The Ballparks

Arlington Stadium

Arlington, Texas

Some like it hot. But most don’t. And that’s why it took a long time for major league baseball to arrive in the summertime oven known as the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.

Baseball’s lords had long known about DFW’s tempestuous weather. Meteorologically, there’s seldom a dull—or pleasant—moment to experience in this part of North-central Texas. Cold winter winds that sometimes beeline unabated from Canada can inflict major chill. The spring brings turbulent thunderstorms that on occasion rattle even long-time residents. Then there’s the summer, with its sweltering heat that raises temperatures to 100 degrees with humidity to sometimes match.

Until the art of nighttime baseball was perfected, baseball in the Dallas-Fort Worth region was a non-starter for major league think tanks. But even once the lights took hold and this great game could be played after the setting sun, doubt was still cast on the Metroplex’s ability to support big league ball.

Ultimately, neither Dallas nor Fort Worth would take the lead to convince that baseball could make it in the region. It would take a young, determined politician in a modest prairie outpost between the two cities to put the wheels in motion, create the facility to be known as Arlington Stadium, and turn his community into the unlikeliest major league sports town since Green Bay.

Anaheim by the Prairie.

In 1950, Arlington was but one of a few towns sprouting amid the gently rolling farmlands full of tall grasses and oak trees between Dallas and Fort Worth. It was home to barely 7,000 people, but growth was inevitable as Americans began the postwar migration from the saturated Northeast. To spur the momentum locally, Texas built the Dallas-Fort Worth turnpike, a six-lane tollway that would be completed in 1957 and run right through Arlington.

But Tom Vandergriff wanted to achieve something more than drive-by status for Arlington. Born in nearby Carrollton to the son of a successful local auto dealer, Vandergriff had quite the ambition to transcend Arlington’s simple suburban standing with unlimited vision. As a student at the University of Southern California, Vandergriff majored in broadcast journalism, but he also gained added education by seeing how nearby Anaheim, an outlying bedroom community not unlike Arlington, had become a focal point for tourists with the building of Disneyland. Returning to Arlington, Vandergriff jumped into politics, first as the head of the town’s Chamber of Commerce and, then at age 24, its mayor—a position he would hold for the next 26 years.

Once referred to by the New York Times as a man “who could make a living selling beer to the Women’s Christian Temperance Union,” Vandergriff channeled Anaheim by forging the creation of Six Flags, which opened in 1961 as a Disneyland-style theme park planted right along the turnpike. But Vandergriff didn’t stop there; he consistently sought other forms of family entertainment to rival Anaheim and later Orlando. He even lobbied Walt Disney himself to build a second Disneyland in Arlington, but Disney declined; too hot, he must have thought.

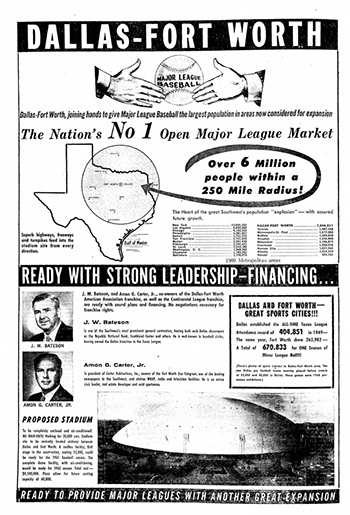

Investors hoping to lure an expansion franchise to Arlington developed this 1961 ad promoting the untapped Dallas-Fort Worth region and a domed ballpark. Surprisingly, baseball passed.

With the help of the Texas State Legislature, the Bi-County Sports Commission was created in 1958 with the sole purpose of exploring the possibility of a major league ballpark located somewhere within the participating counties of Dallas and Tarrant (home of Fort Worth). It seemed no surprise when Vandergriff took control of the commission and became chief lobbyist to place the proposed ballpark in Arlington, a convenient compromise providing an equidistant reach for spectators from Dallas and Fort Worth. A $12,000 feasibility study was commissioned to determine if the effort would be worth it; when it came back with a thumb’s up a year later, the commission took the matter to a public vote—where 75% of voters from both counties agreed in October 1959.

The proposed $9.5 million ballpark that Fort Worth architect Preston M. Geren Architects & Engineers had in mind was far more ambitious than anything Arlington Stadium would end up eventually becoming. It called for an initial open-air venue holding 35,000 seats with a domed roof, air conditioning and “invisible” lighting to be added a year later; further expansion plans called for an increase to over 60,000 seats with the addition of a second deck. All they had to do was raise the roof, however that would have been managed.

But no one was going to build anything in Arlington or anywhere until an actual major league franchise could be secured for the Metroplex. That process proved frustrating. The Continental League bowed once the two established leagues promised expansion. And when the leagues finally got around to it, Dallas-Fort Worth—considered a front-runner—lost in an upset as the majors focused on granting two cities (New York and Washington) with new teams as a mea culpa for the recent loss of the Giants, Dodgers and Senators; another was given to Los Angeles, which was hardly lobbying for one, having already snagged the Dodgers; and adding insult to injury, the majors added Houston, the Metroplex’s intrastate rival.

The Turnpike Years.

Having lost out on the expansion cycle, DFW’s next best hope was to convince an existing team to pack its bags for Texas. Despite some rumors of teams possibly on the move, including the Cincinnati Reds and Kansas City A’s—heck, the A’s under volatile owner Charles Finley were rumored to be headed everywhere—the door for franchise relocation appeared to shut after an active decade of movement.

So Mayor Vandergriff said the heck with it, let’s just build the darn thing anyway. Tarrant County voters agreed; in April 1964, 69% of them approved a bond measure that would give the okay to build a new convention center in Fort Worth—and a new ballpark in Arlington.

The initial venue would be far from the lofty descriptions first set out to attract major league expansion a few years earlier. It would seat only 10,600, and there would be no dome—in fact, there wouldn’t even be a grandstand roof to protect fans from either the hideous summer sun or the drenching rains of a sudden thunderstorm. The press box was pint-sized; there were no bleachers, just a tall, advertisement-choked outfield wall backed from behind by unending open space dominated by oak trees.

It was hard to see Turnpike Stadium, as it was originally named, from the turnpike it was named after. That’s because instead of rising from the ground, the ballpark was dug out of a hole 40 feet deep with seats placed on surrounding embankments; arriving fans entered at the top and walked their way down to the seats, which stretched from first to third. Overflow crowds would use the earthen banks down the lines if need be.

Perhaps the oddest look to be seen within Turnpike Stadium was the subtle separation of seating tiers. The lower half of seats touched the top half near the ends, but gradually arced downward toward home plate, like many of the swiveled sections seen at multi-purpose stadiums of the time. But these would not be moveable stands, and a section of premium seats would be wedged in between the two sides, backed by a tall retaining concrete wall below the upper tier. It’s a unique feature that would largely stick through the ballpark’s 29-year existence.

Most importantly, Turnpike Stadium was designed to be expanded if and when the time came for a major league team to finally arrive on the scene. But in the meantime, it would have to do as home for the Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs of the Class-AA Texas League, which provided for some interesting times. There was, during the ballpark’s inaugural season, the 25-inning game between the Spurs and the visiting Austin Braves, with future major league reliever Chuck Hartenstein pitching 18 frames for the Spurs. There was Paul Doyle, who threw the ballpark’s first no-hitter for the Spurs in 1968. And there was the first major league team to visit Turnpike Stadium, the Houston Astros, for an exhibition against a team of Texas League All-Stars; not feeling the goodwill of the occasion was veteran Astros slugger Jim Gentile, who was anything but when a bad strike call rubbed him the wrong way. It took numerous teammates to keep him from attacking the umpire.

Another umpire, Nick Emerterio, was not as fortunate. During a 1970 game at Turnpike, Spurs pitcher Greg Arnold took offense to a Emerterio balk call—then administered major physical offense upon Emerterio, beating him senseless and sending him to the hospital. Arnold profusely apologized for his sins after the game, but it wasn’t enough to keep him from being suspended for the final three months of the season.

Arlington Stadium, with the Dallas-Fort Worth Turnpike and Six Flags amusement park gracing the background. Note the dominance of the bleachers within the ballpark structure, and the ‘Lone Star’ scoreboard behind left field.

Get Shorty.

Talk of major league expansion heated up once more in the late 1960s, and the Dallas-Fort Worth market was again framed as a frontrunner. But while outsiders ridiculed suburban Arlington as “Hyphenville” and slammed baseball’s major league potential in a region dominated by its two favorite sports—football and spring football—Mayor Vandergriff faced more unexpected resistance from some powerful Texas natives: Roy Hofheinz, the Astros owner who feared the loss of up to $1 million in DFW broadcast revenue if big league baseball came to the Metroplex, and President Lyndon Johnson, recruited by Hofheinz to discourage Vandergriff and lobby against a second major league team in the Lone Star State. But Vandergriff persisted, tirelessly trying to sell Arlington to anyone willing to listen within the major league circuit while becoming a consistent presence campaigning his cause in The Sporting News’ “Letters to the Editor” column.

Hofheinz’s stiff-arm was enough to keep Dallas-Fort Worth from acquiring an expansion team for 1969, and Vandergriff and the voters of Arlington responded by doubling down. In May 1970, they overwhelmingly approved $10 million more in bonds not only to expand Turnpike Stadium to 20,000, but to also purchase 132 acres surrounding the ballpark, some of it for future parking. The reasons behind the move were twofold: One, to help encourage more fans to show up, whether it be for major or minor league ball, on top of the healthy attendance that the Spurs were already drawing; and two, to further gain the attention of a dissatisfied major league owner looking to move his team out of town.

In 1971, Vandergriff finally found one.

The Washington Senators, one of the expansion franchises that beat out DFW in 1961, had spent much of their first decade playing lousy baseball in front of small crowds—even after modern RFK Stadium had opened. Bob Short bought the Senators in 1968 and almost immediately caused chaos, undoing an evolving roster and fighting the owners of RFK over lease details. It was obvious that he wanted out of Washington. When Vandergriff offered up Turnpike Stadium to Short and his Senators to play a few exhibition games on short notice in 1969, it had to be assumed that at some point the opportunistic mayor sidled up to Short and asked, “So, are you happy in D.C.?”

Over the next two years, the potential move of the Senators to Texas gradually became baseball’s worst kept secret. When Vandergriff visited Washington for resettlement talks with Short, one cabbie—a Senators fan, obviously—figured out who he was and threw him out of the taxi. Once he managed to make it to Short’s office, Vandergriff had to hide in a closet when David Eisenhower paid a surprise visit to persuade Short to stay in Washington on behalf of his father-in-law, President Richard Nixon.

After the 1971 season, Short made it official: The Senators would be Arlington’s, to be rebranded as the Texas Rangers. Turnpike Stadium would be renamed Arlington Stadium—the common sentiment preferred Vandergriff Stadium, but the mayor declined—and capacity was hastily increased to over 35,000. But all of the new seats would be bleachers, some 40 rows of steep aluminum benches with backs that curved from pole to pole and beyond by a few sections on each side. These new seats came off as so voluminous compared to the existing, more laid-back seating structures along the lines, people seated behind home plate must have thought they were looking out across a race track to something on the order of the Daytona International Speedway. Keeping in line with the rest of the ballpark, the bleacher seats would also be uncovered.

Atop the left-field bleachers would be a 200-foot wide, 40-foot tall scoreboard; protruding from its right side would be a unique 60-by-60-foot board carved in the shape of the state of Texas. Electronically contained within this board would be the count, outs, lineups and even umpires (by uniform number). The Lone Star tribute would essentially be the first bit of kitsch introduced to the ballpark.

Mulligan, Anyone?

The Rangers’ first year at Arlington Stadium was not exactly ideal. The players’ union picked a fine time to strike, as the scheduled home opener was delayed 15 days from a spring training work stoppage that overlapped into the start of the regular season. That likely muted enthusiasm and kept the Opening Night crowd down to 20,105—and much of those fans showed up late when excess turnpike traffic clogged the tollbooths.

Frank Howard hit the first major league homer at Arlington Stadium to help Texas defeat the California Angels, 7-6, but the season to follow would be one full of frustration for the king-sized slugger who averaged nearly 40 homers in each of his previous five years at Washington, and only nine for Texas in 1972. His plight was something of a microcosm for the Rangers’ offensive ineptitude in general. Arlington Stadium was partly to blame; although the ballpark’s symmetrical dimensions of 330 feet down the line, 380 to the gaps and 400 to dead center seemed reasonably acceptable to hitters on paper, they seemed further to reach thanks to persistent summertime winds from the Gulf of Mexico that blew in from right-center field.

There was also the fact that the Rangers, like the Senators before them, were just plain awful. The team hit just .218 with a skimpy 33 home runs in 77 games at Arlington in 1972, resulting in an abysmal slugging percentage of .297—or nearly 50 points lower than the career batting average of Ted Williams, who tolerated the whole year managing this mess of a team that finished with a 54-100 record, still the worst in franchise history.

Once the fans sensed a big-time loser on their hands, they stayed home; the Opening Day crowd was exceeded only once the rest of the year, and the Rangers barely averaged over 4,000 for 16 September home games, with the largest roars reserved when the public address announcer gave out the football score of the almighty Dallas Cowboys. The overall 1972 gate of 660,000 was nearly half of what Mayor Vandergriff anticipated, and short of Bob Short’s more reasonable goal of an even million. The American League, which initially had mandated that the Rangers further expand Arlington Stadium to 45,000 in 1973, saw the lagging attendance numbers and said, “Never mind.”

The Fleeting Stardom of David Clyde.

While capacity stayed the same for 1973, there was expansion of spectator access, restrooms and concession stands at Arlington. The additions came in handy only when one guy took the field: David Clyde. Barely graduated from high school in Houston, the right-handed pitcher was billed as the next Sandy Koufax; the hype became palpable when Bob Short, in a desperate move to put much-needed butts in the Arlington Stadium seats, drafted Clyde, went against the advice of his scouts and had him bypass the minors to start immediately for the Rangers. It was a short-term success, long-term disaster; an overflow crowd of over 35,000—11,000 more than the ballpark’s previous top draw—showed up for the 18-year-old’s debut, which he won; another 33,000 was counted for his second start five days later, which he almost won. (The Texas bullpen blew a slim lead.)

For the next eight weeks, a David Clyde start became an event, with crowds continuing to soar past 20,000 when the Rangers were otherwise lucky to being in 10,000. But Clyde gradually became more mortal—he was never that immortal to begin with—Short refused to send him to the minors, and the fans eventually lost interest. Once the football season began and the Rangers crawled toward the bottom of another 100-loss ledger, Clydemania petered out to the point that by late September, only 2,513 fans—the smallest crowd in Rangers history—showed up to watch him pitch on a rare Friday afternoon game as the Friday night lights of high school football beckoned. Clyde’s career basically peaked with his very first appearance; by the time he finished pitching his last game in 1979 at age 24, he had accumulated a career 18-33 record and 4.63 earned run average. Hardly the stuff of Koufax.

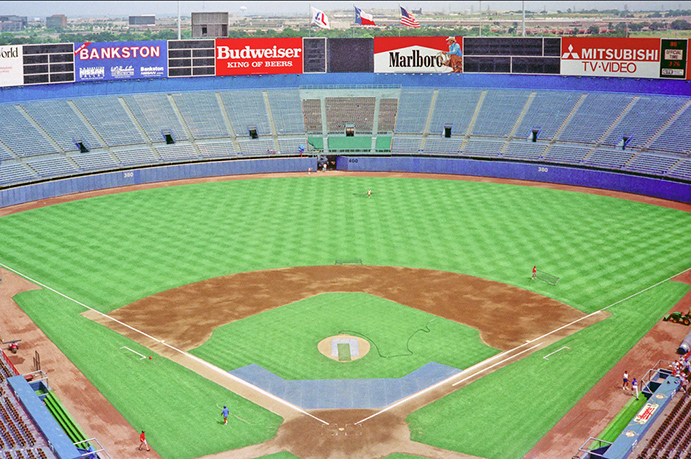

A view of the playing field and bleachers in the late 1980s. The recently added wall behind the bleachers, full of ads and various scoreboards, cut down on the winds blowing in from right-center field and gave power hitters a long-sought advantage. (Jerry Reuss)

After two rotten years to begin their Arlington Stadium existence, the Rangers in 1974 turned the page on numerous fronts. Bob Short sold, emitting sighs of relief from most everyone tiring of his penny-pinching rule. The team finally answered the cries of frustrated hitters by moving the fences in at the gaps by 10 feet. The cries of overheated players were answered by scheduling virtually every home game between June and August at night, and installing air conditioning in the Rangers dugout (but, curiously enough, not the visitors’). Jim Sundberg, the six-time Gold Glove catcher, fan favorite and unsung hero who logged more games (770) and hits (582) than anyone in Arlington Stadium history, made his major league debut and earned a spot on the AL All-Star team. And the team got a huge bump in the standings from last place to second thanks to first-year manager Billy Martin, who grew to embrace the area—perhaps because his good friend and drinking buddy Mickey Mantle lived nearby in Dallas. Like most everywhere else he managed, the caustic, turbulent Martin quickly wore out his welcome and was fired before he could complete a second full season in Texas, but at least he lifted the Rangers out of the laughingstock class and into a more respectable, if never triumphant, mode that would last through the remainder of their tenure at Arlington Stadium.

Martin’s brief time in Arlington presaged the nomadic comings and goings of star players who put on the Rangers uniform over the next 10 years. Ferguson Jenkins, Gaylord Perry, Bert Blyleven, Bobby Bonds, Sparky Lyle and Rusty Staub were among the more notable names who came, saw, and left before they could conquer. One who could claim triumph over the ballpark was borderline All-Star Al Oliver, who benefitted from a line-drive style of hitting which was never affected by the nonstop winds blowing in from right-center. Oliver wore the lowest uniform number in history (“0”) and produced the highest career batting average at Arlington Stadium, hitting .346 over four years of play for Texas.

The Rangers’ early years at Arlington Stadium were also remembered for the introduction of the nacho to the American ballpark. Invented in 1943 by Ignacio Anaya on the Texas-Mexico border near Eagle Pass, the nacho craze grew throughout the state and was sold for the first time at Arlington by Ignacio’s son, Tony. It was a big, messy, smelly hit; one was sold for every two fans at the ballpark, far above the ratio for other, more traditional ballpark standards such as hotdogs and popcorn. The few fans who didn’t buy were probably too busy plugging their noses.

Whether Arlington Stadium fans loved or hated the nachos was not the point; the Rangers were just happy to see more of them showing up at the ballpark, disproving the theory that major league baseball in the football-mad Metroplex wouldn’t work. The Rangers surpassed a million in attendance for the first time in 1974 and never sank below that figure again, the strike-shortened 1981 season excepted. Arlington Stadium became more accessible in the minds of many starting in 1978 when the Dallas-Fort Worth Turnpike deconstructed the booths and became toll-free. Thus, the Rangers and the City of Arlington spent some $4 million to increase capacity to 41,284 with the addition of an upper deck that stretched from first to third base. The move paid off; despite a seven-game drop-off in wins from the year before, the Rangers still managed to bring in 200,000 more fans to total nearly 1.5 million.

Arlington Stadium looking down the right-field line. The upper deck was added in 1978; to its right is a double-decked structure of luxury boxes, constructed in 1984. (Jerry Reuss)

Just Because it’s 1984 Doesn’t Mean You Have to Go Orwellian.

Arlington Stadium’s next, and final, major makeover took place before the 1984 season. The city pumped in $12 million to add 2,000 more seats, flank the upper deck with two levels of luxury boxes—because the glitterati of the Metroplex had to sit in some sort of air-conditioned comfort—and build a 30-foot barrier atop the back of the bleachers, making the ballpark’s rear even bigger than it already appeared. The wall featured five different scoreboards equally spaced out between gigantic billboards; there were two out-of-town boards in left field, a “Diamond Vision” video screen in center, the basic in-game information board in right-center and, at right, a smaller reading of the time and temperature—which fans avoided looking at on a hot night, lest they were rooting for the number to lower to a cooler reading.

The first season at yet-again updated Arlington Stadium did not go swell for the Rangers. They instituted an ill-advised policy of banning all outside food, and Opening Day fans didn’t get the memo—or they dared to be disobedient about it—as hordes of food were taken away at the gate under a strict enforcement of the new ban. Long lines ensued as fans missed what little action there was on the field—the Rangers lost to Cleveland, 9-1—and to add insult to injury, when the fans came back to get their food at the end of the game, they found the guards eating it. Trying to shed humor on the situation, a Rangers employee joked to the media: “We told (park employees) that the job didn’t pay much, but they get all the food they can eat.” Still, it was a PR nightmare the Rangers had to correct, and they eventually did—six weeks into the season.

The shame continued from there. An Arlington Stadium vendor was fired after he wrote to the area’s major newspapers complaining of lower commissions, causing another publicity headache. On the field, the Rangers suffered through a 69-92 record—their third of four straight losing seasons, their longest such dry spell in Arlington Stadium history—and the year came to a fitting end when, on fan appreciation day before 8,375, all 27 Rangers who came to bat were retired by the Angels’ Mike Witt in what would be the only perfect game thrown at the ballpark.

The erection of the tall retaining wall behind the bleachers not only cut down on the winds, but the breezes that passed over bounced off the upper deck seating and luxury box structures behind home plate and finally made Arlington Stadium advantageous to sluggers—even with the fences having been moved back to their original gap distance of 380 feet by 1982. Home run output more than doubled at the ballpark from 78 in 1983 (the last season before the retaining wall was built) to 178 two years later; two more years after that, in 1987, the trend peaked with a ballpark-record 204 long balls clearing the wall.

In 1987, the Rangers bought Arlington Stadium from the city—a move that seemed askew a year later when they sent out a press release saying they had sold the team to investors in St. Petersburg, Florida, who were intent on luring a major league team to the soon-to-be-built Suncoast Dome (Tropicana Field). Team owner Eddie Chiles then pulled back and decided to sell instead to local interests headed by future President George W. Bush. The incoming Bush regime made it clear that Arlington Stadium was not in its long-term plans; despite all of its upgrades, the ballpark was still seen by many as an overgrown minor league facility for which no tear would be shed if the Rangers bolted, whether it be Florida, Dallas or somewhere next door. The Sporting News’ Michael Knisley chided Arlington Stadium for having all “the charm of a chisel,” while Skip Bayless, the Dallas Times Herald columnist never known for subtleties, referred to the ballpark as “Arlington Cemetery.”

Shortly after Bush and Company took command of the Rangers, they worked with Arlington to propose a new ballpark that would be placed just southwest of Arlington Stadium. The voters, once again, got a say in the matter; and, once again, on January 19, 1991, they said yes to the Ballpark at Arlington, officially sealing Arlington Stadium’s fate.

When Texas native Nolan Ryan took the Arlington Stadium mound for the Rangers, big crowds were sure to follow. The Hall-of-Fame pitcher, at age 45, delivers here before a nearly packed house in 1992. (Flickr-Ryan)

A Glowing Sunset.

Ironically, Arlington Stadium’s lame duck years would produce much of its greatest glory. After years of ever-changing rosters, the Rangers developed mainstays on offense with Ruben Sierra, Julio Franco and Rafael Palmeiro; all three of them collected at least 200 hits in 1991. New faces arrived in superb catching prospect Ivan Rodriguez and power slugger Juan Gonzalez; another potential bopper, a skinny young kid named Sammy Sosa, got away in an ill-fated trade late to the Chicago White Sox in 1989.

But the man who made Arlington Stadium truly come alive in its final years was Nolan Ryan.

The hard-throwing strikeout machine, native Texan and free agent after nine years with the Houston Astros, Ryan made maintaining a Lone Star address a priority over money, and signed a nice (but not budget-busting) deal with the Rangers. Many believed that the 42-year-old Ryan had little gas left in an arm taxed with over 4,500 innings and wouldn’t be able to stand up to the Metroplex’s notorious summer heat, even at night. Instead, to the delight of the Rangers and their fans, Ryan was tanned, rested and refueled for a glowing career sunset.

In 1989, Ryan struck out 301 opponents—his first reach to 300 since his prodigious reign with the Angels a dozen years earlier; one of those Ks was an unprecedented 5,000th, striking out Oakland’s Rickey Henderson. In 1991, he threw a record-breaking seventh no-hitter against Toronto, mowing down 16—the most he ever struck out at Arlington Stadium. And in 1993, an increasingly brittle, 46-year-old Ryan, responding to one of his own players being earlier drilled by a pitch, delivered payback to the White Sox’ Robin Ventura—who dared to storm the mound and take on Ryan in front of 32,000 jaw-dropped Arlington spectators. Ryan met the challenge, putting Ventura into a headlock and punching him several times before the inevitable separation by teammates. Ventura was ejected and Ryan was not—providing proof that reputation does precede oneself. The Ryan-Ventura donnybrook is arguably considered Arlington Stadium’s most memorable moment.

Embraced as a native son, Ryan was wildly popular at Arlington. The Rangers drew 10,000 more fans on average when he took the mound at the ballpark; it doesn’t seem quite right that his career numbers at Arlington Stadium amounted to a modest 39-31 record and 3.64 ERA, but his 703 strikeouts are second in the ballpark’s history to long-time Rangers knuckleball artist Charlie Hough—who needed nearly twice the innings as Ryan to rack up his 771 Ks.

Ryan was on target to start Arlington Stadium’s final game on October 3, 1993—but those plans were ruined two weeks earlier in Seattle when he tore a ligament in his throwing arm, ending both his season and career. He had to settle for spectator duty as the Rangers bowed 4-1 to the Kansas City Royals and George Brett (playing the final game of his Hall-of-Fame career) before 41,039 fans.

In the end, Arlington Stadium’s 22 years as a major league facility proved to be nothing more than a prolonged placeholder for something better. It lacked both aesthetic and historical prestige. The ballpark hosted neither an All-Star Game nor a postseason game; no other major league venue lasted as long without either. Yes, you could do cool things at hot Arlington Stadium that you couldn’t do elsewhere, like fry and egg on a boiling aluminum bleacher seat or watch pitcher Danny Darwin collapse from the heat after a game—as he did in 1980 following a complete game effort. But for Rangers fans, it was their ballpark, and they did their best to hide whatever contempt they had for it—as evidenced by the two million-plus fans who packed the joint in each of its last five years, all while the Rangers teeter-tottered around the .500 mark. They were mild-mannered, good-natured fans who came to be entertained and to entertain, singing Cotton Eyed Joe for the seventh-inning stretch—because that’s the Texan thing to do.

As Arlington Stadium slowly became dismantled in the shadow of the newly opened Ballpark of Arlington in 1994, one would perhaps have sighed watching part of Tom Vandergriff’s legacy being disassembled. But Vandergriff’s legacy remained vibrant and could be seen all around. The little berg of Arlington he took the lead on has become a major destination, home to the Rangers, Dallas Cowboys (at the glitzy AT&T Stadium), water parks and, still after all these years, Six Flags—which has become a national theme park brand.

Arlington surely would have grown without Vandergriff, but it would have grown in anonymity like Grand Prairie, Richardson, Plano or many other DFW burbs. Shakespeare once wrote, “What’s in a name?” The answer, thanks to Arlington Stadium, is quite a lot for the House of Vandergriff.

The Ballparks: Globe Life Park When the Dallas-Fort Worth suburb of Arlington took in the Texas Rangers in 1972, it welcomed them to an overgrown minor league facility that did the team’s karma no good (read: no postseason) for 22 years. Then it built what’s now Globe Life Park, and the magic arrived in the form of four first-place finishes in its first six years. It’s certainly overtime fun for employees “working” in the business offices behind the center-field fence.

The Ballparks: Globe Life Park When the Dallas-Fort Worth suburb of Arlington took in the Texas Rangers in 1972, it welcomed them to an overgrown minor league facility that did the team’s karma no good (read: no postseason) for 22 years. Then it built what’s now Globe Life Park, and the magic arrived in the form of four first-place finishes in its first six years. It’s certainly overtime fun for employees “working” in the business offices behind the center-field fence.

The Ballparks: RFK Stadium Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

The Ballparks: RFK Stadium Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

Texas Rangers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Rangers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.