THE BALLPARKS

PNC Park

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

(Flickr—Dan Gaken)

If the Pittsburgh Pirates sense that they’re being ignored by their faithful at PNC Park, they shouldn’t take it personally; after all, the team’s only competition isn’t sitting in the visitors’ dugout. Spectators are easily distracted by mesmerizing views of downtown Pittsburgh, the Allegheny River and the Sixth Street Bridge, now named after Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. After thirty years of being locked in at Three Rivers Stadium, who can blame them?

“Picture postcards,” the iconoclastic American writer Henry Miller once wrote, “really excite me.” The millions of fans who’ve entered through the gates at PNC Park can relate. But for them, they’re not looking at a glossy 5×7. With a staggering view of downtown Pittsburgh connected by the Roberto Clemente Bridge over the Allegheny River, what fans behold is a postcard literally brought to life. It takes a long time for this view to get old—if, indeed, it ever does.

But the internal allure of PNC Park is just as stunning. Its inviting mix of ochre-colored limestone and naked navy blue steel, agreeable intimacy and plentiful nods to local baseball heritage makes the home of the Pittsburgh Pirates a one-of-a-kind achievement that’s simply impossible to criticize.

Look at any list of baseball’s best ballparks today and it’s a given that PNC Park will be near or at the top of the conversation. ESPN’s Jim Caple, hashing out a top-to-bottom ranking of major league facilities, summed up PNC Park in one word: “Perfect.” It received the only collective five-star rating from Yelp, the online user review site. And when smart-ass news site Deadspin focused on PNC Park for its “Why Your Stadium Sucks” series in 2009, it singled out the facility’s lone weakness: The Pirates themselves, who were mired deep in a record run of 20 straight losing seasons.

It’s easy to tolerate a loser when your ballpark is among the best, when it’s drenched in memories of better days on the field gone by. Just walk around the ballpark and you get the idea.

One who may not know Hank Aaron from Hank Azaria might take in the area around PNC Park and eventually ask, “Who is this Roberto Clemente and why do I keep seeing his name?” The legendary Pirate is everywhere. His name is on the bridge that connects PNC Park from downtown, a Pirate Gold-splashed span for which pedestrians get exclusive game-day access across the Allegheny. His statue, one of two holdovers from the gone-and-forgotten Three Rivers Stadium, welcomes fans coming off the bridge and through the Center Field Gate. Inside the ballpark, the right-field wall stands 21 feet high in honor of his uniform number and the position he played. And a long, nearby riverside park stretching nearly half a mile bares his name.

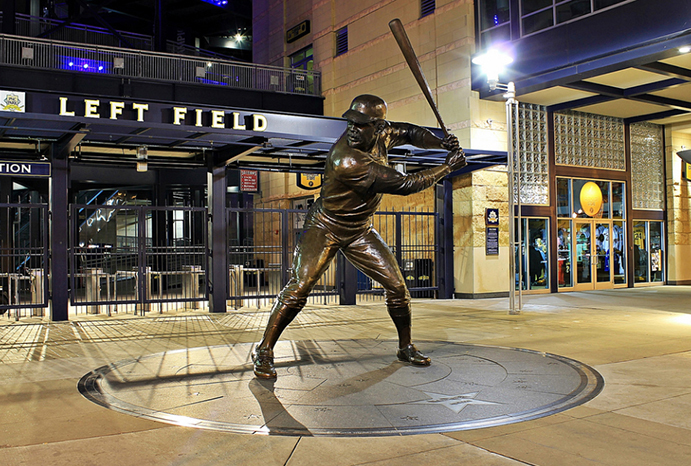

Clemente doesn’t hold the monopoly on PNC Park tributes to the past. Down Federal Street at the Left Field Gate sits the bronze reincarnation of popular Pirates legend Willie Stargell, which leads you to Pops’ Plaza—a food court named after him because it’s the kind of Good Eatin’ he would have loved: Barbecue, chicken sandwiches and crabfries. The Stargell statue begets a sad irony for Pirates fans; he died on the day PNC Park was born.

The other side of the ballpark takes you further back in time—way, way back in time, in the case of the Honus Wagner sculpture in front of the Home Plate Gate as a tribute to arguably the greatest Pirate of them all. From there, you can walk Mazeroski Way back toward the river, to the end of a cul-de-sac where you discover why the street is named as such: A towering statue of a celebrating Maz himself, recreating the frenzied trot he took around the bases after delivering championship glory with what often ranks as baseball’s most famous home run. Partially lining the end of the court is a replica of the brick red Forbes Field wall with the 406-foot marker that Mazeroski’s memorable 1960 shot cleared.

But it all comes back to that skyline, that picture postcard view. Fans sitting within PNC Park proudly absorb the view as a communal badge of honor, a base for an urban revival most locals are happy to experience—even if it came at a greater public cost then they desired.

Rust Belted.

A generation before PNC Park’s opening, Pittsburgh and its steel-based economy were stuck in reverse, rusting away as global competition closed one mill after another. As Billy Joel sang about nearby Allentown, the restlessness was handed down—and it was getting very hard to stay. When Mazeroski hit his legendary home run in 1960, Pittsburgh’s population was 600,000. Now, it was barely half that. Those who remained found work hard to come by, as reflected in the early 1980s when unemployment soared to 17%.

Inside the steely left-field corner rotunda, one of two at PNC Park. A saucer-like roof was originally planned at the top but was deemed too “futuristic.” (Flickr—oscarpetfan)

The Pirates’ state of affairs was no better. Just five years removed from a world title, the team had descended into a scandalous, drug-ridden mess; the arrival of gruff, straight-talking manager Jim Leyland cleaned things up and the Pirates found brief success from 1990-92 with the blessing of hot new talent in Andy Van Slyke, Bobby Bonilla and a prodigal legacy named Barry Bonds, but free agency eventually tore it all apart as the Pirates couldn’t afford retainment of their All-Star roster.

Being a small-market team was part of the problem—but an even bigger handicap was Three Rivers Stadium, a multi-purpose venue built in 1970 as a modern solution to rotting Forbes Field. Just 20 years after its opening, Three Rivers had become outdated, chastised and economic cyanide for a Pirates team poisoned under one of the worst stadium leases in pro sports. The Pirates’ ownership, a tenuous collection of private and public interests, was forced to absorb $60 million in red ink from 1986-94; things got so bad that the team had to go hunt for $8 million just to stay afloat in 1995. If intended as a subtle SOS to Pittsburgh, the plea for money would fall on deaf ears as the city itself was buried under nearly $30 million worth of debt. And so, the post-Bonds/Bonilla/Etcetera era of misery began—but even the most discouraging Pirates fan would never have imagined just had bad, and how long, the losing would be.

In 1996, Kevin McClatchy bought the Pirates. With old ownership ousted, the fear of the known had been eradicated. But now came the fear of the unknown: What would McClatchy, a life-long Californian barely in his 30s, do with the Pirates? Could he be a savior, or would he take them back to his hometown of Sacramento, a growing market already on par with that of Pittsburgh?

Relax, reassured McClatchy. He was not interested in pirating the Pirates away. But, he told local officials, you’ve got to help me get a new ballpark by 2001, or I will sell—with no guarantee of what the next buyer would do with the storied franchise.

Maybe Someday.

As early as 1991, the politicians were already on top of the idea of a sorely needed Three Rivers replacement when, almost out of the blue, Mayor Sophie Masloff publicly floated the idea. Just as quickly, a lukewarm response sank it; not enough money, it was said. But with the opening of Baltimore’s Camden Yards at Oriole Park 200 miles to the east, and Cleveland’s Jacobs Field 130 miles to the northwest, ballpark envy began to set in with Pittsburgh lawmakers and Masloff’s successor, Tom Murphy. To him, Jacobs Field was of particular interest, a parallel to what Pittsburgh yearned to be: A reborn, chic rust belt metropolis anchored by a beautiful and exciting new baseball-specific venue.

Murphy had to see Jacobs Field to believe it. And so, with local and state colleagues, he went on a field trip, sat in the bleachers of a full house and soaked in the potential. When asked by the press if the Jacobs Field visit was a sign of movement for a new Pittsburgh ballpark, Murphy played it cautious. “Maybe someday,” he said.

With McClatchy on board two years later, someday didn’t seem to be so far off. But the public had to buy into a new facility—figuratively, and literally. In 1997, with the cash-strapped Pirates down to a miniscule $9 million roster payroll, an initiative was placed on the ballot for voters in 10 counties, including Pittsburgh-based Allegheny County, to approve a half-cent sales tax increase to raise $700 million for a new Pirates ballpark, a new football stadium for the NFL’s Steelers and an upgrade to a convention center so out of date that it didn’t even have an ATM machine. Throughout the election season, McClatchy stayed not only in the shadows but also in the closet—admitting, 15 years later, that he had been gay all along and feared that any such public knowledge would enrage any homophobes among the electorate to vote no.

Gay, straight, whatever—it probably wouldn’t have mattered on Election Day. The ballpark-plus initiative was squashed by a 2-to-1 margin. With nearly two years of McClatchy’s five-year grace period already exhausted, Mayor Murphy and Co. quickly moved to Plan B. That’s what they actually called it: Plan B. The budget and the goals would be the same, but the funding mechanisms would be different—and more critically, the public wouldn’t have a direct say on it.

Allegheny County commissioners approved Plan B, but it needed additional help from the state of Pennsylvania to make it reality. Governor Tom Ridge, the future first head of U.S. Homeland Security, was more than happy to help, since a similar situation was brewing across the state in Philadelphia with the Phillies and football Eagles unhappy with the state of Veterans Stadium, another detested multi-purpose bowl the same age as that of Three Rivers Stadium. Ridge turned Plan B into a statewide bill to raise the debt ceiling by $650 million and secure a share of funding for four new sporting facilities in Pennsylvania, the Pirates’ ballpark included. It took a lot of arm-twisting and heartache—and two votes, after a first version of the bill grew toxic from lobbyist tinkering that enraged lawmakers—but in February 1999, it was finally approved.

The Willie Stargell statue, located behind the left-field gate. It was dedicated on April 7, 2001; two days later, PNC Park opened—and Stargell, struggling to recover from a stroke, died. (Flickr—Dave Reid)

Everyone would end up chipping in for the new ballpark. Pennsylvania residents from Erie to Upper Darby would contribute. Hotel guests in Pittsburgh would contribute. Fans would contribute through ticket surcharges. A Federal dose of $28 million meant every American would, essentially, chip in roughly a dime of his/her taxes to help get it built. Even visiting ballplayers would provide funds with a 1% “duty tax.” It goes something like this: Any major leaguer who played or practiced 250 days a year and visited Pittsburgh to play nine of those days would be taxed 1% on 9/250ths of his salary. Using that scenario, a $15 million-a-year player would be told by the taxman to contribute $5,400.

Yes, the Bucs would contribute some bucks of their own. They pledged $40 million, but most of that would be covered by a $30 million naming-rights deal with Pittsburgh-based PNC Bank. The pact was announced during a Pirates game at Three Rivers Stadium; those in attendance, wistfully hoping that the ballpark would be named after Roberto Clemente, responded with boos.

Set in Stone.

The Pirates were wasting no time visualizing PNC Park; a whole year before Plan B was approved, they already had Kansas City-based architect HOK Sport working on it. The hiring didn’t sit well with local architects who felt more inure to what the Steel City needed for a new ballpark, but it was hard to argue the choice given that Jacobs Field and Oriole Park at Camden Yards were recent additions to the HOK portfolio. Whether pressured or not, HOK subcontracted local firm L.D. Astorino to design the ballpark within the ‘big picture’ concept it already had developed.

Originally, that big picture was a venue built with red bricks, a default concept quickly drawn up just to show the public and politicians something in advance of the various ballpark votes. Once time became a luxury, lead HOK designer Dave Greusel decided one day to acclimate himself to Pittsburgh by taking a walk around town. What he saw would lay the visual foundation for PNC Park, as he attracted himself to the warm-toned stone that faced many of the city’s distinguished civic buildings. Sold on the stone, he went to make his case to the Pirates and was pleasantly surprised to find out that they, too, were thinking the same thing.

Thus, PNC Park would become the first major league park with a stone façade, built from ochre-colored Kasota limestone shipped in from Minnesota. The structure’s roughened base is fashioned into wide, inviting arches that breathe dimension and the occasional entry. Atop the base is smoother stone, rhythmically interrupted by thin horizontal strips of more jagged stone to give the facade a rustic, almost sub-Saharan feel.

PNC Park’s exterior consists of limestone both smooth and rugged, the latter variety lining the structure’s base and the horizontal strips above. (Flickr—Peter Bond)

But Pittsburgh was built on steel, and PNC Park wasn’t going to be constructed with stone alone. Along the exterior, navy blue steel does more than peak its way through the Kasota; it vertically slices through with stairways, peers over the top with an upper-deck concourse façade and breaks through at the park’s entry gates. Yet PNC Park’s true showtime elements of steel are its two rotundas, intentionally skeletal in scope and wrapped by an outer spiral walkway that feeds fans to and from their seats. One is prominently located behind the left-field foul pole and proudly shows off its alloy; the other, which welcomes fans behind home plate at the park’s main gate, is more hidden behind the stone—a request of the Pirates after the initial thought to expose the rotunda more openly to the outside looked too chasmal. That wasn’t all; both rotundas were originally drawn out with roofs later criticized as being too “futuristic.” HOK heard the commentary, said, “Okay, we get it,” and fixed things up.

The Pirates’ other directive to HOK was their desire to make the ballpark highly intimate, to keep even the furthest seats as close to the action as possible. Some considered this an ode to Forbes Field, but they forget that the first row at Forbes was once 120 feet behind home plate. At PNC, it’s a mere 51 feet. While that’s to be believed, the same cannot be said for the Pirates’ claim, on their own web site, that the furthest seat is only 88 feet from the playing field. Maybe 88 feet higher than the elevation of the field, yes—but the truth for the guy sitting in Row Y of the upper deck is that he’s actually more like 180 feet away from the action.

Excusing the exaggerations, PNC Park is intimate. It’s the first major league ballpark consisting of just two levels since Milwaukee’s County Stadium, built nearly half a century earlier. This was conveniently achieved by sliding the luxury suites under the upper deck, while morphing the middle “club” level seen at other new ballparks into the front of the upper deck, separated and sunken down a few feet from the cheaper seats above. The total capacity of PNC Park is just over 38,000, the second lowest in the majors; it’s a number arrived at not so much to heighten the intimacy factor but to also decrease supply and, therefore, increase the potential demand for tickets. Which works great, except when your team is losing year after year as the Pirates did for the first 13 seasons at the ballpark.

Staying Dry.

Being under the .500 mark is one thing; being underwater is something entirely different. The Pirates have been far more successful trying to avoid the latter. Aware that a swollen Allegheny River occasional wreaked havoc immediately around or even within two previous local ballparks—Three Rivers Stadium and Exposition Park (1891-1908)—the Pirates set out to make sure that PNC Park would always remain dry, even in the event of the biblical 500-year flood. Beyond the bank of the river, there’s the public walkway; beyond that, there’s a natural grass berm that slopes up some 10 feet; beyond that, there’s a second walkway covered by PNC Park limestone, opened by its signature arches and protected by an inner 10-foot wall that serves as the park’s last line of defense against invading floodwaters.

PNC Park has been carefully constructed so that potential floodwaters from the adjacent Allegheny River cannot spill over a series of defenses (as shown here beyond the riverwalk) and flood the field and lower seats. (iStock)

The expansive outfield concourse that stands atop the barrier wall is uncovered to maximize the glorious views of the Allegheny and downtown from most every seat in the house. The Pirates also chose to house their dugout on the third base side so the team would get the nicer view; one would have thought that it would have been wiser to instead plant the visiting team there, have them fall in love with the skyline and take their focus off the game at hand.

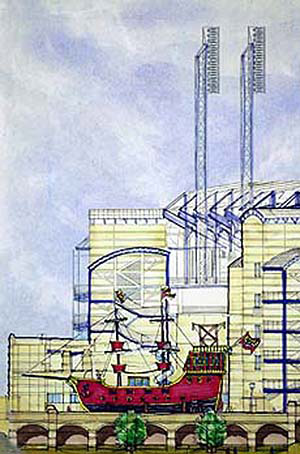

Other potential obstructions were also dealt with. None of the ballpark’s seven light towers, patterned after Forbes Field, were placed in center or right field so as not to block the view. The Pirates also had a vision, during construction, to use the open space to build a 70-foot long, 50-foot tall Pirate ship—much like the one built at the home of football’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers—and use it as a combo funhouse/baseball skills hangout for younger kids, with cannons to go “boom!” and scare the bejeezus out of the toddlers on board whenever a Pirates player went deep. Mutiny nearly ensued; the fans and media alike assailed the idea as too Disney-like. Tom Sokolowski, the director of the nearby Andy Warhol Museum, chipped in with his two cents and 15 minutes of fame by blasting the ship idea as a “cheesy fiberglass Good Ship Lollipop” that would “dumb down” the North Shore. Between the criticism and the lack of corporate funding, the Pirates mothballed the idea.

As with Oracle Park, home of the San Francisco Giants, PNC Park’s proximity and placement near water conjured up visions of players overshooting the right-field bleachers and reaching the Allegheny. But it’s a longer haul to the aqua than at Oracle; in fact, only twice has a player slammed one the minimum of 453 feet into the river, the first being Daryle Ward in 2002. Had the Pirates somehow held onto Barry Bonds all those years, he certainly would have been the first; when Bonds and the Giants first came to PNC in 2001, he belted six batting practice balls into the Allegheny on the fly. (In 42 real at-bats at PNC, the disputed home run king hit .429 with seven homers—all of them dry.) As it was, it took 13 years for anyone wearing a Pirates uniform (anyone, being Garrett Jones) to reach the river.

PNC Park has been carefully constructed so that potential floodwaters from the adjacent Allegheny River cannot spill over a series of defenses (as shown here beyond the riverwalk) and flood the field and lower seats.

With the skyline, river and Roberto Clemente Bridge providing a panoramic confluence of spectacle for PNC Park fans, it seemed almost inexplicable that Pittsburgh even considered other sites. But they did. Downtown locations were romanticized, but a viable pace of land was hard to come by. Outlying areas were dismissed as being too suburban. The floating ballpark concept, once idealized for Three Rivers Stadium, was once again floated but never set sail. The most serious discussion centered on the Strip District a half-mile east of downtown, where available land was aplenty and aging, elongated warehouses could provide a Camden Yards-like view. But the skyline won out. The North Shore location proved too clear a frontrunner.

Part of the lure of PNC Park’s ultimate location was that it could be accessed by any means. This has proven true, with the popular pregame exercise of fans walking from downtown across the Roberto Clemente Bridge, riverboat service ferrying folks from the far, Monongahela side of downtown and, starting in 2012, the long-awaited extension of light rail service across the Allegheny to the North Shore, with a stop between PNC Park and Heinz Field.

“You Were Right, We Were Wrong.”

As PNC Park gradually became reality and the locals began to get a strong sense that the venue was going to be something truly special, enthusiasm became unlimited. All 65 suites, some listed at three times the value of those at Three Rivers Stadium, were sold in six weeks—the fastest of any new ballpark to date. A franchise-record 17,000 season tickets were sold for the Pirates’ inaugural season at PNC Park, and 60,000 individual game tickets alone were sold on the first day they were available. One of the buyers who stood in line before sunrise had the last name of Yoho, as appropriate a name for Pirates fandom as Plank, Scallywag and Matey.

The rush for tickets led the Pirates to believe that PNC Park would follow in the footsteps of Jacobs Field, which had sold out game after game, year after year for the Cleveland Indians. Others weren’t so sure. “I don’t think they’ll pack the park,” said Pirates manager Gene Lamont as the team wound down their final season at Three Rivers Stadium. Lamont may have had an axe to grind; the Bucs had already informed him that his services wouldn’t be needed for their 2001 debut at PNC.

The crunch to build PNC Park successfully led to an accelerated construction schedule of 24 months; for one woman, that wasn’t fast enough. Weeks before the first official pitch, she somehow managed to drive her SUV onto the field and went for a spin, thankfully doing more damage to the warning track than the grass. She was arrested not only for trespassing but for driving with a blood alcohol content level of 0.20, twice the legal limit.

The more patient fans who legally filed into PNC Park for two sold out exhibitions fell immediately in love with the setting, the intimacy and of course the views; those in attendance who had voted against the ballpark were converted into apologists. They walked up to embattled mayor Tom Murphy and told him, “You were right, I was wrong.” One fan told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “I challenge anyone who was a naysayer to come here and see a game.”

The Pirates’ players thought a lot of their new digs as well, but worried that the panoramic eye candy would take the fans’ focus off the game. “The place has too many views,” lamented Pirates pitcher Terry Mulholland to the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Nobody’s watching us play. They’re all looking at the buildings, looking at the bridge, looking at the river, looking at other parts of the stadium. I don’t think anybody here even knows who’s on our team.”

For those who do focus on the action, they watch a ballyard that by and large favors the pitcher. If you’re a left-handed power hitter who pulls the ball, you’ll be fine; it measures 320 feet down the right-field line and 375 to the nearby gap. If you’re a right-handed slugger who favors the gap, you won’t be fine—unless you like a lot of doubles and the occasional triple. That’s because PNC Park registers 383 feet to the left-field gap and gets even deeper toward center, with a nook in left-center measuring 410 feet away from home.

And whereas Forbes Field had Greenberg’s Gardens, PNC Park has the Greenberg Wall, the backstop named after Pirates vice president Steve Greenberg—who thought it would be fun to drive catchers insane by placing the jagged brand of Kasota limestone behind home plate, forcing wild pitches to carom in unpredictable directions. (Greenberg, in case you’re wondering, is no relation to Hall-of-Fame slugger Hank Greenberg—for whom Greenberg’s Gardens were named after.)

The 21-foot, Roberto Clemente number-sized wall in right is home to perhaps the most detailed out-of-town scoreboard you’ll find anywhere in the majors. It doesn’t just show you the current score and inning of other games, it gives you the number of outs and number of men on base via a diamond graphic cornered by lights. Given its complexity, it’s hard to imagine that the scoreboard is manually operated by some guy in a booth, lest he be going delirious trying to keep up with the real-time progress of as many as 14 games at once.

The Buc Flops Here.

PNC Park might have been beautiful and new, but the Pirates who occupied it were nothing more than the same ol’ Bad News Bucs, losing the official home opener to Cincinnati, 8-2. The Reds’ Sean Casey, a Pittsburgh native who had a thing for famous firsts and lasts (he had the last hit at Milwaukee’s County Stadium and the first at its replacement, Miller Park), took things a step and many feet further when he drilled a home run for the first hit at PNC Park; never before had someone gone deep for a major league ballpark’s first knock. The ball was caught by a custodian working for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and he was willing to give the ball back to Casey—for $5,000. Grudgingly, Casey said no thanks. The ball was eventually auctioned off for $9,400.

PNC Park is deserving of a full house at almost every game, but the Pirates made sellouts a challenge by posting losing records in each of their first 12 seasons at the ballpark. This 2008 game drew an “announced” crowd of 10,487. (Flickr—Nicole)

As the inaugural season started, Pirates manager Lloyd McClendon believed the dark days were over and that PNC Park, with all its instant popularity and revenue potential, would thrust the Bucs out of their financial straitjacket and render its small-market stigma as irrelevant. “We’ll never be in a position again where we lose our free agents because of economic reasons,” McClendon told the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. “We’ll see free agents knock on our door here instead of us begging them to come.”

McClendon’s analysis hit a stone wall of major league reality. PNC Park was a crucial improvement on Three Rivers Stadium in terms of aesthetics and the bottom line, but it didn’t allow the Pirates to leapfrog ahead of the other franchises, many of whom had already built or were building their own new modern palaces. In a sense, PNC Park was more about maintaining survival, not creating success, for the Pirates.

The Pirates lost 100 games in 2001, including 43 at PNC, but still drew a franchise-record 2.464 million fans. By the time they finally established a winning home record—43-38, in 2006—attendance had whittled back toward 1.5 million, a figure that recalled the team’s latter, depressing days at Three Rivers Stadium. By then, Kevin McClatchy—who failed to fulfill his promise of winning baseball, hand in hand with a new ballpark—gave up and sold. The new owner, Bob Nutting, continued the losing tradition. The low point at PNC came early in 2010 when, with the Bucs on their way to a 57-105 campaign, they were swept by the Milwaukee Brewers by a composite score of 36-1, capped on Cap Day with a 20-0 slaughter that was the worst defeat in 125 years of Pirates baseball.

Finally, in 2013, the Pirates turned things around, registering their first winning record in 20 years. Fans gradually began returning to PNC Park—still hailed as one of baseball’s best parks over a decade after its opening—and the venue received some long-overdue national exposure when it hosted a game on ESPN’s venerable Sunday Night Baseball in 2014. The lesson was learned. Aesthetics don’t get you on national TV. Winning does.

A Slow-track Growth.

As beautiful as PNC Park looks, it has undergone its fair share of fine-tuning. An upscale beer garden, an increasing must in all ballparks, has been wedged into the corner behind the right-field corner. Nearby, an all-you-can-eat section in the bleachers allows you to pig out on unlimited hotdogs, nachos, ice cream, soda and other basic guilty pleasures for a price. Over behind the left-field bleachers, an Outback Steakhouse that debuted with the park and was open year-round has been replaced by the Rivertowne Brewing Hall of Fame Club—which includes indoor and outdoor dining and is one of the few spots within that allows alcohol service after the seventh inning.

A real Hall of Fame of sorts—one devoted to the Pirates and their history—was constantly talked about during PNC Park’s infant years but has yet to come to fruition; its lack of progress may be due to a tug-of-war that took place between the Pirates and the Allegheny Club over who owns a cache of artifacts that the latter group was said to have possession of.

It took a while, but development around PNC Park has finally taken root, allaying the fears of those who felt that a lack of growth would mirror the failure of Three Rivers Stadium to do likewise. A long talked-about amphitheater between PNC and Heinz Field finally got built in 2010. Two hotels owned by Marriott are situated on the north side of PNC Park, right across the street. There is a healthy abundance of imbibing establishments around the ballpark, from McFadden’s Saloon on the west side to the Beer Market on the east. The future still beckons; plans are in the works for a corporate development north of the park, with hi-rises towering above the third-base side of the park. It might remind older Pirates fans of the Cathedral of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh, which loomed mightily over Forbes Field.

Across the Allegheny, PNC Park has helped make it hip to be downtown. When the ballpark opened, there were 1,900 residential units in downtown; now, there are roughly four times as many. Commercial real estate has been just as vibrant, lured by the presence of the ballpark. One architectural firm with an excellent view of PNC from its 17th-floor offices joked—maybe—that they would have to paint the windows black to keep from being distracted.

The very best view of PNC Park action from the outside can be had if you ask for a room at the Renaissance Hotel, which sits at the southern base of the Roberto Clemente Bridge in downtown. Ask for a room that ends with “08”; the higher up the floors you go, the less obstructed your view of the game will be of the infield, exposed between the right- and left-field bleachers. It doesn’t come cheap; rooms at the Renaissance start around $300 a night.

It’s hard to imagine that PNC Park will ever be replaced; of course, people thought the same way about Three Rivers Stadium when it opened. But nobody fell in love with Three Rivers. PNC is strong and attractive enough to earn a ticket for the long run, to possibly be revered a hundred years just as Wrigley Field and Fenway Park, the classics many ballpark critics compare it to, have managed to do. The postcard-like pictures taken every night by the thousands at PNC Park are each worth a thousand words. And this ballpark is work a million praises.

The Ballparks: Forbes Field Removed from downtown Pittsburgh’s choking smoke and untamed rivers, elegant Forbes Field was built in a vernal, cultural paradise on the outskirts of town, where three was the magic number—from three Pirates world titles to Babe Ruth’s last three homers to the last tripleheader to all those triples. Wagner, Kiner and Clemente could all agree that excitement was never in short supply at the Old Lady of Schenley Park.

The Ballparks: Forbes Field Removed from downtown Pittsburgh’s choking smoke and untamed rivers, elegant Forbes Field was built in a vernal, cultural paradise on the outskirts of town, where three was the magic number—from three Pirates world titles to Babe Ruth’s last three homers to the last tripleheader to all those triples. Wagner, Kiner and Clemente could all agree that excitement was never in short supply at the Old Lady of Schenley Park.

Pittsburgh Pirates Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Pirates, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.