainer choice as the AL’s Most Valuable Player.

BTW: Boudreau had been shopped around by Veeck before Opening Day, leading the Cleveland owner to later state, “Sometimes the best trades are the ones you don’t make.”

There was hardly a dull moment all year at Cleveland Stadium. While the team was the top attraction, there were plenty of sideshows with fireworks, Vaudevillians and acrobats. Veeck attracted more women through the gates by giving away free orchids and nylons, and set up a nursery inside the stadium for parents to drop off their toddlers. He claimed to insure the handsome face of utility infielder and aspiring actor Johnny Berardino for a million dollars. And when a fan named Joe Earley wrote to Veeck asking why the Indians never held special nights for the common fan, Veeck responded with Good Old Joe Earley Night.

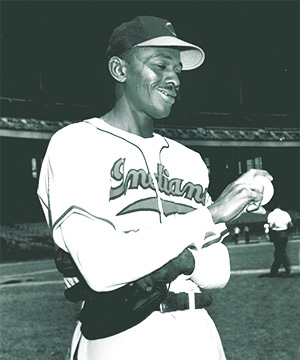

Fortysomething-year-old Negro League legend Satchel Paige lived up to the bluster and showed the majors what they’ve been missing for the last 20 years when he signed on with the Indians in June and went 6-1 with a terrific 2.48 ERA. (The Rucker Archive)

On the field, Veeck made a sensational midseason move by bringing on Negro League pitching legend Satchel Paige, following outfielder Larry Doby as the team’s second African-American ballplayer. At fortysomething, many thought Paige’s arrival was another Veeck publicity stunt. But he was quite serious about Paige; the turnstiles were clicking enough already. The doubters were made to believe when Paige hurled two shutouts against the Chicago White Sox in a 10-day span in August, on his way to a 6-1 record and a 2.48 ERA. It pained to imagine how brilliant Paige might have been in the majors during his prime—if only he had been allowed to participate.

Unexpected drama added itself to the menu during the pennant race in September when pitcher Don Black, after wildly striking out at the plate, collapsed to the ground with a cerebral hemorrhage. Briefly near death, Black eventually recovered but was done with the game; yet Veeck was on top of the matter, holding a benefit ceremony before a game with the Boston Red Sox a week later that drew 76,000 fans and raised $40,000 to help pay off Black’s medical bills.

After surging through September to catch up with the Red Sox and Yankees, the Indians could have clinched the pennant on the season’s final day but lost at home to Detroit—setting up a tie-breaking matchup the next day with the Red Sox, who had just eliminated the Yankees. It was Lou Boudreau to the rescue; the skipper went 4-for-4 with two home runs as the Indians gained entry to the World Series with an 8-3 victory at Fenway Park.

The Red Sox’ loss put an abrupt end to the dream of all-Boston World Series. Yes, it was true: The Boston Braves had made it to the Fall Classic.

Since their only previous visit to the World Series as a miracle entrant way back in 1914, the Braves had re-cemented themselves as Boston’s “other” baseball team, especially after Tom Yawkey remade the Red Sox as a spirited gate attraction starting in the mid-1930s. That the Braves hadn’t been in pennant contention for three straight decades didn’t help. It all began to change in 1946 when local contractor Lou Perini, one of a triumvirate of investors who bought the team in 1941 and now its president, hired manager Billy Southworth, the pilot for the St. Louis Cardinals’ wartime juggernaut. Instantly the Braves began to respond for the better; in 1946 they enjoyed their first winning season in eight years, and in 1947 stepped up to third place with their best record since 1916.

Chief Wahoo, baseball’s most controversial caricature, gets prominent face time on the cover of the 1948 World Series program handed out at Cleveland.

The Braves were a fine balance of hitting and pitching, leading the NL in both batting and earned run average. Five regulars hit over .300, including rookie shortstop Al Dark (at .322); reigning NL MVP Bob Elliott continued as the team’s slugger, knocking out 23 home runs with 100 RBIs. While there was consistency in the everyday lineup, the starting rotation relied more on the star duo of left-hander Warren Spahn and right-hander Johnny Sain. Spahn sputtered after a terrific 1947 campaign but still won 15 games; Sain picked up the slack, leading the NL in wins (24) innings (314.2), complete games (28) and authoring the third-best ERA at 2.60. The patched-up remainder of the pitching staff was such that the reliance on Spahn and Sain led to the now-famous refrain, “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain.”

BTW: Spahn and Sain paired up to start 15 of the Braves final 22 games of the regular season, winning 11.

While the Braves lacked the audacious marketing traits of Bill Veeck, they were quite progressive compared to the other clubs, thanks to public relations guru Billy Sullivan—the future owner of the NFL’s New England Patriots. The team had never drawn more than a half-million fans in any season before Perini took over; in 1948 it brought in just under 1.5 million, nearly equaling the Red Sox’ gate at Fenway.

The two tribes that were the Indians and Braves initiated the World Series with a stellar pitching duel overshadowed by controversy. Bob Feller and Johnny Sain traded zeroes throughout much of the day, and it appeared likely to stay that way in the bottom of the eighth when Boston pinch-runner Phil Masi looked dead at second base on a pick-off attempt by Feller. Umpire Bill Stewart thought otherwise, and Masi would score the game’s only run on a two-out single by Tommy Holmes. The news photography of the play would later prove that Stewart blew the call—and blew it badly.

The Indians overcame the miscall and took charge over the next three games, as starters Bob Lemon, Gene Bearden and Steve Gromek each went the distance to allow the Braves a total of two runs in winning all three. Anticipating a Series victory with Feller back on the mound for Game Five, a crowd of 86,288—the largest gathering yet for a major league ballgame—crammed Cleveland Stadium. But the Braves got their bats back in order and pounded the Indians, 11-5. The loss only deprived Cleveland of winning the Series at home; the Indians recovered for Game Six at Boston, as Lemon and Bearden combined to finish off the Braves, 4-3.

Conquering All but the Mendoza Line

With a .199 team batting average, the 1948 Indians became one of just five teams to win a World Series despite hitting below the .200 mark.

The Indians took their second world championship—and their last to date—despite hitting just .199 as a team. With nearly 240,000 tickets sold for three World Series home games, the Indians drew a then-unheard-of figure of nearly three million fans for 80 home dates in 1948.

Bill Veeck would continually rise and fall through the next 30 years in baseball, but the complete success of his 1948 Cleveland Indians, on the field and off it, made for his finest hour.

Forward to 1949: Casey at the Helm The zany Casey Stengel silences the critics and embarks the New York Yankees on a long and fruitful dynasty.

Forward to 1949: Casey at the Helm The zany Casey Stengel silences the critics and embarks the New York Yankees on a long and fruitful dynasty.

Back to 1947: The Arrival of Jackie Robinson Baseball’s color barrier is knocked down, but not without intense prejudicial resistance.

Back to 1947: The Arrival of Jackie Robinson Baseball’s color barrier is knocked down, but not without intense prejudicial resistance.

1948 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1948 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1948 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1948 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Chuck Stevens recalls Jackie Robinson, and his experience being the first major leaguer to get a hit off the great Satchel Paige.

Chuck Stevens recalls Jackie Robinson, and his experience being the first major leaguer to get a hit off the great Satchel Paige.