The Ballparks

The 1930s-1950s: Dormancy

Depression and war embolden the general attitude of most major league teams to contentedly sit it out at their existing ballparks, which undergo expansion and are outfitted with lights for the night.

Behemoth Cleveland Stadium was the only new facility built for a major league team in the 30 years after Yankee Stadium’s debut—and even then, it took the Indians 15 years to fully embrace the multi-purpose venue. (Associated Press)

Following the debut of Yankee Stadium, the majors set upon an extended period of entrenchment. For the next three decades, baseball stayed put. There was no expansion. No relocations. No new ballparks. Change might have been on the menu, but the majors had to weather a few major storms in the Great Depression and World War II, events that further immobilized any attempt by the 16 teams to relocate or totally reinvent.

There was one slight exception in Cleveland, which built monstrous Cleveland Stadium—but even the Indians trod lightly at first, unsure if the 80,000-seat multi-purpose facility was right for them. They remained unsure for 15 years, bouncing back and forth between the stadium and cozy League Park; finally, in 1947, the Indians went all in and made Cleveland Stadium their permanent home.

Expansion, such as the one above at New York’s Polo Grounds, was a common sight as the steel-and-concrete ballparks aged toward mid-century. Note the fans being allowed to sit in sections still under construction. (Library of Congress)

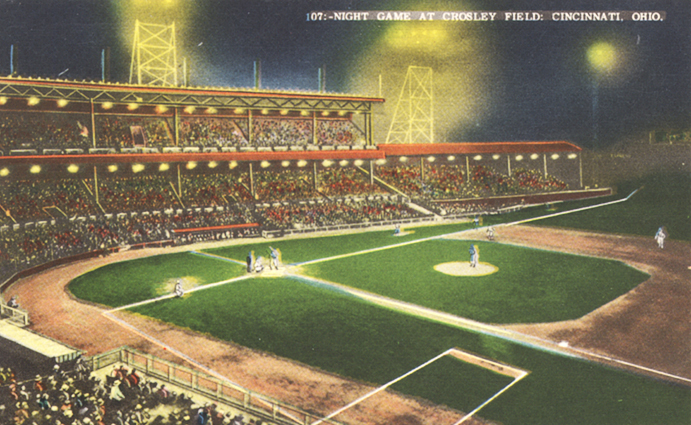

The other 15 teams stayed put as their steel-and-concrete ballparks hit middle age, resorting to cosmetic surgery as the primary upgrade option. Renovation ran constant throughout this period as numerous expansions raised the average major league capacity from 28,300 in 1923 to 43,800 in 1952. Field dimensions were tightened from the near-boundless extremes of the Deadball Era as a kneejerk reaction to the high-octane offense of the 1920s and 1930s that lit up scoreboards and the box office. Fenway Park was essentially rebuilt after Tom Yawkey bought the Red Sox in 1933, introducing baseball fans to the famed Green Monster in left field. At Wrigley Field, ivy was planted on the outfield wall for the first time. And in 1935, there was light; Cincinnati’s Crosley Field became the first ballpark to lamp up and play ball at night. Within 12 years, all other ballparks—except Wrigley—followed suit.

Night baseball debuted in the majors when Cincinnati’s Crosley Field lit up for the first time in 1935. Within 12 years, every big-league ballpark—except Chicago’s Wrigley Field—erected lights for evening games. (The Rucker Archive)

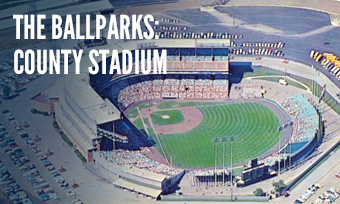

By 1953, the American Northeast’s grip on major league baseball began to loosen up. Everyone saw it coming. In the postwar glow of prosperity, Americans stretched out and took the emerging Interstates and air travel routes to points south, west and way out west. Cars and houses became more affordable, the suburbs became trendy and the inner cities were left behind, threatened with accelerated decay. Baseball owners were hardly blinded to all of this and sought out greener pastures, both in terms of land and money. The Boston Braves started it all by moving to Milwaukee, where they became an instant success in the standings and at the bank; on the Braves’ heels, two other bottom feeders—the St. Louis Browns (to Baltimore) and Philadelphia A’s (to Kansas City)—also left town over the next few years. The ballparks inherited by these transplants were, like Cleveland Stadium two decades earlier, relatively new (or recently renovated, in Kansas City’s case), publicly paid for and architecturally uninspiring. The aesthetic bells and whistles would have to wait for another time; the citizens who helped front the bills for these civic projects craved only functionality to get a return on their investment.

The aforementioned moves were considered nothing more than geographical corrections as struggling franchises escaped two-team cities in an effort to ensure simple survival. But the dormancy period was shattered in 1958 with a shocker that was sure to shake the cobwebs off the status quo: The moves of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants, two esteemed ballclubs hardly buried in financial dire straits, to California.

Forward to the 1960s-1980s: The Cookie Cutter Monsters Multi-purpose stadiums become the rage as a line of enclosed facilities adaptable to disparate events welcome in baseball teams fleeing decaying ballparks and inner cities.

Forward to the 1960s-1980s: The Cookie Cutter Monsters Multi-purpose stadiums become the rage as a line of enclosed facilities adaptable to disparate events welcome in baseball teams fleeing decaying ballparks and inner cities.

Back to the 1910s-1920s: Steel and Concrete From open pastoral settings to medieval frameworks, the 19th-Century ballpark endures through a fragile evolution as the use of wood led to multiple hazards, most occasionally that of fire.

Back to the 1910s-1920s: Steel and Concrete From open pastoral settings to medieval frameworks, the 19th-Century ballpark endures through a fragile evolution as the use of wood led to multiple hazards, most occasionally that of fire.