The Ballparks

The 1860s-1900s: Lumber and Crossed Fingers

From open pastoral settings to medieval frameworks, the 19th-Century ballpark endures through a fragile evolution as the use of wood lead to multiple hazards, most occasionally that of fire.

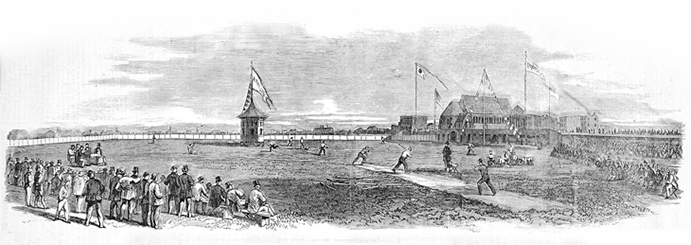

In 1862, Brooklyn’s Union Street Grounds became the first enclosed ballpark; it may have also been the last one to include a permanent structure in the middle of center field, as the pagoda here shows. (Harper’s Weekly)

Baseball emerged from its ancestral roots in the 1840s, becoming wildly popular in New York City and other Northeast points on a recreational level through the start of the Civil War. Amateurs and pickup teams flooded parks and other flat expanses to perform in front of handfuls of friends, family and curious onlookers, much as you might see at a little league game today—minus the dugouts, fencing and perhaps the rudimentary bleachers. Ultimately, the mania led to the smell of money permeating the sport, which led to professional teams, which led to professional leagues, which led to facilities to house those teams.

The first true ballpark, Brooklyn’s Union Street Grounds, was established in 1862 when the owner of a large outdoor skating rink wanted to find additional revenue streams once the ice melted. So he configured the rink to a baseball field, enclosed it with a fence and added benches for spectators who initially didn’t have to pay to enter. Outside of an immovable pagoda (which skaters encircled in the winter) sitting in short center field, the players found the place just fine.

The instability of the early major leagues was matched by the fledgling quality of their ballparks. Most structures were crude and often consisted of a single, straight grandstand compared to the more familiar V-shape that hugged the base lines. The playing fields themselves were often an adventure; outfielders, some playing without walls behind them, had to contend with slopes, trees, swamps, lakes and dangerous debris left over from the garbage dumps some ballparks were built upon. The original Polo Grounds in New York featured two fields, each backing up against one another; it wasn’t uncommon for an outfielder’s concentration to be disrupted by an invading ball—and the player in pursuit of it—from the game behind him. When the city decided to build a road through the park in 1889, it left the New York Giants—suddenly without a home—to briefly play at a roughened facility on Staten Island that included an off-Broadway stage in right field. The actors hung out on stage during the games, not so much to watch but to protect the props from an incoming drive.

There was a tremendous discrepancy in field dimensions depending on where one played, as the modern-day 330-400-330 average in right-center-left had yet to be fully grasped. At some early ballparks, the center field wall—or rope, or pond or imaginary line—went out as far as 600 feet from home; down the lines, they could measure less than 200, leading to ground rules where cheap home runs were declared to be doubles. In 1884, the National League’s Chicago White Stockings (later the Cubs) dared to waive the homer-as-double statute at Lakefront Park, where the left-field wall sliced to a mere 180 feet down the line from home plate. The result: After being credited with 13 home runs the year before, the White Stockings blasted 142, with four players topping 20—including 27 from Ned Williamson, establishing a major league record which held until Babe Ruth came along over three decades later.

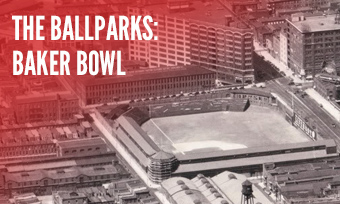

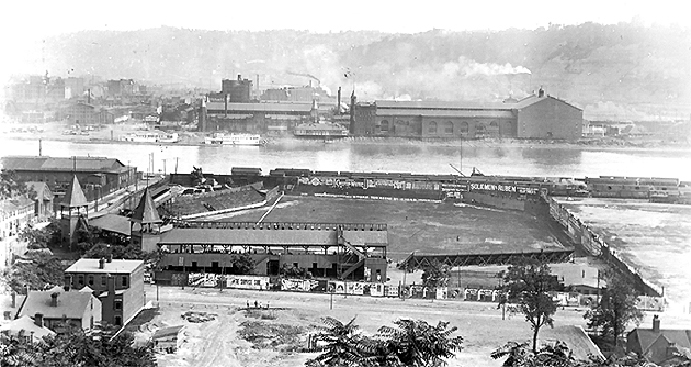

Starting in the late 1880s, the standard grandstand structures of the early ballparks began to segue to those with more architectural muscle. Boston’s South End Grounds, Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park and Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl used medieval motifs such as spires and turrets as their signatures, with main gate facades more befitting to Camelot than American baseball. The castle chic ran its course at the Turn of the Century when Cincinnati’s short-lived Palace of the Fans brought a decidedly neo-classical look that would influence the next 20 years of ballpark architecture.

Exposition Park in Pittsburgh, built in 1890 along the Allegheny River, was one of many late 19th-Century ballparks influenced by traditional European architecture as shown here with the use of twin spires to grace its main entrance.

Some ballparks didn’t lack for frills and laid the ancestral roots for the ballparks of today. Lakefront Park in Chicago had “private” boxes placed atop the grandstand roof while the Palace of the Fans had them at field level, large enough for fans to pull their car or buggy up to; these were the first idealizations of the luxury box. And in 1882, the American Association’s St. Louis Browns built the first version of Sportsman’s Park and retained an existing two-story house near right field, transforming it into a beer garden complete with handball courts and lawn bowling; for its first seven seasons, the garden was in play as outfielders occasionally elbowed and excused imbibers in pursuit of a live ball—and perhaps a quick sip. Rebuilt in 1891, Sportsman’s Park preceded Toronto’s Skydome by becoming an all-in-one entertainment center including an amusement park, a roller-coaster bicycle track and other sideshows—ruffling the feathers of other owners who preferred to concentrate more on baseball.

The biggest problem for ballparks in baseball’s emerging years could be summed up in a single word: Wood. Essentially every ballpark through the late 1900s was built almost entirely of lumber—and once paired with intense heat in the form of a lit match, overheated machinery or lightning, flames were sure to ensue. Fires were a common occurrence, and it was most frightening when a game was taking place. The scariest such moment came in 1894 when, in one of four fires to burn up a major league ballpark that season, players in Chicago rescued fans trapped within the burning West Side Grounds by using their bats to pry open fencing separating the stands from the field.

While mass casualties never resulted from all the fires, it was ironically Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl—the first ballpark to eschew wood and be built mostly of steel and brick—that would cause the majors’ most tragic accident in 1903 when an overhang behind the third base side collapsed from the surge of hundreds of fans who turned their backs on a game to watch a street fight below; twelve were killed and over 200 injured. The primary material used to build the overhang? Wood.

The continuance of fires begged for a new wave of ballparks that would prove stronger, safer and more fireproof. That was made more likely with the 1901 introduction of the American League and the resulting surge in popularity the two leagues enjoyed as respected rivals, peaking each year with the World Series.

Forward to the 1910s-1920s: Steel and Concrete Baseball’s modern era comes of age with the help of the sport’s first ballpark boom, as sturdy, cutting-edge palaces show off grace and confidence to mirror the game’s growth.

Forward to the 1910s-1920s: Steel and Concrete Baseball’s modern era comes of age with the help of the sport’s first ballpark boom, as sturdy, cutting-edge palaces show off grace and confidence to mirror the game’s growth.