The Ballparks

Shibe Park

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

In baseball’s landscape of horse buggies and wooden carts, Shibe Park emerged as the Model T of ballparks, a sparkling trendsetter that introduced steel and concrete to the game’s vernacular, beget rooftop entrepreneurs long before Wrigley and brought the game out of its lumbered, fire-cursed squalor. That it stood for generations while two tenants largely stank up the joint was a testament to its perseverance.

The game of baseball, through the first 30 years of its professional existence, had undergone an aggressive evolution with rules that finally settled in for the long run after the Turn of the Century. But the maturation of the ballparks in which the game was played dragged along at a much slower rate. Yes, they gradually grew bigger, but structurally and aesthetically there was neutral advancement. Elegance, on occasion, would rear its pretty head at the front entrance, such as the classy medieval spires at Boston’s South End Grounds or the Romanesque Palace of the Fans in Cincinnati. But for the most part, major league venues were essentially no different from what they had been decades earlier: Physically basic, architecturally uninspiring and, as purely built with wood, prone to a five-alarm blaze at any moment.

Shibe Park provided baseball with its long overdue great leap forward. The first folks to stumble upon its magnificent, opulent façade could not have imagined that a ballfield hid behind it. This place, a ballpark? Perhaps an opera house or five-star hotel, but not a ballpark.

Constructed with cutting-edge steel-and-concrete techniques, Shibe Park would become, along with the future openings of the Houston Astrodome and Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards, one of the seminal turning points in ballpark history. It sprang a revolution that resulted in a turnover of nearly all major league ballparks over the next 15 years and put an end to the fading debate over whether baseball had graduated to modern times.

Over its long life, Shibe Park would be home to two of baseball’s greatest and most fleeting dynasties, a jaw-dropping pennant race collapse, and an awful lot of awful baseball. The fans were often far from civilized—this is Philadelphia, after all—but through thick and (mostly) thin, they got a kick out of the place.

Growing Up Fast.

Like most other American League teams that began operation in 1901, the Philadelphia Athletics hastily built their first facility using lots of wood but little imagination. Columbia Park was propped up on the cheap ($7,500 by most estimates) and sat 9,500 people willing to show up; they did, and in much bigger numbers than the A’s anticipated, as sellouts and overflow crowds became the norm. The team’s performance had much to do with it, constantly winning and exuding personality from brilliant oddball ace Rube Waddell to half-Native American Chief Bender to Ivy League-schooled Eddie Collins to the man leading it all, the tall, lean Connie Mack—always donned in suit, tie and derby while using his rolled-up program to waive the players into position from the bench.

The growing pains underscored the need for a bigger ballpark. Mack and Ben Shibe, the local sporting goods mogul who doubled as the A’s principal owner, began looking in earnest for a spot to build. They found it on Lehigh Avenue, some three miles north of downtown on the fringe of the countryside—a transitional mix of farms, factories, fens and homes. While it seemed anything but centrally located, Mack and Shibe liked the area’s growth potential, with likely expansion of tract housing, trolley service on Lehigh and train stops within walking distance. They quietly bought out the land, parcel by parcel, under assumed names so as not to tempt landowners into jacking up the price. The city also gave Mack and Shibe assurance that an unwanted neighbor—the Philadelphia Hospital for Contagious Diseases—would be closed down and relocated. (It would, two months after the ballpark’s opening.)

To build their new steel-and-concrete palace, the A’s called upon the aptly named William Steele & Sons, a prominent architect and contractor whose other historical claim to fame would be the 11-story Witherspoon Building, Philadelphia’s first skyscraper. That building’s dignified arches, firm use of brick and flourishes of fine decorative detail provided a sneak peak of what lay ahead at Shibe Park.

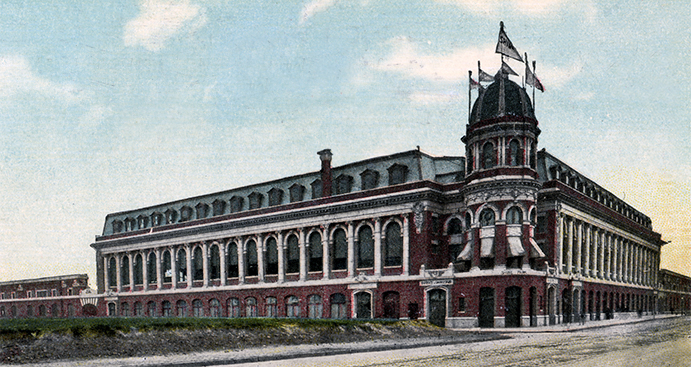

A hand-colored postcard shows the external opulence of Shibe Park in its original look, shortly after its 1909 opening. (The Rucker Archive)

The French Connection.

There would be a distinctive French appeal to the exterior of the A’s new building. The primary structure consisted of a red brick façade handsomely offset by a series of arches—semi-arched windows and doorways at street level, topped by a second story of taller, open-air arches separated by off-white Ionic posts. At top was an industrial lime-colored, French-style Mansard roof dotted with dormer windows, protruding outward and horizontally aligned with the arches below.

Adding opulent charm to Shibe Park’s façade would be a series of garish embellishments, most distinctly a pair of terra cotta reliefs extending from the brick wall—one in honor of Shibe, the owner, and the other for Mack, the former catcher-turned-prime mover of the franchise.

Comfortably nestled within the structure at the corner of Lehigh and 21st, behind home plate, was Shibe Park’s piece de resistance: The French Renaissance-inspired tower, with a cupola dome rising above the grandstand roof, ringed at top by eight small flags. Here, the A’s front offices would be located—with the top story reserved for Mack, a spot he would hold for the next 45 years.

At the tower’s ground level, fans would walk through a 24-foot-wide rotunda and into concourses measuring 14 feet in width to reach their seats. Internally, the 20,000-seat ballpark lacked the aesthetic splendor of the outer façade, featuring a no-frills, double-decked grandstand stretching from first to third base while roofless bench seating extended down each line to the foul poles. To make use of the space under the stands, auto garages were set up for fans and players lucky enough to own a car at the time—and also to house Ben Shibe’s impressive collection of motor boats. (There was also said to be some streetside retail shops under the stands as well, indicating a method of mixed-use occupancy that major league teams wouldn’t tap into for almost another 100 years.)

Construction lasted almost exactly one year, a timeframe perhaps helped by the innovation of a little something created by William Steele & Sons: A cement mixer. By April 12, 1909, Shibe Park was officially christened as baseball’s first steel-and-concrete Mecca, beating Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field by a few months. And it seemed that everyone in Philadelphia was there to enjoy the moment.

Shibe Salad Days.

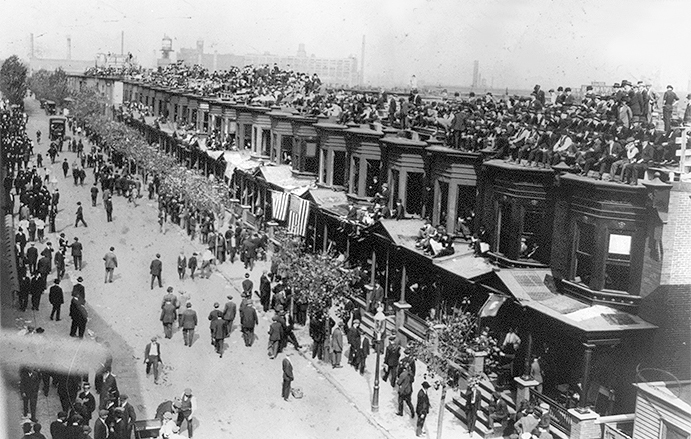

Lines of potential ticket-buying fans grew longer and more tense as game time neared; the A’s obliged by admitting 10,000 overflows, most of them stationed behind ropes in an outfield with plenty of real estate—Shibe opened with dimensions 360 feet down each line and a staggering 515 feet to straightaway center. All available vantage points of the action from inside or outside the ballpark were taken; fans sat atop the tall concrete outfield walls and atop the rooftops and porch lids on houses lining Somerset Street behind left field and 20th Street behind right, igniting a tradition of elevated knothole fandom well before homes surrounding Chicago’s Wrigley Field made such viewing iconic.

Not everyone may have been prepared for the steel-and-concrete era. During the A’s inaugural 8-1 win at Shibe over the Boston Red Sox, catcher Doc Powers—an original Athletic from their first season in 1901—reportedly ran smack into the concrete wall chasing a pop-up and, after the game, fell ill with intestinal pains. Two weeks later, he was dead, having lost a persistent battle with what doctors described as “gangrene of the bowel.” Though some say a pregame sandwich may have been the actual culprit, others say the collision with the wall may have fatally disrupted his innards.

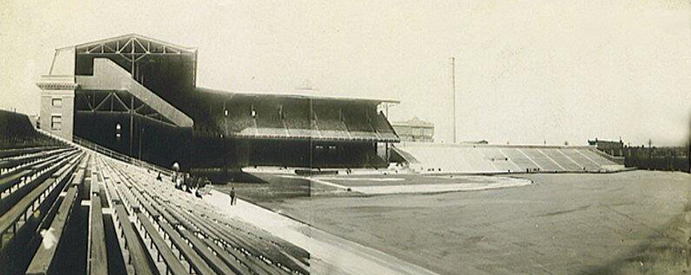

When it opened, Shibe Park included a double-decked grandstand from first to third with extended, uncovered bleacher seating down the lines.

Ballpark security, in the form of Philadelphia’s finest, crossed its fingers that Ty Cobb wouldn’t become a second casualty at Shibe Park in its first season. The legendary and immensely volatile Detroit superstar had created a firestorm of controversy midway through the 1909 season when, during a visit to Shibe, he laid down a nasty slide, spikes up, on popular Philadelphia third baseman Frank “Home Run” Baker that infuriated the A’s and their fans. When the Tigers returned to Shibe for a four-game series in September, police seriously took the threat that someone might open fire on Cobb from one of the houses behind the outfield wall. For a brief moment, the worst fears appeared to come true when a loud popping noise was heard outside the ballpark, causing Cobb to flinch in the outfield; it turned out to be a backfiring car.

Shibe Park’s initial five years coincided with Connie Mack’s first dynasty. Already a solid organization with two AL pennants and a lone losing campaign through its first decade, the A’s elevated their game to more stratospheric heights with four more pennants—including their first three world titles.

Not surprisingly, it was tough to find a weakness within this powerhouse of a team. Speedy, slick-hitting Eddie Collins led a talented group of infielders named the “$100,000 Infield,” underscoring its unparalleled value and the fact that $100,000 went a long way back in the day. The pitching was par excellence, peaking in 1910 when brief wonder Jack Coombs (31-9, 1.30 earned run average) fronted a staff that produced an AL-record 1.79 team ERA. And Home Run Baker was nicknamed for what he did better than anyone else at the time, becoming the first player to go deep at Shibe Park (in its 10th game, on May 28, 1909) before pacing the league in homers each season from 1911-14.

Some immediate upgrades took place in 1913 when the single-decked stands down the lines were given a roof, while bleachers were put in left field—ruining the views of Somerset Street residents who could no longer watch games for free. Meanwhile, their counterparts on 20th Street, still unobstructed, evolved their methods of making money on game days to cottage industry levels. They removed their windows, set up seating within the house and atop the roof, and concocted food and drinks for patrons with hefty markups after buying the goods downstairs from street vendors. Barkers were even employed outside the front door to woo people in, the way they might for a burlesque show.

By the late 1910s, getting anyone interested to see the A’s inside or outside of Shibe Park proved the ultimate challenge. Maintaining a talented, veteran roster combined with competition from a third circuit (the short-lived Federal League) resulted in a large salary bubble for Mack. So he popped it, crashing the dynasty. Overnight, the A’s discarded their star players and went from perennial contenders to laughingstocks. After winning the pennant in 1914, the A’s lost 109 games in 1915—and finished an all-time AL-worst 36-117 in 1916. Seasonal attendance plummeted from a then-respectable 600,000 to as low as 150,000. As few as 23 fans showed up for one 1916 contest. Mack desperately threw anything against the wall to see if anything stuck and, usually, it didn’t. Certainly not when pitcher Bruno Haas endured a harrowing major league baptism by fire in 1915, forced to go the distance in the second game of a doubleheader at Shibe in which he walked an all-time record 16 opponents and surrendered 15 runs—seven unearned, thanks in part to four errors by another brief blunder, third baseman Owen Conway.

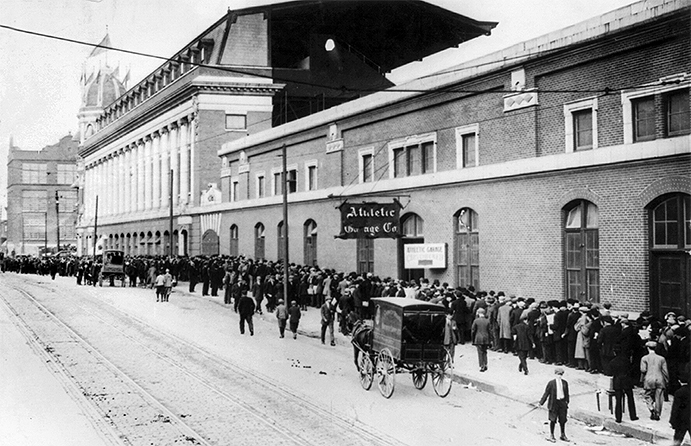

Fans line up to enter Shibe Park before a game in 1911. At center is the entrance to the “Athletic Garage” where the few players and fans who owned cars at the time could park them under the stands. (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

A Visual Disharmony.

The recovery from the post-dynasty depression would last a decade. Then Mack, who apparently had saved up enough money from paying no one over the previous 10 years—and by now enjoying majority control over the team after the passing of Ben Shibe in 1922—started spending again, both on talent and the ballpark.

The 1925 expansion to 33,000 seats—and a 1929 update to the original grandstand, adding a press box and mezzanine—overwhelmed and tarnished the exquisite beauty of the original structure. All existing single-decked sections were given a second level with roofing, but the exteriors for all upgrades were cast in a droll white facing, bereft of any ornamentation or class; the result was a clash with Shibe’s initial aesthetic. Further exacerbating the rhythm was the construction of a tall, horizontally thin elevator shaft that rose high to the right of the front entrance tower; it only needed to be painted black to look as if the spooky monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey was keeping tabs on Mack’s office.

Mack felt he would need the extra seats to accommodate an increased fan base ready to embrace his new wave of talent. Every year during the 1920s, it seemed, he brought along a future Hall of Famer into the ranks. There was perennial batting title contender Al Simmons, hard-nosed catcher Mickey Cochrane, nine-time ERA champ Lefty Grove, and muscular slugger Jimmie Foxx. These players constituted the core of Mack’s second dynasty, one that starting in 1925 would reel off eight straight winning records and, from 1929-31, three straight pennants—the first two of which would result in world titles. And they would all dominate unlike few others in Shibe’s history. Simmons’ .368 batting average (on exactly 1,000 hits) would top the all-time ballpark charts, as would Foxx’ 181 home runs; and while Grove’s 120 wins would be surpassed only by Robin Roberts (at 126), he lost only 32 games—64 fewer than the future Phillies ace.

Shibe Park in 1930, showing off the double-decked expansion of seats down the lines and behind left field. The ordinary white exterior of the expansion provides a visual conflict with the grace of the original structure.

We’re Going to Have a Live Ball.

Dynasty II did bring out the fans, with yearly attendance peaking over the 800,000 mark. The increased capacity also reduced field dimensions, particularly down the lines and into the gaps; so long as one didn’t hit it to dead center (still a distant 468 feet away), Shibe would favor the hitter. Combined with the American League’s live-ball environment of the 1920s, 1930s and sometimes beyond, it made the ballpark a scene of explosive offense on more than a few occasions.

In 1925, the A’s and their opponents combined to hit .300 at Shibe. That same year, the A’s notched at least 10 runs in five straight games—the first of which featured a 13-run rally in the eighth inning that wiped out a 15-4 Cleveland lead. A statistically less impressive but far more famous outburst came four years later in Game Four of the 1929 World Series, where the A’s entered the seventh inning trailing the Chicago Cubs, 8-0—and exited it with a 10-8 lead, setting a still-existing Fall Classic record for runs in an inning.

Opponents had fun, too. The New York Yankees’ Lou Gehrig smoked four home runs in a 1932 game at Shibe; Pat Seerey matched that in 1948 for the Chicago White Sox, albeit in extra innings. Boston’s Jim Tabor went deep four times during a 1939 doubleheader that included a major league-record 54 runs scored on the day between the Red Sox and A’s. The Yankees’ Tony Lazzeri—batting eighth in the order—knocked in 11 runs during a 1936 contest won by New York, 25-2. The A’s George Caster once left a start in 1940 after conceding six home runs to the Red Sox—in just 2.1 innings of work.

The history of any ballpark from the steel-and-concrete era wouldn’t be complete without at least one Babe Ruth story. Although Richie Allen’s 529-foot blast in 1965 is officially the longest in Shibe Park annals, Ruth unofficially topped that in 1930 when a titanic smash dwarfed the right-field wall, cleared 20th Street, the houses on it, the houses behind those and the small alley-like street they fronted (Opal Street) before making contact with a window on the far side of the alley. Estimated distance: At least 550 feet. It’s possible, though, that Ted Williams had Ruth beat—even if his prodigious foul blast, which was said to land a full three blocks past Shibe’s right-field reach on 19th Street, didn’t count. If witnesses to the event were to be believed, then Williams’ ball traveled roughly 700 feet on the fly.

Shibe Park was not an automatic stat padder for every legend. Mel Ott, the great New York Giant who reigned as the National League’s all-time home run leader until Willie Mays and Hank Aaron caught up decades later, did just fine when he visited Philadelphia and took on the Phillies at Baker Bowl—smashing 40 homers in 119 career games. But when the Phillies moved to Shibe starting in 1938, Ott simply couldn’t figure the new place out; in the 71 games he logged there, he never once went deep.

A look down 20th Street and the fans piled up atop homes behind the right field wall during the 1914 World Series. A tripling of the wall’s height in 1935 would put an end to the practice. (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Mr. Mack, Tear Down This Wall!

Slowly, but just as surely, Connie Mack dismantled his second dynasty in the mid-1930s. This time, he had the Great Depression to blame—as did most everyone in baseball at this point—but he also claimed the A’s became so dominant a team that the fans began taking it for granted; attendance, Mack theorized, would be more optimal if the A’s fought to the wire to win the pennant. But as with the deconstruction of his first dynasty, Mack went too far in ripping apart the second. Thus the talent-drained A’s initiated another long malaise of bad baseball, annually toying with 100 losses. And the fans? They didn’t care to see a dogfight for last place, either. Attendance sank once more.

Wary of reduced revenue, the A’s feverishly began to fight for every last dollar to bring people into Shibe Park. They received one gift in 1933 when Sunday baseball was finally allowed in Pennsylvania. Then, in 1935, the team put an end to the 20th Street freeloaders, nearly tripling the height of the right field wall to 34 feet to block their view of the games. The kneejerk reaction of the residents was to simply build higher bleachers, but the city—in legal cahoots with the A’s—told them they couldn’t. So they next sued, somehow ready to argue their right to make money on someone else’s product without permission. They were laughed out of court.

Players were no less happy about the heightened wall. Left-handed sluggers had their home run output curtailed, and the make-up of the fence—sheets of corrugated metal held together by an exposed latticework of vertical iron posts and horizontal crossbeams—created unpredictable caroms that drove outfielders nuts.

The extended right field wall would be something of a blessing for 20th Street residents in 1939 when Shibe Park became the first AL park outfitted with lights, resulting in higher turnouts for night games. The wall blocked most of the brilliant nighttime illumination from the homes, but night still tended to become day in many rooms; homeowners returned to court in an effort to stop it, but lost again.

For Rent.

The A’s soon would benefit from several new tenants. Midway through the 1938 season, the Phillies fled the badly deteriorating Baker Bowl just a half-mile to the east and begin play at Shibe because, why have one bad team at the local ballpark when you can have two? The Phillies were just as moribund as the A’s, and eternally so; they had no recent dynasties to brag about. Things would only get worse in the Phillies’ first years at Shibe, as the team suffered through a merry-go-round of inept owners, a half-hearted, unsuccessful name change (the Blue Jays) and astoundingly bad play. As bad as the A’s had become by 1940, the Phillies were worse—and it was reflected at the gate as well as the standings.

Football was also invited into Shibe Park starting in 1940 as the NFL’s Eagles set up camp for the next 18 years. Square in shape, Shibe was one of the easier steel-and-concrete era ballparks to transition to football; the field ran end zone to end zone from the first-base line to the left-field wall, and the extra room in right field was filled in with temporary bleachers, resulting in good sightlines throughout the venue. Unlike their baseball counterparts, the Eagles performed well at Shibe—winning back-to-back NFL titles in 1948-49, the first of which was a memorable 7-0 feat of survival over the Chicago Cardinals played in a snowstorm.

The presence of three teams and baseball’s postwar attendance boom prompted the A’s, by 1948, to look into putting more permanent seats in right field. The plan was to enclose the existing double-decked structure, with the upper level sticking out 15 feet over the 20th Street sidewalk, a la Detroit’s Tiger Stadium. The residents on 20th, already inflamed by the tall wall and the lights, tried once more in court to stop it. This time, they won—and Shibe Park’s capacity stayed at 33,000 for the long haul.

Near Shibe Park’s main entrance was an elaborate relief dedicated to long-time Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack; it includes a catcher’s mask, a nod to Mack’s playing career behind the plate. (Library of Congress)

The kids—alright, so they were in their 50s—made some dignified gestures to honor their father by renaming the ballpark Connie Mack Stadium and opening up an on-site museum of sorts under the grandstand called the Elephant Room, but overall they didn’t know how to run a business. The A’s fell heavily into debt and, worse, Earle and Roy feuded first with estranged family members and then with each other.

With the Phillies’ front office now stabilized under the Carpenter family and the team occasionally winning—it ended a 35-year pennant drought thanks to 1950’s “Whiz Kids”—the A’s had firmly devolved into the second banana of Philadelphia baseball; by 1954, rumors were rampant of a move out of town. The Macks did, in fact, want to sell, and tried hard to secure local ownership to keep the team in Philadelphia. But they were crushed when AL owners soured on the local buyers and forced the Macks to sell instead to Arnold Johnson, who would move the team to Kansas City. The A’s, on their way to Missouri as well as their 11th 100-loss season in 46 years at Shibe, played their final game at the ballpark on September 19, 1954; not even the almighty Yankees could churn out enough nostalgic fans to bid Auld Lang Syne to the A’s, as a meager turnout of 1,715 watched the home team lose one last time, 4-2. Less than a year and a half later, Connie Mack would be gone, too, passed on at the age of 93.

It’s All Yours Now—Good Luck.

The Phillies, which had bought Connie Mack Stadium from the A’s in 1954 for $1.7 million, began to spruce up the park as the sole baseball tenant. A fresh new field was planted, the seats were repainted in Phillies Red, billboards were placed on the outfield walls and atop the left field bleachers for the first time, and a towering new scoreboard was erected in right-center that mimicked the one at Yankee Stadium. (In fact, some today buy the urban legend that the Phillies purchased the scoreboard from the Yankees and had it trucked down to Philadelphia.)

But the one thing the Phillies and owner Bob Carpenter wanted the most was more parking. Shibe Park had been built in a time before the common man held ownership of the common car, and the 400 or so parking spaces underneath the stands could hardly meet the massive demand for vehicle parking in the 1950s. Carpenter tried time and time again to purchase land around the ballpark to expand the fans’ parking options, but he never succeeded. Frustrated with an aging ballpark in a deteriorating neighborhood, Carpenter began to wonder if he had made a mistake buying the joint.

Carpenter would eventually succeed where Mack and the A’s had constantly failed for years to achieve: The allowance to sell beer at the ballpark. Not that alcohol had never been consumed inside the gates; fans had always found it easy to smuggle in the brew, as did some of the players—usually pitchers on their day off, sneaking out of the bullpen and over to the corner of 20th and Lehigh to grab a drink to go from Kilroy’s, or Charlie Quinn’s Deep Right Field Café as it was known after 1935. Evidence that illegal drinking was prevalent inside Shibe became painfully obvious during one 1949 game that ended in a forfeit win for the visiting Giants, as angry fans littered the field with empty beer bottles and cans following a blown call that went against the Phillies. Midway through the 1961 season, the state finally gave the Phillies permission to sell beer—except on Sundays—and the fans needed it more than ever as the team, gradually slipping in the standings since their 1950 pennant, kerplunked to a 47-107 record punctuated by a modern record 23-game losing skid.

Drunk or sober, in good times or bad, the fans at Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium were always a special breed, loyal but often vicious in their vocal commentary. It was a disposition that would evolve and personify the stereotype of the Philadelphia sports fan. The rough banter went back to the 1920s with Bull and Eddie Kessler, who sold fruit from a cart before A’s games and then aired out their lungs inside the ballpark. They not only rode visiting players but some of their own, including the great Al Simmons; maybe he wouldn’t buy their fruit. Connie Mack tried to placate the Kesslers with season tickets and, when that didn’t work, a lawsuit. Neither worked.

The Kesslers were far from the only loudmouths at Shibe/Connie Mack. The A’s Gus Zernial once injured himself trying to catch a ball—and the fans gave him no mercy. “Announcer told fans I’d broken my shoulder,” he recalled, “took me down this tunnel and I could hear them booing me all the way down to the clubhouse.” The Cardinals’ Red Schoendienst once had to be restrained by police from going into the seats after a Phillies fan called him a Nazi. Then came the 1960s and Dick nee Richie Allen, an immense talent with an immense chip on his shoulder who rubbed fans and teammates the wrong way—most memorably with a racially-tinged, pregame brawl pitting himself and Frank Thomas (Allen was black, Thomas white). Allen’s impressive numbers weren’t enough to win over Phillies fans, some of whom got so savage that he had to wear a batting helmet in the outfield. When the Phillies mercifully traded Allen to St. Louis in 1969, the guy supposedly coming the other way—outfielder Curt Flood, another African-American—didn’t want any part of Philadelphia, refusing to play for a team and a city both recently torn by racial strife; he thus set into motion his landmark challenge to baseball’s reserve clause.

The Phillies gave the Grand Old Lady of Lehigh Avenue one last hurrah in 1964. Or at least they tried. With Allen in terrific Rookie of the Year form and a solid pitching tandem of Jim Bunning and Chris Short, the Phillies looked to be on their way to their first pennant since the 1950 Whiz Kids campaign, up 6.5 games with 12 to play. Then the improbable happened; they lost the next 10 games, the first seven of those at Connie Mack Stadium as young manager Gene Mauch panicked and tried to pitch an exhausted Bunning and Short on extreme short rest. When the Phillies came back to their senses from the myriad of knockout punches, they had finished the season tied for second, one game back of NL champion St. Louis. It was a collapse generally considered the greatest in baseball history.

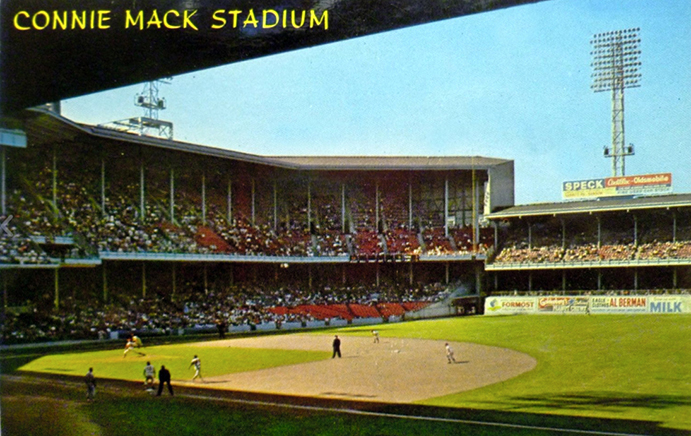

This postcard shows Connie Mack Stadium—as Shibe Park would be known starting in 1954—in its final setup with lights, red seats and advertisements on the outfield walls and atop the bleachers.

The Final Days.

That 1.4 million fans—the largest seasonal attendance ever garnered at Shibe/Connie Mack for either the Phillies or A’s—braved the trek to the ballpark was impressive. Race riots in the summer of 1964 had bordered up to the home plate entrance, accelerating the neighborhood’s urban decay and crime that had begun in the 1950s. Bob Carpenter continually tried to make Connie Mack Stadium look chic again, but after failing to land an American Football League team to gain additional revenue, he gave up—selling the ballpark in 1961 at a third of the price he had bought it for. The new landlord did little to improve or maintain the place, a depressing stain on a ballpark that the A’s had long bent over backwards to keep meticulously clean. Street parking was as unnerving as ever for fans who tried to avoid the gangs and other unwanted elements of the area—and once inside the turnstiles, Connie Mack Stadium proved no less a sanctuary as fan-on-fan hostilities worsened.

Talks intensified on a new multi-purpose stadium, something the Phillies eagerly hoped to see so they could split ASAP from Connie Mack Stadium. Alas, the wait would be a long one. Although voters approved what would eventually become Veterans Stadium in 1964, it would take a full seven years before it opened, thanks to spiraling budgets (which forced a second vote, in 1967) and bad weather.

On October 1, 1970, the 6,055th and final major league baseball game took place at Connie Mack Stadium between the Phillies and Montreal Expos. Fans didn’t wait until the last out to start the demolition. All throughout the game, the sound of seats and other artifacts being dismantled could easily be heard. One was morbidly nostalgic enough to extract an entire toilet. Some kid even tried to take off with one of the Phillies, left fielder Ron Stone. Anticipating the potential mayhem, the Phillies gave away 5,000 wooden seat slats to fans. The move backfired; the slats were used to help pry away actual seats. When the Phillies won in the 10th inning on Oscar Gamble’s walk-off single, the souvenir hunters went into overdrive, invading the field and grabbing anything they could. Some even tried to extract home plate but failed; it was eventually transported to Veterans Stadium. Amid the chaos, 35 people were hurt before the lights were shut off on Connie Mack Stadium for good.

Life After Baseball.

A more formal demolition was long in forthcoming; the ballpark sat abandoned as an omnipresence of weeds took hold, giving the place a look like something out of one of those Life After People episodes. In 1971, two kids broke a pair of cardinal rules: Don’t break into an abandoned building, and don’t play with matches. Perhaps they wanted to see if a ballpark built to withstand fire could, in fact, burn down. Turns out, much of it could. Connie Mack Stadium wasn’t entirely reduced to ashes, but it suffered major damage. Finally, in 1976—at the same time the All-Star Game was being played at Veterans Stadium—what was left of baseball’s first steel-and-concrete facility was torn down. Some of the few seats left untouched by thievery and fire were boxed up and sent to minor league facilities in Greensboro, North Carolina and Spartanburg, South Carolina, where they currently remain in use.

Today the religion of baseball has been replaced at the corner of Lehigh and 21st by religion itself. The extravagant Deliverance Evangelistic Church includes a 5,100-seat auditorium that probably brings in more people on a Sunday than the A’s and Phillies might have on occasion. The surrounding neighborhood seems to be on a mild rebound; it’s not gentrified, but a sense of community appears to have returned. The tract homes on 20th Street, which once were targets for Home Run Baker, Richie Allen and countless legends in between, no longer look dilapidated as they were in the years following the ballpark’s demise, showing off fresh coats of paint and other structural facelifts.

Over on the other side of where Shibe Park once stood lies a decent strip mall that features, among other noteworthy chains, a GameStop. It’s here where youngsters might stumble upon a baseball video game, put it on at home and set up a classic game at Shibe Park; maybe they’ll discover, as best as the digital gods could recreate, the environment where Connie Mack built up (and tore down) two dynasties, where Ted Williams achieved his “true” .400 in 1941, and where Brooklyn Dodgers rookie Jackie Robinson and Phillies manager Ben Chapman buried the hatchet from the latter’s vicious racial taunting of the former in 1947.

For the locals, Shibe Park held its share of baseball glory, and more than its share of baseball purgatory. Its initial beauty would be compromised and, as such, it would not age with grace. But it helped to keep Philadelphia on the baseball map for generations even if the teams that performed there often didn’t deserve the credit. That, for sure, goes to the ballpark and the loyalists who frequented it.

The Ballparks: Baker Bowl It was a ballpark ahead of its time when built and well behind the times when abandoned 40 years later, by then a ridiculed dump given a slough of unpleasant names. Steel and concrete gave little comfort for the poor souls victimized in a series of unfortunate events—and as spectators covered their heads from debris, the right fielders covered theirs from the balls constantly ricocheting off the tall and cozily placed tin wall behind them. Welcome to Baker Bowl: Enter at your own risk.

The Ballparks: Baker Bowl It was a ballpark ahead of its time when built and well behind the times when abandoned 40 years later, by then a ridiculed dump given a slough of unpleasant names. Steel and concrete gave little comfort for the poor souls victimized in a series of unfortunate events—and as spectators covered their heads from debris, the right fielders covered theirs from the balls constantly ricocheting off the tall and cozily placed tin wall behind them. Welcome to Baker Bowl: Enter at your own risk.

Oakland A’s Team History A decade-by-decade history of the A’s, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.

Philadelphia Phillies Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Phillies, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.