The Ballparks

Forbes Field

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

(Underwood Archives)

Removed from downtown Pittsburgh’s choking smoke and untamed rivers, elegant Forbes Field was built in a vernal, cultural paradise on the outskirts of town, where three was the magic number—from three Pirates world titles to Babe Ruth’s last three homers to the last tripleheader to all those triples. Wagner, Kiner and Clemente could all agree that excitement was never in short supply at the Old Lady of Schenley Park.

When one thinks about the steel-and-concrete ballpark era of the early 20th Century, the kneejerk vision is of a sturdy structure wedged into an urban street grid, surrounded by all the personality downtown had to offer. It’s a sound perception that most of the 14 major league ballparks built during this time answered to.

But not Forbes Field. The home of the Pittsburgh Pirates was not urban; it was urbane. Built away from the city, Forbes opened up and looked out toward a rolling green hillside dotted with oaks, prestigious learning centers and pricey homes. The view from the upper deck must have seemed like something out of Oz.

There was Schenley Road, wandering through the hills and crossing cobblestone bridges like the Yellow Brick Road. There was the Mary Schenley Memorial Fountain, shooting out water beyond the left-field wall as if waiting for the Good Witch of the North to come floating in via bubble. And there was the 42-story Cathedral of Learning towering high above the third-base side, looking so unreal that it might have been confused for a matte painting of the Emerald City. Pirates fans looked to their proverbial Toto and admitted, “I’ve a feeling we’re not in Pittsburgh anymore.”

On the field, there was always plenty of action to keep the fans’ eyes focused away from the dreamy landscape beyond. Forbes Field’s infield was as hard as rock—alabaster plaster, famed Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince frequently called it—and its unpredictable hops made cursing sailors out of choir boys whose jobs it was to get a glove on them. Tony Kubek didn’t get his chance to cuss on October 13, 1960; a hard hop shot up unexpectedly and nailed the New York Yankees shortstop in the throat, rendering him momentarily mute. It sparked a five-run, eighth-inning Pittsburgh rally in the seventh game of the World Series, just one of many memorable moments before the moment—when Bill Mazeroski ended the season on what many consider the most famous home run in baseball history.

Past the trampoline infield lay one of the most spacious outfields ever seen in modern times. In Forbes Field’s early years, a deadball had absolutely no chance to clear a wall that ran 360 and 376 feet down the lines (left and right, respectively) and 462 feet to the ballpark’s deepest point, just left of center. The entire outfield was triples alley; nobody proved that more than Owen “Chief” Wilson, who in 1912 established the Bob Beamon of baseball records when he collected 36 triples—24 of which were hit at Forbes—to set a mark that remains a whopping 10 above the next highest season total ever recorded.

Forbes Field, and all its memories, would simply not have been without the vision of a German immigrant who everyone thought was crazy to try and build such a gorgeous venue so far away from the heart of the city.

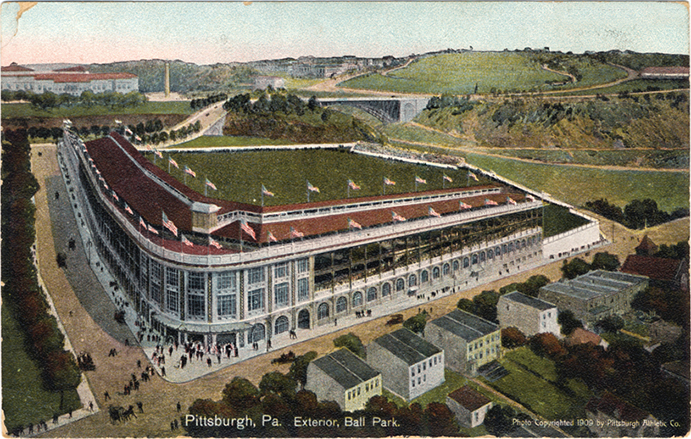

This postcard shows a rendition of the beautiful, pastoral environs beyond Forbes Field during the ballpark’s early years. (Detroit Public Library)

Carnegie Haul.

Barney Dreyfuss, a pint-sized, innocuous looking fellow, came to America all but penniless in 1885 to avoid serving in the German army. Fortunately, he had family in Louisville, and was put to work in a whiskey brewery where he shot up the ladder through hard work. So hard, his doctor told him to do something recreational to break the stress and avoid an early death. He chose baseball—not so much to play, but to run things. It perhaps provided no exercise for Dreyfuss but, instead, much-needed enjoyment. By 1889, he became an investor in the NL’s Louisville Colonels; 10 years later, he was running the whole franchise. But the NL wanted to contract from 12 teams to eight for 1900—with Louisville as one of the casualties. Dreyfuss stayed relevant by arranging a deal to become part-owner of the Pirates—and he brought his best Louisville players, including Honus Wagner, Fred Clarke, Deacon Phillippe and Tommy Leach, with him.

In Pittsburgh, Dreyfuss wasted little time assuming total control of the Bucs. Unfortunately, that also meant taking control of the Pirates’ ballyard, Exposition Park. It was a nice place as far as 19th-Century ballparks went, featuring medieval charm with twin spires flanking the front entrance. But while fire was the biggest threat to such wooden structures of the time, Exposition Park had the opposite problem: Water. It was built alongside the Allegheny River, which tended to overflow onto the field. And when it did, the show sometimes went on—with outfielders standing up to a foot deep and collecting any batted ball that floated their way, ruled as automatic singles.

Dreyfuss knew he had to find a better place to play than a flood zone within one of Pittsburgh’s more unfriendly neighborhoods. He began searching as early as 1903, and although it took him awhile he finally zeroed in on the Oakland area southeast of downtown, which was everything the land around Exposition Park wasn’t: Beautiful, upscale, cultural and free of floods. Oakland was the home of two universities, a top library, the luxurious Hotel Schenley, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, numerous museums and a symphony hall. But it was dominated by Schenley Park, a 300-acre expanse of mostly open space that had been bequeathed to Mary Schenley in 1850, who then mostly donated it to the City of Pittsburgh in 1889. She also gave some of the land to Andrew Carnegie, the Steel King of Pittsburgh—to say nothing of the world—who cashed out a few years earlier with a cool quarter-billion dollars and had become active in the philanthropy business.

With Carnegie’s help, Dreyfuss was able to secure seven acres on the park’s northwest edge—some three miles from downtown, a long way in 1909. The locals all shook their heads; Oakland might be beautiful, but it would be too far a jog for most fans. Dreyfuss wasn’t concerned; he correctly figured that the growth of the city would follow him—and furthermore, he wanted to build a ballpark in an area would female spectators would feel safe.

Dreyfuss wanted a ballpark that would be prestigious, even palatial, and fit in nicely within its surroundings. He found his man to design it in Charles Leavitt Jr., a landscape and urban architect/engineer whose portfolio would make him feel right at home in Oakland; he specialized in racing tracks—including New York’s Belmont Park, part of the triple crown circuit of horse racing—and in higher education, having developed the look for the Universities of Georgia and South Carolina.

Leavitt’s design for the Forbes Field exterior would be a rich mix of pleasant décor and color that would warm the hearts of even the chilliest passer-by. A cream-colored terra cotta was carved into repeating arches all along the street level, rising to the roofline only around the entrance with two levels of tall windows. Green steel embellishments complemented, most notably crosshatch patterns that rose between the arches and windows like supporting posts. Above the arches and to each side of the vertically extended entry façade, the interior was exposed with Pittsburgh’s finest steel and spectator ramps—a ballpark first—all topped by a copper roof.

Inside, Forbes Field initially would consist of a double-decked grandstand that extended just past each base, a common sight among the new steel-and-concrete ballparks of the time before expansionmania hit in the 1920s. There was a large, uncovered bleacher section down the left field line, and a smaller set of bleachers positioned behind the right field fence. But there was one wrinkle: A covered seating area above the roof, a primitive ancestor to today’s luxury suites which likely consisted of little more than a collection of folding chairs. Costing $1.25 per seat—the most expensive in the house when Forbes opened—the rooftop suites were accessed by elevator, another ballpark first.

Construction crews worked overtime and then some to build Forbes Field from scratch over a remarkably short four months. Making it easy was access to local steel mills; making it difficult was a 30-foot-deep ravine that cut through the future right field, as 60,000 cubic yards of dirt were needed to fill it in. Over in what would become left field, a small hill full of rock and stone had to be dynamited apart. Overall, it took an estimated 1,000 train cars’ worth of materials to build the ballpark.

Before its completion, Dreyfuss rebuffed calls from the locals to name the ballpark after himself and instead paid homage to John Forbes, a British general who fought both French troops and Native American tribes at the confluence of the area’s three rivers in 1758, and laid the seeds for what would become Pittsburgh—named by Forbes after then-British prime minister William Pitt.

As the Pirates readied to move from waterlogged Exposition Park, people couldn’t help but needle Dreyfuss about his new, suburban palace. They called it “Dreyfuss’ Folly,” something that could never be filled because of its relatively remote location. One friend even bet Dreyfuss a three-piece suit that he wouldn’t sell out the ballpark even once.

That friend would soon be taken to the cleaners.

The view from Schenley Park of Forbes Field during its very first game in 1909. (Library of Congress)

Opening on Top.

On June 30, 1909, Forbes Field opened for the masses as the Chicago Cubs came to town. The 25,000 seats, constituting the largest capacity within the majors at the moment, would quickly fill; overflow attendees, some sitting on a grassy warning track incline in left field, would bump the crowd to 30,388—topping the all-time mark for single-game attendance by just 141 over the Cubs’ regular season finale at Chicago just the year before. Pittsburgh mayor William Magee threw out the ceremonial first pitch; among the many other dignitaries present were Al Pratt, the Pirates’ very first manager from 1882, numerous team owners and both league presidents including NL head Harry Pulliam, one month before he committed suicide as ill health began to torture him.

The fans who watched the Pirates drop a 3-2 decision to the Cubs on Forbes’ first day clearly liked what they saw and experienced: The beautiful views, the spectator ramps, a field-level concourse spacious for its day and, perhaps just as importantly, the surprising ease of reaching the ballpark from downtown as trolleys strolled up to just a block shy of the front gates. Umpires liked it, too; it was the first ballpark to include a dressing room just for them. The critics were equally impressed, with the Reach Baseball Guide of 1910 stating: “For architectural beauty, imposing size, solid construction, and public comfort and convenience, it has not its superior in the world.”

Though Charles Leavitt Jr. called Forbes Field the “triumph” of his engineering career, he seemed to care more of caressing the structure to the outside street grid rather than to the playing field. Most modern ballparks follow the “V” shape for wrapping the field, but Forbes’ “V” was almost a condensed one—with the seats behind home plate pulled away from the action like a rubber band on a slingshot being stretched back. Forbes’ closest seats, and therefore arguably its best, were located near the first- and third-base bags while the expansive space behind home plate—a lengthy 110 feet to the backstop, easily the majors’ longest—led some to somewhat joke that the area required the catcher to occasionally become a fourth outfielder. Any wild pitch was sure to lead to at least a couple extra bases for baserunners. Each side of the grandstand was turned so inward toward the other that, when extra rows were added to the front of the section in the years to come, fans seated in the first row would literally have to turn and look over the heads of those in the two or three rows behind them to follow the path of any ball hit toward the foul pole.

Forbes Field’s inaugural campaign, although just half of one, would be a delightfully memorable one for Barney Dreyfuss and the Pirates. Fan enthusiasm for the new ballpark didn’t wane beyond its first date, with numerous more sellouts throughout the rest of 1909—and thus, more free suits piling up on Dreyfuss’ desk. The team, enriched with the star power of the legendary Honus Wagner, ace pitcher Vic Willis and manager-outfielder Fred Clarke—all Future Hall of Famers—won 37 of 53 games at Forbes, on their way to a franchise-record 110 victories and a thrilling seven-game World Series triumph over the Detroit Tigers and Ty Cobb.

The exterior of Forbes Field, shortly after its opening. Its charming façade helped redefine ballpark architecture in the infancy of the steel-and-concrete era. (Library of Congress)

It’s Yet Another Doozie Marooney.

The voluminous outfield at Forbes Field would be a prime source of pride for Dreyfuss. He abhorred the idea of “cheap” home runs and preferred that anyone willing to circle the bases would have to do it the hard way, with legs chugging hard to beat the throw from a distant outfielder. Often, they had to settle for three bases, which led to the preponderance of triples—or “doozie maroonies,” as early Pirates broadcaster Rosey Rowswell called extra-base hits.

Chief Wilson’s mind-bending 36 triples from 1912 is the one factoid that will always stick out the most in regards to three-bagger activity at Forbes, but there’s some other impressive feats that admirably take runner-up. In 1922, there were 142 total triples hit at Forbes between the Pirates (who had 79) and their opponents, the most ever at one ballpark over one season. Three years later, the Pirates collected seven triples on April 22 against the Cubs; five weeks later, they clipped that mark with eight—the most hit by one team in any game, ever—in the second game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals.

In the 60 full-time years in which the Bucs played at Forbes, they led the National League 29 times in triples; in fact, they hit more triples than home runs every year at Forbes until 1947, when they moved the fences in at left field. Even in the Pirates’ final half-year at Forbes in 1970—a time when homer-happy sluggers dominated, and with the fences long since moved back—the team was still managing to rack up more triples than quadruples.

In 1917, with the dead ball still quite dead, just six home runs were recorded at Forbes—and it’s likely many of those were of the inside-the-park variety. The Boston Bees’ Gene Moore, in 1936, became the first left-handed hitter to hit a ball the opposite way over Forbes’ left-field wall; not long afterward, he would become the second to do it. It wasn’t until 1962 that the San Francisco Giants’ Willie McCovey became the third. And nobody—left-handed or right—managed to poke one out over the ballpark’s deepest point in left-center, 457 feet away, until the Pirates’ Dick Stuart found enough strength to muscle it nearly 500 feet in that direction during a 1959 game, 50 years after the ballpark had opened.

The walls were so far back at Forbes, it was assumed that no outfielder would ever crash into one chasing a deep fly. So no one thought twice about placing objects in front of the walls, assuming they’d be little more than distantly safe, low-risk obstacles. These included the flag pole, located on the center field warning track, and the batting cage, at the 457 marker left of center. When lights were installed in 1940, three of the standards were planted into the ground in front of the outfield wall, from left to center—with cages placed around them to protect the players and, it would be assumed, the poles.

The instinct among pitchers was that Forbes, death upon power hitters with its spacious outfield, would make them dominant on the mound. But stunningly, no one ever threw a no-hitter at the ballpark—in fact, no one ever took one into the ninth inning. The closest anyone got was the Giants’ Carl Hubbell (in 1939) and the Pirates’ Bob Moose (in 1968), both of whom kept opponents hitless two outs into the eighth before conceding their first safety. The Pirates’ hitters themselves never felt that Forbes gave them a raw deal; they almost always hit better at home than on the road, and for nine straight seasons (from 1922-30) hit over .300 at the ballpark—topped by an impressive .338 figure in 1928.

Perhaps the two finest pitching performances at Forbes both occurred on the same day. The Pirates’ Babe Adams and Brooklyn’s Rube Marquard faced each other on July 17, 1914 and traded an early run, but then they gradually locked in and never gave, past the ninth, past the tenth, past the eleventh…all the way to the 21st inning. That’s when the Giants’ Larry Doyle stroked a two-out, two-run homer—inside the park, of course—to finally lay defeat on the Pirates. The game’s final out wasn’t without suspense; under darkening, threatening skies, New York outfielder Red Murray ran to make the final catch and, at that very moment, was knocked unconscious by a lightning bolt—and managed to still hold on to the ball. Murray wasn’t the only victim on the day; the exhausting workload upon Adams and Marquard—one has to wonder just how many pitches each threw on the day—would temporarily ruin them. Marquard would lose 11 straight games later in the season and be badly off his game for the next year or so to follow, while Adams, the rookie star of the Pirates’ 1909 World Series triumph, wouldn’t be the same for the next three seasons.

Adams’ frustration, short-term or otherwise, was the epitome of the Pirates’ fortunes (or lack thereof) during the 1910s at Forbes. The team stayed competitive early on but ran aground for the balance of the decade, as Honus Wagner hit 40 (as in years, not homers), Fred Clarke stepped down and, of course, the whole Adams breakdown. By 1917 the Pirates were 100-game losers, and increasingly fans decided it wasn’t worth it to ride the trolley three miles from downtown to watch a bad team in a beautiful part of town, with average game attendance buried in the 3,000s. For Barney Dreyfuss, this wasn’t the ideal way to settle into a nice new ballpark.

Fortunately, Dreyfuss made extra money on the side thanks to football. The University of Pittsburgh was a popular fall tenant early on at Forbes, and for good reason; behind legendary coach Pop Warner, the Panthers won national championships in 1915, 1916 and 1918. Two other schools, Carnegie Tech and Duquesne, also called Forbes their home; in 1933, a former minor leaguer named Art Rooney invested $2,500 for an expansion franchise in the fledgling National Football League. At first, Rooney also called his team the Pirates—but by 1940, they became better known as the Steelers and held hold autumn sway at Forbes Field through 1963.

A photo of a pick-up game during World War II shows the left field scoreboard and one of just two ads ever to be placed on Forbes Field’s outfield walls—this one exhorting fans to buy war bonds.

A Modest Shave Down the Right.

Baseball would return to the Forbes forefront in the 1920s thanks to the Pirates’ revival in the standings. In 1921, Pittsburgh moved back to serious contender status and then some, taking a 7.5-game lead into late August; Dreyfuss, seizing upon the thought of drawing much bigger crowds than the current structure could hold, quickly drew up plans to add 30 rows of bleacher seats behind left and center field to increase capacity by 10,000. But the Bucs lost 22 of their final 36 games while the Giants steamrolled right past them to the pennant; Dreyfuss’ bleacher dream would have to wait—but not that long.

Dreyfuss had always eyed an expansion of the grandstand to wrap around right field, but experts cautioned him that the ground on that part of the property—basically a landfill to smooth out the ravine that once cut through, pre-Forbes—might not be stable enough to hold a mass of steel and concrete. Yet Dreyfuss felt that 16 years of settled terra firma was enough to convince him that he could safely proceed with the addendum.

In 1925, the two main decks were extended with a pair of 40-degree turns, one cutting into right field and the other squaring up behind the existing outfield wall to right-center. The upper deck rose higher above the existing grandstand without the need for additional rooftop boxes, increasing overall capacity to over 40,000. The seamlessness of the interior would not be matched on the outside, as Charles Leavitt Jr.’s elegant façade was abruptly segued into a cold, industrial and more faceless exterior for the new sections, as if a factory had amalgamated with the ballpark.

The extension reduced the distance to the right-field pole to a mere 300 feet, but from there the wall angled quickly to the existing 376 marker at straightaway right. Any carom off that new wall section would redirect toward center, potentially meaning more work for center fielders already taxed with occupying all the space in their own territory. For left-handed, dead-pull sluggers, the closer reach provided with a chance to poke a routine fly past the right-field foul pole, a temporary boon that lasted seven years until 1932 when the Pirates erected a screen measuring anywhere from 14-to-18 feet above the wall from the pole to 376 in right. Although home runs rose at Forbes Field with the ballpark expansion—before and after the erection of the netting—twice as many triples were still being hit as the overall field dimensions remained quite spacious. Still, the ballpark became the unlikely scene of some of baseball’s greatest slugging feats.

On July 10, 1936, future Hall of Famer Chuck Klein belted three home runs for the Cubs in regulation, and then launched a fourth, the eventual game-winner, to lead off the 10th; two of his blasts landed atop the right-field roof. But Klein wasn’t at the tail end of his career with his impressive performance. Babe Ruth, on the other hand, was. A year earlier, an overweight, overaged and overdone Ruth, horribly flailing with the woeful Boston Braves, produced one last jolt—actually three—in a stunningly vintage effort. The 40-year-old Ruth crushed the final three homers of his career against the Pirates; the last one, #714, cleared Forbes’ right field roof, 86 feet above the field. Though no one broke out a tape measure to record the distance of Ruth’s last shot, it’s argued that the blast—easily over 500 feet—was the longest ever hit at Forbes. Giving him company were 15 other players who later reached or cleared the roof; Willie Stargell, playing through Forbes’ final nine seasons, did it five times.

The 1930s represented a time of change for the Pirates and Forbes Field. In 1930, Barney Dreyfuss, now 65, handed over ownership of the team to his son Sam. A year later, Sam died; a year after that, so did Barney. The burden of ownership fell upon Dreyfuss’ son-in-law William Benswanger, who thankfully would live into the Three Rivers Stadium era. In the first 10 years under his watch, Benswanger installed lights and loudspeakers, listed the dimensions on the outfield walls (at the request, it was said, of a fan), and made Forbes among the first ballparks to use padding on its walls—at least in right field, where the walls were concrete. Food stands were greatly approved under the watch of head concessioner Myron O’Brisky, who kept his job all the way to Forbes’ last game in 1970. A tireless man, O’Brisky once discovered that kids he’d hired to package peanuts had eaten some of them and placed the shells in the bags; to stop this, he offered them chewing gum because, as one quickly realizes, gum and peanuts don’t mix.

Finally, there was the curious case of Bruce McAllister, a man so loyally supportive of the Pirates that his wife felt she had become second fiddle in his life and divorced him. The Pirates had their own issue with McAllister, who frequented Forbes Field with ear-piercing bird calls that earned him the nickname “Screech Owl.” The Pirates thanked McAllister for his support by giving him a lifetime pass to Forbes—but only on the condition that he stop the screeching. McAllister took the pass—and kept screeching anyway.

Remaining competitive on the field throughout this time, the Pirates were making a hard run at the pennant in 1938 and Benswanger, like Dreyfuss before him, sniffed an opportunity to perform a quick upgrade, just in case the team made it to the World Series. During Pittsburgh’s last world title in 1925, an overflow of reporters forced the Pirates to relocate them behind home plate—and they were thoroughly drenched during a memorable (and very rainy) Game Seven. Hoping to avoid the same scenario, Benswanger took out the rooftop boxes from home to third base and built a makeshift annex of seats with a new press area. Aesthetics, once again, were not a consideration; from outside the main entrance, the new section appeared as an incongruous outgrowth upon the park’s original, more graceful facade. Adding injury to architectural insult, the Pirates once again blew a tire down the stretch after leading by seven games to start September—the seminal moment of their lost cause being the famous “Homer in the Gloamin’” by the Cubs’ Gabby Hartnett in Chicago to permanently knock Pittsburgh out of first place. The new press box, dubiously nicknamed the ‘Crow’s Nest’, sat unused as the World Series played elsewhere, and wouldn’t be occupied by any reporters until Forbes hosted the 1944 All-Star Game.

As good as the Pirates were during the 1930s, they may not have been the best baseball team calling Forbes Field home. The Homestead Grays were a Negro League outfit that put in uniform some of the greatest African-American ballplayers in segregationist times; among the names on the roster were Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson and Buck Leonard. The Pirates were fine with the Grays using the field, but they were to be hands off the clubhouses and showers. Those were for major leaguers (read: white) only.

During World War II and the days of nationwide rationing to aid the war effort, the only addition to Forbes Field came with the placement of a rare advertisement on the outfield wall. Barney Dreyfuss decreed from Day One that the walls would contain no ads so as not to spoil the beauty of the land beyond—but an exception was made when the Pirates placed a 32-foot tall wooden figure of a U.S. Marine against and above the left-field wall, telling fans to “Buy War Bonds and Stamps.” It wasn’t the first ad ever placed at Forbes Field; one war earlier, another ‘do your duty’ banner for Liberty Bonds had been posted on the wall during World War I. And lest anyone think that Forbes Field was totally free of corporate advertising, there were plugs for Studebaker Automobiles in the ballpark’s early years—one posted on the side of the uncovered bleachers down the left-field line, another in the form of 3D-lettering placed atop the back of those same bleachers for passers-by on the outside to read.

The deepest portion of the outfield wall is all that remains of Forbes Field in its original location. (iStock)

Reign of Sluggers.

After World War II, the Benswanger regime performed some long-overdue dolling up of Forbes Field, repainting the facility, renovating the bathrooms, adding a ritzy press lounge (called the Pirates Den) and borrowed from Chicago’s Wrigley Field by planting vines on the outfield wall. It turned out the team was trying to make the place more attractive for a potential buyer; within a year, it found one in a group of investors led by Indianapolis banker Frank McKinney, Ohio skyscraper builder John Galbreath, and actor-singer Bing Crosby. (Galbreath would emerge as the majority owner by 1950, remaining so through 1985.)

The new ownership didn’t think Benswanger had gone far enough and spent an additional $600,000—the only major flurry of upgrades Forbes Field would ever see. The dugouts, clubhouses and office spaces were refreshed; the concourse was updated with better lighting and 32 new concession stands; the entry-area elevator, once regarded as cutting-edge but now considered an obstacle because it hindered general fan flow, was removed. On the field, foul territory was reduced as 1,300 additional seats were placed around the infield, finally shaving 30 feet off the ridiculously long distance to the backstop.

But the talk of the town was centered around the Pirates’ plans for left field.

In 1946, muscular rookie Ralph Kiner matched his age with 23 home runs for Pittsburgh, good enough to lead the NL. But only eight of those cleared Forbes’ faraway walls. After the season, the Bucs were interested in acquiring veteran Detroit slugger Hank Greenberg, who won the American League home run crown with 44. Initially scared off by Forbes’ reputation as a graveyard for would-be homers, Greenberg declined the offer—even after Galbreath, a horse racing fanatic, had tempted him with a thoroughbred on top of a $100,000 salary. But then the Pirates began making noise about shortening the field distance in left, which would greatly benefit right-handed power sources like Greenberg and Kiner. After some reconsideration, Greenberg changed his mind and signed.

The installation of an eight-foot screen placed 30 feet in front of the existing wall in left would be a game-changer for Forbes’ baseball dynamic. That was clearly evident in the Pirates’ 1947 home opener against Cincinnati. In a 12-11 Pittsburgh victory, six homers were belted—five of them landing between the closed-in screen and the original wall, an area referred to as Greenburg Gardens that housed relocated bullpens for both the Pirates and visitors. The power display would become the new normal; in 1947, a Forbes Field-record 182 homers would be hit, with 116 of them landing in the Gardens. A fading, 36-year-old Greenberg hit 25 homers—18 at home—but the real star was Kiner, whose eye-popping 51 bombs included 28 at Forbes, many assumed to be deposited into the Gardens.

With Greenberg retired in 1948, Greenberg Gardens was rebranded as Kiner Korner, with the screen in left raised to 16 feet—an act that served as little more than a band-aid for the pitchers’ egos. Of the 33 instances in which a team hit four or more home runs in Forbes Field history, 23 of them took place in the seven years in which the Gardens/Korner existed. This included a Pirates-record seven jacks in a 1947 game, and a Forbes-record eight launched by the Milwaukee Braves in a 19-4 blowout of the Bucs in 1953. Roughly half of the home runs registered were said to be dropping into the Korner. Kiner certainly didn’t mind; for the six full seasons he played at Forbes with the shortened fences, he led or co-led the NL in homers every year, averaging 45 per season—27 of those at home. The Pirates certainly didn’t mind, either; the presence of Kiner and his Korner turned on the fan base, as attendance surged into seven-figure territory for the first time, topping out at 1.5 million in 1948—even as the team continued to stagger in the standings. In what would be a prelude to Mark McGwire half a century later, the large crowds at Forbes would rapidly thin out after Kiner’s last at-bat on the day, never mind the score.

In 1953, the power party ended. Kiner armwrestled a provision into his contract ensuring that the Pirates would not undo the Korner and return to the original wall distances. But the Bucs had descended into utter misery—they lost 112 games the year before—fans increasingly became spoiled by Kiner’s home run feats and stopped showing up, and before midseason he was traded to the Cubs. Branch Rickey, the legendary exec who joined the Pirates in 1951, famously told Kiner: “We finished last with you, and we’ll finish last without you.”

With Kiner’s departure, Rickey and the Pirates couldn’t get rid of the Korner fast enough. They tried the day after Kiner’s trade, but fellow NL owners told them they had to wait until after the season. No Pirate suffered more from the Korner’s eventual removal than Frank Thomas, another right-handed bopper who was Kiner’s heir apparent. In the five years after the Korner, Thomas belted 131 homers—with only 42 at Forbes. He even once had a home run robbed at Forbes by a layer of barbed wire, placed upon the top of the wall to deter fans from climbing over; the ball rebounded back onto the field, in play per the ground rules. By 1957, the Pirates as a team hit just 20 home runs at Forbes, the lowest total by any team at a home ballpark since the 1946 Brooklyn Dodgers.

Young University of Pittsburgh students with no fear of vertigo root the Pirates on during the 1960 World Series from atop the 42-story Cathedral of Learning, which towered above Forbes Field’s third-base side.

The Lame Duck Years.

Any chances that Forbes Field would be given further makeovers were greatly minimized in 1958 when the Pirates agreed to sell the ballpark for $2 million to the University of Pittsburgh, which had plans to tear down the joint for campus expansion. The school would patiently hold off on the bulldozers until the Pirates secured a new place to play, as the seeds of Three Rivers Stadium had already been planted—though it would take far longer for that project to come full flower than expected. There were a few minor updates in the meantime, including another 600 box seats added to the front of the field level and an expansion of the press box, but the most nostalgic addition was the placement of an 18.5-foot-tall, 1,800-pound sculpture of Pirates legend Honus Wagner behind the left field wall. Created by Frank Vittor, furiously lobbied for by past Pirates stars and costing $40,000, the sculpture was the first of a former player ever erected at a major league ballpark. The 81-year-old Wagner lived just long enough to see its introduction in 1955; he died six months later. (The statue currently stands at the front entrance of PNC Park.)

Forbes Field was given one last, magical jolt of life that famously peaked in 1960. Branch Rickey’s teardown and subsequent rebuilding of the Pirates had been initially considered a massive failure, but the more patient witnesses presaged better times—and they came starting in 1958, when the Bucs posted their first winning record in 10 seasons. Two years afterward, it all came together; the Pirates won their first pennant since 1927 behind the students of Rickey’s rebuilding class (Roberto Clemente, Bill Mazeroski, Bob Friend, Dick Groat), who were all maturing into pinnacle form. In the World Series against the almighty New York Yankees, the Pirates managed to maintain a pulse through to Game Seven at Forbes by winning three tight games (6-4, 3-2 and 5-2) while getting blown out in three losses (16-3, 10-0 and 12-0). In a crazy, back-and-forth affair with seemingly more twists and turns than the road to Hana, the Pirates got the last say in the bottom of the ninth when Mazeroski, whose primary strength was his smooth, quick fielding at second base, gained legendary status with one stroke of the bat—crushing a game-winning, walk-off-through-a-mass-of-delirious-fans home run over the ivied wall in left. Maz’s shot gave the Pirates their third (and last) world title at Forbes with a 10-9 win regarded by many as baseball’s greatest game.

The 1960 Pirates drew a record 1.7 million fans to Forbes, but the decade to follow showed a still-competitive team tolerating a decaying ballpark living on borrowed time as local politicians argued over the This and That of Three Rivers Stadium. Everyone tired of Forbes at in increased rate. It had the worst infield, the worst lighting (by a landslide, according to one survey), mass transit to the area had become antiquated while parking was a joke as the vernal tranquility of the surrounding area had increasingly been swallowed up by city outgrowth.

The fans were no less unruly—frankly, as they always had been; there was little mild-mannerisms to spare in describing a fan base that gave a hard time to the greatest of Pirates, from Honus Wagner to Ralph Kiner to Bob Friend—even Roberto Clemente, who hit .352 at Forbes from 1961 until the park’s closing, wasn’t spared from the wrath of the boobirds. The forbidding of beer brought into the ballpark starting in 1959—alcohol was never sold at Forbes—didn’t seem to help. According to The Sporting News, one Pirate told a visiting player in 1966: “Some of (the fans) are vultures. You have a bad night and they eat you up.”

The Pirates closed Forbes Field with a doubleheader sweep of the Cubs on July 28, 1970. Fittingly, Bill Mazeroski had the Pirates’ last hit—no, it wasn’t a walk-off—and made the last out at second base. Throughout the day, the Pirates officially raffled off many ballpark items, perhaps in an attempt to discourage youthful scavengers. It was a futile gesture; the fans went ahead with the ballpark’s deconstruction anyway, grabbing seats, clumps of turf and scoreboard panels. Someone even took off with the memorial to Barney Dreyfuss and his son that had been placed at the right-center field wall in 1934, shortly after their passing—but in perhaps an epiphany of remorse, it was returned to the Pirates a few days later.

Many bemoaned the closing of Forbes Field, but understood that its current condition just made continuing within it impossible. “There are thousands of people who will regret its passing; that’s human nature,” said William Benswanger in 1969. “I don’t know of a better playing field. But it can’t last forever.” Roberto Clemente offered, “I’d like to keep playing at Forbes Field. But you can’t stop progress.” Pirates pitcher Steve Blass was more embracing of the old yard and its spacious outfield: “I might arrange to have the new park flooded just to keep us at Forbes Field.”

The University of Pittsburgh didn’t get around to razing Forbes Field for another year after its final game, but a couple of crippling fires in between did its best to get the process started early. The site is now home to the school’s Wesley W. Posvar Hall, Hillman Library and Barco Law Building. Home plate is showcased under glass on a walkway floor inside Posvar Hall, said to signify its true former location—though opinions vary. Some say the actual location is in a nearby women’s restroom, while others say it’s just outside the building.

What does remain from Forbes Field is a portion of the wall, from its former deepest point of 457 feet near left-center to the 436-foot marker in center, along Roberto Clemente Drive. Every year on October 13, fans and former Pirates players congregate by the wall, celebrate the anniversary of Game Seven 1960 and listen to a radio replay of the game. Nearby, a plaque designates the spot where Mazeroski’s famed World Series home run landed. As for the slab of left-field wall that Maz’s historic shot sailed over, that’s been relocated along the Allegheny River next to PNC Park’s right field entrance, adjacent to a statue of Mazeroski recreating his jubilant home run trot against the Yankees.

Beyond these surviving reminders, Forbes Field remains only as a memory, but a strong and lasting one for those who followed the Pirates there for years. PNC Park strives to channel Forbes with its street-level arches, companion color scheme and its own breathtaking view (of downtown, as opposed to Forbes’ countryside), a definite enhancement in tribute over a sterile, enclosed Three Rivers Stadium that turned its back on Forbes’ legacy. But like Dorothy in Oz, the closing of the eyes and the click of the shoes will bring the elders who lived Forbes to revisit the old yard in spirit and declare, “There’s no place like home.”

The Ballparks: PNC Park If the Pittsburgh Pirates sense that they’re being ignored by their faithful at PNC Park, they shouldn’t take it personally; after all, the team’s only competition isn’t sitting in the visitors’ dugout. Spectators are easily distracted by mesmerizing views of downtown Pittsburgh, the Allegheny River and the Sixth Street Bridge, now named after Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. After thirty years of being locked in at Three Rivers Stadium, who can blame them?

The Ballparks: PNC Park If the Pittsburgh Pirates sense that they’re being ignored by their faithful at PNC Park, they shouldn’t take it personally; after all, the team’s only competition isn’t sitting in the visitors’ dugout. Spectators are easily distracted by mesmerizing views of downtown Pittsburgh, the Allegheny River and the Sixth Street Bridge, now named after Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. After thirty years of being locked in at Three Rivers Stadium, who can blame them?

Pittsburgh Pirates Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Pirates, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.