The Ballparks

Tiger Stadium

Detroit, Michigan

For a city that prides itself on automotive excellence, Detroit managed to get a century’s worth of mileage out of Tiger Stadium, a deceptively intimate ballpark that was periodically tuned up and souped up within its white walls. The Tigers may have moved on, but “The Corner” perseveres as a vivid, lasting memory—just as it did through boom, bust, urban decay and the many attempts to tear it down.

There was a time when the corner of Michigan and Trumbull Avenues, a mile west of downtown Detroit in the community of Corktown, thrived with the hustle and bustle of baseball tradition going back to the end of the 19th Century. Ten years into 21st Century, that time was gone. The signpost identifying one of Michigan’s most famous crossroads was lonely, surrounded by abandoned, decaying buildings, old establishments too proud to fold shop and a few modern fast food joints, all spaciously dotted between naked concrete foundations and grassy plots along U.S. Highway 12, itself a relegated, brittle red brick frontage road to nearby I-75. The surrounding expanse that once yielded an endless panorama of businesses, homes and shade trees, was now a semi-bucolic vista, a strange sight given its close proximity to downtown.

Corktown’s ballpark was gone as well. Tiger Stadium was the anchor, the glue, the star that kept the area brimming with life. Little now remained of it. The field was there, diamond and pitching mound included, kept game-ready by loyal volunteers for those willing to go nine innings on grounds where legends like Cobb, Gehringer, Greenberg, Kaline and Whitaker & Trammell once ruled. The 125-foot flagpole remained standing in center field, very much in play as it was for all those years while shadowed by fences and bleachers. Along Michigan Avenue, a strip of the elegant, arch-topped wrought iron fencing endured, looking all but lost and in search of a palatial residence to guard as it came to a sudden end halfway down the block toward Cochrane Street.

A handful of common benches and picnic tables surrounded both baselines, the only seats on a property that once housed over 50,000 of them. Folks could sit and imagine the staggering amount of baseball history that took place around them throughout the 20th Century. Because as William Faulkner once wrote: “The past is not dead, it is not even past.”

A Wooden Prologue.

Baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull Avenues—or “The Corner,” as it is simply known to generations of Tigers fans—predates Tiger Stadium’s original structures by 16 years. Bennett Park, a wood-built setting all too basic for the 19th Century, breathed the game’s first life into The Corner in 1896 for a Tigers team participating in the Western League, Ban Johnson’s warm-up act for an American League circuit the Tigers would advanced to in 1901. The facility was named after Charlie Bennett, a popular player back in the days of the Detroit Wolverines who invented the chest protector and was annually ranked as baseball’s top catcher in terms of Defensive Wins Above Replacement—astonishing not so much because was so good, but that modern sabermetric nerds could cull enough numbers from minimalist 1800s baseball stats to determine such rankings. It was all résumé-worthy info for Bennett. This, on the other hand, was not: A few years earlier, he lost both his legs after being run over by a slow-moving train he slipped getting off it. Bennett was beloved enough that he threw out the ceremonial first pitch for every home opener at The Corner from its 1896 debut until his death in 1927, long after his name had been removed from the entry gates.

Like most 19th Century ballparks, Bennett Park had its share of quirky hazards. It was built on a the site of a former hay market laid out in cobblestones, which were never removed; a thin layer of soil placed atop was sometimes not enough to keep the bricks from peaking through and causing mischief for a fielder or the ball he chased down. The park’s capacity, which gradually grew from 5,000 to 14,000, did not include several tall, precarious stacks of outlaw bleachers built on home properties behind the left field fence for landlords to make a little extra money on the side. Tigers management was unhappy, but the hitters only wished the bleachers were taller; the field was oriented so the sun set behind left, and mid-afternoon starts made squinting and eye-shielding a common occurrence at the plate as the game reached the late innings.

Detroit’s graduation to the majors in 1901 had been viewed as dubious. The city was one of the smallest big league markets at the time and the Tigers were consistently at or near the bottom of the AL’s attendance charts. Ty Cobb’s quick ascension to superstardom in the late 1900s, and the trio of AL pennants he helped bring from 1907-09, surely helped the gate, but that still didn’t prevent the occasional poor turnout—such as the 6,201 who found their way to the final game of the 1907 World Series at Bennett Park, the smallest crowd count ever for a Fall Classic contest. Ban Johnson, who as Supreme Being of the American League’s early years had the power to do whatever he pleased, repeatedly toyed with the idea of forcing the Tigers to move elsewhere. Perhaps he stayed patient because Frank Navin, who bought into the team in 1907 and quickly soon after became its primary owner, told him that a change was a comin’ to Detroit.

Navin wasn’t kidding. Detroit’s population swelled from 285,000 in 1900 to 465,000 in 1910, and doubled within another 10 years. Much of the growth was attributed to the burgeoning U.S. auto industry that the city all but monopolized, as car production mushroomed from 3,000 in 1901 to 166,000 1911 to 1.7 million in 1921. Navin knew that in order to accommodate the potential for bigger audiences, Bennett Park had to go.

Navin’s Field.

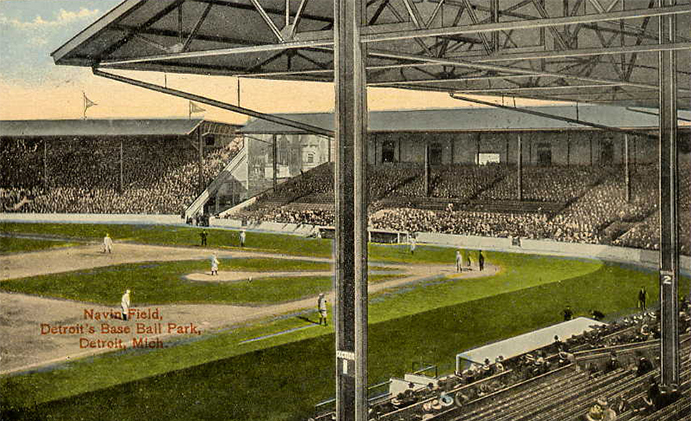

Everything was torn down and rebuilt from scratch, as the Tigers chucked the lumber and jumped on the steel-and-concrete bandwagon to join the rest of the modern baseball world. A covered grandstand wrapped from first to third base, with seats painted yellow (later green for the long haul); an additional grandstand was placed further down each line and was slightly rotated inward toward the infield. Crucially, the field was turned 90 degrees clockwise so hitters faced the northeast and not the setting sun, also thus spelling the end to the “wildcat” bleachers as the homes they were built upon were bought out and bulldozed—as were homes behind the new left field on Cherry Street, lest a new batch of unauthorized seats sprouted up. An out-of-town scoreboard was placed in left and slightly violated past the top of the outfield wall; an uncovered bleacher section sat isolated from right-center to center, cutting into what otherwise might have been a purely square-shaped ballfield.

A homelike touch was added at Michigan and Trumbull—now closest to the right-field corner—with a separate structure using Spanish-style overtones serving as the main entry. In terms of its location, aesthetics and functionality, the three-story ‘house’ mimicked Cleveland’s League Park and would itself be copied by Boston’s Braves Field three years later. Most fans entering through the entry would walk up a long ramp that would bring them to the top row of the main grandstand, along the first-base side.

Originally named after its owner, Navin Field debuted on the very same day as Boston’s Fenway Park, two days after rains scuttled the original premiere date. For the 26,000 who packed the 23,000-seat ballpark, it was a thrilling day worth the soggy wait; the Tigers’ Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford, one of the game’s greatest hitting duos, performed two double-steals in the first inning alone—with Cobb swiping his first of an eventual record-setting eight steals of home—and Detroit survived the new yard’s inaugural game in 11 innings over Cleveland, 6-5.

A postcard illustration of Tiger Stadium, shortly after it opened as Navin Field in 1912. The main, single-deck structure surrounding the infield was flanked by additional grandstands down each baseline.

Navin Field initially played like a typical deadball era ballpark with spacious dimensions; it was 345 feet down the left-field line, 370 down the right, and a roomy 467 to the deepest reaches of center. Home runs were thus predictably scarce, as the Tigers were lucky to get 10 of them at home during an entire season; in the war-shortened (128 games) 1918 campaign, they trotted through a mere two. Then came the 1920s, and an era of exploding offense throughout baseball; the Tigers certainly took advantage in one aspect by often hitting over .300 as a team—including an all-time AL-record .316 mark accomplished in 1921—but home runs remained a touchy subject for Cobb, now multitasking as both star hitter and manager. Cobb clung to deadball era strategies of aggressive station-to-station play and frowned on “easy” four-baggers, prioritizing the 10-foot bunt single on an infield made marshy because he always told grounds keepers to wet down the grass and make life difficult for fielders trying to grab the ball without slipping on their butts. The Tigers, force-fed the gospel, continued to pound out singles, doubles and triples under Cobb’s watch while few homers were belted.

Opponents—many of who scratched their heads when they came to Navin Field and saw the infamous sign that read, “Visitors’ Clubhouse—Positively No Visitors Allowed”—had no such restrictions slamming away. They frequently outhomered the Tigers at Detroit by a 2-1 ratio, and no visitor thrilled the locals more than, naturally, Babe Ruth. The legendary New York Yankee slugger hit two of his most famous home runs at Navin Field: A 1926 tape-measure shot to right field that likely was the longest of his career, reportedly measuring 626 feet on the fly and another 200 bouncing down Plum Street; and his 700th career homer, recorded on July 13, 1934.

The great Jimmie Foxx also got a kick out of playing at Navin Field, and the Tigers knew it. After the muscular slugger drilled nine home runs in 11 games for the Philadelphia A’s at Detroit in 1932, the Tigers pitched up an extra 20 feet of screen, unofficially labeled the Jimmie Foxx Spite Fence, atop the left-field wall for the next season. Foxx’s home run output was reduced to two, but he made up for it by batting .513 in 39 at-bats. Overall, Foxx’s career numbers at The Corner were some of the most impressive ever put up by a visitor; in 160 games, he hit .326 with 52 homers and 144 runs batted in.

A Little Here, a Little There.

As Detroit grew, so grew Navin Field. Attendance was sluggish during the 1910s as world war and inconsistent performances by the Tigers (Cobb’s batting greatness notwithstanding) created obstacles. But the postwar boom and the Tigers’ engorging offense—highlighted by an aging yet still potent Cobb and four-time batting champion Harry Heilmann—combined with the city’s rapid growth energized the box office. The Tigers led the AL in attendance for the first time in 1919, and five years later became the second major league team (after the Yankees) to bring a million fans through the turnstiles. About a thousand of those invaded the field one late spring day and participated in one of the ballpark’s more ugly incidents, as a brawl between the Tigers and Yankees that grew into a borderline riot before order was restored, the game forfeited and suspensions handed out.

When the Tigers were infused with additional financial muscle following the arrival of new co-owners including auto magnate Walter Briggs, funding became available for the ballpark’s first expansion in 1923. Capacity was upped to 29,000 as the main grandstand was topped by a second deck, itself topped on the roof by a new press box. The ballpark’s exterior, with its off-white walls, leisurely spaced dark windows and flat-topped roofs, began looking more and more like the facility people would become familiar with over the next eight decades.

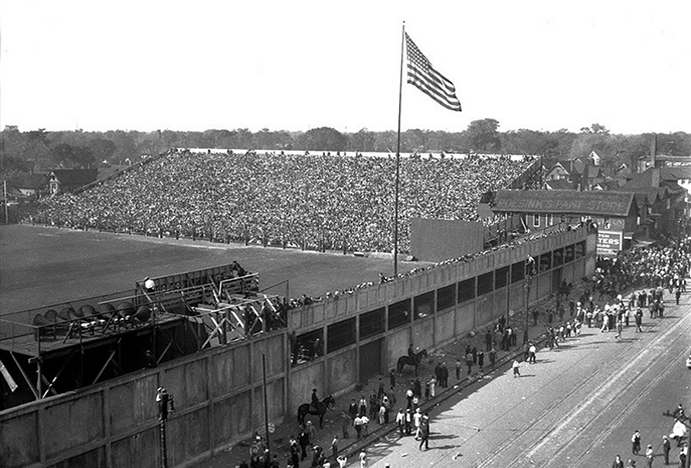

The next expansion, in 1934, was a temporary response to the team’s surge back into the limelight thanks to fiery catcher-manager Mickey Cochrane and hitting greats Hank Greenberg and Charlie Gehringer, all of whom lifted the Tigers to their first pennant since the early Cobb years—while lifting attendance back over a million. A massive, uncovered bleacher section totally incongruous to the rest of the ballpark structure was quickly built behind the linear left-field wall, in time for the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. The 17,000-seat section was so big that the Tigers successfully lobbied the city to reroute Cherry Street further back behind the seats.

Joe Medwick could have done without the bleachers. The ornery St. Louis star had finished off a triple in Game Seven by aggressively sliding into Detroit third baseman Marv Owen, who didn’t appreciate his ferocity. Neither did the fans, who saw Medwick’s slide as a rub-it-in moment with the Cardinals up late, 8-0. When Medwick returned to his defensive post in left field the next inning, he became the target of an overflow of fans in the big new bleachers, fans who just happened to have a lot of fruit on them. The scene immediately proved two things: That the fans were angry, and they ate healthy. Medwick tried to ignore the throng, and Tigers officials and police tried their best to placate the crowd, but finally it was decided that it was best for everyone if Medwick left the game. Which he did. Reluctantly.

For the 1934 World Series, a massive bleacher section was erected behind left field seating nearly 17,000 fans. It was completely removed after 1935 to allow for the expansion and enclosure of the main structure.

That Second Deck Stole My Ball!

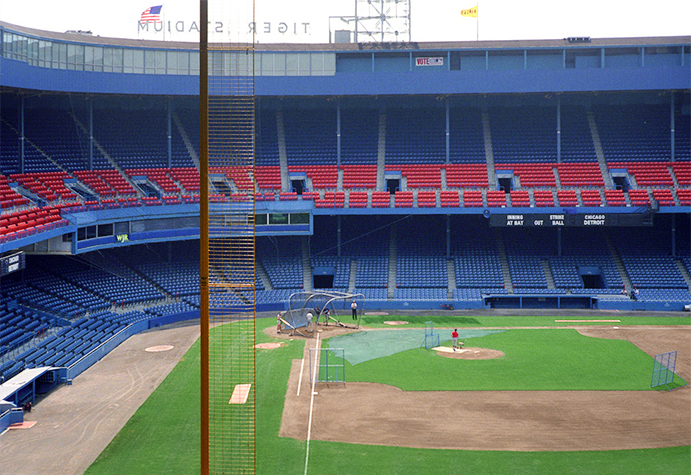

The next and last major expansion at The Corner, during the late 1930s, was a multi-year process that resulted in more aesthetic harmony. The two-level grandstand, and the press box atop it, was extended around the right-field corner; soon after, the left field bleachers were torn down and the main structure extended to completely encircle the field. The only area left uncovered was the upper deck of the center-field bleachers, which was backed by an enormous new scoreboard. Capacity was now over 50,000.

The architects’ biggest challenge with this latest addition was how they were going to seamlessly extend the ballpark behind right field without pushing back Trumbull Avenue; it was one thing to do that with Cherry Street, but busy Trumbull wasn’t exactly a back alley. The solution was most interesting. The Tigers clipped the number of rows on the lower deck but extended the upper level above the outside sidewalk, right up to the edge of Trumbull’s gutter. Similarly, the upper deck was positioned over the right field warning track, a full 10 feet closer to home than the outfield fence below. This made life difficult for outfielders who squared up on the track and hoped that the upper level wouldn’t steal a deep high fly for a home run—or ricochet off the above facing, making them chase the caromed ball back toward the infield.

The newly built outfield bleachers, encroaching into the field, turned the venue into a hitter’s park. Though while straightaway center remained a solid poke, officially at 440 feet—later measurements revealed that it was unofficially 425—the gaps were within easy reach at 365 (left) and 370 (right), and the right field line ended a mere 325 feet from home plate—315 if you were counting to the front of the overlapping upper deck. On a rare occasion, the Tigers tried to neuter the cheap shots into the right field seats by placing a screen between the first and second decks.

The close proximity of the upper deck roof made an enticing target for tape-measure sluggers to wow the crowd. A 20-year-old Ted Williams, in just his ninth major league game, was the first to mash a ball completely out of the enclosed ballpark in 1939—the first of some 30 monster shots that either hit onto or over the roof. Norm Cash, who called Tiger Stadium home for 15 years, did it four times. Mickey Mantle, who played far fewer times at The Corner, did it three times, including one poke that was sent an astronomical 643 feet—a figure that, if true, was ever longer than Babe Ruth’s titanic 1926 blast. Only four roof-toppers were sent to left field, all of them by names you would expect: Harmon Killebrew, Frank Howard, Cecil Fielder and Mark McGwire.

The most famous moonshot at Tiger Stadium took place in the 1971 All-Star Game when Reggie Jackson parked one at the base of a light standard atop the right-center field roof before 53,000 in attendance and 30 million more watching on NBC. A typically boastful Jackson told reporters after the game, “I didn’t travel 2,000 miles to strike out.”

Few hitters owned The Corner more than Hank Greenberg. The lanky, athletic Tigers slugger put up home splits that could have been easily confused for an entire season’s worth of numbers. In 1934, Greenberg hit 41 of his 63 doubles at Navin Field; in 1937, he knocked in 101 runs just at home. And a year after that, 39 of his career-high 58 homers were belted in Detroit, establishing a still-standing season record for the most home runs hit by a player in one ballpark. During a 17-year span for the Tigers constantly interrupted by injury and war duty, Greenberg hit .343 at home and averaged over one RBI per game.

The entry “house” where fans entered circa 1940. It would be rebuilt over a decade later as something more rectangular and industrial in shape. (Detroit Public Library—Burton Historical Collection)

Puttin’ on the Briggs.

Navin Field’s final expansion was overseen by Walter Briggs, who assumed control of the Tigers following Frank Navin’s death late in 1935, just weeks after the Tigers finally won their first World Series for him. A more charismatic individual than the taciturn Navin, Briggs renamed the ballpark after himself and added a few new wrinkles previously unseen in the majors; he installed underground sprinkler systems, placed auxiliary scoreboards near the infield for those whose necks had gotten sore turning their heads toward the main center field board, and utilized tarps to protect the infield from wet weather. It continued a tradition of ballpark firsts Navin had earlier instituted, such as the first dark backdrop for batters behind center field. Briggs would also eventually tear down the entry house at The Corner and replace it with a square-shaped building, a far less charming façade more in line with the main ballpark bowl; it might have been confused for supervisors’ quarters in front of the larger auto factory.

One modern trend Briggs continuously resisted was night baseball, preferring the tradition of playing under the sun. He finally relented in 1948 when Briggs Stadium became the last AL park to install lights. Eight standards of various sizes—some of them so massive as to seemingly overwhelm the environs below—hung close atop the roof and undoubtedly changed the ballpark’s character both for fans inside and passers-by outside. Night games initially became a financial salvation for the Tigers, as far bigger crowds showed up under the lights.

Enclosing the ballpark with increased capacity lured other events to The Corner. Tiger Stadium’s other main tenant, football’s Detroit Lions, was not the first gridiron outfit to call the place home. A football namesake of the Tigers used Navin Field in 1921 as part of the American Professional Football Association, a brief forerunner of the National Football League born a year later. Next at Navin Field came the Detroit Panthers, the NFL’s first—and short, lasting two years—foray into the Motor City. The Lions came to Detroit in 1934 from micro-small market Portsmouth, Ohio (population, 43,000) but didn’t play at The Corner until after its expansion to 50,000 seats in 1938. Tiger Stadium may have had a reputation for intimacy among baseball fans, but the Lions hardly felt the same vibe; chalking up a rectangular-shaped football field on a square plot of grass meant expansive, wasted sideline space. There were no pullout seats to bring the fans closer, and no temporary bleachers were ever constructed on the grass. The Lions chose to make fans on the third-base side the lucky ones—pitching the field closer to them, at the expense of those with 50-yard line seats on the other side, baseball’s right field bleachers, which were 40 yards or more from the near sideline.

A diversity of other events was held at Navin/Briggs/Tiger Stadium over its 88 years of existence. Concerts were a natural, with acts as varied as Nat King Cole, the Eagles and Perry Como. South African activist/parolee/future president Nelson Mandela brought his freedom tour to Tiger Stadium in 1990, drawing 49,000 enthusiastic supporters. Jehovah’s Witnesses rented the joint for a day in 1970. Legendary boxer Joe Louis successfully defended his heavyweight title in 1939, though the Tigers eventually soured on boxing because of the wear-and-tear of the playing field from ringside fans. Even opera was given a shot in the 1930s, but low turnouts confirmed that ballpark patrons preferred RBIs over arias.

“Take Him to Detroit!”

As the years began to roll by and middle age began to beset Tiger Stadium—as it would finally be referred to starting in 1961 after John Fetzer bought the team—the volume started cranking up from people complaining of its shortcomings. Chief among them was the lack of convenient parking, as the Tigers never owned or operated any lots with the exception of a private area for players and employees, tucked away near the main entry at Michigan and Trumbull. Fans had to settle for precious few private lots near the ballpark, street parking or the front yards of many neighborhood houses—if allowed by its owners.

To maximize minimal space with Trumbull Avenue close behind right field, the second deck stuck out 10 feet over the warning track—making life interesting on occasion for the right fielder. (Wikimedia—Csh00w)

Relievers had it worse. They were stuck in Tiger Stadium’s bullpens, sarcastically referred to as “submarines” because they were sunk so low that players could barely see the field at eye level through a vertically short slat of fencing. The Tigers never spent the money for a periscope to help these guys get a better view of the action.

There was a more unnerving issue: Detroit itself. The city hit its population apex in 1950 with nearly two million residents, but from there everything gradually went downhill. Heady competition from Japan and Europe weakened Detroit‘s monopolistic grip on worldwide auto production. Increased automation at production plants further curtailed the workforce. Whites fled to the suburbs, and blacks who hoped to follow and had the means to do so were often stiff-armed, leaving them incarcerated in a city that was slowly but surely turning lower class. Race riots in 1967 only accelerated the decay, and Detroit’s danger factor became a sick national joke. In the 1977 spoof flick Kentucky Fried Movie, a brutal Asian warlord drives a headstrong prisoner into hysterical fear when the guards are told to “take him to Detroit.” Major leaguers visiting the Motor City understood the reputation all too well; it was one of the few cities in which they seldom left the hotel for an evening out.

It wasn’t long before the city’s problems infiltrated Tiger Stadium. Every night became Hell Night for visiting outfielders, who were viciously heckled and peppered with bottles and batteries from the bleachers; some didn’t even bother to go and out and warm up between innings, waiting in the dugout until the first batter stepped into the box. By 1980, things got so out of hand that the Tigers closed off the bleachers and didn’t reopen them until stronger security measures were put in place.

Detroit’s widespread physical and civil decay was a shame, because it paralleled some of baseball’s great moments at Tiger Stadium. The 1968 team, behind Denny McLain’s 31 wins, outlasted a tough St. Louis Cardinals team in a seven-game World Series to gain revenge for their heated Series loss in 1934. There was the one magical summer of Mark Fidrych, an oddball with curly blonde locks who became the talk of baseball in 1976 with his penchant of talking to baseballs, grooming the mound and stifling opponents (19 wins, nine losses and an AL-best 2.34 earned run average) before persistent arm troubles ruined his career. And there was the glorious 1984 “Bless You Boys” campaign of manager Sparky Anderson, rugged slugger Kirk Gibson and workhorse ace Jack Morris forging the Tigers out to a remarkable 35-5 start before coasting to their third world title—but, alas, also triggering post-Series riots around the ballpark resulting in one death, 82 injuries and 41 arrests.

Tiger Stadium’s green seats, along with the rest of the ballpark’s interior, were painted a deep sky blue in the late 1970s; orange seats were also installed to break up the monotony of color. (Jerry Reuss)

The Tiger With Nine Lives.

For the latter half of its existence, Tiger Stadium held its ground while politicians and the team alternately took turns looking at possible replacements.

After World War II, Detroit tried seven straight times to secure the Summer Olympics—and failed each time, finishing as close as a runner-up (by one vote) to Mexico City in 1968. As the Olympic dream vanished, so did the likelihood of the Tigers moving into a post-Olympics Olympic Stadium.

Tiger Stadium came closest to an early extinction in 1972 when Wayne County proposed a sparkling $126 million domed stadium southwest of downtown, alongside the Detroit River. The Tigers went so far as to sign a 40-year lease, but a few curious citizens took a closer look at the stadium deal and discovered, cleverly hidden amid the legalese, a provision that put taxpayers on the hook for any cost overruns. This got the ear of the courts, which ruled against the project and killed it.

Next came the Detroit suburb of Pontiac, 20 miles to the north, which was also trying to court both the Tigers and Lions to its own domed stadium project as approved by the state. But Tigers owner John Fetzer, fueled with a sudden change of heart, didn’t want any part of it—saying that the Tigers not only belonged in Detroit, but at Tiger Stadium. The Pontiac Silverdome would become reality as a football-only venue hosting the Lions, who would play their final game at The Corner in 1974.

Fetzer’s newfound case of nostalgia over Tiger Stadium wasn’t blinded by ignorance. He knew that the joint, in the words of longtime Tigers general manager Jim Campbell, was “in reasonably good shape but underneath is getting very tired.” It was also getting very hot in places, such as the press box—gutted out by a fire in the winter of 1977. The Tigers had even stopped Bat Day as a promotion—not out of fear that raucous fans would start killing each other, but because the team worried that the banging of the bats could potentially weaken the ballpark’s infrastructure. So Fetzer sold the ballpark to the city for a single dollar—and in exchange, the city would spend $15 million to spruce up the place.

Over the next five years, the interior and all seats were repainted with a deep sky blue, with the exception of lower seats in the upper deck lathered in orange; the new plastic seats were also wider, decreasing capacity for the sake of increased American buttocks. A new broadcast booth was attached to the bottom of the second deck, giving play-by-play announcers an impeccably close view of the action just 80 feet from home plate—though it also tested their reflexes when a foul ball came screaming back at them. Outside, aluminum siding was placed on the exterior walls to reduce the annual cost of repainting. Other planned improvements, most notably the addition of luxury boxes, didn’t make the cut due to budget restraints.

Fetzer sold the Tigers in 1983 to Domino’s Pizza kingpin Tom Monaghan, who publicly stayed the course in declaring that the team would remain at Tiger Stadium. But he had second thoughts when witnessing the oxymoronic “celebration riots” that followed the Tigers’ 1984 World Series triumph. Eventually he began looking to leave as well. He imagined a new ballpark on the other side of I-75 with retail shops and even a nine-hole golf course, all surrounded by parking lots, meaning it would have been less an absorbent to the community and more its own island, a Xanadu among scarred, lower-class neighborhoods. The Tigers may have liked the idea, but no one else did.

Looking down Tiger Stadium’s right-field line toward home plate. Note the close proximity of the broadcast booth (hung under the second deck) to home plate. (Jerry Reuss)

Give Your Ballpark a Hug.

Increased chatter of a possible new ballpark alarmed fans loyal to Tiger Stadium. Four of them decided to do something about it, meeting at a Domino’s (of all places) and establishing the Tiger Stadium Fan Club. From its grass roots beginnings, the club eventually grew to 11,000 members and played the role of the pesky fly trying to make its point while the Tigers reached for the swatter. Some of the club’s actions were symbolic; twice, it performed a “hug” of Tiger Stadium by getting enough supporters to show up, hold hands and encircle the ballpark. Other actions carried more substance; it lobbied city government to enact legislation barring public funds being used toward a new ballpark, and helped get Tiger Stadium named as a national historic landmark, meaning federal dollars could not be used to tear it down.

The Tiger Stadium Fan Club also laid out its own idea of how to renovate the aging yard. With the help of architect John Davids—who designed Tom Monaghan’s private box at Tiger Stadium—it came up with the Cochrane Plan, which called for a petite third level, luxury boxes, expanded administrative offices and clubhouses, and a Tigers Hall of Fame. The Plan’s $26 million estimate seemed too rosy to many, but it didn’t matter to the Tigers—who, like most multimillion-dollar sports businesses, wasn’t going to tolerate outside tips from the “little people.”

After 10 years, Monaghan gave up and let another local pizza impresario, Little Caesar’s Mike Ilitch, take a crack at owning the team. Like Monaghan, Ilitch initially did all he could to embrace Tiger Stadium—or, better put, to profit as best he could. He dolled up the interior with advertisements wherever he could put them—on the upper-deck facings, the backstop wall, even the numerous support posts that had long obscured a complete view for some fans; maybe those unlucky patrons couldn’t see the whole field, but they sure knew where to find a good doctor. Outside, the Tigers rethought the main entry plaza at Michigan and Trumbull, creating a storefront extension at street level called “Tiger Plaza” that included food and souvenir shops.

Ilitch proved to be a more positive alternative for Tigers fans, and he certainly scored points when he brought back beloved Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell, inexplicably dumped by Monaghan a year earlier. But from a business point of view, Ilitch eventually grew to realize that Tiger Stadium just couldn’t hold its own financially. Baltimore, Cleveland and Arlington, Texas had all opened up beautiful new ballparks rich in revenue streams, and more major league teams were looking to follow suit. Ilitch knew that he if he didn’t go with the flow, he would find competing at Tiger Stadium increasingly difficult. Late in 1995, he persuaded both the City of Detroit and the State of Michigan to make a critical decision: Overturning the 1992 ordinance barring public money from being spent on a new ballpark.

There was only so much the Tiger Stadium Fan Club could do. But it tried. The group collected enough signatures to put the ballpark funding repeal to a vote, and depression set in when a whopping 80% of the Detroit electorate disagreed. Badly defeated, the club gave it one last shot in court, but on July 5, 1996—barely 100 years since the birth of baseball at The Corner—the Michigan Court of Appeals denied the motion, giving Detroit and the Tigers the green light to move forward with what would become Comerica Park in downtown.

The Tigers’ remaining years at Tiger Stadium played as seriocomedy. Detroit struggled to win but remained entertaining, as the steroid era met the ballpark’s cozy dimensions with predictable results. On May 28, 1995, a dozen fly balls cleared the fences between the Tigers and Chicago White Sox, setting a major league record. A year later, a Tiger Stadium-record 230 home runs were smashed—130 of them surrendered by an atrocious Detroit pitching staff that produced a 6.38 ERA, the worst in AL history. The home run record was reset to 235 three years later, during the Tigers’ final campaign at Tiger Stadium.

There were moments of joy to behold down the stretch. The advent of interleague play made for some nostalgic pairings between the Tigers and World Series foes of the past, as the Cardinals, Cubs and Cincinnati Reds all made their first—and last—regular season visits to Tiger Stadium, bringing out large crowds in every case. In 1994, a cool round number was reached when Tiger Stadium’s 100 millionth fan clicked through the turnstiles. And in the Tigers’ final contest at The Corner on September 27, 1999, Detroit designated hitter Robert Fick turned a close game into a rout with the ballpark’s last hit—an eighth-inning grand slam that reached the rooftop—to give the Tigers an 8-2 victory over the Kansas City Royals. Fick’s shot gave Tiger Stadium a grand total of 11,111 home runs.

Tickets for the final game had sold out just 33 minutes after they went on sale. Over 800 press credentials were okayed. One was for Nightline anchor Ted Koppel, who did his ABC late-night news show from home plate. Fans wistfully walked through the joint one last time, happily tolerating the cramped, catacomb-like concourses, grimy bathrooms and long concession lines. When, after the game, home plate was removed and shown being placed eight blocks away at Comerica Park, the crowd booed. Ernie Harwell, 81 years young and still active in the Tigers’ booth, gave the final word to the fans. “We love nostalgia, we love history and we like to be sentimental. But I think you have to have a degree of practicality. We just have to keep (Tiger Stadium) a treasure in our minds.” The ceremonial last pitch was delivered by the great-nephew of Charlie Bennett, who threw out the first in 1896. In a sense, The Corner had come full circle.

September 27, 1999: Detroit’s Todd Jones strikes out Kansas City’s Carlos Beltran to close out Tiger Stadium’s 88th and final year as a major league ballpark. (Flickr—Aaron Webb)

Tiger Stadium was not immediately torn down, as politicians argued what to do with the ballpark—or what not to do with it. Meanwhile, there was activity at The Corner as the Tigers moved on to Comerica Park. In 2000, HBO came out and dressed the ballpark up to look like old Yankee Stadium—with CGI filling in the unwanted background bits—for the movie 61*, produced by Billy Crystal. A few more events followed, including a contest between two summer college league teams on July 24, 2001—the intent being to lure an independent minor league team to Tiger Stadium. A crowd of 1,500 showed, and a youngster by the name of Peter Varon smoked a line shot that ricocheted off the facing of the upper deck in right. It would be the last homer ever seen at The Corner.

Shortly thereafter, Tiger Stadium became just another abandoned Detroit relic. Only the rust ruled. There were no upgrades. No maintenance. No demolition. Nothing. Everybody had their ideas, good ideas. Many of them were focused on rehabbing the joint with retail, housing and recreation, leaving the playing field intact for future use. The hope was that any of these schemes would spark a chain reaction of urban renewal and pep up Corktown. Stubbornly, the City of Detroit stood mute on the subject. Then there was Tigers owner Mike Ilitch, who per the agreement to build Comerica Park would be given $500,000 a year to provide maintenance to Tiger Stadium while it stood vacant. But local reporters discovered that he likely pocketed most of the money, leaving the ballpark to continue its rot.

The Shape of Things to Come: Renditions for a youth sports facility (left) that will surround the Tiger Stadium field which still exists, and a mixed-use development (right) with a main entry at Michigan and Trumbull. (Detroit Economic Growth Corporation; Rossetti)

In the summer of 2008, the demolition crew finally showed up and tore everything down except for the portion of the ballpark between first and third. Preservationists put up a fight to save what was left of it, but a year later it, too, was razed—turning Tiger Stadium into a ballfield without a structure around it.

Finally, in the mid-2010s, something was done. The Detroit Police Athletic League raised enough money to build a youth sports facility on the site. The field would be retained, and there would be homage to the Tigers’ past; yes, even the flagpole would remain. Accompanying the facility at Michigan and Trumbull would be the mixed-use development people had been talking about for years, a four-story structure that would stretch down Michigan and include a row of new housing units down Trumbull, behind the still-existent right field.

Tiger Stadium didn’t survive the link to the rebirth, but it survives in spirit—indeed a treasure in the minds of the millions who experienced one of baseball’s great and endearing ballparks.

The Ballparks: Comerica Park For over 100 years, the crossroads of Cochrane and Michigan Avenues served as the cornerstone of Detroit baseball, with legendary names as Cobb, Greenberg, Kaline, McLain and Fidrych gracing famous episodes and careers upon Tiger Stadium. Now, closer to downtown, the Tigers’ new home at Comerica Park stands as a virtual modern museum for fans young and old—and a place where the ghosts of Tigers past can comfortably feel at home and watch the future take shape.

The Ballparks: Comerica Park For over 100 years, the crossroads of Cochrane and Michigan Avenues served as the cornerstone of Detroit baseball, with legendary names as Cobb, Greenberg, Kaline, McLain and Fidrych gracing famous episodes and careers upon Tiger Stadium. Now, closer to downtown, the Tigers’ new home at Comerica Park stands as a virtual modern museum for fans young and old—and a place where the ghosts of Tigers past can comfortably feel at home and watch the future take shape.

Detroit Tigers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Tigers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.