THE BALLPARKS

American Family Field

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

(iStock)

Beer may have made Milwaukee famous, but it was County Stadium in the 1950s that showed America that baseball could play better there than anywhere else. A half-century later, American Family Field—originally entitled Miller Park—rekindled the torch and ensured its fans that the good times have indeed returned to the city with its heart restored to the National Pastime.

It begins with the tailgating. Pick-ups, SUVs, even sedans all settle into a parking lot that’s about to turn into a concrete patio. Unfolding chairs and tables are accompanied by ice-cold beer and hot brats sizzling on hibachis. Everyone’s talking, laughing and having a great time. Two hours before the first pitch at American Family Field, the party has already started for thousands of Milwaukee Brewers fans.

Spare us those downtown ballparks choked by surrounding chic restaurants, say these hungry pregame revelers. Here, removed from the hi-rises, asphalt gets the thumbs-up.

At a time when baseball teams rushed to clone one another on building nostalgically-themed ballparks fashionably snuggled into midtown blocks, American Family Field emerged as the anti-Camden Yards. It’s not because of its aesthetics. The ballpark is clad in a mix of red brick and arches typical for the retro era; even the unique, fan-shaped retractable roof, so often cited as being paradoxically modern by contrast, packs a reminiscent twinge of days of future past—appearing as a super-sized version of Jules Verne’s Nautilus sea vessel in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

What does set American Family Field apart from its major league cousins is its setting. It was built in the shadows of County Stadium, its predecessor from an era when sports facilities surrounded by endless parking on city outskirts was the trend. Urban planning? American Family Field never heard of it. The ballpark didn’t conform to the grid; the grid conformed to it, as an adjacent freeway was forcibly curled around to accommodate the venue’s footprint. And pleas from many to engage American Family Field within a mixed-use environment was strangely denied as the City of Milwaukee chose to develop an expanse of open space to the ballpark’s immediate east, in the Menomonee River Valley, as an industrial wonderland. So instead of a Hilton, Rock Bottom Brewery and Urban Outfitters, the doorstep to American Family Field consists of Charter Wire (steel), J.F. Ahern Co. (mechanical) and Caleffi North America Inc. (heating). Not exactly eye candy to tempt arriving or departing baseball fans.

To be truthful, Brewers fans don’t care about American Family Field’s surroundings. All they want is a parking space, room to cook, eat and drink, and a ticket to get into Milwaukee’s biggest and most distinguished structure to watch their beloved team. Without it, a rotting County Stadium couldn’t have cut it and the Brewers would be long gone. If you don’t believe that, there are plenty of aging Wisconsinites who will quickly tell you about Milwaukee’s turbulent history of major league ball in the last half of the 20th Century.

From Braves to Brewers to Almost Nothing.

The city built County Stadium on spec in the early 1950s, and was rewarded for it by seducing the Braves into town. The team was enthusiastically supported, won two pennants and a World Series. And then, just 13 years after they arrived, they were gone—seduced again by another new stadium in a larger city (Atlanta). Distraught local officials, led by Bud Selig—a young, bespectacled, nerdy-looking car salesman—looked for a replacement. Ninety miles south in Chicago, the White Sox were curious enough to let Milwaukee host 20 games between 1968-69—and were impressed to see average attendance nearly three times that of what they were scraping in at Comiskey Park, proving that Milwaukee fans still had a thirst for something other than beer. Rumors accelerated on a White Sox move to Wisconsin—but Selig and Co., rather than try to pry an established franchise, instead went after the low-hanging fruit in 1970 when they purchased the fledgling, bankrupt Seattle Pilots and relocated them to Milwaukee.

The Brewers-nee-Pilots gradually settled into a stable and well-received existence at County Stadium, occasionally drawing just south of two million in annual attendance—a figure to be proud of in the majors’ smallest market. But as the Brewers strengthened in the standings and at the gate, County Stadium weakened in the eyes of Selig. The facility was pushing 40 years of age, and it wasn’t getting any younger. Compounding Selig’s concerns was the hyperinflation of major league salaries via modern free agency, and the early moves by teams to begin building revenue-driven, baseball-only facilities. Selig couldn’t do anything about the former, but certainly could with the latter.

Of course, no one said it was going to be easy.

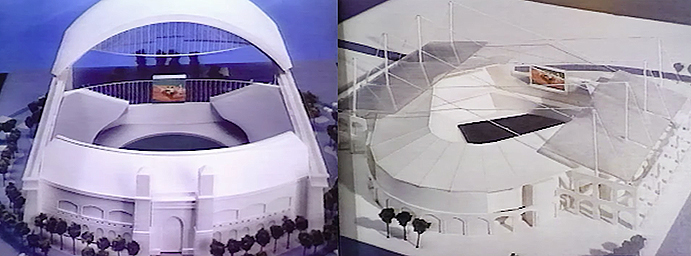

Initial talk of rejuvenating County Stadium gave way to the idea of a brand-new ballpark. Potential sites were all over the place, from downtown to Westown to the lakefront before settling on County Stadium’s backyard—where Selig was hoping to build all along. Separate discussion centered on whether to put a lid on a new ballpark to ensure out-of-town fans that the games would go on, and that they wouldn’t shiver along with everyone else in early- and late-season contests. To that end, Los Angeles-based architect NBBJ provided three models, each containing a different retractable roof concept. One involved a sliding arch a la Seattle’s T-Mobile Park. Another used two flat panels pulled upward to create a tent-shaped covering. The third concept would prove to be the charm: A fan-shaped enclosure, consisting of numerous panels cascading in from perpendicular sides to create a cover in perfect conformance with your average pizza-sliced baseball field. It was graceful and unifying all at once.

Politicians determined that a statewide sports lottery would pay for the new facility—but they wanted voters to have a say in the matter. And say they did, loudly and clearly; by a 64-36 margin, they overwhelmingly killed the idea in an April 1995 referendum. It didn’t help that the vote was ill-timed as baseball fans had stored up eight months’ worth of anger over the just-ended work stoppage, fomented on the owners’ side by Selig—pulling double duty as Brewers owner and “interim” baseball commissioner.

Having struck out with the lottery, State and local leaders circled back and brainstormed on a different funding path toward a ballpark—this time, without voter approval. What they came up with was a plan in which five counties making up the greater Milwaukee metro area would impose a 1/10th-cent sales tax increase to help finance the venue. This time, the power of approval would be given to the State legislature. The lower Assembly barely signed off on the bill, sending it on the Senate—where the real drama awaited. On October 7, 1995, endless debate seemed to yield no movement on a 16-15 edge against the bill—but then, in the early morning hours, Racine Senator George Petak suddenly developed a change of heart and switched his no vote to yes. Yet a final tally couldn’t be taken; one senator, Joe Wineke, couldn’t be found for hours. His colleagues, using a touch of political melodrama, readied to file a missing person’s report before he was discovered hidden away within the building, catching a nap.

George Petak’s deciding vote saved the Brewers from leaving Milwaukee, but he couldn’t save his job. Seven months later, district voters enraged over his last-minute switch made him the first legislator in Wisconsin’s 148-year history to be recalled.

Before American Family Field’s fan-shaped retractable roof was okayed, other options were considered including a sliding arched roof (left) and a tent-like design (right).

The $50 Million Hot Potato.

The ballpark budget called for the sales tax increase to cover $160 million of the facility cost; the Brewers would kick in the other $90 million. Bud Selig covered $40 million of their end by selling the ballpark’s naming rights to Miller Beer, thus the venue’s original name of Miller Park. The ballpark deal called for the other $50 million to come through a loan from the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority (WHEDA), a “quasi-public” agency that typically dealt with affordable housing and small-business loans. But when WHEDA looked through the Brewers’ financial books, it was stunned to see that not only did the Brewers not have the money, they didn’t even have the collateral to secure a loan. WHEDA went back to the State Capitol and reported that it could not, in good conscience, provide the Brewers with a loan it wasn’t sure could be repaid.

Selig was livid. He demanded that the Southeast Wisconsin Professional Baseball Park District (SEWPBPD), the newly-formed ballpark board, provide the loan. The board itself became livid, rejected the suggestion and told Selig he had to come up with the $50 million—or the ballpark would be dead before the first shovel could be plunged into the ground.

Rushed into scramble mode, Selig did receive one offer from the City of Milwaukee to cover the full $50 million—but only on the condition that the new ballpark be placed downtown. Selig stubbornly shot it down, saying that the lack of open space would cripple the Brewers’ pregame tailgating tradition. Months passed with no further offers of financial assistance thrown toward the Brewers.

By mid-June 1996, as the Brewers were hosting the Oakland A’s, a deflated Selig sat below the stands in his humble County Stadium office, wondering if he and his team were at the end of the line in Milwaukee. He then received a phone call from Brewers broadcaster Bob Uecker, who pleaded with him to come to the booth and address the situation. Selig declined, but Uecker persisted. Finally, Selig agreed, went to the booth and bared his painful soul over what was needed to keep major league ball alive within the city.

From this conversation, a domino effect began; Selig strolled through the stands, gave one quick interview after another with local media as surrounding fans caught on and spread the word; before long, the entire crowd of 14,000 began chanting “Bud! Bud! Bud!” to such distraction that the game on the field was held up. The Selig Effect became viral; the next day, “Build it Now” became a brand as everyone in town seemed to hop on board to stir up support for the $50 million and, ergo, the ballpark. Within two weeks, Selig got his money as various grants from the city, business community and local foundations piled up on his behalf. Miller Park was back on.

It’s a Warehouse—no, it’s a Spaceship—Wait, it’s a Sea Monster!

Long before Miller Park was given the green light, architects were hard at work on developing a look and feel of the venue that would hold all the way to the blueprint stage. Ambition was pared down; early renditions showed a small lake behind the outfield end of the ballpark, and a vibrant picnic area along the nearby Menomonee River that fans could use as a tailgating option. Neither made the final cut.

Take one quarter of a pie chart and you have the basic shape of American Family Field; the first- and third-base sides of the structure run in straight lines 90 degrees apart from one another, connected together by the circular end. Behind home plate, another quarter-circle segment of the structure breaks forward in palatial fashion, adorned with seven tall brick-red arches with touches of warm white and blue stone accents.

The external entry is buffeted at its left end by a clock tower to give the ballpark a touch of Milwaukee class. “(The tower) was an interesting way for the name of the ballpark to become exposed, and that was the thing that Miller Beer really turned on to, it felt like a tower,” said NBBJ lead designer Dan Meis. “Milwaukee has church steeples and clock towers just about every block.” Meis also cited Milwaukee City Hall, with its arches and ice-blue roof toppings, and Lake Front Station, the city’s extinct train depot, as influences on the ballpark—though the steep A-frame roofs iconic with both buildings aren’t leveraged into the design.

The entry façade is so inviting, it screams for an equally formal rotunda on the inside, like Brooklyn’s old Ebbets Field or newer yards such as Seattle’s T-Mobile Park and New York’s Citi Field. Alas, there is none; once through the door, you basically just spill onto the main concourse.

Meis’ biggest concern with the ballpark design was how to reconcile a 19th Century-style edifice with a 21st-Century retractable roof. His clever solution was to add old-style industrial arches upon the tops of the five moving panels and disrupt any immediate impression of the roof mimicking a futuristic spaceship like Toronto’s Rogers Centre. There’s no doubt that the arches add character to the roof; when it’s closed, there’s a sense that the panels, converging together toward the front gate with the arches appearing as sharp dorsal fans, are descending upon arriving visitors like a giant sea monster or, worse, the mother alien. To some, it can be an intimidating sight.

Clash of styles? A decorative clock tower stands in the foreground against American Family Field’s massive, more modern retractable roof structure. Architectural pundits criticized the ballpark’s amalgamation of past and future, but the placement of old-style arches atop the roof gives it less of a space-age look. (iStock)

“Get Me Out of Here!”

Harmonizing the roof with the lower structure aesthetically wasn’t the biggest challenge; building it was. Each panel had to be pieced together, segment by segment, atop the ballpark. Many cranes were involved in the process, but to lift the heavier parts, the mother of all cranes had to be called in.

The Lampson Transi-Lift 3, more affectionately known as “Big Blue,” was the largest crane in North America; there were only four others like it around the world. You couldn’t just wheel it in pre-assembled; it took seven weeks, 25 people and 150 truckloads of materials to put it together outside of Miller Park at a cost of $10 million. To keep it upright while lifting its maximum weight, Big Blue needed to be balanced by 1,150 tons of counterweight. The crane’s boom, emanating high into the sky from the cab, rose 467 feet—and even that wasn’t enough for Miller Park’s roof, so they attached a 100-foot extension to it, forcing Lampson to file an FAA permit so that low-flying planes could be alerted to the crane’s presence. Big Blue was a conversation piece to rival the ballpark itself.

In July 1999, nine months before Miller Park’s target opening date, Big Blue was ready to perform its 10th of 29 lifts—or “picks,” as they were called in the construction industry—of the ballpark’s roof panels. Late-afternoon winds gusting to nearly 30 MPH prompted debate among the various parties in charge, including Lampson and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of America, which designed and constructed the roof. No one bothered to do a “wind-sail” calculation to determine whether the pick should proceed, because the assumption was that it someone’s else responsibility. Additionally, there was pressure to move forward since Mitsubishi’s contract with the ballpark board called for penalties if the project wasn’t completed on time. The pick went on.

As a section of skeletal steel was hovering high above the first-base side of the structure, a series of bangs echoed loudly throughout the site; it was Big Blue’s king pin, used to pivot the crane, failing. Big Blue began tipping over toward the home plate section of the ballpark, bringing with it the 450-ton roof section it was lifting—right in the direction of a smaller crane holding a basket of three ironworkers. One of them quickly grabbed his walkie-talkie and repeatedly yelled out to anyone listening, “Get me out of here!” But there was no chance to save them in a split second.

The basket carrying the three souls plunged 200 feet to the crowd, killing them instantly. Five others were injured, including the crane operator—who decided it was safer to jump 20 feet than to hang around in the cab. (He suffered a broken hip and shoulder.) Curiously, someone entered the Mitsubishi trailer after the incident and disconnected a computer containing onsite weather information, thus erasing all wind data. While that may have hid the evidence, it didn’t do Mitsubishi any good in court; it was sued by the widows of the three men for negligence and, in December 2000, was ordered to pay a whopping $99 million in damages.

Structurally, the first-base side of Miller Park became a mess, with twisted metal everywhere. The stationary roof panel under construction and the steel frame that would provide window space below the arch all collapsed onto the bowl below, which sustained moderate damage. Fortunately, the ballpark board was fully insured for the $100 million in damages; the board had earlier been criticized for agreeing to a “Cadillac” policy totaling $492,000 in premiums, but no one was complaining now. Still, Big Blue’s fall set back Miller Park’s opening by a full year, burdening the Brewers back at County Stadium for one more season of financial red ink after having lost $46 million over the previous five years.

American Family Field’s formal entry façade is reminiscent of Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field—and cries for an equally graceful rotunda on the inside. Alas, there is none. (iStock)

Out of the Fonzie Era.

“The Egyptians designed their monuments to keep kings alive forever,” wrote Dale Hoffman of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “Miller Park is intended to get the Brewers to the World Series, a longer shot taken at greater political expense.”

For the moment, the Brewers were just content to step into their new ballpark and leave the World Series for another time. In the Spring of 2001, four and a half years after the first shovel was plunged into the ground, Miller Park was finally about to be become reality. A smaller replacement for Big Blue was brought in and managed to put up the remaining roof panels without incident, and the political ugliness that preceded construction was fading into a scarred memory. The cost of the ballpark had risen to nearly $320 million, not including another $75 million spent on surrounding infrastructure that wasn’t attributable to the increased sales tax.

Other numbers—the good kind—were also rising. Season tickets for the Brewers’ inaugural season at the new yard were up 50% to 14,000; the number of advanced tickets sold before Opening Day reached 1.8 million—a higher figure than the entire attendance during the Brewers’ last year at County Stadium. And though the average ticket price jumped from $12 per seat at County to $18 at Miller, it was still below the major league average of $19.

There would be several dress rehearsals. A three-day open house two weeks before the regular season home opener drew 137,000 fans, a much higher total than expected. Two exhibition games a week later all but sold out and provided dry-run information for the Brewers to iron out any wrinkles, from traffic patterns to concessions issues.

Fans and players alike were ecstatic about the new plant. “The easiest way to describe (Miller Park),” said Brewers outfielder Geoff Jenkins, “is when you walked down into County Stadium, it was like walking into a dungeon. It was just smelly and dark. This will be like going from a mine to the penthouse.” A Brewers fan put it more succinctly: “We’re coming out of the Fonzie era,” she told the Journal Sentinel.

The weather on April 6, 2001 for Opening Day was miserable: A chilly 43 degrees under overcast skies. But thanks to the closed retractable roof and a heating system that kept the temperature some 20-30 degrees warmer on the inside, nobody in the SRO crowd of 42,024 cared. Bud Selig rightfully threw out the ceremonial first pitch, but he was flanked by a star roster of politicians headlined by President George W. Bush, the former Texas Rangers owner who threw out a second ceremonial toss. Sean Casey of the visiting Cincinnati Reds—who hit the last home run at County Stadium and had already supplied the first hit at the year’s other new ballyard, Pittsburgh’s PNC Park—was the first to notch at Miller Park with a leadoff single in the second inning. A tight game followed into the eighth when Brewers slugger Richie Sexson delivered the decisive blow in a 5-4 victory with a one-out solo home run. When the game ended, the Brewers opened the roof so the fans could see it in action; it revealed a steady rain that had been falling outside. Fans got wet, but they didn’t mind.

Get into the Gap.

Sexson’s blast was one of 28 he would hit at Miller Park in its initial year, despite batting a blasé .266; both figures would come to epitomize the ballpark’s statistical personality. With consultation from two former Brewers—Hall of Famer Robin Yount and third baseman/general manager Sal Bando—American Family Field’s dimensions lead many to believe that the ballpark is a hitter’s haven, but that’s only partially true. The field plays relatively long down the lines—342 feet to left, 345 to right—but it’s cozy in the gaps, with distances just over 370. This rewards sluggers with gap power, while pull hitters have it a bit tougher.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t hard for people to tag the ‘bandbox’ label on Miller Park early on. Sexson’s 28 homers in 2001 is a ballpark record which still stands. Geoff Jenkins gave the venue its first three-homer performance in just its 14th game; four games later, Jeromy Burnitz gave it its second. In 2002, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Shawn Green delivered the ballpark’s most impressive display yet with he collected four home runs (along with a double and single) in a 16-3 thumping of the Brewers; the Dodgers added four other home runs to total eight on the night, another current facility mark. As with most ballparks in their early years, the pitchers eventually caught up to the hitters and figured out how best to pitch to the dimensions.

For potential batting champions, American Family Field might prove more difficult than they would initially perceive, as the shortened gaps allow outfielders to display more range relative to the territory they patrol. Over the first 20 years of the ballpark’s existence, the overall batting average was a less-than-magnetic .253, five points below the major league average during the same period.

One of the unintended consequences of American Family Field’s retractable roof—and the window spacing below its arched contours—is a pattern of shadows that wreaks havoc with players, especially as the afternoon progresses. (Flickr-dj0ser)

Roof Goofs and Other Oops.

There were some growing pains during Miller Park’s first year. The Brewers moved 400 season ticket holders to better seats after they complained of obstructed views. The entire infield, which had quickly grown rough, had to be torn out and replaced in May after a late winter didn’t allow it to settle in. A June night game was suspended after just an inning when a faulty sheet metal duct inside the ballpark created a partial power failure, making playing conditions unsafe; a 10-foot replacement duct had to be flown in and quickly installed the next day to prevent a second game from being postponed. And under the category of “gee, we didn’t think about that,” the retractable roof and the glass panes filling in space under the roof’s stationary panel arcs created sunlight issues during day games for the players with an unusual late-afternoon shadow pattern that, well, they would just have to get used to.

The roof was not without problems of its own, part of a disturbing trend over the facility’s early years. It suffered from leaks from the get-go, and gradually grew noisier with more vibration when in movement. A couple spritzes of WD-40 wasn’t going to solve the problem; the ballpark board discovered that the pivot bearings—which helped move the roof—had to be replaced. Astonishingly, there was no guidance, written or otherwise, on how to do it. A consortium of steel, machinery and engineering consultants grouped together to basically ad-lib a methodology, working through a typically harsh Wisconsin winter to get everything back on line, smoothly and quietly, in time for the 2003 season.

The ongoing roof issues became too much for the ballpark board, which sued Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of America—already in the hole $99 million for losing in court to the three Big Blue widows—for $49 million, claiming mismanagement and negligence. Mitsubishi countersued, saying it wasn’t paid $37 million in overbudgeted fees due to author changes from the board. The two sides came to an agreement days before court went into session; the board got $33 million, Mitsubishi $22 million. Insurance paid for it all.

The retractable roof isn’t the only thing that opens and closes at American Family Field. Here behind the center-field gate, an open space into the ballpark can be closed up with sliding translucent panels—one of which can be seen at far right. (Courtesy Frederick J. Nachman)

Letting in the Summer Breeze.

For all its early drama, American Family Field’s roof is still a marvel to behold for Brewers fans. Weighing an oppressive 12,139 tons—almost as much as the entire structure below it—the roof takes 10 minutes to open and close; each of the five moving panels (two others are stationary) is powered by a pair of engines running at 60 horsepower, with no added cost to the ballpark’s energy bill.

The roof isn’t the only thing that opens and closes at American Family Field. Less known are two translucent sliding walls, measuring 140×70 feet each, that open to each side of the main center field scoreboard and allow southern breezes to filter through, keeping fans a little cooler on a rare hot summer day in Wisconsin. So rare, American Family Field doesn’t bother with turning on the air conditioner—because the ballpark doesn’t have one.

If you don’t want to deal with direct sunshine even on an average Wisconsin summer day (when temps reach the upper 70s), the best advice is to buy a ticket on American Family Field’s first-base side, where you’ll be largely protected by the roof panels—especially as the sun gradually moves behind them in the later stages of the afternoon. Fans sitting along the third-base side, on the other hand, will want to pack some sunscreen. Wherever you sit, just make sure that you get a seat with good sightlines. Andy Tarnoff of onmiwlaukee.com complained, “I can’t find a single place,…including the press box, where you can see the entire field of play.” Tarnoff also points out that American Family Field, unlike other new ballparks of the time, do not have all seats facing toward the infield.

There are some positives about American Family Field’s seating arrangements. While it consists of four levels between the foul poles—suggesting the potential for nose bleeds at the top—they’re all petite in terms of row depth, allowing fans to be closer to the action. Even the field level contains only 20 rows, in stark comparison to other recently built ballparks that go back as far as 40.

Adding extra convenience for out-of-town fans, the Brewers smartly set the first pitch for Saturday evening games at 6:00, allowing them to return to their distant homes at a reasonable hour. Polling shows that nearly 20% of all American Family Field attendees come from outside of the five area counties paying for the ballpark.

A panoramic view of American Family Field from the upper deck. Though all seats are placed as close as possible to the field, the tradeoff is that almost none of them have a 100% view of the playing field; here for instance, you can’t see the left-field corner. (Flickr—Bryce Edwards)

Atta Boy, Attanasio.

The Brewers drew a Milwaukee baseball-record 2.8 million fans in their inaugural 2001 season at Miller Park—but a new ballpark can only keep the gate high for so long. To sustain good attendance, you’ve got to win. That, the Brewers could not do. They finished 68-94 in their first year at Miller Park, then collapsed to a dreadful, franchise-worst 56-106 in 2002; attendance fell with it, down to 1.9 million. It dropped even further in 2003 to a facility-low 1.7 million. Through their first four years at Miller Park, not only did the Brewers finish well below .500, they couldn’t even snare a winning record at home.

To the rescue came Mark Attanasio, who in 2005 purchased the Brewers for $223 million from Wendy Selig-Prieb, daughter of Bud Selig and, for the past decade, the team’s formal boss. Almost immediately, the Brewers improved; by 2008, the club finally made its first postseason appearance in 26 years behind the power-hitting duo of Prince Fielder and Ryan Braun and a surging second half from king-size pitching ace CC Sabathia, making a cameo at Miller Park before moving on to free agency. The Brewers’ ride back toward the top refueled the fan base, which now had a reason to show up beyond gawking at the new ballpark; for the first time, Miller Park drew over three million fans. The team has since remained competitive enough—not always contending, but at least providing colorful entertainment while trying—to raise the attendance floor above 2.5 million, occasionally topping out at three million. Again, it needs to be noted: This is baseball’s smallest market.

Brewers fans will even show up when their team isn’t playing. On numerous occasions, American Family Field has been used by other major league teams whose home parks were made unavailable by bad weather. In 2007, the Cleveland Indians had to rebook their entire opening home series in Milwaukee after heavy snow made it impossible to play at Progressive Field. (Some pointed out that it wasn’t the first time that Milwaukee stood in for Cleveland; for the 1989 film Major League, County Stadium played the role of Cleveland Stadium.) A year later, it was Hurricane Ike that sent the Houston Astros to Miller Park to play a scheduled home series against the Chicago Cubs and Carlos Zambrano—who threw the ballpark’s first no-hitter. And in 2017, the Miami Marlins moved its scheduled home series against the Brewers to Milwaukee after another destructive hurricane (Irma) caused minor damage to Marlins Park. The Brewers tried to make the Marlins feel at home for the three-game series, planting fake palm trees and pink flamingoes around the ballpark.

While there’s likely to be debate over what’s the most famous game at American Family Field, the majority can agree on the most infamous game—one which also didn’t feature the Brewers. In the ballpark’s second season, the 2002 All-Star Game was exciting for the first 11 innings; but there wouldn’t be a 12th or beyond, because both teams had run out of available pitchers—and coaches and execs were worried that the two left on the mound, Seattle’s Freddy Garcia and Philadelphia’s Vicente Padilla, would risk overuse if the game continued well into extra innings. After consultation, Bud Selig—now with the interim tag off his commissionership—gave a cutthroat gesture from the front row to tell everyone the game would end as a 7-7 tie. A sellout crowd hoping for a winner loudly booed their displeasure, and Selig took a lot of national—and local—heat for his decision.

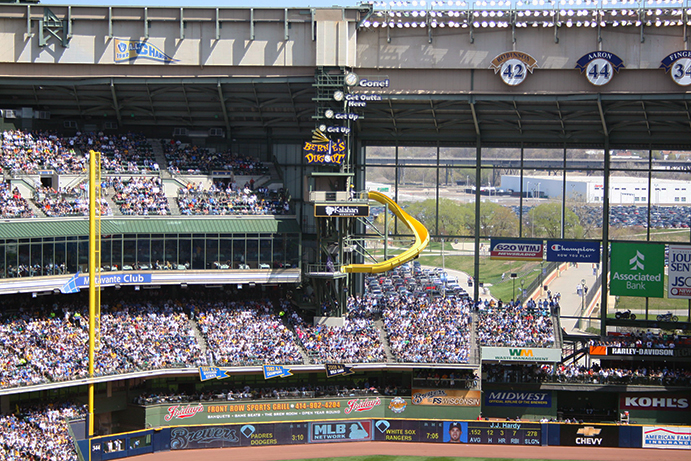

There’s much to unpack in this shot of American Family Field’s left-field corner. Included is Bernie’s Dugout, complete with slide; the sit-down restaurant (currently named the Restaurant to be Named Later) just above the outfield wall; and the more upscale, semi-private bar/buffet above the second (loge) level. Finally, note how the left-field foul pole intersects through the front of the loge level. (Flickr—Jaramey Jannene)

Bernie and the Brat Pack.

Besides the Brewers, American Family Field carries on with traditions that link back to County Stadium.

High above the left-field bleachers is Bernie’s Dugout, an erector set-mass of steel that houses the foam-padded Bernie outfitted with an exaggerated golden handlebar mustache and Brewers jersey. Every time a Brewer hits a home run—which happens often at American Family Field—Bernie takes a ride 30 feet down a curving yellow slide that looks borrowed from a public kids’ playground. The slide is flattened toward the bottom and, because of that, Bernie at first kept coming to a stop before the end; the Brewers took care of that by having him sit on something more slick to speed him up. Steeper than the slide is the minimum $175 one pays to partake in the “Bernie Experience,” which includes a ballpark tour, photos with Bernie (if he’s not elsewhere pounding down a pint) and, of course, a ride down the slide.

The more marquee between-innings attraction comes in the middle of the sixth inning with the famous sausage races. Five tall, foam-padded characters—Brat, Hot Dog, Italian Sausage, Polish Sausage and Chorizo—race along the foul territory warning track from pole to pole to find out who’s the fastest on the day. It’s a routine that’s become mimicked at other ballparks using different themes; at Washington’s Nationals Park, for instance, they use caricatures of former U.S. Presidents.

The sausage races haven’t been without bizarre controversy. As the sausages raced past the visiting dugout during a 2003 game, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Randall Simon thought it would be funny to take a bat and tap at the head of the Italian Sausage, otherwise known as Guido. The impact caused the young woman inside the top-heavy costume to fall forward, tripping up Hotdog; both fell to the ground, suffering scrapes to their knees. Simon was charged after the game by Milwaukee police with disorderly conduct and fined $432, and was tagged an additional $2,000 with a three-game suspension from Major League Baseball.

Ten years later, Poor Guido suffered more trauma when it suddenly went missing; an all-points bulletin went out, and soon after Guido was dumped in front of a bar north of Milwaukee by a couple of dudes who told the owner: “You did not see anything.”

The other tradition brought over from County Stadium is, of course, the pregame tailgating. And while that remains the choice of dining for many Brewers fans, there are other options to choose from, both inside and outside of American Family Field. In the east parking lot across State Highway 341, there’s the Tailgate Haus, an airy joint for private parties featuring catered buffets. Inside the ballpark, there’s a similar private area behind the right-field cyclone fence. More formally, there’s a sit-down restaurant right above the left-field wall that’s open year-round, serving classic Wisconsin-style grub; originally a TGIF Friday’s, it changed its name in 2020 to—wait for it—the Restaurant to be Named Later. Above, there’s a fancier eating spot that’s been named later three times; it’s currently branded as the Johnson Controls Stadium Club, available only to season ticket holders or those using one of the ballpark’s 70 suites. Reservations are strongly recommended.

Baseball’s two largest support posts, behind home plate, brace the base of American Family Field’s retractable roof. Those unfortunate to sit behind them are at least afforded with the ballpark’s cheapest ticket prices. Keeping those fans company behind them is a full-color sculpture of Brewers broadcaster Bob Uecker sitting in one of those nose-bleed “Uecker Seats.” (Wikimedia—Mshake3)

Have a Laugh, and a Cry.

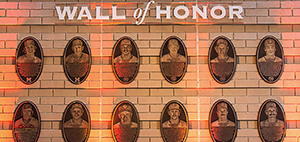

Like most current major league ballparks, American Family Field is surrounded by statues and tributes. On the outer ballpark wall near the third base-side entrance, there’s the Wall of Honor featuring plaques of famed Brewers players, coaches and execs. Near the main front gate is the Walk of Fame, with home plate-shaped tributes embedded into the brick flooring of Milwaukee baseball greats including those of the 1953-65 Braves. Dotting the same area are statues of Bud Selig, Robin Yount, former Braves/Brewers icon Hank Aaron and Milwaukee favorite Bob Uecker, short-time Braves catcher and long-time Brewers broadcaster.

Uecker’s mastery of self-deprecating humor earned him a second statue, of sorts, in 2014: A full-color, life-sized representation of Uecker sitting in a seat atop the upper deck, behind two gigantic beams—perhaps baseball’s largest support posts—in a comic ode to his famous Miller Lite beer commercial of the 1970s where he gets banished to the cheap, nose-bleed seats. “Fifty thousand empty seats,” Uecker crowed during the unveiling of the display. “What a ceremony!”

Besides the ballgame itself, perhaps the most entertaining attraction inside American Family Field is the Selig Experience, which opened in 2015. A tribute to the man who, more than anyone else, has kept baseball alive in Milwaukee, the exhibit features a museum area with artifacts, photos and cool facts, a recreation of Selig’s office at County Stadium, and a multi-media, triptych video presentation.

American Family Field’s most sobering tribute is located near the main home plate gate, with a sculpture of three construction workers called “Teamwork” which serves as a tribute to the three ironworkers who died in the Big Blue crane collapse. It’s flanked by a semi-circular wall that includes a plaque with the names of the three workers, the ballpark’s project leaders and all the participating entities who helped make American Family Field a reality.

A private buffet/bar area extends into American Family Field’s right-field space, adding a touch of porch to give hitters a better chance of collecting a home run—and a better chance for one of the patio’s patrons to collect the ball. (Flickr—Cragin Spring)

Happily Staying Put.

Two milestone moments regarding the Brewers’ ballpark occurred in the pandemic-torn year of 2020. The 1/10th-cent sales tax that funded the venue expired, some five years later than originally anticipated. And the Brewers made a deal with Madison, Wisconsin-based American Family Insurance to replace Miller Beer as the sponsored name of the ballpark through 2035.

The Brewers’ lease with the retitled American Family Field runs through 2030, but it’s hard to believe that the team will split for something better beyond that. That’s because it’s hard to imagine anything better. There was more pain and anguish to go around in the approval and building of the ballpark than any other in recent major league history, but Miller Park/American Family Field has not only proved that this great game can flourish in a small market, but that the Brewers are definitely in Milwaukee to stay.

For the pregame tailgaters, that’s certainly something to raise a beer and a brat to.

The Ballparks: County Stadium It was a plain stadium with a plain name, but the folks who paid for County Stadium provided the personality with brats, brew and a healthy dose of Gemuetlichkeit, bringing true Happy Days to Milwaukee by shattering 50 years of major league entrenchment and sparking a volatile period of geographical readjustment within the game.

The Ballparks: County Stadium It was a plain stadium with a plain name, but the folks who paid for County Stadium provided the personality with brats, brew and a healthy dose of Gemuetlichkeit, bringing true Happy Days to Milwaukee by shattering 50 years of major league entrenchment and sparking a volatile period of geographical readjustment within the game.

Milwaukee Brewers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Brewers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.