THE BALLPARKS

Qualcomm Stadium

San Diego, California

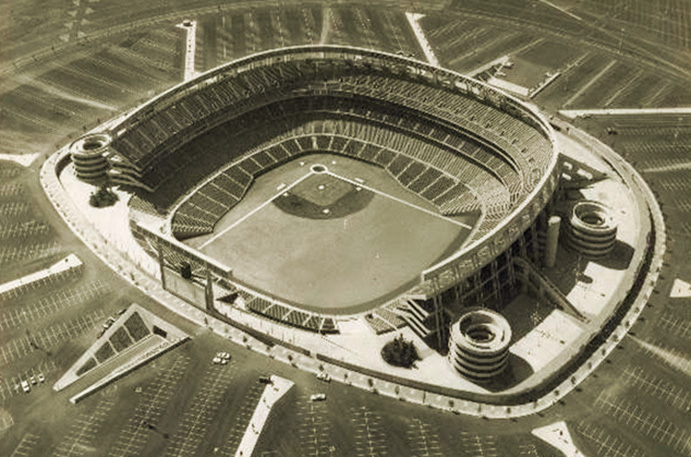

Buffeted by giant corkscrew-style ramps and surrounded by a sea of parking, Qualcomm Stadium—originally named after the beautiful city that built it, followed by the fellow who championed it into being—could have been confused for a modern-day fortress, especially in a town renowned for its military reputation. Yet for nearly 50 years it shined as the beacon that lifted San Diego into the major leagues.

There was a time when San Diego yearned to be the new kid on the block. That time was during the postwar baby boom years when West Coast cities began growing by leaps and bounds. San Diego was no different, attempting to transcend its image as a military town and become a significant business and sports player. When its populace eagerly approved and built San Diego Stadium—later Jack Murphy Stadium, later Qualcomm Stadium—in the late 1960s, it reached that goal; pro sports arrived in earnest, and without it the major league version of the San Diego Padres surely never would have existed.

Qualcomm Stadium was perfectly established within the once pristine Mission Valley, a gateway of sorts for eastbound travelers facing a rugged desert landscape; it’s also equally accessed with ease from downtown and the outlying suburbs thanks to two major interstate freeways crossing one another to the south and east.

Aesthetically, Qualcomm Stadium is pleasing and somewhat relaxed, like a beach chair nearly cranked up to full sit-up position. But there’s hardly anything provocative or memorable about it; there’s no signature element that distinguishes it from baseball’s more famous plants past or present. No city views, no green monsters, no pools. They tried ivy once on the outfield wall, but no one seemed to notice—or care. The place is more pragmatic than quixotic, more functional than wow. When people go to Boston, they have to see Fenway Park; when they visit Chicago, a pilgrimage to Wrigley Field is a must. For tourists preparing to invade San Diego, Qualcomm lists way low on the priority list in Fodor’s—with sun, sand and animal parks residing as sightseeing kings.

And yet for Padres fans who watched their team at Qualcomm for 36 years—37, if you count the minor league Padres’ use of the sparkling new venue in 1968—there was nothing to really hate about the “Murph,” except for the occasional expansion that gave it more of a football feel and eventually forced the team to look towards downtown and Petco Park.

Growing Up.

Downtown is where it all started for organized baseball in San Diego when the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League relocated and, with the help of WPA funds, got Lane Field quickly built for the 1936 season. It was a basic wooden structure located at the west end of downtown, on the waterfront a few blocks north of where the mothballed U.S.S. Midway hangs out today, and it welcomed the rechristened Padres and their youngest lad, a 17-year-old local kid with big dreams of becoming a major league star. At that point, few people had heard of Ted Williams. That would change very quickly within a few years.

Williams would outgrow Lane Field and then outlast it. The wood was losing the war against the marine air and termites, sending the Padres in search of a new home; they found it in the agricultural oasis of Mission Valley, some five miles north of downtown. Westgate Park, a beautiful 8,000-seat facility complete with grandstand roof, modern angled lightstands and an outfield grass berm for family picnicking, was built in 1958 at a point halfway between the coast and the future site of Qualcomm Stadium. Valley farmers and other residents at first protested the idea, worrying that it would accelerate development; someone should have sent them the memo that, sooner more than later, mushrooming city growth was headed their way whether they liked it or not. The Padres themselves initially hesitated on whether to build, unsure of the PCL’s future with San Francisco and Los Angeles in the midst of being granted major league citizenship.

As expansion fever hit the pro sports world early in the 1960s, chatter intensified as to whether San Diego would catch it. Plans were put into place of expanding Westgate Park to as much as 40,000 in order to welcome a major league transplant; the Milwaukee Braves, Kansas City Athletics and Cleveland Indians were among those rumored to be looking. But football had also become a player with the Los Angeles Chargers of the fledgling American Football League moving in; the city thus began looking at the idea of a multi-purpose joint.

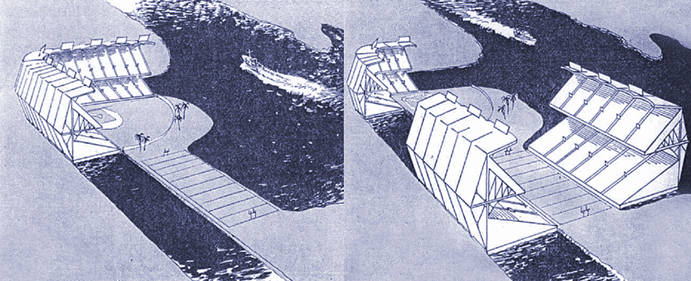

Before building the new stadium in Mission Valley, the City of San Diego seriously considered a “floating stadium” concept in Mission Bay in which grandstands would be moved into place for either baseball (left) or football (right). The idea was ultimately deemed too expensive. (San Diego Union)

Among the voices lobbying for a big-time stadium was San Diego Union sportswriter Jack Murphy, who had seen promise in San Diego since arriving in town a decade earlier. Murphy used his pen to publicly push for Westgate Park, and not only did he suggest the Chargers’ move to San Diego, he was directly active in the effort. He had to start lobbying again when the Chargers, well supported in San Diego but grumbling about playing at ancient Balboa Stadium, threatened a move to Anaheim if they didn’t get a better place to play locally. A move to an expanded Westgate Park wasn’t going to work because it was too baseball-centric.

Murphy must have written columns the way Henry V rallied troops at Agincourt. An enthusiastic voting bloc approved the stadium project with ease in November 1965 by a 72% landslide. It may not have ensured a major league franchise for San Diego—baseball in the mid-1960s was hemming and hawing over if and when it would next expand—but it certainly put the city at the front of the line among likely candidates.

To Float or Not to Float.

By Election Day, the city had already decided to build the new stadium in Mission Valley. The site wasn’t its first choice; Mission Bay was. It’s not what you’re probably thinking; the thought was not to build a stadium alongside the bay, but on it. The ‘floating stadium’ idea went like this; two fields, one each for baseball and football, would be laid out alongside each other on land sticking out into the bay; for baseball, a permanent grandstand would be joined by two double-deck structures from each side that would float into place. Those structures would then float to each side of the football field for use there. Jack Murphy did his usual best to sell the floating stadium to the public, calling it “the most daring, yet practical concept in stadium building since Houston discovered the dome.” Turned out it would also be expensive, at over $40 million—almost double what a conventional stadium on land would budget. There was additional fear, in the wake of chilly Candlestick Park’s opening up in San Francisco, that the proposed waterworld might be too cold for San Diegans—never mind that San Diego’s summer fog is far more pleasant than San Francisco’s arctic pea soup.

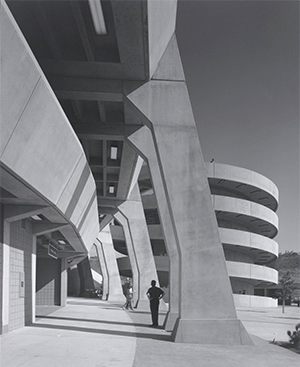

When veteran local architect Frank L. Hope won the job to design San Diego Stadium, he asked the creative young minds working under him if they wanted to take the lead on the project. Only one raised his hands. Gary Allen already knew what he had in mind for the stadium, and it was something novel for the time; instead of absorbing and hiding the inlets and outlets as older ballparks and stadia did, he would have them proudly exposed on the outside, as much an architectural statement as it would be to provide laid-back relief within the stadium structure. Symmetrically spaced around the horseshoe-shaped stadium would be six massive spiral ramps that coiled from the spacious ground entry plaza to the upper deck; in between them would be diagonal escalators and cylindrical elevator shafts.

Once inside the stadium, one could still feel a kinship to the outside. On paper, San Diego Stadium may have felt voluminous with its three decks, but its single-decked opening to the east gave a relaxed feeling of openness. Giant light towers would not spoil the view; there were none. Allen ingeniously imbedded all the lighting within a slim “light ring” that arced the upper deck, seamlessly topping vertical concrete supports that leaned inward from their bases at plaza level and framed the entire structure, intentionally exposing the various concourses to the usually agreeable outside elements rather than wall them off.

Allen’s final touch was his choice of seat colors, a wild palette which included purple, orange, blue, magenta, yellow and, of course, “bilious chartreuse.” The reactions were just as wide-ranging and colorful, with many seriously wondering if Allen was under the influence of LSD. He wouldn’t have been the last; Pittsburgh’s Dock Ellis threw a 1970 no-hitter at San Diego Stadium and later famously claimed he did so while under the drug’s influence.

The slightly angled concrete supports in the foreground, a corkscrew spectator ramp in the background: San Diego Stadium shortly after its opening in 1968, as photographed by noted architectural photographer Julius Schulman.

Surrounding the stadium, then as now, is parking. Acres and acres of it. It’s so vast an area, stadium officials initially scrawled out a race track on it and, under the name of the San Diego Stadium International Raceway, held an auto racing event there in 1968; few people showed up to watch and the neighbors complained about the noise. Some ambitious fans have attempted to bring San Diego flavor to the parking lot by trucking in beach sand to play volleyball as part of a tailgating ritual. That’s no longer allowed in the Qualcomm Stadium parking lot bylaws.

Thanks for Voting Yes—Now if You Would Just Show Up…

San Diego Stadium opened in 1967 with an exhibition football game between the Chargers and the Detroit Lions. The following April, baseball debuted at the facility when 18,000 showed up for a preseason affair between the Giants and Indians. The PCL Padres followed by playing their entire 1968 schedule at the 50,000-seat stadium and drew a total of 200,000—curiously, a 20% drop from their final season at Westgate Park.

Meanwhile, baseball decided it was time to expand once again. Considered a frontrunner to land one of two new franchises, San Diego instead found itself fighting for its major league life when National League owners met on May 27, 1968. Throughout a long, arduous day, it appeared that Montreal and Buffalo would be the winners, but intense lobbying from West Coast owners Walter O’Malley (Los Angeles) and Horace Stoneham (San Francisco)—desperate for a new team closer to home to cut down on travel expenses—knocked out Buffalo and secured San Diego as the second expansion team on the 18th ballot.

So many people had supported the new stadium, but when the major league Padres began play in 1969, it was asked: Where did all those folks go? The Padres’ debut at San Diego Stadium drew just 23,370; the next two games drew gatherings of 4,218 and 4,922. Only twice for the rest of the year did the Padres top 20,000; when the Giants’ Willie Mays came to town and smashed his 600th career homer late in September, only 4,779 showed up to see it—and memorabilia hunters were absent in the empty left-field bleachers where Mays’ ball bounced about.

Although the new stadium was praised—it even won an award from the American Institute of Architects—the new baseball team that called it home was a disaster. Over the first five years of their existence, the Padres lost an average of 100 games and placed dead last in NL attendance every season. Padres minority owner Buzzie Bavasi, well aware of the city’s love for golf, tennis, boating and surfing, could only shrug his shoulders at the weak gate and admitted to Sport Magazine, “How can you compete against the good life?”

Not helping to attract fans to the park was an absolutely anemic offense. This was an offense that averaged less than three runs a game in its inaugural season. An offense that once had to pinch-hit for a pitcher throwing a no-hitter (Clay Kirby) after eight innings because they were trailing, 1-0. An offense that included Enzo Hernandez, who in 1971 collected only 12 extra base-hits and 12 RBIs in 549 at-bats. An offense that got no-hit by a pitcher (Dock Ellis) totally doped out on acid. It would have been far worse for the Padres were it not for sideburned slugger Nate Colbert, who hit more home runs at San Diego/Jack Murphy/Qualcomm in a Padres uniform than anyone else with 72—and who, in 1972, knocked in a major league-record 25% of his team’s runs.

There was no doubt that San Diego Stadium was initially a pitcher’s park. The symmetrical dimensions—330 down the lines, 375 to the power alleys and 420 to straightaway center—didn’t sound too daunting, but they were flanked by a 17-foot wall that added more difficulty for the hitters. By 1982 the Padres placed a shorter (eight feet) fence in front of the wall that encourage more sock, but they didn’t move the foul poles with it; they remained two feet behind the new fence, making it possible for a drive down the line to actually cross the fence fair but curve just to the foul side of the pole.

By the end of 1973, San Diego’s major league experiment appeared doomed to failure. The team was headed nowhere in the standings and on its way to Washington D.C. as owner C. Arnholt Smith—so instrumental in San Diego baseball since buying the minor league Padres in 1955—ran out of cash and into trouble when his bank failed amid criminally bad loans that would land him in prison. When it appeared that San Diego Stadium would be without a baseball tenant—Topps had already began printing 1974 baseball cards with Padres players identified as “Washington, National League”—McDonalds founder Ray Kroc agreed to a stroke-before-midnight purchase of the team, keeping them at San Diego Stadium.

Qualcomm Stadium after its first expansion; the middle deck and suite section have been extended toward the bleachers, where additional seats have also been added. The view of the nearby hills has been retained—for the moment. (Jerry Reuss)

The Murph Comes Alive.

The Kroc regime re-energized the franchise and the fans responded to its passion, most memorably recalled on Opening Night 1974 when, in the midst of a horrible display by the Padres, Kroc himself grabbed the public address mike and verbally chastised the team in front of 40,000 fans. Kroc eventually apologized, but he had nothing to be sorry about when, in the middle of the year, his team introduced a guy in a chicken suit who apparently had won over the kids when he first dressed up for an Easter egg event at the San Diego Zoo. The man in the suit was Ted Giannoulas, and the character he played was the San Diego Chicken; with quick-thinking wit and a smart-ass attitude that was family friendly, the Chicken became an instant hit with the fans, ignited the modern sports mascot movement and helped pushed Padres attendance over a million for the first time. After all, the Padres themselves couldn’t possibly have been responsible for the spike at the turnstiles; they lost another 100 games.

When Giannoulas was fired amid a contract dispute in 1979, his replacement was booed; all was forgiven after he won a lawsuit and got back in the suit, becoming a national phenomenon so big that he appeared at other sports venues around the country and even got his own baseball card.

The 1980s brought the first cosmetic changes to the stadium. First, it was renamed, and appropriately so, in honor of Jack Murphy after his passing in 1980. The stadium was also given its first and only sculpture: One of Murphy and his dog Abe. From this point on, Jack Murphy Stadium would be lovingly referred to as The Murph, and many long-time sports fans of the city still prefer it over the current corporate name.

When the Padres finally made their first postseason appearance in 1984—shocking the Chicago Cubs after falling behind two games to none in the NLCS—The Murph had just completed its first expansion, adding 10,000 seats by extending the two lower decks and placing additional bleacher seats behind the existing ones; more importantly, 50 suites were added. The expansion was certainly agreeable with the Chargers, who had outgrown the original 50,000-seat capacity, and it didn’t seem to bother the Padres—this time.

If there was anything “iconic” about Qualcomm Stadium, it would be the four corkscrew ramps that fortressed the structure. Here’s a good look at one as seen at night. (Flickr—Deejay)

The 1990s brought turbulent times for the Padres and their relationship with the Murph. Hollywood producer Tom Werner bought the team in 1990 and immediately rubbed fans the wrong way by bringing in actress-comedienne Roseanne Barr—whose hit TV show Werner had produced—and having her trash her way through a rendition of the Star Spangled Banner a la Edith Bunker. When the fans booed, she responded by grabbing her crotch and spitting. A few years later, Werner began a roster purge of fire-sale proportions that so angered Padres fans that some season ticket holders at the Murph sued. He also tarped the upper deck to keep ticket demand for the lower two bowls at a premium, but there wasn’t much of it given the Padres’ lousy performances under his rule.

Werner gave up in 1994 and sold the Padres to software bigwig John Moores, who quickly stabilized the franchise and within a few short years had it back in the postseason—and two years after that, to the World Series for the second time in franchise history. One Padre was there for both: Tony Gwynn, the fan favorite, Hall of Famer and eight-time batting champion. In his 20 years playing at the Murph, Gwynn hit .343, ramping it up to .462 for the Padres’ two Fall Classic appearances—but they only won one of nine games (home and away) because they had the misfortune of timing their appearances alongside two of baseball’s greatest teams: The 1984 Detroit Tigers (who bolted to a 35-5 start) and 1998 New York Yankees (114-48).

Other players racked up some big-time numbers at the Murph. Unfortunately, not many of them played for their team. In the stadium’s early years, no one pitched better than Tom Seaver—though few pitched better at any ballpark of the time. But he was particularly death on the Padres, winning 18 of 23 decisions with a nasty 1.58 ERA. On the offensive side, the latter years were dominated among the visitors by—surprise, surprise—Barry Bonds. The steroid-fueled San Francisco superstar matched Gwynn’s .343 average but with far more power, blasting out 39 home runs in 105 career games at the Murph.

After a second expansion in 1997 turned Qualcomm Stadium into a football-oriented monstrosity, the Padres began looking elsewhere for a new ballpark. (Jerry Reuss)

Strangers in Their Own Home.

In 1997, a second expansion all but enclosed the Murph, transformed it into a football-oriented monster and relegated the Padres to second-class citizens within their own facility when the city gave the Chargers full financial control of the 113 suites. (The Chargers also got a bizarre—and very unpopular—sweetheart deal in which the city would pay for any unsold football tickets up to 60,000 per game.) To help pay off the cost of the extra suites, 10,000 additional seats and four new semi-circular lounges that morphed out of the existing structure—all needed to appease the Chargers and up their shot at hosting a future Super Bowl—the city changed the name of the venue again, this time to Qualcomm Stadium. Fans protested, but hey—Qualcomm had the $18 million kicking around to buy the naming rights. The Jack Murphy estate didn’t.

With the retro ballpark movement in full swing elsewhere, the Padres knew that Qualcomm Stadium was no longer in their long-term interests. They had enough of football’s omnipresence, enough of September grass chewed up on a weekly basis by the Chargers and the San Diego State Aztecs, enough of drawing a solid crowd of 35,000 only to see just as many empty seats staring them in the face. And so the Padres immediately went to bat on working with the city to build a new baseball-specific park, and late in 1998—fueled by the team’s NL pennant-winning campaign—the voters said yes to a new downtown ballpark that would eventually go by the name of Petco Park.

The Padres played for the final time at Qualcomm on September 28, 2003, losing to the Colorado Rockies, 10-8—their 1,401st loss at the stadium as opposed to 1,366 wins. Not everyone on the field was happy; San Diego manager Bruce Bochy was ejected in the seventh, and Rockies slugger Todd Helton was intentionally walked in his last at-bat by Padres reliever Rod Beck when a hit would have won him the NL batting title. A crowd of 60,000—5,000 shy of the all-time baseball record established during the 1998 World Series—trudged to watch this great game at Qualcomm one last time.

Is the End Nigh?

After the Padres’ departure, Qualcomm endured numerous deathwatches as it neared its 50th anniversary. The Chargers looked to follow the Padres’ path and build a downtown stadium, but voters this time said no. The Bolts bolted, and quickly—fleeing to Los Angeles where they’d patiently await a new facility they would share with the Rams, who also returned to town. Meanwhile, back at Qualcomm, the cracks and rebar began to show, and people complained that the place increasingly reeked of urine and beer. Finally, Qualcomm had something in common with Ebbets Field.

Qualcomm Stadium as seen from its vast parking lot on the outside. The upper concrete rim houses all of the venue’s lighting. (iStock)

So time has run out on Qualcomm, but only as everyone has known it. San Diego State, the stadium’s remaining tenant, has taken command and will remake the venue as a 35,000-seat facility which will also involve mixed-use development and park space.

Qualcomm showed that San Diego belonged on the pro sports map. It hosted two World Series, three Super Bowls, multiple college bowl games (including the semi-prestigious Holiday Bowl, which in 1984 determined a national champion in BYU), international soccer matches, Billy Graham, numerous big-time concerts and even drag racing in its parking lot. Twice, the stadium served as a relief center for those fleeing massive wildfires in the San Diego area.

It will probably never happen, but it would be a cool gesture for the Padres to pay their respects to the place that launched them into major league reality and play one last time at Qualcomm—or SDCCU Stadium as it’s now known. It would be a worthy tribute to an unassuming but critically important structure.

The Ballparks: Petco Park The city gave the Padres a Quarter, and the Padres gave back something priceless. Petco Park is the perfect ballpark for the perfect climate, a verdant place where laid-back San Diegans can break out the picnic blanket, unfold the beach chair or grab a stool atop a historic landmark before taking a leisurely stroll to adjacent streets lined with gaslamps, restaurants and bars to wash away the latest 1-0 result.

The Ballparks: Petco Park The city gave the Padres a Quarter, and the Padres gave back something priceless. Petco Park is the perfect ballpark for the perfect climate, a verdant place where laid-back San Diegans can break out the picnic blanket, unfold the beach chair or grab a stool atop a historic landmark before taking a leisurely stroll to adjacent streets lined with gaslamps, restaurants and bars to wash away the latest 1-0 result.

San Diego Padres Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Padres, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.