The Ballparks

Veterans Stadium

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs

The centerpiece of the City of Brotherly Love’s sports hub, Veterans Stadium was a civilized structure filled with uncivilized spectators, where Phillies prevailed, Eagles soared and cats and rats ruled the underbelly. Though it wore out its welcome as fast as its many carpets, the Vet helped catapult the Philly sports scene into modern times and proved that no facility, however stately, could tame the city’s famed bullies and boobirds.

When a family moves from an old, rotting house to a fancy new home, there is a natural inclination that it will better respect and behave within its new environs as dedicated caretakers, trying to avoid those first dings, dents and scratches and becoming better residents for it.

The Philadelphia Phillies served as the model for this type of evolution when they moved from decrepit Connie Mack Stadium (nee Shibe Park) into behemoth, modern Veterans Stadium in 1971. The Phillies seldom were a good team before their relocation to “The Vet,” and they weren’t necessarily a juggernaut afterward—recording just 13 winning records in 33 years based there. But there was a sense of “can do” after all the years of “can’t do” back at the old park, as pride of place and a corporate refresh undergone brought an adapted attitude that unchained the Phillies from the defeatist mindset of previous eras.

While the owners played the good hosts within their new home, the houseguests were as rude as ever. The Vet failed to domesticate Philadelphia’s notorious boobirds, known for verbally abusing everyone from Richie Allen to Santa Claus. Fans of both the Phillies and football’s Eagles, the Vet’s two prime tenants, were as vicious as ever; the higher the level, the more savage they got. Stumbling into the highest level, the 700 Level, wearing the uniform of the enemy was an invitation to getting your head cracked like the Liberty Bell. Long after the Vet’s demise, the 700 Level continues to live in such infamy that a popular online sports blog is named after it.

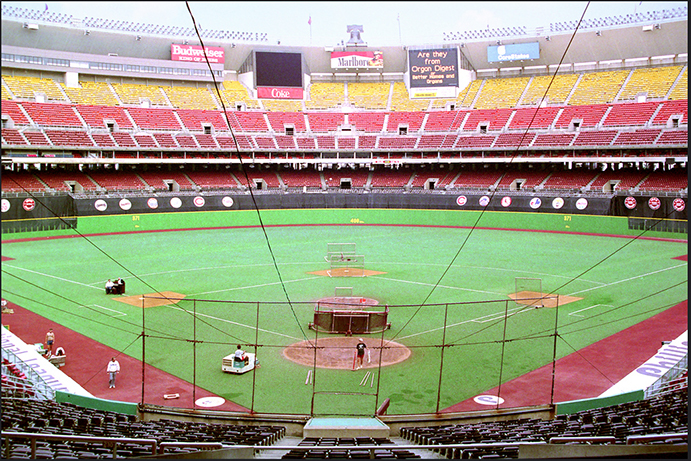

Carbon-based units aside, Veterans Stadium was purely typical of sports venues built in the 1960s and 1970s: An immense, fully enclosed multi-purpose stadium featuring fake turf with all the give of concrete, surrounded by a sea of parking. Richie Hebner, who played for the Phillies from 1977-78, provided the definitive statement on the Vet and its structural clones of the time when he admitted, “I stand at the plate in Philadelphia and I honestly don’t know whether I’m in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis or Philly.”

Veterans Stadium was passively praised when its doors opened for the first time—not so much because it was a grand architectural statement, but because everyone in town was relieved to be freed of the relic-stained past. Yet it was assailed at an exponential rate as the years quickly passed. Like all the other cookie cutter monsters of the period, the Vet was a compromise for sports teams sharing space consisting of completely different playing shapes, for which no one was completely happy. While it rescued Philadelphia sports from ancient times, the Vet forged a populace to pine for a future where baseball and football could, once again, be separated from one another.

Whack-a-Site.

Philadelphia was emblematic of American Northeast cities in the decade following World War II: Rotting, rusting and unable to contain white flight to the suburbs. Emerging cities to the west looked appealing to major league teams, themselves looking to escape from the archaic environment. The Boston Braves elevated that urge when they successfully relocated to Milwaukee and instantly became a smash hit in a new stadium.

Following the Braves’ lead, the Philadelphia Athletics bolted town after 1954 to Kansas City, leaving the Phillies as the city’s only baseball entertainment value. As a parting gift, the A’s sold Connie Mack Stadium to the Phillies, who wanted it like a hot potato—but they had no choice, given that any other buyer would possibly tear down and redevelop the property, leaving the National League team of 70 years homeless.

The city, worried that the Phillies might throw up their hands and depart westward as well, grew nervous enough to begin conceptualizing a new facility, either as a baseball-only venue for the Phillies or a multi-purpose stadium that would include the Eagles of the National Football League. What followed over the next 10 years would be a dizzying game of whack-a-site, with ideas for new stadium locations popping up here and there—only to be knocked down by someone in charge.

Initial thoughts focused on a 50,000-seat facility west of downtown in Fairmount Park, along the Schuylkill River; that would ultimately be vetoed by Philadelphia’s powerful planning commission board. A more ambitious idea to build a multi-purpose stadium on “stilts” over the railroad tracks at the Penn Railroad 30th Street station, as part of a larger development featuring an arena, hotel, retail and dining, was also rejected by the city because it couldn’t obtain Federal subsidies required in the budget. On the northeast end of Philadelphia, along the Delaware River, another ballpark plan consisting of an adjacent theme park, marina and bird refuge was also panned by the planning commission (albeit by a single vote) because of its wayward proximity and financial issues. Other proposed sites, including a number of country clubs with expansive land to offer, barely got past the conversation stage.

Phillies owner Robert Carpenter dreamt up his own idea of building a ballpark across the river in New Jersey, on land he recently purchased in Delaware Township near Camden. Local officials loved the idea, while those back in Philadelphia grew so worried that they lobbied the state to overturn the ban on selling alcohol at Connie Mack Stadium as a carrot stick for Carpenter to remain. But township residents rose up against the idea, worried over increased taxes, disruption of a quiet lifestyle and because the potential consumption of beer by Phillies fans alarmed them. A statement from a local church group asked: “Can you imagine what will happen when this group of beer drinkers pours onto the highways of Delaware Township and Camden County?”

With virtually all site options exhausted by bureaucrats and naysayers, the city focused on one plot of land that seemed to make the most sense all along: A spacious site at the city’s south end alongside the massive 100,000-seat Municipal (later JFK) Stadium, the neutral host of the prestigious Army-Navy college football game. There would have to be some buying out of private property to make the space available—leading to the inevitable haggling between buyer and seller over the value of the land—while the city had to twist the arms of the Eagles, hardly desperate to leave its current home at the 70,000-seat, football-friendly Franklin Field on the University of Pennsylvania campus. By the end of 1964, the city felt comfortable enough to put the stadium site up to a public vote; a 55% majority okayed a $25 million bond measure to get things started.

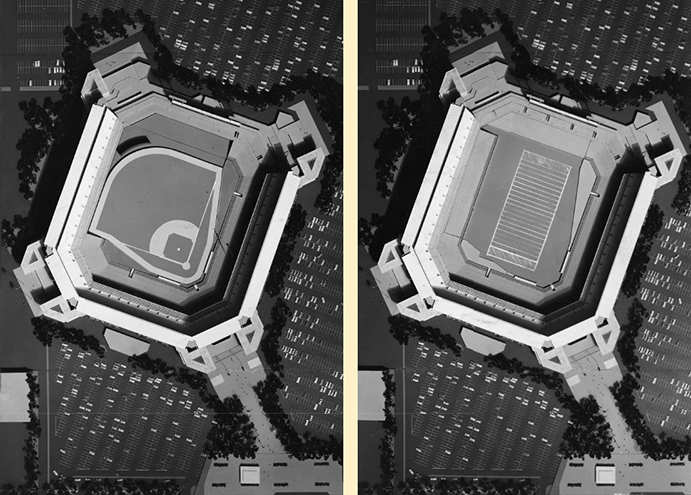

The original model for Veterans Stadium shows something completely different from the final product; a horizontal structure with beveled corners, similar to the future Joe Robbie/Hard Rock Stadium in Miami. Nobody liked it. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

Into the Octorad.

Two local architectural firms, George M. Ewing Co. and Stonorov and Haws, were hired by the city to come up with a stadium design that could work for both the Phillies and Eagles. Among the architects’ initial ideas was to build both a subway station and parking garage into the structure itself to reduce walking time to the seats. One year and more money than the city had budgeted later, the first model was revealed; no one was happy with it. Looking like the future Joe Robbie/Hard Rock Stadium in Miami, the rectangular structure diagonally beveled at each corner was so disliked by the Phillies that they refused to sign any new lease and, with its current lease at Connie Mack Stadium soon expiring—and the ballpark’s new owners whom the team sold it to anxious to tear it down—Robert Carpenter began to publicly muse New Jersey all over again.

The city listened and went back to the drawing board. Two new architects were brought in; Ronald Knabb Jr., another local designer, and Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Hugh Stubbins, whose portfolio was heavy in educational projects. For this new round of designs, the Phillies and Eagles were more actively involved; despite the extra cooks in the kitchen, the process became smoother and more amicable. It was here that the true Veterans Stadium began to take shape, with an outer contour that was neither rectangular nor circular—but something in between. Knabb, who came up with the design, lovingly referred to it as octorad. He later explained: “’Octo’ is Latin for numeral eight. ‘Rad’ is short for radius. There are eight points of radius on a circle. Connect them with straight lines of chords, and you have the shape of the stadium.”

From the outside, the Vet had a contemporary, almost stately appeal. Vertical concrete supports, spaced out 30 feet from one another, gave the exterior a confident grace, visually complementing a fluid, consistent pattern of spectator ramps; the supports also worked to hold a small overhang encircling the stadium’s upper deck, topped by a ring of lights as opposed to overbearing towers of bulbs.

The outer plaza which spectators accessed to enter the Vet was equally harmonious as it was functional. Fans walked up one of eight semi-circular walkways that rose to a main walkway rimming the base of the stadium, above a moat of parking for players, staff and service vehicles. They then entered at the top of the lower deck, allowing easy access regardless of whether their seats were on the field level or high up in the rough-and-tumble 700s. The Sporting News took note of the Vet’s coordinated geometry and concluded that the venue is “the model stadium if a mathematician became baseball commissioner.”

Even before the first shovel was plunged into the ground, costs on the Vet began to spiral out of control, as the city was criticized for overpaying the (multiple) architects and engineers. Hugh Stubbins, by now the lead designer, eliminated some of the bells and whistles initially associated with the Vet to reduce the projected budget. Definitely out was the idea of a dome that would have added 50% to the total cost. Despite all of the cutbacks, the city had to perform the embarrassing duty of going back to the voters and asking for another $13 million through a second bond measure in the spring of 1967. It passed, but not without inducing sweat; the tally was 50.8-49.2%.

The Name Game.

No one thought that the Vet’s ballooning cost would take a back seat to a somehow bigger controversy: What to name it.

Two camps of thought emerged. A conservative wing embraced military options such as Eisenhower Stadium (named after the former President and World War II general) and War Veterans Memorial Stadium, which led city councilman John Kelly Jr.—the father of actress/princess Grace Kelly—to cringe. “Too many people already think of Philadelphia as a cemetery with lights,” he said. On the other end, there were those looking for a more lighthearted and provincial tone; the top choice among local residents and columnists was the Philadium, while others with a deeper, National Lampoon-ish sense of humor suggested titles such as Losers’ Paradise, the Topless Terrace (because it had no dome) and Swamp Hollow, because the Vet was built on a former swamp. Anything but “death, war and politics,” opined Lou Schienfeld, an exec helping to build a next-door arena with a cool name (the Spectrum), no public funding and a faster shovel-to-open door timeframe (18 months, as opposed to the Vet’s 42).

As the Battle of the Brand raged, city controller Thomas Gola had a novel thought: Put the name up for sale and bring in anywhere from $10-30 million to help pay for the stadium. The Campbell Soup Bowl, for instance. Gola’s idea was ahead of its time—and too soon, apparently, to make any headway.

In the end, the hawks won. On March 12, 1970, the City Council officially named the facility as Veterans Stadium—dedicated, as the plaque would later state, “to those brave men and women of Philadelphia who served in defense of their country.”

Inside the Vet’s façade lay a menagerie of concrete beams, ramps and concourses. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

A Welcome Overhaul.

Philadelphia had hoped for a 1970 opening for the Vet, but a construction strike and a bribery scandal involving the stadium manager pushed it back a year. A formal dedication took place on April 4, 1971 before 36,832 folks who, after watching the exterior build up, finally got a chance to check out the interior. To their pleasant surprise, what they saw contained far more character than the noble yet gray façade outside.

The plastic seats were arranged in an array of warm colors; brown on the field level, red in the lower upper-deck seats and bleachers, orange halfway up and yellow for the dreaded 700 Level; Phillies tickets purchased by fans matched the seat color they would sit in. Sixty concession stands were also coded via a bright color palette; the usual ballpark perishables—hotdogs, soda, beer, peanuts, popcorn—were sold at booths bathed in orange, more relative high-end items such as hamburgers, pizza, roast beef sandwiches and fried chicken were sold at yellow booths, and the blue booths were where you’d find the ice cream.

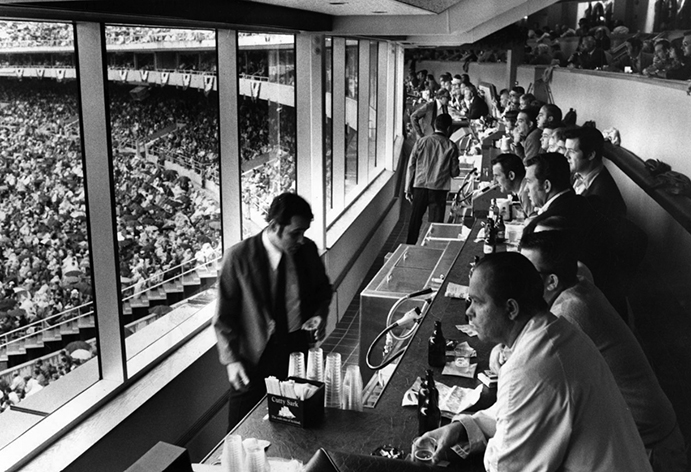

Those not content with ordinary seats had their own options. The Phillies requested, and got, 28 modern suites tucked in below the upper deck, and a lavish stadium club was situated alongside them, with a 200-foot-long bar and seating for 500 patrons—all looking straight out onto the field.

Additional panache was added in the outfield. There was a water fountain display behind the outfield fence—beating Kansas City’s Royals/Kauffman Stadium to the punch by a couple of years. A replica of the Liberty Bell was placed in straightaway center at the base of the upper deck; it would later be moved up to the top, separating a pair of new scoreboards. And surrounding the bell, initially, were a charming pair of mascots in Phil and Phyllis, two animatronic figures dressed in colonial garb that could have been confused as rejects from It’s a Small World. The loveable pair was disconnected by the end of the 1970s, turned into costumed humans that produced yawns from the kids and mean-spirited chuckles (at a minimum) from those with a 700 Level mindset. The Philly Phanatic would soon place Phil and Phyllis well back in the rearview mirror.

Six days after the Vet’s formal dedication, the Phillies finally took the field for their first game at the new venue on a chilly, gusty day. Philadelphia-based talk show host Mike Douglas sang the National Anthem; the ceremonial first pitch was chucked out of a helicopter 150 below to back-up Phillies catcher Mike Ryan, who bobbled but hung on. (Starting catcher Tim McCarver wanted no part of the stunt and deferred to Ryan.) Future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Jim Bunning, back with the Phillies after four years, took the ball and pitched 7.1 sharp innings in a 4-1 victory over the Montreal Expos.

The Opening Day result, played before 55,352, would not be typical for the Phillies nor Bunning in 1971. Philadelphia finished last in the six-team NL Eastern Division with a 67-95 record, while Bunning won only two of eight decisions at the Vet after Opening Day with a rough 7.54 earned run average. If that wasn’t fuel enough for Bunning to call it a career, then the monster smash he gave up to the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Willie Stargell on June 25 certainly qualified. Stargell’s bomb soared halfway up the upper deck in right-center field, through an exit tunnel; the ball, given a traveling estimate of well over 500 feet, was never found. Eventually, a black-and-gold star with an “S” in the middle was painted atop the tunnel entrance to denote what many believe was the longest home run ever hit at the Vet—a surprising tribute given to a rival opponent.

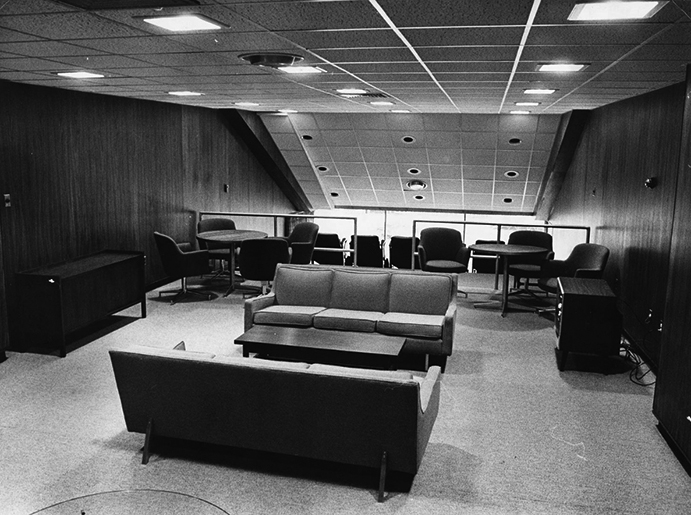

At the Phillies’ request, the city included 28 luxury suites below the Vet’s upper deck. This particular box was reserved for the mayor. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

From the front office to the clubhouse, the Phillies praised the Vet after years stuck at decaying Connie Mack Stadium. Cramped quarters in a rustic setting yielded to spacious vogue; Phillies pitcher Rick Wise joked to The Sporting News upon entering the Vet’s expansive clubhouse, “It’s a toll call if you want to talk to somebody on the other end.”

The opening of the Vet was more than a mere relocation for the Phillies; the team underwent a virtual makeover on multiple fronts. There was new blood on the roster (Greg Luzinski and Willie Montanez, with Mike Schmidt and Steve Carlton to follow), in the booth with first-year Phillies broadcaster Harry Kalas, and on the clothing rack with a new pinstriped jersey with a thick, soccer-style shoulder stripe and the introduction of the modern, swirling “P” team logo featuring a baseball cleverly entwined within the middle.

The Phillies also used the Vet as an opportunity to engender racial harmony in a city that bragged brotherly love. Back at Connie Mack Stadium, Phillies players dealt with a hostile fan experience, but African-Americans had it far worse. Maybe that’s why the Phillies were the last National League team, 10 years after Jackie Robinson’s debut in Brooklyn, to integrate; Richie Allen, the team’s first black star player, was run out of town after daring to challenge a white teammate (Frank Thomas) to a fight. Such trends not only hurt the Phillies’ reputation, but their place in the NL standings. With the opening of the modern, civic-built Vet, a more inclusive atmosphere emerged, reflected by the late 1970s with the presence of Dave Cash, Garry Maddox and Bake McBride; even Dick (nee Richie) Allen, who swore never to play in Philadelphia again, returned for a couple of years. And for what it was worth, the Vet organist routinely played the theme from Soul Train.

Of the many pregame and between-game stunts put on by the Phillies at the Vet during the 1970s under the wild creative mind of team exec Bill Giles, none went more hilariously wrong than Opening Day 1972 when a stunt glider named Kiteman crashed while racing down an upper-deck ramp. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

Sideshow Salmagundi.

To further offset the Vet’s sterility, the Phillies jazzed up the proceedings thanks to Bill Giles, the son of former NL President Warren Giles hired on by the team in 1969. Mike Ryan’s dizzying catch of the ball thrown out of a helicopter was just the first of many wild stunts intended to fire up Phillies fans—or leave them covering their eyes in anticipation of a stunt that could easily go awry. That was particularly the case in August 1972 when Giles invited famed high-wire legend Karl Wallenda to walk a tightrope high above the Vet’s artificial surface (with no safety net below) from one side of the upper deck to the other. Unbeknownst to Giles, the 67-year-old Wallenda drank three beers before the act but managed to complete the walk safely—even stopping at the halfway point to perform a headstand. Robert Gordon, who penned a book on the 1993 pennant-winning Phillies, wrote that it was the greatest high-wire act seen at the Vet until the arrival of closer Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams.

Not all of Giles’ stunts worked out as planned. On Opening Day 1972, a hang glider who went by the handle of Kiteman was to roll down a 100-foot wooden ramp on the upper deck and soar above the field to deliver the ball for the first pitch; but he lost his balance halfway down the ramp and crashed into the seats. (The crowd, naturally, booed.) In another wacky event between games of a doubleheader, local celebrities and ex-Phillies were conned into riding ostriches in a race around the field. One disc jockey failed the ostrich jockey test as she was thrown off the animal, which ran amok around the field—while another was spooked and took its rider (retired Phillie and future Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn) for the ride of his life.

Giles’ most famous creation was the Phillie Phanatic, which replaced Phil and Phyllis starting in 1978. Said to be discovered in the Galapagos Islands, the Phanatic was a big, green, furry lug with a horn-like snout, cartoon eyes and a rotund waist, clad only in a Phillies shirt and cap. Unlike Phil and Phyllis, the Phanatic had an attitude and, like the San Diego Chicken before it, playfully needled with opposing players and managers. The Phanatic’s favorite target was fiery Los Angeles Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, who was once stomped on in effigy—prompting the fiery skipper to burst out of the dugout and wrestle the Phanatic to the ground. It was all for show; the original man in the Phanatic suit, Dave Raymond, was a good friend of Lasorda’s.

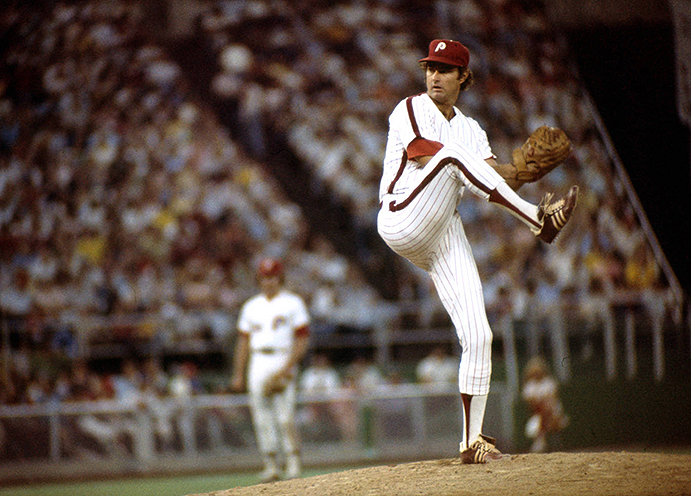

No one came close to winning more games at the Vet than Phillies Hall of Famer Steve Carlton, who recorded 138. He won 17 of those games alone in 1977, on the way to his second of four Cy Young awards. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

The Baby Bull, Lefty and Michael Jack.

Though the Phillies struggled in the first few years at the Vet, there was a strong sense that it was a matter of time before fortunes turned. The young talent on the field would vindicate that premise.

Outfielder Greg Luzinski, a classic pure-powered, lead-footed slugger, gave upper-deck fans hope of snagging one of his titanic homers; his most famous blast at the Vet occurred in 1972 when he struck the replica of the Liberty Bell at the base of the upper deck in straightaway center. Teammate Deron Johnson remarked, “It’s a good thing it wasn’t the real Liberty Bell—otherwise it would have a dent to go along with the crack.” Before the Vet’s first decade was completed, Luzinski registered three seasons with at least 30 home runs with 100 runs batted in.

The Phillies next struck gold in 1972 when they traded Rick Wise, their best pitcher, to the St. Louis Cardinals straight up for southpaw Steve Carlton. It seemed like an even deal at the time, and Wise would go on to have a decent rest of his career, winning 188 games over 18 seasons—but with the Phillies, Carlton’s trajectory would ascend him to the Hall of Fame. He particularly paid immediate dividends in Philadelphia during his first season as, somehow, he won 27 games for a Phillies team that finished 58-97. Of the 28 victories posted by the Phillies at the Vet that season—the fewest gathered up by the team in 33 years at the venue—exactly half (14) were recorded by Carlton, who won his first of four Cy Young Awards over an 11-year stretch.

A peculiar person to say the least, Carlton was one of those people you best approached with caution; reporters need not approach at all, as “Lefty” refused to speak to them. To keep the quirky Carlton happy—and retain his level of pitching brilliance—the Phillies set up a “blue room” adjacent to the team clubhouse in the Vet so that he could meditate before taking the mound. When the Phillies gave Carlton a special day after announcing his retirement in 1989, not only did he actually show up, but he (perhaps) showed a sense of humor by telling the fans, “I must take this time to say something about sportswriters. There will be silence for the next 10 minutes.”

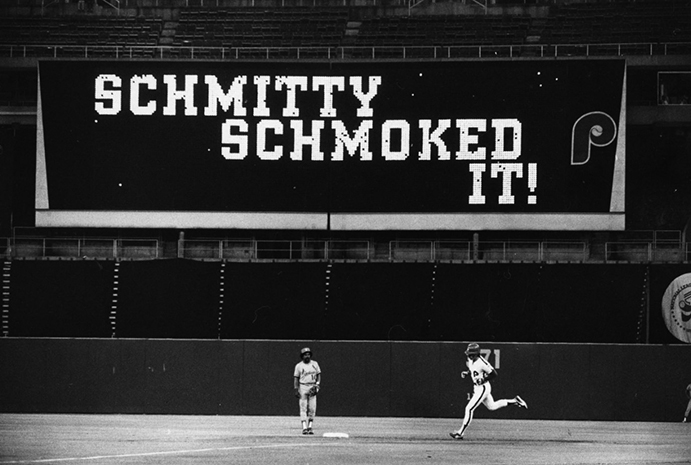

Carlton’s superstar equal at the plate would also evolve in the Vet’s early years. Mike Schmidt hit just .196 in his first full season of 1973, but completely turned it around the next year with his first of eight home run titles and 12 All-Star appearances at third base. As articulate and approachable as Carlton was quiet and reclusive, Schmidt would play all 18 of his seasons with the Phillies, racking up 548 homers, 10 Gold Gloves at third and three NL MVP awards.

Both Carlton and Schmidt dominate the leaderboards among those who played at the Vet. Carlton’s 138 victories at the stadium are far more than Curt Schilling, #2 on the list with 49. Schmidt’s 265 homers are double that of second-place Luzinski (130); Von Hayes is a distant third with 77.

With Luzinski, Carlton and Schmidt in prime form, the Phillies went from rags to riches as the 1970s progressed—bringing on esteemed veteranship in Pete Rose (who the Phillies signed in 1978), gifted outfielder Garry Maddox, punchy shortstop Larry Bowa and reliever/clubhouse favorite Tug McGraw. Over an eight-year period from 1976-83, the Phillies made six postseason appearances, won five divisional titles and two NL pennants. Attendance during this time surged, from the 1.5 million range to close to three million by the end of the 1970s.

It all came together in 1980, when the Phillies won their first world title in their 98-year history; Schmidt bashed a career-high 48 homers, Carlton won 24 games and became the last pitcher to date to log over 300 innings in a regular season, Rose led the NL with 42 doubles, Maddox earned a Gold Glove in center, and McGraw saved 20 games with a sterling 1.46 ERA.

The Vet opened with a 200-foot-long bar that served up to 500 patrons, with all seats facing the field. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

Tales From the 700 Level—and Beyond.

The clinching victory of that World Series, a 4-1 Game Six win over the Kansas City Royals before a mammoth crowd of 65,838, was accompanied by an overextended display of security and police as Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo didn’t want to take any chances with the notorious Philly sports fans who could potentially cause celebratory riots inside and outside the Vet. The excessive show of force was, fortunately, more show and less force as Phillies fans abided and rejoiced peacefully. This time, anyway.

It had been hoped that the Vet’s modern omnipresence would pacify Philadelphia’s infamously scornful sports fans. Maybe at first—but once the new stadium smell wore off, the fans returned to their nasty habits.

Throwing beer cups and hotdog wrappers onto the field wasn’t good enough for some Phillies fans. One threw a liquor bottle at Pittsburgh’s Al Oliver in 1976 and received a 60-day jail sentence for it. That same year, fellow Pirate Willie Stargell was the target of a bomb threat. Another Pirate, star outfielder Dave Parker, had a bullet thrown his way during a 1981 game. By 1986, even visiting players and fans were getting into the roguish Vet spirit; Cincinnati Reds pitcher John Denny beat up a Cincinnati Enquirer reporter, while later in the year fans of the visiting New York Mets went wild, doing damage to concessions stands and seats.

Getting the worst, most sustained treatment from Phillies fans at the Vet was outfielder J.D. Drew, who the Phillies failed to sign after selecting him second in the 1997 Amateur Draft as they offered only a quarter of the $10 million he and agent Scott Boras demanded. Two years later, Drew made his Vet debut—in the uniform of the Cardinals, one bearing someone else’s name as he was so petrified by the reaction he’d get. Drew’s deep concerns were confirmed; Phillies fans quickly figured who he was and booed him vociferously throughout, at times throwing batteries at him. The Phillie Phanatic chimed in, dumping two bags labeled with dollar signs onto the field between innings.

Sticking with tradition, Phillies fans refused to spare their own players from the wrath of angry catcalls. Even Mike Schmidt wasn’t immune; when the All-Star third baseman was in anything less than MVP form, the fans at the Vet let him know about it. Schmidt lamented about the verbal abuse during an off-year in 1978: “It got so bad, I didn’t want to go to the on-deck circle.” During another bad slide late in his career in 1985, Schmidt made headlines about how Phillies fans were a “mob scene…beyond help,” knowing full well that he’d get an angry earful when he appeared in his next game back at the Vet. So he took the field wearing a shoulder-length wig and racing glasses, leading some of the boos to turn to cheers; at least those fans appreciated Schmidt’s sense of humor, if not his honesty.

For all of their raucous, biting charm, Phillies fans had nothing on those of the Eagles—particularly as the Vet grew older. By the mid-1980s, the amount of drunken hostility among Eagles fans grew so disturbing that the team begged the NFL not to schedule late afternoon (4:00) games so that tailgating fans would have less time to get liquored up. A few years later, folks at the Vet got even more riled up by Eagles head coach Buddy Ryan, who harbored an intense hatred for the rival Dallas Cowboys as they came to Philadelphia for a late-season game. Played on a cold, snowy day, the Cowboys were mercilessly pelted by snowballs and a few other hardened objects to the point that the team banned liquor sales for the next two games; access to the 90 “penthouse suites,” recently added above the 700 Level to keep the Eagles from bolting to Phoenix, were all but boarded up to keep rowdy fans from breaking through and stealing alcohol available to suite patrons.

After an especially rowdy Monday night game at the Vet in 1997, the Eagles and the city decided to clear out a maintenance area under the stands and use it as an actual courtroom, with an actual judge, where quick justice would be meted out to those arrested above. When court adjourned for the first time, one fan was dragged in and accused of throwing a cup of ice on the field; he defended himself by placing the blame on his 10-year-old son. Another trying to rip off a toilet lid asked, after being charged, if he could take the seat home with him anyway. “Eagles Court” would continue after 1997, but it would be situated outside of the Vet.

Mike Schmidt rounds the bases after one of his 265 home runs hit at the Vet. Despite his Hall-of-Fame level of play, Schmidt absorbed a love-hate affair with Phillies fans who rode him whenever he failed to perform at peak MVP form. (Temple University Libraries, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs)

One Bad Rug After Another.

For the Vet to be configured from baseball to football, a portion of the lower deck along the third-base line was swiveled over left field, while extra seats hidden for baseball games were pulled out. All of this necessitated the use of artificial turf at the Vet; throughout its 33-year history, six different carpets were used, each costing between $1-2 million. They were all universally hated. “Worst field in the Western Hemisphere,” said The Sporting News’ Michael Kinsley in 1994. “Too bumpy for motocross.”

The original version of Vet turf was hard and fast, giving advantage to hitters—speedy ones at that. Later versions had more forgiveness, but there the usual side effects persisted—especially the rug burns suffered by fielders making diving catches.

The turf was especially hazardous for football players. This was excruciatingly exemplified in 1993 when Chicago Bears wide receiver Wendell Davis blew out both knees running a simple fly pattern, ending his football career at age 27. “My kneecaps were missing,” Davis recalled. “Then the doctors found them in my thighs.” Worried that his players could risk suffering the same fate, Eagles owner Norman Braman lobbied hard for either a safer brand of fake turf, or build a football-only stadium nearby with real grass.

When the last round of turf was planted at the Vet in 2001, the divots and cutouts that surrounded the baseball infield proved so hazardous for football players that a preseason game between the Eagles and Baltimore Ravens was cancelled shortly before kickoff. Some in the crowd of 45,000 became irate at the news, smashing windows at the will call booth.

This late 1980s view of the Vet reveals many of the stadium’s more notable features: The display of National League team logos above the outfield wall, twin scoreboards in the upper deck, and a replica of Philadelphia’s famed Liberty Bell at the very top. (Jerry Reuss)

You’re Going to Need a Bigger Band-Aid.

Beyond the constant updating of the fake turf, the Vet never underwent anything close to an overhaul—either a testament to its functionality or a reflection of the city’s inability to pony up money to provide upgrades. To the latter point, the city neared bankruptcy in 1990 and it was rumored that the Phillies would buy out the Vet. Though they ultimately did not, they still voluntarily pitched in for some needed fixing up.

Perhaps the most visible changes at the Vet were the installation of the football skyboxes atop the upper level in 1986 and, nine years later, the complete replacement of seats from the original Fall-like rainbow hues to a global deep blue. Capacity was constantly tinkered almost on a yearly basis, maxing out in 1985 with 66,744 seats. A much better (and brighter) lighting system was installed in 1988. Meanwhile, many of the Vet’s physical assets remained the same from start to finish, most ostensibly with the presence of all NL team logos above the outfield fence—the NL West in left field, and the NL East in right.

But the upkeep couldn’t keep pace with the Vet’s gradual deterioration. This was made loud and visually clear during the 1998 Army-Navy football game when a group of Naval cadets, standing over a field-level railing and mugging for the CBS camera, fell 12 feet to the turf as the railing gave way. Two of the cadets suffered serious injuries, including one with a broken neck.

David Montgomery, who took over as Phillies owner in 1997 after Bill Giles (who bought the team from the Carpenters in 1981) retired, publicly insisted that the Vet was never better than during its final 10 years of operation. But that didn’t gel with rumors that the Phillies were afraid to show the stadium to prospective free agents, or an ESPN poll that named the Vet as Major League Baseball’s worst venue. Even the players had started to turn on the stadium; perennial Phillies All-Star third baseman Scott Rolen called the Vet “a terrible place” with an atmosphere that was “just not good.”

Toward the end, the Vet grew increasingly popular with the cats and rats that dominated the stadium’s substructure and ducts. Football coach/broadcaster Jon Gruden, brought on as the Eagles’ offensive coordinator in 1995, recalls one of his first days on the job when, while working in the team offices at the Vet, a cat and two rats fell through the ceiling and crashed upon his desk.

An interior view of the Vet, shortly before the start of the Phillies’ last game played there on September 28, 2003. The original seats have been replaced by new blue ones, and the upper deck “penthouse suites,” added in 1986 to keep the football Eagles in town, rim the top. (Flickr—Paul Altobelli)

End Times at the Vet.

As the 21st Century dawned and it became apparent that multi-purpose stadiums were becoming an unwanted fad of the past, both the Phillies and Eagles began clamoring for separate new facilities to replace the Vet, each feeding their own interests. On December 30, 2000, they got their wish: Rather than throw nearly $100 million to prop up an aging Vet, the city approved side-by-side facilities for both teams, to open in 2004.

The Phillies played their final game at the Vet on September 28, 2003, bowing to the Atlanta Braves by a 5-2 count. No home runs were hit, meaning that the last official deep fly, hit the day before, was registered by Hall of Famer Jim Thome—playing his first of three seasons with the Phillies and giving him a stadium-record 28 for the season. Phillies dignitaries present at the final game included a rare appearance by Steve Carlton, an “air” home run from Mike Schmidt complete with a rounding of the bases, and an emotional finale featuring Tug McGraw, battling brain cancer, who recreated his victorious final pitch of the 1980 World Series. (McGraw lost his battle less than four months later.)

Three weeks before the Phillies played their first game next door at brand new Citizens Bank Park, the demolition button was pushed and the Vet came tumbling down. The stray cats did not suffer under the weight of the collapsing structure; they were gathered up beforehand and put up for adoption. Also collected in advance were all the seats; over 44,000 of them were sold to collectors.

Veterans Stadium rang up quite a bit of mileage over its one-third-century reign in Philadelphia. Besides the Phillies and Eagles, the Vet hosted over 100 concerts including many big names (Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, U2, Pink Floyd, Genesis, Paul McCartney, Madonna, Bon Jovi, etc.), 17 Army-Navy football games, college baseball tourneys featuring local schools such as Temple and Villanova, two pro soccer teams, a slow-pitch softball team, occasional appearances by minor league ballclubs, high school football, wrestling, Billy Graham, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

For the Phillies, the Vet represented an unmistakable quantum leap in their evolution. Before it, the Phillies rarely drew over a million fans. At the Vet, they averaged over two million per year, peaking in 1993 with 3,137,674 for an out-of-body, pennant winning campaign—their only winning season within a 14-year stretch from 1987-2000.

Say what you want about the multi-purpose, “cookie-cutter” stadiums that Richie Hebner famously couldn’t distinguish from one another; it allowed the Phillies to catapult from ancient times to a brave new world of mass fandom that has been smoothly leveraged to Citizens Bank Park, complete with the ghosts of the 700 Level. The Vet may have been bland, monstrous, and sterile, but the Phillies and their fans infused it with enough character to make it come alive.

In the build-up (or build-down) to the Vet’s March 2004 implosion, a worker poses with a graphic denoting the spot where the stadium’s longest home run—hit by the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Willie Stargell on June 25, 1971—landed in the upper deck behind right-center field. (Flickr—Andrew Evans)

The Ballparks: Baker Bowl It was a ballpark ahead of its time when built and well behind the times when abandoned 40 years later, by then a ridiculed dump given a slough of unpleasant names. Steel and concrete gave little comfort for the poor souls victimized in a series of unfortunate events—and as spectators covered their heads from debris, the right fielders covered theirs from the balls constantly ricocheting off the tall and cozily placed tin wall behind them. Welcome to Baker Bowl: Enter at your own risk.

The Ballparks: Baker Bowl It was a ballpark ahead of its time when built and well behind the times when abandoned 40 years later, by then a ridiculed dump given a slough of unpleasant names. Steel and concrete gave little comfort for the poor souls victimized in a series of unfortunate events—and as spectators covered their heads from debris, the right fielders covered theirs from the balls constantly ricocheting off the tall and cozily placed tin wall behind them. Welcome to Baker Bowl: Enter at your own risk.

The Ballparks: Shibe Park In baseball’s landscape of horse buggies and wooden carts, Shibe Park emerged as the Model T of ballparks, a sparkling trendsetter that introduced steel and concrete to the game’s vernacular, beget rooftop entrepreneurs long before Wrigley and brought the game out of its lumbered, fire-cursed squalor. That it stood for generations while two tenants largely stank up the joint was a testament to its perseverance.

The Ballparks: Shibe Park In baseball’s landscape of horse buggies and wooden carts, Shibe Park emerged as the Model T of ballparks, a sparkling trendsetter that introduced steel and concrete to the game’s vernacular, beget rooftop entrepreneurs long before Wrigley and brought the game out of its lumbered, fire-cursed squalor. That it stood for generations while two tenants largely stank up the joint was a testament to its perseverance.

Philadelphia Phillies Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Phillies, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.