The Ballparks

Three Rivers Stadium

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Historic Pittsburgh

A card-carrying member of the Cookie Cutter Society, Three Rivers Stadium was the cookie that needed a bite taken out of it to reveal downtown Pittsburgh for those inside. Its enclosed nature was a necessity of compromise, a confluence of sports teams near a confluence of rivers, yielding a confluence of championship glory before tough times set in—most certainly for a Pirates team that found progress in the modern age a steep slope to climb.

In his heyday, everything King Midas touched turned to gold. The reverse could be said for the Pittsburgh Pirates and Steelers during the first of three decades they called Three Rivers Stadium home: Seemingly, everything the gold (and black) touched turned them into kings.

Yes, Three Rivers Stadium was another one of those venues people now love to hate: A perfectly circular hunk of concrete largely adorned with slightly angled spectator ramps perfectly spaced between four large welcoming gates. It contained a symmetrical monotony with all the personality of a breakfast buffet bowl—a bowl “detached from the river in a wasteland of parking areas,” wrote author Rob Lubove. “There’s no atmosphere in this thing,” said Hank Novak, a lifelong ballpark employee for the Pirates. “You’re in a bowl.”

Yet in the 1970s, Three Rivers Stadium was a super bowl, literally so for the Steelers—who went on to conquer four National Football League titles in their first 10 years playing at the stadium. The Pirates weren’t complaining either; they all but bookended the decade hoisting a pair of World Series trophies, while winning four other National League East Division titles. You could even throw in the University of Pittsburgh football team, which abandoned their own stadium on campus and borrowed Three Rivers for big games, most notably in a 1976 championship campaign featuring Heisman Trophy running back Tony Dorsett.

All good things come to an end. In the case of the Pirates, those good times—and high times, nudge-nudge—came crashing down upon them in a thoroughly depressing, scandal-ridden second decade to follow. Though they would recover, the bulk of their remaining time at Three Rivers Stadium was largely an excruciating exercise in debt-ridden futility—and even though some of the circumstances that led to their misfortunes were self-inflicted, it was clear that by the Bucs’ third decade at Three Rivers, a new home was badly needed.

The Long, Long, Wait.

The prescript to Three Rivers Stadium is a familiar one: Aging ballpark, long ago gorgeous and glittering, is beginning to age beyond repair. Baseball team, wallowing in a decrepit locker room, is growing restless for something new. Oh, and yes—local football team wants to join along.

Since 1909, Forbes Field was one of baseball’s more elite ballparks, an ornate palace for the National Pastime that the team and its fans could feel proud of. But postwar America had moved on from baseball’s Gilded Age; decaying relics of yesteryear had no place in a society focused on suburbia, interstates and 707s. Even the pleasing evergreen views beyond the fences from inside Forbes Field were rapidly being overcome by industry and other inevitable forms of development.

It’s not that the Pirates had a choice in Forbes Field’s fate—at least not after 1958, when they sold the ballpark to the adjacent University of Pittsburgh, which wanted to raze the structure for campus expansion.

The Pirates were not using the pending eviction to leave town; the university would, in fact, be patiently gracious in letting Forbes Field remain standing and active as long as the Pirates needed it. But city leaders, leery of the trend in franchise shifts within Major League Baseball, didn’t want to take any chances of losing its most fabled sports entity.

The initial chatter toward a modern stadium actually predated the university’s purchase of Forbes by a decade. Pittsburgh mayor David L. Lawrence first brought up the idea of a civic-owned sports building in 1947, but it would take eight years for joint city-county agencies to seriously begin pondering where, when and how. Deciding the ‘where’ was the easy part; little debate was spent on the choice to place a new stadium across from downtown on the north side of the Allegheny, an ugly hodgepodge of industrial blight strewn with abandoned warehouses and neglected trainyards. The particular spot for the new stadium was, in fact, once upon a time the same site as Exposition Park, the Pirates’ first home.

Away from the North Side, one wild thought was to build a massive land bridge over the Monongahela River that would hold a stadium sitting on top of a multiple-story parking garage accompanied by twin skyscrapers. Never mind the possibility of the 100-year flood wreaking havoc on such a complex structure; the U.S. Department of Defense was more concerned with the potentially devastating impact from an act of terrorism—before that word became a thing—and nixed the idea.

For the Pirates, time seemed to stand still on any progress toward an actual stadium. Not even their rousing World Series season of 1960, capped by Bill Mazeroski’s legendary walk-off homer in the seventh game against the New York Yankees, sped up the clock on any timetable. Forbes Field wasn’t getting any younger, the Pirates’ patience was thinning, and the university was standing by with the wrecking ball, fingers tapping on the lever. Five years after local authorities said yes to a new stadium, there wasn’t even a scope of work; the Fort Duquesne Bridge, conceptualized specifically to carry auto traffic from downtown Pittsburgh toward the stadium, was 90% complete—with the last 10% on hold until there was actual progress on the facility. Locals mocked it as the “Bridge to Nowhere.”

Worse, there was wrangling between the city of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, the latter beginning to balk on its financial contribution toward the stadium unless the Pirates and Steelers pitched in more. By this time, the Pirates publicly threw their hands up and declared that perhaps a move out of town wouldn’t be such a bad idea. If anything else, the threat brought the various public agencies together toward a budget agreement.

Architect Dahlen Ritchey’s early, dreamy rendition of Three Rivers Stadium consisted most notably of an open view of the Allegheny River and downtown Pittsburgh beyond. He was forced to go back to the drawing board when construction bids to realize his design were $10 million over budget.

Bureaucracy Over Beauty.

While public agencies battled over the finances, a local consortium of architects focused on the stadium’s aesthetics.

Providing the infrastructural design was Michael Baker International, a fast-growing firm which had a hand in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the Seattle Space Needle, and Pittsburgh International Airport, among many other projects around the planet. The look of the stadium, meanwhile, would be the responsibility of Deeter Ritchey Sipple (DRS), which drew up the beautiful downtown plaza Mellon Square and the highly acclaimed Civic Arena in Pittsburgh, the first sports structure with a retractable roof. DRS principal Dahlen Ritchey, who grew up a big Pirates fan and forever regretted the day he gave away his Game Seven tickets to the 1960 World Series (because he was sure the Pirates would lose), initially lobbied for separate side-by-side stadiums for the Pirates and Steelers—with the Bucs’ ballpark providing an open view beyond its outfield of downtown. Essentially, Ritchey envisioned PNC Park and Acrisure Stadium (formerly Heinz Field) four decades before they were built.

“The idea came from Forbes Field,” Ritchey told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2001 of his ballpark design. “You could sit in the stands and see Flagstaff Hill and Schenley Park. It was very nice. So the idea was to open it up and see the city.”

Ritchey was vetoed on the twin-stadium concept but, for the moment, was able to retain his open-air design for the multi-purpose concept. The model of the stadium, revealed at the end of 1964, was eye candy on a prime level; a 54,000-seat venue with an overhang that protected 70% of the fans, thinning out and angling downward toward the river; private suites; and two restaurants, one open year-round. It was a winner—until the construction bids all came in at $10 million above the projected $26 million cost. Ritchey’s unique design, using many customized components, was part of the reason—but so was inflation and an expected excess of overtime wages to build a stadium on a relatively fast turnaround.

Forced to go back to the drawing board, Ritchey had no choice but to artistically cave to the tight budget, designing a fully-enclosed stadium with a symmetrical build that appealed to a more cost-effective solution. Losing the view of downtown was a bitter bill for Ritchey to swallow; he would ultimately call Three Rivers Stadium his biggest disappointment as an architect.

As groundbreaking on the stadium finally took place in 1968, the Bridge to Nowhere finally got somewhere—and it wouldn’t be just to ferry traffic to Three Rivers. The plan was to build a whole mixed-use community around the stadium, including hotels, restaurants, a theme park, science center and marina—all connected by people movers. The North Side, that industrial wasteland, was making a serious bid to become the place to see and be seen in Pittsburgh.

Delays and some disputation peppered the building phase of Three Rivers Stadium. Numerous strikes in a city heavily represented by unions pushed back the scheduled first game from Opening Day 1970 to midseason; “Every day they delay making the move is taking money out of my pocket,” complained Pirates star slugger Willie Stargell, who had enough of Forbes Field and its endless outfield dimensions. Meanwhile, the naming of Three Rivers Stadium didn’t sit well with many Pittsburghers, who rather would have seen the facility named after David Lawrence, the mayor who first championed the idea of a stadium back in 1948.

The view from the top of Three Rivers Stadium during the first game played on July 16, 1970. Downtown Pittsburgh peaks over the top of the other side. The Pirates lost the inaugural contest to the Reds, 3-2. (Historic Pittsburgh)

“Admirably Practical…Devoid of Personality.”

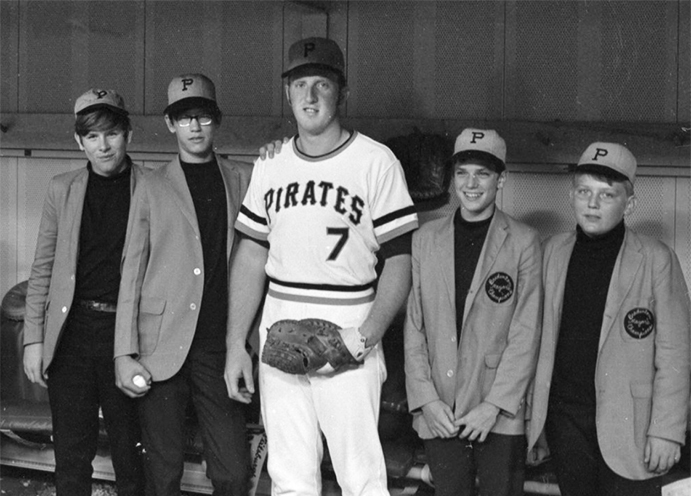

On July 16, 1970, they finally played ball at Three Rivers Stadium. There was some old-timey substance to the proceedings, as 71-year-old Pirates legend Pie Traynor threw out the ceremonial first pitch; Hollywood crooner and long-time Bucs fan/part-owner Bing Crosby was among the notables in the VIP section. But modern times also made for a strong presence. Besides the new stadium itself, there was synthetic Tartan Turf on the field, a cushier, more agreeable alternative to AstroTurf; and the Pirates broke out of the clubhouse as the first team to wear double-knit, buttonless jerseys. The novel look, which would catch on throughout much of the major leagues in the years to follow, yielded plenty of odd looks—and laughs—from the home fans, comparing the Pirates’ look to that of a weekend softball team, while one sportswriter said the unis reminded him of “long underwear.”

As for the game itself, the Cincinnati Reds—who just 17 days earlier debuted in Riverfront Stadium, the appearance and name of which would confuse many with Three Rivers—edged out the Bucs, 3-2. Tony Perez hit the stadium’s first home run, and scored the game-winner in the top of the ninth on Lee May’s single.

Three Rivers Stadium exhibited a number of growing pains from the first day on. At the first game, the water fountains didn’t work, access roads and parking lots hadn’t been fully completed, and only 13 of 35 concession stands inside the stadium were operational. An automatic tarp, which wasn’t so much meant to replace the grounds crew as it was to make their jobs easier, made everyone’s life miserable one night late in 1970 when it crashed back into the trench where it was stored; a rain delay became a suspension of the game until the next day while the apparatus was fixed.

Despite its ultimate reputation as a mundane hunk of concrete, Three Rivers Stadium did spark some personality with its exclusive Allegheny Club, located in the second level down the right-field line. Its spaciousness was evident from the outside; tall windows stretched upward and across, allowing patrons on cascading levels of table seating and barstools to enjoy the game while eating and/or imbibing. They could even look to the outside and see downtown, the three rivers and the hills beyond.

The Allegheny Club doubled as an ode to the past; it included a segment of Forbes Field’ famed brick wall, and a plaque honoring Babe Ruth’s final home run (hit at Forbes in 1935). It also featured a Pirates Hall of Fame which, at one stage, included wax figures of Honus Wagner, Pie Traynor and Roberto Clemente wearing the uniforms of their times. Players might have had a chance to enjoy the Allegheny Club after the game, but left fielders in particular didn’t care for it during; the reflection of the stadium’s lights off the club’s mass façade of windows made catching line drives in left an adventure.

There was much initial praise for Three Rivers as a civic stadium meant to pull the Pirates and Steelers out of far more rustic times, but the compromised tedium many would ultimately slam it and other so-called “cookie-cutter” stadiums for was still hardly lost on some even as it doors opened for the first time. The Sporting News’ Leonard Koppett admitted that Three Rivers and its modern ilk were “admirably practical buildings, containing creature comforts and working facilities undreamed of in the old days,” but he well understood their flaws. “They are devoid of personality, emotionally indistinguishable even when one knows perfectly well their specific different characteristics,” he wrote.

Three Rivers Stadium presented itself as a fairer alternative to Forbes Field with its boilerplate field dimensions; no longer did Willie Stargell nor any other player have to drive a ball 400 feet and then hope that it cleared the fence. Stargell was a man of such power, nothing at Three Rivers seemed to be outside of his reach.

On August 9, 1970—less than a month after Three Rivers’ opening—Stargell deposited his first of four home runs he would launch into the stadium’s upper deck. He hit three of them before anyone else did it even once. Stadium officials notated the spot where they landed by later painting numbers on it.

Overall, eight other home runs would reach the upper deck in the 30-year history of Three Rivers; the only player, besides Stargell, to reach it multiple times would be Jeff Bagwell, who never played for the Pirates and needed only 57 games as a member of the visiting Houston Astros to do it twice.

After getting used to Three Rivers for half a season in 1970, the Pirates’ first full campaign at the stadium a year later resulted in their first world title since their fabled 1960 run at Forbes Field. Stargell came alive with a career-high 48 homers (his previous high at Forbes was a relatively mere 33), but he wasn’t alone on the star chart. Roberto Clemente, aging like fine wine at 37, batted .341 and dominated the postseason to follow—hitting .387, shining on defense from the outfield, and earning World Series MVP honors as the Bucs came back from an early 2-0 series hole to defeat the Baltimore Orioles in seven games.

Though spacious Forbes Field was perfectly suited for Clemente’s brand of line-drive hitting, he found Three Rivers to be no problem. Over 494 career at-bats at the stadium, he batted .337; no other player had a higher average in as many at-bats at Three Rivers. On September 30, 1972, Clemente collected his 3,000th career hit with a fourth-inning double; it would be his last hit of the season—and, alas, the last of his career. Following the season on New Year’s Eve, Clemente boarded a DC-7 in his native Puerto Rico on its way to Nicaragua to provide aid for victims of a recent earthquake; the plane crashed into the Atlantic Ocean moments after takeoff, killing Clemente and four others onboard. In the aftermath of his death, fans and reporters alike lobbied to have Three Rivers renamed after Clemente, but the effort never gained enough traction.

Posing with a group of kids, Pirates first baseman Bob Robertson shows off the buttonless, double-knit uniforms broken out for the first game at Three Rivers Stadium. Initially mocked for looking like everything from a softball jersey to pajamas, the synthetic unis would start a trend that virtually every other major league team would catch on with during the 1970s and beyond. (Historic Pittsburgh)

An Immaculate Rise.

If Three Rivers Stadium gave the Pirates an early boost, it completely transformed the Steelers into a long-term powerhouse.

Forty years earlier, Art Rooney had paid $2,500 he had floating around from winnings at the racetrack to purchase an expansion National Football League team in Pittsburgh. The son of a saloon owner who ran a favored watering home for baseball fans in the Exposition Park era, Rooney—himself not too bad a minor league ballplayer—first named his team after the Pirates before changing it to the Steelers in 1940. “Doormats” would have been more appropriate; as the Steelers bounced around Pittsburgh without its own stadium, they were traditional losers who made only one postseason appearance in 37 years—losing 21-0—before moving into Three Rivers.

The Steelers warmed up from scratch in their first two years at Three Rivers, with a young, taciturn head coach (Chuck Noll) who made bland wallpaper exciting, and a hotshot Louisiana-born quarterback (Terry Bradshaw) learning the ropes at the pro level. In 1972, the Steelers made the postseason—which itself was big news—but the franchise’s coming-of-age moment occurred in their first playoff game with, arguably, the most memorable play in NFL history.

Having just fallen behind at Three Rivers to the Oakland Raiders by a 7-6 score, the Steelers were 22 seconds away from defeat and facing fourth down 60 yards from the Raiders’ end zone. Bradshaw, desperately escaping Oakland defensive linemen, somehow managed to heave a 35-yard throw down the middle toward running back John Fuqua—who was drilled to the ground by hard-hitting Oakland defensive back Jack Tatum. The force of the collision ricocheted the ball back 10 yards—where it was plucked inches off the ground by breakout rookie running back Franco Harris, who lumbered the final 45 yards down the sideline, barely evading numerous Raiders players and into the end zone with the winning touchdown.

As delirious Steelers fans jumped the stands and flooded the Three Rivers turf, referees sought to determine which player Bradshaw’s pass had deflected off of; at the time, an offensive player could not legally catch a ball deflected directly from a teammate. Oakland head coach John Madden often told the story of what happened next: The refs got on the phone and asked stadium officials if they could guarantee their safety off the field. When they were told no, they put up their hands and signaled touchdown. (The story is disputed, but it’s a good one.)

The Steelers would lose the following week at Three Rivers to the Miami Dolphins—on their way to being the first undefeated team in the Super Bowl era—but the Steelers permanently shed their loser image, beginning a brilliant run of football that would net them four Super Bowl trophies over a six-year period. Fans embraced the Steelers in a way never felt by the Pirates; blue-collar fans somehow scraped up enough cash to fill the joint over and over again—from 1972 on, the Steelers sold out every game at Three Rivers—and formed rabid fan groups celebrating players from Franco Harris to placekicker Roy Gerela. While the Pirates represented baseball tradition, the Steelers represented Pittsburgh—“Tough, hard-nosed, grim-featured, not so fancy,” wrote The Sporting News’ Furman Bisher.

A Family Affair.

The championship chic of Three Rivers Stadium’s first decade would hit a celebrated crescendo in 1979. The Pirates may have been overtaken by the Steelers as Pittsburgh’s most adored, but they still had Mojo; an aging but still dangerous Willie Stargell was joined by a colorful cast of characters that included burly MVP-level slugger Dave Parker, the tirelessly skinny and bespectacled reliever Kent Tekulve, and 6’7” starting pitcher John Candelaria, who threw the Bucs’ first no-hitter at Three Rivers in 1976.

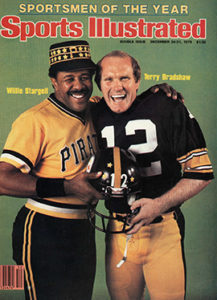

Champions in arms: The Pirates’ Willie Stargell and Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw earned co-Sportsmen of the Year honors by Sports Illustrated in 1979. Both the Pirates and Steelers won it all that year, capping a sensational first decade at Three Rivers Stadium in which both teams combined for six championship titles (Sports Illustrated)

Donned with multiple, vivid uniform combinations of black, gold and pinstripes, the Pirates intensified their exciting brand of ball, particularly excelling at Three Rivers; during a last-gasp effort to steal the 1978 NL East title from the Philadelphia Phillies, they won a major league-record 24 straight games at home. That late surge fueled a 1979 season in which a lively unit, led by clubhouse father figure Stargell, won nearly 100 games, swept the Cincinnati Reds in the National League Championship Series and, in a virtual repeat of their 1971 world title, again faced the Orioles—and again came back from two games down, winning the final three contests for their second (and last) World Series conquest in the Three Rivers era. The fans celebrated in the streets to Sister Sledge’s We Are Family, the Pirates’ adopted theme song of the 1979 campaign; Stargell, for his combination of sage and vintage strength at age 39, won co-NL MVP honors (with St. Louis’ Keith Hernandez) and the straight MVP for both the NLCS and World Series.

Stargell would share one last honor at year’s end—being given Sports Illustrated’s prestigious Sportsman of the Year award along with Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw—“Two champs from the City of Champions,” the magazine boasted.

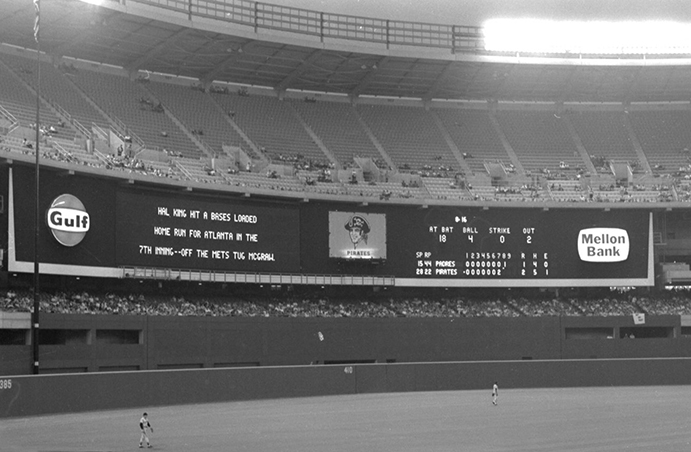

Three Rivers Stadium’s original scoreboard extends out above the outfield wall. Costing $1.5 million, the board would be replaced after just 13 years by a Jumbotron placed higher up in the top deck. (Historic Pittsburgh)

Highs and Depressions.

After reaching such heavenly highs in Three Rivers Stadium’s first decade, the Pirates almost had nowhere to go but down in the 1980s. But few expected the team to plummet deep into the Hades of Baseball.

In 1979, the Pirates introduced the Pirate Parrot, a mascot patterned after the successful debut of the Phillie Phanatic in Philadelphia a year earlier. The Parrot was an instant hit and remains a popular asset to this day at PNC Park. Ballplayers initially embraced the Parrot as well—though not for the same reason as the fans.

Underneath the big furry costume was Kevin Koch, the Pirate Parrot’s first portrayer—and, as it would infamously be revealed, a cocaine user and middleman between dealers and ballplayers in both clubhouses. Koch would even get high on his own supply while doing Parrot duty, which must have made for the most kaleidoscopic experience by an employee of the Pirates since Dock Ellis claimed he threw a 1970 no-hitter on LSD.

Koch received most of the cocaine from a freelance photographer named Dale Shiffman, who in later grand jury testimony claimed that two-thirds of the Pirates’ roster were buyers. The Three Rivers clubhouse was derisively nicknamed “The National League Drugstore,” the focal point for Baseball’s biggest drug scandal; not only did it result in a 12-year prison sentence for Shiffman (Koch became an informant and ratted him out), but it also forged testimony from some of his major league clients, big names such as Dave Parker, Keith Hernandez and Tim Raines—who were all granted immunity to talk.

The scandal devastated the Pirates’ organization; the team sank in the standings, bottoming out with a 104-loss campaign in 1985. Attendance, abetted by a full-blown depression in Pittsburgh with 23% unemployment at one point, dipped well below a million; in 1983, the Pirates drew their smallest-ever crowd at Three Rivers when a gathering of 1,970 showed up. Dave Nightengale wrote of the stadium having all the life of a funeral parlor.

Pittsburghers Will be Pittsburghers.

One silver lining to perhaps emerge from the Pirates’ lack of fans during the 1980s is that there were fewer of them to abuse the players. Verbal hostility from spectators in state of Pennsylvania wasn’t just restricted to Philadelphia; Forbes Field was somewhat notorious as a place for fans who did more than boo. The Pirates’ move to Three Rivers Stadium failed to domesticate the base.

Dave Parker had batteries thrown at him in the field; his Pirates teammate of five years, outfielder Lee Lacy, had bottles tossed toward him. Roughly a decade later, outfielder Andy Van Slyke had a cigarette lighter thrown in his direction; upon picking it up, Van Slyke read an attached message that said, “Use this to light a fire under you.” His teammate, Bobby Bonilla—in the midst of an All-Star season in 1988—was heavily booed at Three Rivers because his home batting average was 100 points lower than on the road. The rancor became so R-rated that, by 1985, the Pirates set up a G-rated family section at Three Rivers that forbade profanity and alcohol.

When Parker, who once said, “Money isn’t everything—peace of mind is important to me,” hit free agency in 1983, he wasted no time fleeing Pittsburgh. Returning the following year as a member of the Reds, the Pirates wasted no time abetting the acrimony from his former fans. The team proudly released a chart of the loudest decibel level counts during each of Parker’s at-bats in his first game back at Three Rivers as a member of the Reds.

The Steelers, surprisingly, were not immune to the fans’ bully ethic. Terry Bradshaw was a frequent target of boos—but his successors at the quarterback spot fared far worse. The reason for the only sellout in the short (one year) history of the United States Football League’s Pittsburgh Maulers at Three Rivers was so that fans could rain boos and ice upon former Steelers QB Cliff Stoudt, appearing for the visiting Birmingham Stallions.

But topping all of the above has to be, by all accounts, the most bizarre incident in the history of Three Rivers Stadium. In December 1987, an evidently deranged man managed to drive his car through the stadium and out on the field—in the process, barely missing four employees but not several trucks carrying barrels of nacho cheese, much of which ended up covering his car. The man got out, ran onto the field and began kicking footballs through the goalposts. After his arrest and asked to explain his lapse into mental freefall to do all of these things, the man put the blame on Steelers quarterback Mark Malone, who was finishing up an awful (46% completion rate, six touchdowns, 19 interceptions) season for Pittsburgh.

As bad as sports fans were at Three Rivers, those attending concerts were even worse. A 1973 Led Zeppelin concert nearly turned into a riot; a year later, Eric Clapton was nailed in the face by a (perhaps) errant frisbee. When 70,000 people—many without tickets—attempted to force their way into a 1976 concert featuring ZZ Top and Aerosmith, leading to an injury count of at least 250, public officials debated whether to end rock music acts at Three Rivers. But the debt needed to be paid and the crowds, as misbehaved as they often were, were massive.

Eventually the 1980s came along and concert crowds began to mellow with age. Without a hitch, a 1985 Bruce Springsteen gig at Three Rivers drew 65,000, the largest gathering for any event at the stadium. It was followed closely by crowds of 60,000-plus for the Rolling Stones and Genesis. Three Rivers’ last concert featured N’Sync in July 2000, drawing 47,000.

A look at Three Rivers Stadium from the top of the upper-deck bleacher seats. Breaking up the symmetry in the middle deck at left is the Allegheny Club, an expansive restaurant and lounge seating up to 700. (Jerry Reuss)

Winning, Then Losing.

Three Rivers Stadium never worked out for the Galbreath family, which had owned the Pirates since 1946. By the time it put the team up for sale in 1986, the Galbreaths lost $18 million in 15 years at Three Rivers, making a profit only during the ballclub’s first full season there (1971). Buying was a consortium of private and public sources, meant as a stopgap to keep the team in Pittsburgh and buy time to find a longer-term owner who had yet to come along. (It would take 10 years for that person, Kevin McClatchy, to fully purchase the Bucs.)

From the ashes of the drug-infested, small-crowd doldrums of the mid-1980s, the Pirates rose like a Phoenix to be reckoned with at the end of the decade. No-nonsense manager Jim Leyland presided over a young and highly talented outfield that included Bonilla, Van Slyke, and a tantalizing five-tool legacy named Barry Bonds, who omitted occasional raw flashes of greatness before ascending to more consistent MVP levels.

The first three years of the Pirates’ final decade at Three Rivers Stadium witnessed the fruits of their labor, winning the NL East each season from 1990-92. Almost as surprisingly, the fans returned—drawing over two million in both 1990 and 1991, the only two times they would reach the figure at Three Rivers. But a return to the championship podium, reviving memories of Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell, remained elusive; they lost the 1990 NLCS to the Reds in six games, led the 1991 NLCS against Atlanta three games to two before being shut out twice at Three Rivers to bow out, then lost again to the Braves in 1992 when, with a 2-0 lead going into the bottom of the ninth in Game Seven, they gave up three runs to suffer a third straight pennant defeat.

Heartbreak segued to an even more depressing reality. Baseball’s acceleration of free agency dollars exposed the widening gulf between big and small markets, and the Pirates clearly represented the latter. The perfect storm hit the Bucs after the 1992 season, facing an offseason in which free agents Bonds, ace pitcher Doug Drabek and Gold Glove second baseman Jose Lind all departed for richer teams in bigger markets because the Pirates simply lacked the capital to retain them. The exodus buried the Bucs into eternal losing mode, while the situation made Three Rivers Stadium outdated and an obstacle to the future just as a new generation of popular, revenue-generated retro ballparks quickly began to rise in the horizon. Thirty years after feeling stuck and helpless at an aging Forbes Field, the Pirates began to get that sinking feeling all over again at Three Rivers.

In the 1990s, the Pirates reduced capacity at Three Rivers Stadium by 10,000 simply by tarping seats in the upper deck, where very few were likely to sit as the team descended into an historic long period of losing. (Flickr—Joel Dinda)

Dressing Up the Corpse.

By the mid-1990s, nobody was making money at Three Rivers, except the Steelers—who continued to sell out every game. But the Steelers, benefitting from a generous NFL revenue sharing system badly lacking in MLB, played only 10 home games a year, not 81—and so the stadium sat drowning in nearly $50 million in debt, while the Pirates were losing up to $10 million a year, borrowing more millions just to stay afloat and knocking heads with the stadium authority to sweeten the Three Rivers lease as they had been doing for years. Meanwhile, the team found that their only way to replace Barry Bonds was to stick Al Martin in left field every night.

While the Pirates and the public powers couldn’t tear down Three Rivers and copy Oriole Park at Camden Yards upon its footprint—not yet, anyway—they did try to give the stadium a more colorful and cozier vibe. They slapped tarps in the upper reaches of the top deck to reduce capacity by 10,000; placed ads on the outfield walls; opened a café behind the left-field fence, which had slats cut out so patrons could view the game; replaced the original red-and-gold seats with new ones painted in blue; and opened a full-scale restaurant, featuring two bars serving microbrews, near the southeast entrance with glass windows looking out towards downtown Pittsburgh. Outside of the gates, an homage to the past was erected with the placement of a Roberto Clemente statue.

While Three Rivers was receiving its late prepping up as the fight over whether to build a new ballpark continued, the area surrounding the stadium remained dormant, a head-shaking lack of mixed-use development promised by the stadium authority decades earlier. Phil Hundley, a Deeter Ritchey Sipple architect who was not intricately involved in the Three Rivers Stadium project but was around in 2020 to talk about it, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: “It had retail. It had hotels. It had office buildings. It was just going to be packed on the North Side.”

But nothing came of it. Nothing. Except, according to the Post-Gazette’s Robert Dvorchak, for a gas station which closed in 1980, unable to make a profit. And while the Bridge to Nowhere did get complete and got somewhere, some of the other promised access roads around the stadium never materialized. “If 25,000 people go (to Three Rivers) for a game,” said one-time Pirate Phil Garner to The Sporting News, “most of them will still be there two hours after the game.”

The Luxury of a Lame Duck.

In the summer of 1998, Three Rivers Stadium receive its death sentence with the approval of PNC Park and Heinz Field, side-by-side facilities built exclusively for the Pirates and Steelers, respectively. That brought instant sentimentality of a kind upon a facility derided for so long by fans, but now embraced as a much-needed link from the iconic days of Forbes Field to the future days that lay ahead at the new venues. Although the Pirates, in the midst of a two-decade stretch of losing unparalleled in pro sports, were awful over Three Rivers’ final two years, they managed to never draw a crowd under 10,000. Perhaps a live ball was helping to bring the fans in; Three Rivers yielded a stadium-record 171 home runs in 1999—then 172 in 2000.

On October 1, 2000, the Pirates played their final game at Three Rivers. Sister Sledge, the We Are Family authors from the Bucs’ fabled 1979 campaign, reunited to sing the National Anthem. Dock Ellis and Manny Sanguillen, the battery for the first game back in 1970, threw and caught the ceremonial first pitch. The only Pirate who wore a jersey for the very first game and this, the very last, was bench coach Richie Hebner, who started at third base in Three Rivers’ inaugural game, attracted ladies with his good looks and boos from everyone else for his subpar defense, and later criticized the stadium by stating, “My father’s cemetery has more life in it than this ballpark.” A crowd of 55,351, the largest ever to see a baseball game at Three Rivers, watched as the Bucs blew a late lead and bowed to the Chicago Cubs, 10-9.

Despite the last-game loss, Three Rivers ended up being very, very good for the Pirates—at least on the field, where they finished with a 1,324-1,081 record. The Steelers were significantly better at the facility that turned them from laughingstocks to conquerors, winning 182 of 254 home games and another 13 of 18 playoff games. They received the honor of hosting the very last event at Three Rivers, easily dispensing of the Washington Redskins, 24-3.

“The Greatest Day of My Life.”

On a chilly February morning in 2001, over 20,000 people picked out vantage points at a safe distance to watch Three Rivers Stadium implode to the ground, leaving a cloud of dust that drifted upon the Allegheny like a creeping fog bank. A 16-year-old boy won a raffle to push the button that began the detonation. “This is the greatest day of my life,” he told reporters. Many other witnesses agreed.

Three Rivers Stadium lives on in many different ways. The stadium’s only physical feature that remains where it once stood is an obelisk-style beacon for Gate D, which could be found in a grassy area outside the south end zone of Acrisure Stadium. Numerous seats were auctioned off, including 3,727 of the blue field level seats—snapped up by the minor-league Long Island Ducks. The Jumbotron scoreboard, which replaced the original board that extended below the upper deck behind center field, received a high bid of $475,000 from a Massachusetts company that carted it about for various events. Three Rivers’ structural concrete was grounded down and recycled for nearby parking lots.

Even after its implosion, Three Rivers Stadium continued to live on in the bills of taxpayers, who still had to help pay off $40 million of debt on the facility. It took 10 years to wipe it off the books.

Dahlen Ritchey’s vision of side-by-side facilities for the Pirates and Steelers, surrounded by a profusion of development, has finally been realized—even if it came one generation of sports venue ethos later than expected. PNC Park grandly looks out toward downtown Pittsburgh and is constantly acknowledged as one of baseball’s best ballparks. Adjacent Acrisure Stadium, clad with 68,000 yellow seats, retains the rabid enthusiasm of Steelers fans. With both facilities have come collateral development only dreamed about a half-century earlier, with a modern mix of parking, dining, business and green space; per example, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has relocated its headquarters right at the point where Three Rivers’ southeast (Gate C) entrance was once located.

Alas, bureaucracy won the day over beauty and urban community. Three Rivers Stadium stood alone, literally, as another cookie cutter, or concrete donut, or bowl. Like all the other stadiums of its ilk and time, Three Rivers became an unattractive yet necessary link from ancient times to the modern age.

It served its purpose. Nothing more.

The Ballparks: Forbes Field Removed from downtown Pittsburgh’s choking smoke and untamed rivers, elegant Forbes Field was built in a vernal, cultural paradise on the outskirts of town, where three was the magic number—from three Pirates world titles to Babe Ruth’s last three homers to the last tripleheader to all those triples. Wagner, Kiner and Clemente could all agree that excitement was never in short supply at the Old Lady of Schenley Park.

The Ballparks: Forbes Field Removed from downtown Pittsburgh’s choking smoke and untamed rivers, elegant Forbes Field was built in a vernal, cultural paradise on the outskirts of town, where three was the magic number—from three Pirates world titles to Babe Ruth’s last three homers to the last tripleheader to all those triples. Wagner, Kiner and Clemente could all agree that excitement was never in short supply at the Old Lady of Schenley Park.

The Ballparks: PNC Park If the Pittsburgh Pirates sense that they’re being ignored by their faithful at PNC Park, they shouldn’t take it personally; after all, the team’s only competition isn’t sitting in the visitors’ dugout. Spectators are easily distracted by mesmerizing views of downtown Pittsburgh, the Allegheny River and the Sixth Street Bridge, now named after Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. After thirty years of being locked in at Three Rivers Stadium, who can blame them?

The Ballparks: PNC Park If the Pittsburgh Pirates sense that they’re being ignored by their faithful at PNC Park, they shouldn’t take it personally; after all, the team’s only competition isn’t sitting in the visitors’ dugout. Spectators are easily distracted by mesmerizing views of downtown Pittsburgh, the Allegheny River and the Sixth Street Bridge, now named after Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. After thirty years of being locked in at Three Rivers Stadium, who can blame them?

Pittsburgh Pirates Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Pirates, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.