THE BALLPARKS

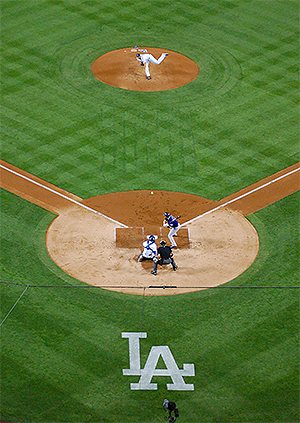

Dodger Stadium

Los Angeles California

(The Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

The City of Angels felt the need to give the Dodgers the best chunk of available real estate in the Southland, literally moving mountains to wedge a jewel of a ballpark into the sloping, sun-baked Earth amid palm trees and Pacific breezes. Within sight of Downtown and the towering San Gabriel Mountains in the distance, it’s a ballpark you can only love but cannot label. It’s not retro. It’s not modern. It’s just…perfect. It’s time for Dodger Stadium.

Some ballparks sell themselves well on TV. Viewers see Boston’s Fenway Park and decide they’ve got to make an appointment to see the Green Monster for themselves. Or the ivy at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Or downtown Pittsburgh from PNC Park. But the Dodger Stadium experience, or the fantasy of it, doesn’t translate well on the screen for those who’ve never been there. Watching from a couch, barstool or bus seat, they might see a ballpark with bland symmetry and no quirks or special points of interest like a swimming pool or locomotive. Dodger Stadium, to them, may look like just another ballpark.

Some ballparks sell themselves well on TV. Viewers see Boston’s Fenway Park and decide they’ve got to make an appointment to see the Green Monster for themselves. Or the ivy at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Or downtown Pittsburgh from PNC Park. But the Dodger Stadium experience, or the fantasy of it, doesn’t translate well on the screen for those who’ve never been there. Watching from a couch, barstool or bus seat, they might see a ballpark with bland symmetry and no quirks or special points of interest like a swimming pool or locomotive. Dodger Stadium, to them, may look like just another ballpark.

If that was the truth, then El Capitan is just another rock.

To understand Dodger Stadium, to absorb its simple perfections, you have to be there. And once you do, you’ll get the picture you don’t see on TV: The cascading parking lots that surround and practically cradle the venue, built not on a flat slab of land but, uniquely, into the side of a hill; the straightforward yet brilliantly realized seating structures, allowing pristine views of the action; and the rich atmosphere of pure baseball, free of faux frills and unnecessary kitsch which can turn any first-time spectator‘s blood into Dodger Blue.

Built over 50 years ago, Dodger Stadium has stood the test of time. It has never felt old or outdated, nor has it been known to be excessively modern or cutting edge. Some may give it a quick glimpse and call it ‘generic,’ while others prefer the term ‘classic.’ But let’s be honest; Dodger Stadium defies description. It is and always has been what it was meant to be, first, foremost and only: A ballpark. It doesn’t matter if the crowds—constantly among the largest in baseball—are coming from the Hollywood mansions, the burbs or the projects; they’re all there to see a ballgame, and nothing more. And because the Dodgers have constantly rewarded them with a winning performance, there’s little reason to seek a side attraction.

The Sad Ballad of Chavez Ravine.

The prescript to Dodger Stadium is mostly tied to the bitter and controversial tale of Chavez Ravine, the land it would be built upon.

A rugged hilly landscape that overlooks downtown Los Angeles, Chavez Ravine was for years home to a tight-knit, mostly poor Latino community. The area otherwise didn’t attract much attention; it was so relatively anonymous, the joke went around that those who’d never heard of Chavez Ravine thought it was the name of a Mexican strip tease dancer.

But as Los Angeles experienced explosive postwar growth, it was decided that Chavez Ravine needed a makeover. The area was originally to be upgraded as a public housing development named Elysian Park Heights—an ironic name, given that the first organized baseball game took place at Elysian Fields in New Jersey—but the project died under the weight of the Cold War and the anti-Soviet furor it engendered, as housing projects were increasingly considered “communistic.” Never mind that most of the existing neighborhood had already been bulldozed.

Under pressure from the Federal Government, Los Angeles politicians were told to develop the property for some sort of public use. Taking that cue, the city leaned in the direction of something recreational, with a proposed ballpark as the prime concept. The first interested suitor would not be the Dodgers—still figuring out their future in Brooklyn—but the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. Bob Cobb, who owned the Stars and the local Brown Derby restaurants (yes, the ones actually shaped like a brown derby), idealized a 30,000-seat facility that according to The Sporting News would include “radiant floor heating, escalators, theater-type box seats…and a Farmer’s Market-type food concession.” That wasn’t all. Cobb also called for the property to include a golf course, indoor arena, tennis courts, swimming pools, a zoo and parking for 30,000 cars. How all of that would fit in less than 300 acres must have been an afterthought.

The view of the game from the fifth-level concourse—the highest point at Dodger Stadium.

When O’Malley traded his minor league territorial rights in Ft. Worth, Texas for those the Chicago Cubs owned in Los Angeles, he was halfway home. The L.A. City Council ensured the other half on October 7, 1957—just two weeks after the Dodgers played what would be their final game at Ebbets Field—by officially welcoming the Dodgers and giving them clearance to build a new ballpark at Chavez Ravine.

Acquiescing was Bob Cobb, who realized his Hollywood Stars would be no match for the incoming Dodgers and graciously stepped aside. Less acquiescing was L.A. citizens who opposed a Chavez Ravine ballpark and generated enough signatures to put the matter to a vote, not because of the money (O’Malley was going to finance Dodger Stadium from his own wallet) but because they claimed the land was preserved for public recreation—and the Dodgers, a private organization, didn’t count toward that. Far, far less acquiescing would be the remaining residents of Chavez Ravine, who were ready to aggressively hold onto to their properties come hell or high court eviction notices.

The campaign for and against Dodger Stadium was bitterly waged. Anti-ballpark foes complained that calling the measure Proposition B was unfair because “B” stood for ‘ballpark’ and thus constituted some sort of free publicity in favor of the measure. The pro-ballpark forces, sweating out a possible close outcome as the vote drew near, held a five-hour TV show—a telethon, really—in support of the measure, a program that included O’Malley and numerous Hollywood celebrities. On June 3, 1958, a record turnout of voters cast their votes; a bare majority of 51.8% gave their approval for Dodger Stadium to be built.

The fighting continued after the vote, with no less than six lawsuits filed in the wake of Proposition B’s passage. One made it to the California Supreme Court, where it lost by a 7-0 count. “First shutout of the season,” bragged O’Malley.

The more ominous battle continued to be fought in the trenches where the ballpark would be built. Eleven remaining Chavez Ravine homeowners defiantly held their ground, rejecting a combined $93,000 in carrot stick money from the city to scat; at one point, O’Malley offered to sweeten the pot five-fold, but still the residents held firm. One of them was literally dragged out of her home by County sheriffs while bulldozers, ready to begin demolishing, idled patiently nearby. Another pitched a tent on his destroyed home and vowed to stay, managing as long as he could because he was accompanied by a loaded shotgun. Another resistant family drew enough sympathy from outsiders, some of whom brought in supplies to help them stay. But even with the doors boarded and nailed shut, authorities barged in and dragged them out. The sob story, reaching nationwide proportions, soured when it was discovered that the family actually owned 11 other homes in the Los Angeles area.

Until a statue of Jackie Robinson was introduced in 2017, the closest thing to something similar at Dodger Stadium was a series of numbers worn by Hall of Famers and retired by the Dodgers, modeled in the team’s familiar red jersey numerals.

The Taj O’Malley.

O’Malley’s initial vision for Dodger Stadium was a more focused variation on the recreational paradise Bob Cobb had dreamt up—and not too different from the “ballpark villages” being built in the 21st Century. He conceptualized a mall, a plush restaurant atop the upper deck with views of both the ballgame and downtown L.A., novelty and souvenir shops, drive-thru ticket booths, an auto repair shop, car wash, a tram that would ferry fans from the farthest reaches of the parking lots, and a water fountain display behind center field that would feature dancing colored lights—a thought the Kansas City Royals would later tap into for Kauffman Stadium. All this Disneyana would be curtailed by the City Council, who told O’Malley to pump the imaginary brakes and leave Dodger Stadium as a place for baseball—and nothing more.

A solid architectural team for Dodger Stadium was officially led by New York-based “Captain” Emil Praeger, known for designing a concrete floating breakwater used to unload Allied supplies onto Omaha Beach following the D-Day invasion; he also blueprinted the Dodgers’ spring training facility in Florida and would eventually draw up Shea Stadium. Joining him was L.A. architect Edward Fickett, a prolific architect of homes—designing everything from affordable housing communities to lavish estates of the stars. While Praeger focused on the Big Picture, it was Fickett who gave Dodger Stadium its clothing through pastel-colored seats and interior embellishments, all decidedly Californian in style. O’Malley himself was a hands-on participant in the process, making many suggestions that would work its way into the final product, dubbed by some as The Taj O’Malley.

Whereas most ballparks are built upon a flat expense, Dodger Stadium would pose the challenge of being placed onto a more undulating terrain. Construction crews moved eight million cubic yards of earth in order to grade the hillside around the ballpark; the resulting topography consisted of a gentle slope that rose from a low point behind the bleachers to an apex 120 feet higher at the other end, allowing those parking behind home plate to literally walk upon the concourse of the upper deck without so much as climbing a handful of steps. Which leads to this important tip: When parking at Dodger Stadium, grab a spot that’s at the same elevation as the entry gate of your level. Otherwise, you might be in for a climb. For example: If you nab a space at field level near the bleachers and have a fifth-level ticket, you’ll end up hiking around the side of the ballpark in what seems an endless parade of steps. (The Dodgers give a little push at the end of the climb by providing an escalator for those potentially in need of oxygen once reaching the top.)

Fans with upper-level tickets need to know where to park in Dodger Stadium’s altitude-divergent parking lots—or they may be in for a long climb.

The architects would clearly and correctly do their homework when it came to Dodger Stadium’s seating arrangements. The field level would be closely topped by a loge section which, even today, remains the majors’ best second-level viewing—so low and close that at times you feel like you are seated in the first deck. A petite third level, hung under an expansive fourth deck, has since been converted into luxury boxes. Finally, a sky-high fifth level stretches from first to third base and sometimes provides the game’s most exciting moment for those seated there when a towering pop fly manages to rise above their eye level.

Behind the outfield walls, two sets of bleacher pavilions are each topped by a useless accordion roof that has the look of a postwar Grapefruit League grandstand and hardly reaches outward to provide shade to spectators. Nevertheless, it has evolved into one of Dodger Stadium’s more recognizable features.

Another early signature element of Dodger Stadium would be its sub-level dugout boxes, placed between the team dugouts behind home plate. O’Malley loved the idea ever since he saw something similar in Japan while the Dodgers toured there, and insisted it be included in the new ballpark.

One of the dugout boxes’ most memorable occupants was Mike Brito, a Cuban-born Dodger scout who for over 20 years showed up clad in his Panama hat, pastel-colored suit, sunglasses (day or night), cigars and radar gun to capture the speed of every pitch. Brito became a familiar ornament in the background of any Dodger Stadium telecast until the team removed the dugout seating in 1999, but he remained a heralded scout, landing the Dodgers top Latin American talent from Fernando Valenzuela to Yasiel Puig.

Dodger Stadium in 1967. Note the dugout seats behind home plate, which were removed in 1999. (Flickr—Blake Bolinger)

The Oval Stopgap.

As construction commenced at Dodger Stadium, the Los Angeles Dodgers had to seek temporary quarters elsewhere in town. The only existing ‘ballpark’ in the area, Wrigley Field—no, not that Wrigley Field, but the one in central L.A. built by Cubs owner Phil Wrigley in 1925 as he also owned the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels—was a non-starter for O’Malley because of its small (20,000) capacity. Seats, lots of seats, was what O’Malley sought in the interim to increase revenue and help pay off the new ballpark—and he found a whole lot of seats at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, which held over 90,000 people.

One problem: The Coliseum was an oval facility designed for football, soccer and track and field. Wedging a ballfield into its available playing space was bound to lead to a disproportionate experience unlike anything seen in baseball. There was give—it was a mere 250 feet to a 42-foot left-field screen that resembled a driving range net—and there was take, with right field opening out some 440 feet out to the far end zone. Not surprisingly, over 80% of the home runs hit at the Coliseum departed over the left-field netting. It didn’t matter to the fans, some of whom sat as far as 700 feet away from home plate in the cavernous facility; they welcomed major league baseball to the West Coast by clicking the Coliseum’s turnstiles eight million times over the Dodgers’ four years there. And it certainly didn’t matter to O’Malley, happily running all the way to the bank with baseball’s biggest profits of the day.

Besides the Coliseum lucre, O’Malley had to find additional revenue to help pay off the $20 million bill on Dodger Stadium. He found an investor in Union 76, an oil company which gave the Dodgers $11 million in return for exclusive ballpark and broadcast ad rights over a 10-year period. Thus, in stark contrast to the bulletin board-like advertising that saturated Ebbets Field’s outfield walls, the only plug to be found at Dodger Stadium was the orange Union 76 logo atop the two hexagonal outfield scoreboards, like a cherry atop a cake. The Dodgers even allowed Union 76 to plant a gas station in the parking lot, and even though it closed in the mid-2000s, the partnership between the Dodgers and 76 continues to this day.

Dodger Stadium’s bleachers, topped by its familiar accordion-shaped roof, which only a few home runs have hit off the top of; only a few have completely cleared it.

Pitch Perfect.

Nineteen months after the first shovels hit the ground, Dodger Stadium was ready to play—but it nearly missed its Opening Day 1962 deadline when heavy winter rains played havoc with last-minute construction details. O’Malley went through the expense of prying away an engine from a F-84 fighter jet to dry-blast the wet, muddy grounds; the grass was still far from ideal days before the first game, and it took a nice paint job (as suggested, it was said, by Hollywood director Mervyn LeRoy) to make it look fresh and healthy.

When the Dodgers, Cincinnati Reds, and 52,564 fans showed up for the inaugural game at Dodger Stadium, a few other embarrassing details were exposed. No drinking fountains. No batting cage. No electrical outlets in the clubhouse. Directional signs were misspelled. And someone pointed out that the foul poles were in foul territory, which at first thought makes sense—except that they’re normally placed right on the foul line to indicate a fair ball if struck. The Dodgers didn’t get around to righting that wrong until the next season, when the field was adjusted to fall in sync with the poles.

Dodger Stadium would secure a reputation as a pitcher’s park soon enough, but the Dodgers’ bats found little trouble producing strong numbers in the ballpark’s first year; the 409 runs they scored would be the most at Dodger Stadium until 2006 as they finished 54-29 at home. Yet that 29th loss would be the most painful, the rubber match of a three-game season extension against the rival San Francisco Giants that ended in a heartbreaking 6-4 loss when they conceded four ninth-inning runs. It was an eerie echoing of the Dodgers’ similar, more legendary three-game playoff loss back east against the Giants and Bobby Thomson, 11 years earlier.

The success of the Dodgers’ hitters in their Dodger Stadium debut would quickly prove to be an anomaly. In the following years, the offense for both the Dodgers and their opponents—so lively back in cozy Ebbets Field—was shut down at the new ballpark by a combination of factors, primarily the cool (but pleasant) evening ocean breezes and the expansive, purely symmetrical field dimensions that favored the pitcher, with center field and the power gaps initially measuring 410 and 380 feet, respectively, from home plate. Those distances have been slightly tinkered about a few times over the ballpark’s life, but by and large it still remains a house that brings smiles to Los Angeles pitchers. Guys like Sandy Koufax, who generated unbelievable lifetime numbers at Dodger Stadium—a 1.37 earned run average, 57-15 record, 23 shutouts, two no-hitters and a perfect game. Or Koufax’s 21st-Century heir apparent in Clayton Kershaw, who’s won two Cy Young Awards and four ERA titles with the help of the ballpark. Or Don Sutton, who tops the charts as Dodger Stadium’s winningest pitcher with 126 victories. Or Fernando Valenzuela, an overnight sensation in 1981 who helped the Dodgers tap into a voluminous Latino market and, for what’s it worth, softened the memories among older Hispanics over the Chavez Ravine row. Or the guys who fashioned baseball’s two longest streaks of consecutive scoreless innings: Orel Hershiser (60) in 1988 and Don Drysdale (59.2) in 1968. The majority of those streaks—36 innings each—were accomplished at Dodger Stadium.

This is not to say that the pitchers have monopolized the book on Dodger Stadium’s greatest moments, or that hitters haven’t found success there. The late, great Roberto Clemente hit .377 in 79 games at Chavez Ravine. In 1999, Fernando Tatis of the St. Louis Cardinals hit two grand slams at the ballpark—in one inning. Four players have hit baseballs completely out of the park: Willie Stargell (who did it twice), Mark McGwire, Mike Piazza and Giancarlo Stanton. But the greatest home run—and unarguably the single greatest moment in the history of Dodger Stadium—took place in the first game of the 1988 World Series when a hobbled Kirk Gibson muscled out a game-winning home run against the mighty Oakland A’s and impenetrable closer Dennis Eckersley, setting the tone for the Dodgers’ five-game Series triumph, their last to date.

In the early 2010s, Dodger Stadium’s concourses were widened to allow fans better movement; tables and “drinking rails” were also provided to foster a lounge-like environment.

The “Other” Team.

Initially, the Dodgers were not the only major league team to call Dodger Stadium home. The Los Angeles Angels, born as an American League franchise in 1961 and not to be confused with the former PCL team, gave Wrigley Field West a shot in their inaugural campaign and didn’t care for it. So the Dodgers allowed the Angels to share Dodger Stadium from the park’s first year through 1965; it was a four-year experience the Angels would barely manage to tolerate.

Officially referring to the Dodgers’ new home as Chavez Ravine Stadium, the Angels drew 1.14 million fans in their first year there—a gratifying figure but still less than half what the Dodgers drew—and most of the folks who showed up seemed more interested in the Dodgers, as broadcaster Vin Scully’s voice echoed through the ballpark via numerous transistor radios brought in by fans tuning into Dodger games. Players on the field found themselves confused by the occasional untimely cheer—before being told that the fans’ ears, and thus their minds, were focused on the road with the Dodgers. Angels attendance at Chavez Ravine sloped downward from their 1962 debut at the park, all the way to 566,000 in their last season; for one late 1963 game, they drew a crowd of just 476—the smallest in Dodger Stadium history. Between all of the above and complaints of having to pay too much of the ballpark’s maintenance bills, the Angels were more than happy to escape their second-class status and move 40 miles south to Anaheim Stadium starting in 1966.

Angels or no, the Dodgers became a box-office smash in their early years at Dodger Stadium, bringing in more profits for Walter O’Malley; the franchise became so awash in money that O’Malley never felt inclined to raise ticket prices, as a box seat remained $3.50 from Dodger Stadium’s first year all the way through its 19th (in 1980). That they continued to win certainly didn’t hurt; they took world titles in 1963 and 1965 while grabbing another NL pennant in 1966. Dodger Stadium didn’t always sell out—a tough task back in the day with 56,000 seats—but still O’Malley entertained the idea of upgrades. The ballpark was designed to expand to a capacity of 85,000, but a more sensible scenario saw the stretching out of the upper deck to wrap around the foul poles and match the length of the lower levels—as it had been originally planned, per the architect’s models and sketches—but the basic structure has remained the same. For good reason.

Another idea relegated to the architect’s “what if” folder was the addition of a dome. That concept was deemed too expensive, to say nothing of unnecessary; at Dodger Stadium, it’s never too hot, never humid, seldom chilly and it almost never rains there. In the ballpark’s first 14 years, there was only one rainout. In April 1988, three straight games were postponed by wet weather—and then it didn’t rain again until 1999. Since the washout of a game on April 17, 2000, there hasn’t been a single rainout at Dodger Stadium—a streak of nearly 1,300 games that’s the longest among outdoor facilities in major league history.

Heavy rains—and we mean, heavy—turned Dodger Stadium’s playing field into a virtual lake on September 18, 1965. Pity the poor Angels, who had a game scheduled and were made to suffer; and no one suffered more than the Angels’ batboy, who was told to swim into the dugout and retrieve the team’s equipment. Hopefully he got a nice tip—and a set of dry clothes.

Hitting Full Stride.

As Dodger Stadium settled into a routine for Southlanders, traditions evolved. There was, of course, the reputation of Dodger fans who showed up in the third inning because of the freeway traffic and left in the seventh to avoid getting caught in it again. There was the electronic drum roll that chattered every time the Dodgers scored—something that irritated Bay Area fans watching Dodgers-Giants games on TV to no end. And there was Roger Owens, so popular as a long-time vendor who dazzled fans with his long-distance, acrobatic and accurate tosses of peanut bags (and hoping he got his money from equally afar in return) that he got a book of his life published and was once invited to chuck peanut bags at President Jimmy Carter’s inaugural party—although the Secret Service wouldn’t let him to do his thing because the bags weren’t X-rayed for security purposes.

While Owens was the most popular deliverer of food, undoubtedly Dodger Stadium’s most popular food, period, was, is and always will be Dodger Dogs. Almost impossible to miss in the concourses, the long, skinny wieners have been a tasty favorite and craved by fans and players alike; in the early 1980s, the Dodgers’ Jay Johnstone—an oddball among oddballs—once left the dugout shortly before a game and walked through the stands in full uniform to get in line and grab one.

Prime seats were added behind home plate and along the foul lines in 2005, reducing foul territory and bringing fans with deep pockets closer to the action. Look closely and you might find Mary Hart or Larry King.

Through it all, the winning has continued. After the Dodgers hit a dry spell in the late 1960s following Sandy Koufax’s retirement—with some Dodger Stadium crowds dwindling down below 10,000—good times returned along with the fans in the 1970s with a new wave of talent. It included an eternal foursome of infielders who would play regularly together for nine straight years: First baseman Steve Garvey, the only player to collect over 1,000 hits at Dodger Stadium; shortstop Bill Russell, the only guy to play over 1,000 games; third baseman Ron Cey; and second baseman Davey Lopes. During this foursome’s reign, the Dodgers won four more pennants (including a world title in 1981) and brought attendance back over two million and, in 1978, three million—the first time a major league team had cracked that barrier.

The glorious (albeit strike-shortened) 1981 campaign, well remembered for the “Fernandomania” that swept Dodgerland thanks to 20-year-old Mexican-born pitching sensation Fernando Valenzuela, increased the Latino presence at the ballpark for the long term and helped maintain Dodger Stadium attendance at and over the three-million mark. After the turn of the Millennium, the barrier was pushed further as the Dodgers neared four million; if they sold out every game—a tall task but still quite possible—they could easily surpass the four million mark and challenge the all-time attendance figure of 4,483,350 set by the 1993 Colorado Rockies.

Unfortunately, not all of the fans coming to Dodger Stadium have been on their best behavior in recent years. Starting in the 1990s, there was an unnerving increase in the presence of the gang element, which caused problems in the ballpark and, especially, outside in the dark, vacuous parking lots. This was never more alarmingly illustrated then on Opening Night 2011, when Giants fan Bryan Stow was severely beaten up by a pair of thugs in the darkened parking area after the game. The assailants would eventually be arrested and convicted, but that provided little comfort for Stow, who suffered major brain damage and is permanently disabled. The Dodgers have since gone to great pains to curtail the problem; they’ve hired on enough police to patrol the park, correctly striking a balance from which people feel safe without sensing a police-state environment. But law-abiding fans have been inconvenienced as the Dodgers, in an attempt to minimize potential for outside trouble, have banned all tailgating in the parking lots.

There’s been an increase in the representation of Los Angeles’ finest throughout Dodger Stadium, a reaction to the poor (and sometimes violent) fan behavior in recent years. By and large, the fans are very well behaved.

Maintaining the Newness.

Dodger Stadium sat largely undoctored through its first 40 years, save for a yearly repainting of the joint (to keep it looking new) and the replacement of the original wooden seats in 1975 in favor of more brightly colored plastic ones. But the removal of the dugout boxes in 1999 began a period of continued upgrades. A new video board was installed in 2002 and, three years later, the seats were yet again replaced, going back to the original pastel look. At the same time, a more comprehensive renovation took place as the field level was extended closer to the field—but when fans sitting in the pricey new seats complained of flattened sightlines, the Dodgers quickly went back to the drawing board and not only re-angled the seats for better viewing, they also reconstructed the area to include counter-like tables for fans to place their food and drinks upon.

In 2008, Dodgers lord Frank McCourt—two owners removed from the O’Malley family (in between, there was Fox)—envisioned a massive $500 million renovation of Dodger Stadium with a target completion date of the ballpark’s 50th anniversary in 2012. The ballpark bowl itself would be largely untouched; it was the surroundings that would be wholly reinvented. The project called for two plazas—one an airy, shaded expanse behind the upper deck, the other an even more spacious row of shops topped by a wavy roof behind the more accordion-like bleacher tops. The latter plaza would be separated in two by a grand pedestrian walkway where many fans would enter, ideally via mass transit options as the Dodgers, thinking green as well as blue, were emerging as environmentally-friendly players. Adding to the green theme, the sides of the ballpark would be heavily enhanced with a vernal paradise of trees, walkways and plants, as if fans would be walking through an expanded botanic garden. All in all, it was a modern, more environmentally friendly take on Walter O’Malley’s original vision of a ballpark village, with the idea to get people to show up before the third inning and keep them around after the seventh. This grand ambition would fall victim to the Great Recession and the divorce of McCourt and his wife, both of whom were battling for control of the franchise—which temporarily went bankrupt as a result.

After McCourt sold in 2012, the Dodgers’ new owners—a deep-pocketed group backed by Guggenheim Partners which included basketball legend Magic Johnson, baseball executive Stan Kasten and Hollywood mogul Peter Guber—considered building a football stadium alongside Dodger Stadium as McCourt had quietly tried to do in 2005; they also explored the idea of, gulp, abandoning Dodger Stadium for a whole new multi-facility sports complex elsewhere in town—all in the name of luring pro football back to Los Angeles. They settled, instead, on a more Spartan version of McCourt’s upgrade plans, enhancing the experience of watching the game as opposed to enhancing it outside.

Under the supervision of Janet Marie Smith, the visionary catalyst for Oriole Park at Camden Yards and other recent ballparks, the $150 million renovation would reward the common fan over those already spoilt in the luxury boxes. The concourses were expanded to relieve congestion and would include “drinking rails” to encourage fans to mingle and watch the action away from their seats, if they so choose. Team merchandise stores were added at the upper level entrance and behind the outfield corners. Children’s play areas were set up for young kids not yet ready to sit patiently through nine innings. Wifi access was significantly upgraded. And for the players, the clubhouse area was greatly expanded and modernized, and now even includes a “quiet room” to chill out from any surrounding drama.

Fans sitting closest to the action not only get wider seats but also a convenient counter for which to place their food, drinks and other objects upon.

Of Rock and Ice.

Shaped like a ballpark but officially referred to as a stadium, Dodger Stadium has nonetheless served multiple purposes. The biggest names in music have all performed there, including Elvis Presley, the Jacksons, U2, the Three Tenors and Madonna. The Beatles played their penultimate concert at Dodger Stadium (that is, if you don’t count their rooftop performance from Let It Be). In January 2014, KISS played a short set as the warm-up act to one of the more unlikely “Winter Classic” hockey games ever staged, as the Los Angeles Kings and Anaheim Ducks played before 54,000 fans; fortunately, the band’s signature pyrotechnics didn’t melt the nearby playing ice any more than the 62-degree weather would at the first drop of the puck. But perhaps the most memorable gig ever played at Dodger Stadium came in 1975 when Elton John, at the height of his early pop days, took to the stage on successive days before sellout crowds and brought the house down, wearing a glammed-out Dodgers uniform with “Elton” and the number 1 on the back.

The Dodgers also haven’t held the monopoly on baseball events at their venue, beyond its early use by the Angels. Dodger Stadium hosted a portion of the baseball competition during the 1984 Summer Olympics, and was the scene for the 2009 World Baseball Classic final.

It’s so 1962.

There’s so much about Dodger Stadium that’s old school. In a time when major league teams are opting for smaller, more intimate facilities, Dodger Stadium—which at one time had the majors’ 11th largest capacity—now holds more seats than any other MLB ballpark. While others want to make life miserable for outfielders with odd-shaped field dimensions with all the predictability of a pinball machine, Dodger Stadium has emerged as the only current ballpark using a purely symmetrical outfield. The Dodgers don’t mind. In fact, they crave the ballpark’s throwback to bigger, more balanced environments of jet-age lore, and it’s apparent throughout the venue today.

The pale industrial blue that dominated 50 years earlier is back, as much of the structure is dressed in a combination of vertically striped aluminum siding and warm beige concrete bricks. Inside, the walls are dotted here and there with simplistic, retro-themed illustrations accompanied with messaging spec’d out in an intentionally dated use of informal script and Futura type. There are no statues to be found of legendary Dodgers, but there are six-foot-tall bobbleheads outside the gates that look like Speedy from those 1960s Alka Seltzer commercials, posing for photos with arriving fans while Vin Scully’s folksy voice bounces about from tinny, nearby speakers in a looped greeting, capped with his signature phrase, “It’s time for Dodger baseball.” It’s all so 1962.

In a nostalgic ode to its infant years of the early 1960s, Dodger Stadium has recently been embellished with retro-flavored signage to bring the innocent kid out of everyone.

You can see some or all of this at Dodger Stadium, depending on where you sit. Unfortunately, not everyone can be allowed everywhere. Fans with tickets for the upper two decks are, technically, not allowed to go down to the levels below. Those with bleacher seats pretty much have to stay where they are; those sitting behind the left-field wall can’t even access the right-field pavilion, because those are the folks who get served with the “All-You-Can-Eat” menu of hotdogs, nachos, popcorn, peanuts, soda and water. The fans willing to fork out good money to sit in the field and loge levels get virtual access throughout the park—and this includes allowance into the suite level, the closest thing to a Dodgers Hall of Fame with a long hallway full of mementos including posters, jerseys and artifacts of generations gone by, all the way back to the franchise’s Ebbets Field days.

Dodger Stadium was made for the evening, and the Dodgers get that—that’s why they schedule so few day games. Views abound, from the emerging lights of downtown Los Angeles behind the upper deck entrance to the tall, rugged San Gabriel Mountains off to the north—more visible these days as the infamous smog that once choked the basin has eased with tougher environmental laws—and as the sun sets, the palm trees standing tall beyond the bleacher pavilion rooftops form a comforting silhouette against a vibrant sky full of blues, reds and violets, as if borrowed from the side of an airbrushed 1970s van. In a town where typecasting can run rampant, you can’t pigeonhole Dodger Stadium; it remains a timeless structure—now the third oldest active in the majors—that is sure to last for the long run. For the fans relaxing amid mild Pacific breezes and watching their Dodgers win yet again, there is no feeling of ill comfort, of sitting in a rotting house. Some might say that everything old is new again at Dodger Stadium. But it really never has been old. Or even new. It just is.

And that might just be the ultimate complement.

The Ballparks: Ebbets Field There was nary a dull moment at the fabled ballpark, a funhouse where the rabid fans were almost as famous as the players, so close to the action that fielders could almost feel the vocal gusts of their breaths. From the jolly comic antics of the Robins to the breakout Bums of the 1940s to Jackie Robinson and the Boys of Summer in the 1950s, Ebbets Field was more than just the heart and soul of Brooklyn; it was Brooklyn.

The Ballparks: Ebbets Field There was nary a dull moment at the fabled ballpark, a funhouse where the rabid fans were almost as famous as the players, so close to the action that fielders could almost feel the vocal gusts of their breaths. From the jolly comic antics of the Robins to the breakout Bums of the 1940s to Jackie Robinson and the Boys of Summer in the 1950s, Ebbets Field was more than just the heart and soul of Brooklyn; it was Brooklyn.

Los Angeles Dodgers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Dodgers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.