The Ballparks

Braves Field

Boston, Massachusetts

(Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

Sprawling in scope and vanilla in appearance, Braves Field never captured the imagination like nearby Fenway, becoming outdated shy of its prime after being hailed as the ultimate Deadball Era park—where deep flies were kept in but thick railroad smoke couldn’t be kept out. Once the home run became trendy, one clueless owner after another didn’t know what to do with the joint—and usually they did nothing.

Stroll westward today along Commonwealth Avenue away from Fenway Park, past the stately structures of Boston University and the slicing Massachusetts Turnpike, and you’ll find yourself upon a campus playground. Among this expanse of fun are a beautiful arena, a swimming hall, tennis courts and a recreational soccer pitch. But there’s also Nickerson Field, surrounded by hi-rise campus dorms, outlined with tartan track, filled inward by artificial turf and bordered on one side by a 10,000-seat pavilion.

Football was played at Nickerson Field. That was, before budget deficits and Title IX doomed the BU gridiron program in 1997. But well before that, baseball was king at the corner of Gaffney and Akimbo—or, as it goes by today, Harry Agganis and Braves Field Ways. Those who come to Nickerson to watch a graduation ceremony, or a game of lacrosse, or to just relax and take in the Boston sunshine, likely don’t realize that this very pavilion once sat spectators for three World Series, the dawn and sunset of Babe Ruth’s career and the longest major league game by innings.

The pavilion, and the stylish main entrance building behind it that now serves as the university police station, are all that remains of Braves Field, once upon a time an unprecedented plant of 45,000 seats with a vast playing field emblematic—and then some—of a Deadball Era in full laborious swing. When it debuted in 1915, Braves Field was praised by National League president John Tener as “the last word in baseball parks.” It would be the last NL park built, period, until Milwaukee opened County Stadium nearly 40 years later and lured the Braves away from Boston to play in it.

All We Need is a Miracle.

In baseball’s early days, Boston was the place to go—and that was before the Red Sox were born. The Red Stockings, as the Braves were first called, began play in 1871 and remain today as the oldest continuously running major league team. In the 19th Century, the Red Stockings—later called the Beaneaters— were the gold standard. They took first place 12 times before the Turn of the Century, built one of the game’s first elegant (albeit wooden) ballparks in the South End Grounds and were fervently followed by locals, most particularly by a rabid group of fans known as the Royal Rooters.

The advent of the American League turned Boston baseball on its head. Not only did player raids deplete the once sterling talent base of the Beaneaters, but the arrival of the Red Sox—and their early success—spelled further doom. There was crisis in the standings—11 straight losing seasons—crisis at the gates with deflated attendance and an identity crisis with the team changing names three times over a five-year period as various owners came and went. Even the Royal Rooters changed their allegiance to the Red Sox.

Worse, as baseball’s steel-and-concrete ballpark boom commenced, the South End Grounds became an embarrassing timbered relic, its meager 10,000-seat capacity rarely filled for a team playing a rotten brand of ball on the field.

To the rescue came a new group of owners in 1912 led by James Gaffney, a former policeman and construction magnate who ranked high within New York’s powerful Tammany Hall political machine. Along with retired Hall-of-Fame pitcher John Montgomery Ward (who later bowed out via irreconcilable differences), Gaffney quickly restored stability to the name by calling the team the Braves, and more slowly righted the franchise—but he was still stuck with a lousy ballpark. In order to boost his chances for a new one, Gaffney needed a miracle from his team; he got it in 1914 when the “Miracle” Braves went from dead last on the Fourth of July to the NL pennant through an unprecedented rampage of victory, capping the memorable ascent by sweeping the star-studded Philadelphia Athletics at the World Series.

The Braves’ furious rally quickly made them too big for the South End Grounds. In order to attract far bigger crowds they knew would show up, the Braves scheduled late-season games at neighboring, 35,000-seat Fenway Park, the young home for the Red Sox, and continued using it for the World Series. Gaffney seized upon the momentum and immediately drew up plans for his own ballpark, one that would outmuscle all others previously built.

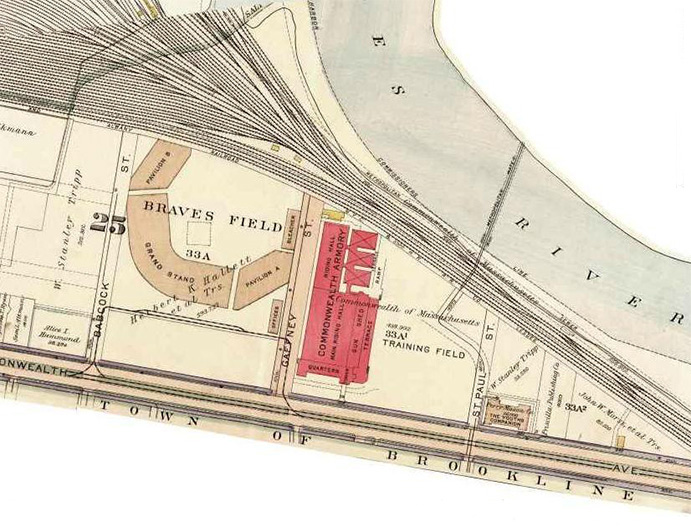

This schematic of Braves Field shows its close proximity to a major railroad yard (which contributed much cough-inducing pollutants over the ballpark) and the Charles River beyond. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

A Mountain of Concrete and Steel.

The steel-and-concrete ballpark era would be renowned for embracing the ornate and the intimate, but Braves Field would contain neither. It was an industrial-strength facility with the look of a common industrial plant. Gaffney was said to be intensely hands-on in the design process with Cleveland-based Osborn Engineering, but he didn’t appear to draw much influence from the game’s majestic palaces opened in recent years like Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field or Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. Braves Field would be less about grace and more about bulk—in The Sporting News’ words, “a veritable mountain of concrete (4,100 tons) and steel (750 tons).”

Taking up space where a golf course once stood, Braves Field originally was to hold 45,000 seats, with all but 2,000 of them situated from pole to pole and covered by an enormous grandstand roof. Budget realities reduced the capacity to 40,000, with the facility split into three main seating areas: A main grandstand seating 18,000 with the big roof retained, flanked by two detached, 10,000-seat pavilions that veered diagonally toward the outfield corners and practically faced one another. No one was going to acquire vertigo making the long trek from the first row to the last; Braves Field’s three main sections were laid-back and deep—nearly 60 rows deep—but not steep, with a pitch so gentle that someone once estimated the distance between the two seats furthest apart from one another, and came up with roughly 800 feet.

Beyond the banal ballpark structure, true architectural character could actually be found at Braves Field’s most peculiar spot, the three-story building perched behind the right-field pavilion that had the look of a relaxed, old-style Spanish railway station with its red, mission-like roof tiles and ground-level series of open-air arches. Serving as the Braves’ ticket booth, main entrance and (upstairs) team offices, the building and its location seemed inspired by Cleveland’s League Park, which funneled fans through a similar house-like structure near the right-field corner.

Gaffney was smart enough—and politically powerful enough, thanks to his Tammany Hall past—to convince Boston’s streetcar system to lay down a loop of track one block off Commonwealth Avenue and literally right through Braves Field, stopping behind the main grandstand to let fans out to walk up a main ramp to their seats. The loop remained in service through 1962, 10 years after the Braves left Boston. Little if any trace of it remains today.

Bleachers in left and center field filled in parts of what originally was one of baseball’s largest playing fields. The outfield dimensions were constantly tinkered with, as bleachers appeared (as seen here in the late 1930s) and then disappeared. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

When Fenway Park Played Second Fiddle.

Built in just five months, baseball’s first million-dollar ballpark opened on August 18, 1915 with an overflow crowd of 46,000; it was the largest such gathering for a baseball game to date in what would be the majors’ largest ballpark until Yankee Stadium dwarfed it in 1923. The Braves sent the patrons home happy as Dick Rudolph went the distance and outdueled the St. Louis Cardinals’ Slim Sallee for a 3-1 victory.

Braves Field gave its main tenant a boost—and nearly another miracle finish; the Braves won 31 of 47 games after their debut at the new ballpark before running out of time to catch the Philadelphia Phillies, who placed first by seven games. And in a bit of local irony, the Boston Red Sox—the Phillies’ World Series opponent—asked the Braves for permission to use Braves Field for the Fall Classic, a year after the Miracle Braves had taken over Fenway for the 1914 Series. Sure, Fenway Park was new and nice, but Braves Field sat 10,000 more fans. And more fans meant more revenue. And more wins: In using Braves Field for both the 1915 and 1916 World Series, the Red Sox were a perfect 5-0 at their home away from home—winning each game by a single run—to help grab consecutive world titles.

The highlight of the 1916 Series came in Game Two, a 14-inning affair between the Red Sox and the Brooklyn Robins—who had a thing for going extra frames at Braves Field, as you’ll later discover. The Red Sox triumphed, 2-1; going the full 14 innings for Boston was 21-year-old pitcher Babe Ruth, the future home run king who, on this day, became king of the hill by allowing just a run on six hits.

The Red Sox were so enamored by the seating capacity of the Braves’ new home that there was actual talk between the two teams, circa 1918, of sharing the facility on a full-time basis—with Fenway Park being demolished to make way for a parking lot. The conversation died and Fenway made it to 10 years of age—and later, 100.

Fans depart from Braves Field following a game in the 1930s. The building shown here functioned as the ballpark’s main entry and team offices, although it had no aesthetic relationship with the more mundane looking grandstand and pavilions. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

The Endless Outfield.

Those who came to Braves Field weren’t only wowed by the expanse of seats, but the expanse of the playing field. It was huge. James Gaffney was a fan of the Deadball Era and its predilection for the triple and inside-the-park home run. He despised cheap homers hit over a short wall and the lazy trot that followed; at South End Grounds he had moved the fences back, and now he laid out a ballpark where no one would be rewarded for a gimme four-bagger—or a well-earned one. The outfield wall was a long way from home; the distance to the foul poles was 400 feet, but that was nothing compared to the Herculean 550 it took to reach the deepest point of the park, to the right of center.

Ty Cobb once bragged before a game elsewhere that he would hit home runs just to prove he could do it (he wound up hitting three on the day), but he knew he’d be fool to make such a dare at Braves Field. Being an American Leaguer, Cobb never played at Braves Field, but found the time one day to saunter over from Fenway Park to check out Gaffney’s gargantuan greens; he was convinced no one would ever clear the distant, 10-foot concrete wall, praising the ability to “play an absolutely fair game of ball without the interference of fences.”

Cobb wasn’t exaggerating. It seemed futile to even try and go for the fences at Braves Field. In the first year-plus of action at Braves Field totaling over 100 games, only 13 home runs were hit—all of them inside the park. It wasn’t until 1917 when someone—the Cardinals’ Walton Cruise—became the first to finally send one over the relatively less distant right-field wall. Four years later, he became the second. It’s too bad warfare technology hadn’t advanced to the point that his groundbreaking shots could be nicknamed “Cruise Missiles.”

Over in left field, the wall remained unconquered; no one had even hit it on the fly until 1921. Finally, in 1925—10 full years after Braves Field had opened—the New York Giants’ Frank Snyder became the first to clear the wall in left.

While few baseballs cleared the wall, some managed to go through it. Bill Rariden and Johnny Rawlings belted now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t drives that bounced to the scoreboard on the left-center portion of the wall and went right through open slats that the operator hadn’t filled in. Both counted as home runs.

If Braves Field’s voluminous dimensions weren’t tough enough on the tape-measure artist, there was this: The wind typically blew straight in from center field. In one 1937 game, the gusts were so strong, an opposing hitter was said to belt a drive to center that was caught by the Braves—behind home plate.

The northerly winds also proved hazardous for those in the park who occasionally choked on the smoke blown in from old-fashioned locomotives, passing right behind the left-field wall on a series of railroad tracks that separated Braves Field from the Charles River. By the 1940s the Braves attempted to remedy the issue by planting fir trees behind the wall to absorb the soot, and when that didn’t work out the team asked the railroads to only run diesel engines past the ballpark during games.

The Bad News Braves.

James Gaffney didn’t wait long to get out. Just a year after opening Braves Field, he sold the team—but kept the ballpark, leasing it out to the Braves until 1949 when his heirs sold it back to the ballclub for roughly $750,000. But there had to be a few moments where Gaffney would shake his head and give advice to a procession of incompetent owners who followed on how to run a major league team—and the ballpark they played in. They certainly needed it.

As the Red Sox did a swan dive into the depth of the AL standings during the 1920s by essentially giving away all of their talent to the New York Yankees, the Braves failed to take advantage—in large part because they were just as bad and drew even less fans to Braves Field than did the Red Sox at an emptied out Fenway. At one Braves game, a sportswriter was able to quickly count to 12 the number of fans seated in the 2,000-seat bleachers behind right field and famously labeled the section the “Jury Box.” And when the day was done, chances were that the dozen fans gave a guilty verdict on the play of the Braves.

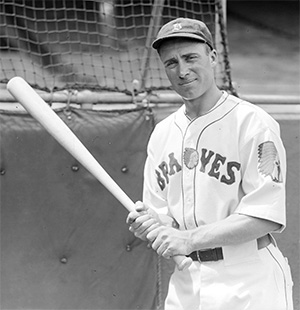

Without Wally Berger, who belted far more home runs (105) at Braves Field than anyone else, the Braves would have been much worse than they already were during the 1930s. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

Fuchs sold the team to Bob Quinn, because who else would be better suited to take the reins of a losing franchise than one with a resume of running the downtrodden St. Louis Browns and the wretched, post-Ruth Red Sox? Quinn quickly showed off his incompetent stripes when he somehow led the press to believe that the 1936 All-Star Game—generously gifted to Braves Field—had been sold out. The media reported that tickets were no longer available, and the NL went on to clinch its first-ever Midsummer Classic victory before 25,000 fans—and 20,000 empty seats.

Quinn was perceptive enough to shake up the brand, allowing fans to come up with a new team name. For whatever reason, they chose “Bees.” Braves Field was officially renamed National League Park, while unofficially the ballpark’s nickname changed from the Wigwam to the Bee Hive. It wasn’t the Place to Bee, as the Bees failed to generate any buzz and continued to languish at the bottom of the NL standings. “Bees” never really stuck and the team went back to “Braves” in 1941.

Throughout this dark period of musical-chairs ownership, Braves Field sat largely neglected, with seats that were never replaced, walls that were never repainted and enhancements that were never thought up. And if a ballpark needed constant freshening, it was this one, exposed to all the pollutants spewed out from the trains running behind the outfield wall.

Shifty Bleachers.

What little cash these owners did spend on Braves Field was allotted toward reshaping the playing field. When Ruth began smashing one majestic home run after another and the imitators ensued, ballparks all around the majors reduced their distant Deadball Era field dimensions to encourage more scoring, more home runs and more revenue from more fans. Braves Field, with its endless outfield expanse worthy of Nebraska, remained one of the last holdouts—not so much out of defiance but through management ambivalence. Finally, in 1928, the light switch went on in the Braves’ front offices and the team joined the live-ball crowd, building bleachers in front of the wall from left to center and placing a new fence in from of it. The new set-up reduced the original field dimensions anywhere from 60-to-80 feet, with the less voluminous right field remaining as is. But home runs started coming too easy; when the Braves’ Les Bell belted three into the new left-field bleachers and came awfully close to a fourth—all in one game—the Braves probably realized they had gone too far and moved the new fence back some 30 feet before the end of the season.

The tinkering would continue for the next two decades. In 1929, they moved some of the fences back in and seriously reduced the distance down the right-field line from 364 feet to a miniscule 298. In 1933, everything got moved back. In 1936, they rotated the field to the right to put more room back in left—and less in right. A year later, they sliced out a portion of the right-field pavilion and moved the foul pole 80 feet back to 376. In 1940, the whole field was reduced, again. And so on, and so on. The playing surface received more facelifts than a vanity-driven Hollywood starlet; one began to wonder if even the Braves knew what they were going to do with the fences, as the team continued to meddle with location even in the midst of the season. No matter how you sliced it—or rotated or shortened or lengthened it—Braves Field pretty much played as a pitcher’s park from its first day to last, frequently playing 10-25 batting points below the league norm.

Whether the fences were cozy or distant, the Braves could always count on Wally Berger to carry the offense. And no other player in major league history carried a team the way the right-handed slugger did when he accounted for nearly half of the team’s home runs over a seven-year period from 1930-36. Without Berger and the 105 home runs he belted at Braves Field—easily the most ever hit by anyone at the venue—an already bad Braves team would have resembled the 1962 New York Mets year in and year out.

Visiting teams loved Braves Field because they felt confident of leaving with a win, but the Brooklyn Robins/Dodgers really must have got a kick out of playing there—because once they got there, it seemed like a long time before they left. Brooklyn and the Braves went to extra innings 45 times at the ballpark, and some of those games went on forever. The most memorable of those marathons came in 1920 when the two teams battled for a major league-record 26 innings before giving up on a 1-1 tie; just two days later, they jousted for 19 more innings with the Braves earning a 2-1 decision. In 1939, Boston and Brooklyn nearly reset the record, but darkness cut a deadlock short at 23 innings. And a year later, the two teams battled for 20 more innings in a game taken by the Dodgers, 6-2.

Renovation Sensation.

In 1944, the franchise finally attracted ownership with a cause. A triumvirate of local construction bigwigs referred to as the Three Little Steam Shovels took over the team and set about giving Braves Field some long-overdue TLC. They added lights, put up a massive 68-foot tall scoreboard that prominently featured a 3-D Chesterfield cigarette ad reminiscent of the near-iconic scoreboard ad at New York’s Polo Grounds, and painted the foul poles in fluorescent colors so they could be seen better at night. Also painted, for the 1946 season opener, were some of the grandstand seats—but they didn’t dry fast enough for 330 fans who found their clothing stained by an unexpected coat of green; the Braves put an ad in the paper stating they would cover the dry cleaning bills of those affected and eventually doled out $6,000 to do so.

The monster scoreboard, one of many belated enhancements made to Braves Field in the late 1940s. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

Lou Perini, who ultimately would became the last of the Braves’ Little Steam Shovels and sole owner, publicly stated that he had visions of Braves Field “as I see it—in 1955.” He foresaw a ballpark expanded to 50,000, with the grandstand roof extended to cover both pavilions; a foot bridge over the railroads that would carry fans back and forth to a parking area alongside the proposed Massachusetts Turnpike; and a full-scale restaurant situated within the ballpark.

Not only did the fans respond to the new owners’ efforts to give Braves Field a sincere and aggressive makeover—attendance mushroomed in 1946 to nearly a million and, a year later, it topped the milestone—but so did the team itself. The Braves snapped a seven-year losing skid with an 81-72 mark in 1946, came within eight games of first place in 1947 and, in 1948, took their first NL pennant since the 1914 Miracle edition, attracting 1,455,439 fans in the process. The World Series that followed would be the only one the Braves would ever play at Braves Field; they lost in six games to the Cleveland Indians.

Once Boston University purchased Braves Field from the departed Braves in the 1955, they immediately tore down the left-field pavilion; the roofed grandstand at left would soon follow.(Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

The Vanishing Third Act.

The Braves’ fall from pennant-winning glory would be as shockingly fast as their rise to it. The team remained somewhat competitive, but attendance dropped like a rock, back to an abysmal 281,000 in 1952 that even the terrible Braves/Bees teams of the 1930s would have grimaced at. Early that year, Lou Perini told The Sporting News, “I’d rather lose money on the Braves than on anything else I can think of.” But when he lost some $700,000 in 1952 alone—a staggering sum in its day—while watching the Red Sox down the street coast along with healthy attendance, a crackerjack offense and a megastar in Ted Williams, he began to think that maybe losing money elsewhere might be a better alternative.

For a while Perini looked to the suburbs, but he had hoped to rent Fenway Park while a new ballpark was built. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, hoping to see Perini and the Braves just go away, said he wasn’t interested in another tenant.

In 1946, Perini had bought the minor league Milwaukee Brewers to be the franchise’s top farm club. More importantly, he gained the rights to the territory. And when the City of Milwaukee pushed an effort to build, with its own money, a major league-ready ballpark, Perini began to salivate. Other owners—most notably the St. Louis Browns’ Bill Veeck—came knocking on Perini’s door to ask for the territory as a pretext to relocating their team to the new ballpark, but Perini said no. For him, Milwaukee was his future—but he wasn’t going to tell anyone about it, not even his wife.

As the Braves sank deep into the fiscal red in 1952, Perini dove deep into highly secretive negotiations with Milwaukee on a possible move. The Boston media never caught the trade winds, and that kept Braves fans even further in the dark. On September 21, 1952, the Braves lost 8-2 to the Brooklyn Dodgers in a game that, surprisingly, lasted only nine innings. Few if any of the 8,822 fans on hand had no idea that it would be the last game the Boston Braves would ever play at Braves Field.

Braves players themselves wouldn’t even know of the move until spring training, when they were handed caps with “M” instead of “B” stitched upon the front. The news was sudden and official: The Braves were now Milwaukee’s. Beantown was now the full property of the Red Sox, and Braves Field slid into inertia, a ballpark named after a team that no longer called it home.

From the move, casualties abounded. The 1953 All-Star Game, scheduled for Braves Field, was moved to Cincinnati. A block to the south on Commonwealth Avenue, Braves star pitcher Warren Spahn was set to open a diner he had financial co-interest in that would cater to fans taking in a pre- or post-game meal. “My heart will always belong to Boston,” Spahn told The Sporting News after the Braves’ move was announced, “and so will my diner.” But within a year, he cashed out.

The Braves Field site today. Only the right-field pavilion and team office building behind it remains. (Google Earth)

The Nickering Away of Braves Field.

The 37-year-old facility didn’t stay vacant for long—but it also would never be the same. Boston University, whose campus was spreading westward toward the ballpark, purchased it from the Braves, renamed it Nickerson Field, immediately tore down the left-field pavilion and added bleachers in the outfield to forge a fitting alignment for the BU football squad. Football history would be made at Nickerson Field in 1960 when the first-ever American Football League game was played between the Boston Patriots and Denver Broncos. After the Patriots moved down the street to Fenway Park in 1963, more changes came. The main grandstand section, with its massive roof, was eliminated. So was the Jury Box. An artificially turfed football field surrounded by a track took over in 1968. Every budding pro sports league, from the North American Soccer League to the United States Football League to Major League Lacrosse to the Women’s United Soccer Association, all took a shot at Nickerson Field. Few if any of them lasted very long there. Increasingly, the field became more of a recreational facility for BU students to get in their daily exercise routine.

The Braves continue on today, four ballparks removed from Braves Field. Meanwhile at Nickerson Field, the visual clues of yesteryear remain with the right-field pavilion, the ticket office, a historical plaque and, if excavation ever takes place below the field, the remains of a dozen horses and mules—said to be accidentally buried (and never dug up) when the infield dirt collapsed upon them during the ballpark’s construction in 1916.

Chances are, they were as ceremoniously laid to rest as were the Boston Braves.

The Ballparks: Fenway Park It’s crowded. It’s uncomfortable. It’s expensive. And it’s on everyone’s bucket list. With disharmonious angles, unpredictable caroms and wall heights ranging from a pesky three feet to a monstrously green 37, Fenway Park is baseball’s ultimate pinball machine, nearly unplugged more times than a cat has lives before its antiquity became too priceless to abandon. And always remember: When you enter, you’re not merely a spectator—you’re a participant. Have a great time.

The Ballparks: Fenway Park It’s crowded. It’s uncomfortable. It’s expensive. And it’s on everyone’s bucket list. With disharmonious angles, unpredictable caroms and wall heights ranging from a pesky three feet to a monstrously green 37, Fenway Park is baseball’s ultimate pinball machine, nearly unplugged more times than a cat has lives before its antiquity became too priceless to abandon. And always remember: When you enter, you’re not merely a spectator—you’re a participant. Have a great time.

The Ballparks: Turner Field How do you conceive and build a track and field facility for the Summer Olympics, tear it apart afterwards and convert it to a ballpark? Ask the folks in Atlanta, where running tracks became warning tracks, ovals became diamonds, and flags became foam tomahawks. A year after its opening, Olympic Stadium would become Turner Field, and on its stage the Braves would replace the world’s athletes and extend its reign of excellence.

The Ballparks: Turner Field How do you conceive and build a track and field facility for the Summer Olympics, tear it apart afterwards and convert it to a ballpark? Ask the folks in Atlanta, where running tracks became warning tracks, ovals became diamonds, and flags became foam tomahawks. A year after its opening, Olympic Stadium would become Turner Field, and on its stage the Braves would replace the world’s athletes and extend its reign of excellence.

Boston Red Sox Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Red Sox, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.