THE BALLPARKS

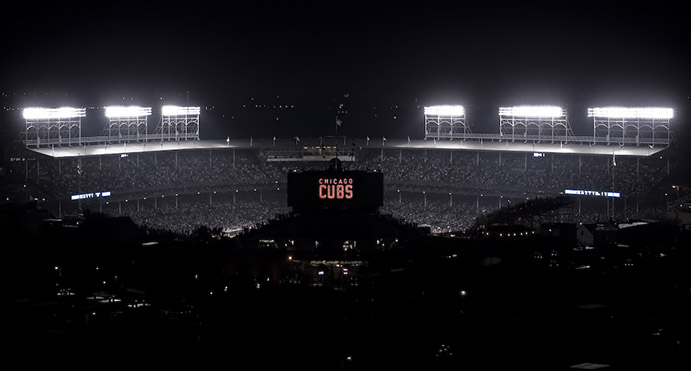

Wrigley Field

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

(iStock)

Nothing says community more than what’s arguably Baseball’s most popular ballpark. From the neighbors to the tourists, everyone wants in on the action—whether it’s in the grandstand, the rowdy bleachers, the surrounding streets or the festive rooftops beyond. So let’s play two and raise the “W” flag for the Friendly Confines of Wrigley Field.

There is probably no moment more Wrigley Field than what occurred during the sixth inning between the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies on May 17, 1979. Dave Kingman, a hit-or-miss masher who was mostly ‘hit’ in a brief but impressive spell for the Cubs, sent a monster fly ball soaring into the daytime jet stream of gusty winds blowing straight out. The ball not only sailed over the ivy-covered brick wall in left field, but also the packed bleachers full of delirious fans and even Waveland Street behind them, finally touching ground three houses down Kenmore Avenue, ricocheting off the front porch. A resident of the fourth house, apparently watching the game inside on WGN-TV, raced out of the house in an attempt to retrieve the ball before realizing he’d be beat to it by a posse of kids running down the street from Waveland. Kingman’s blast—his third of the day—trimmed the Phillies’ lead to 21-19; The Cubs would lose in 10 innings, 23-22.

There is probably no moment more Wrigley Field than what occurred during the sixth inning between the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies on May 17, 1979. Dave Kingman, a hit-or-miss masher who was mostly ‘hit’ in a brief but impressive spell for the Cubs, sent a monster fly ball soaring into the daytime jet stream of gusty winds blowing straight out. The ball not only sailed over the ivy-covered brick wall in left field, but also the packed bleachers full of delirious fans and even Waveland Street behind them, finally touching ground three houses down Kenmore Avenue, ricocheting off the front porch. A resident of the fourth house, apparently watching the game inside on WGN-TV, raced out of the house in an attempt to retrieve the ball before realizing he’d be beat to it by a posse of kids running down the street from Waveland. Kingman’s blast—his third of the day—trimmed the Phillies’ lead to 21-19; The Cubs would lose in 10 innings, 23-22.

It’s unknown whether Kingman’s tape-measure homer, estimated at 550 feet, was the longest ever smacked at Wrigley Field; it’s debatable as to whether it was even the longest hit by Kingman himself at the ballpark. The 1979 homer came a little over three years after another gust-aided moonshot, with Kingman playing for the visiting New York Mets, hit off the same house. In what almost became a case of a game literally coming into one’s living room, the ball just missed breaking through a window and into a room where resident Naomi Martinez was watching the game on WGN.

In a fabled ballpark jammed with history and legend, there’s much confusion about Wrigley Field. It wasn’t originally built for the Cubs—in fact, the baseball folks who bought the land didn’t even intend it to be used by its first true team, the Chicago Chi-Feds of the short-lived Federal League. It wasn’t the first ballpark with its name given to a corporate sponsor. It didn’t host its first night game in 1988, as many believe. Elwood Blues wasn’t the first person to claim a home address at the ballpark. And it wasn’t even the only Wrigley Field, as historians and witnesses of the Pacific Coast League’s glory days will tell you.

Kingman’s feats of strength are memorable, but their rankings on the list of great Wrigley Field moments are crowded out by other legendary events. The 1917 game, for instance, in which both pitchers (the Cubs’ Hippo Vaughn and Cincinnati’s Fred Toney) each threw no-hitters through nine innings. The opening game of the 1929 World Series, where the Philadelphia A’s Howard Ehmke—thought to be all but washed up in baseball—stunningly silenced the Cubs with a then-Fall Classic-record 13 strikeouts. Babe Ruth’s titanic “Called Shot” in the 1932 Series. Gabby Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’,” what some consider the best home run never seen, that helped decide the 1938 pennant race in favor of the Cubs. The 500th homer hit by Ernie Banks, fondly remembered as “Mr. Cub.” Seven hits from Pittsburgh’s Rennie Stennett in a 22-0 blasting of the Cubs in 1975, on a day when the wind apparently was only blowing out for the Pirates. The Sandberg Game. The Bartman Game. The Kerry Wood Game. And last and most heart-wrenchingly, the decision by Cubs ushers to deny a seat for a Billy goat its owner had paid a ticket for at the 1945 World Series—giving birth to a curse that would hex the Cubs for the next seven decades.

Beyond the spotlight and behind the scenes, the people who helped give Wrigley Field its character gave back the loyalty provided by a family which ran the Cubs for 62 years.

There was Pat Pieper, who did public address announcing at Wrigley—first with a bullhorn, then a microphone, from 1916 to his death in 1974 at age 88; when he wasn’t announcing, fans could catch him working at a nearby restaurant as the head waiter. Bobby Dorr, Wrigley’s groundskeeper from 1919-57, was so revered by Cubs owner William Wrigley that he was given a six-room cottage attached to the ballpark near the left-field entrance to live in, rent-free, for as long as he worked. Ray Kneip, the long-time head of concessions, had a devoted but odd routine of sifting through garbage cans at Wrigley to retrieve uneaten food and find out why it was thrown away. Bobby Lewis, the ballpark’s bouncer of sorts, filtered through the many fans who came to the gate hoping to get a free pass for the game’s day; outside of policemen, he rarely lifted the ropes for gratis access. Margaret Donahue, who began with the Cubs as a stenographer in 1919, worked all the way up to Vice President before retiring in 1958. And finally, from the stands, there was Jerry Pritikin, a Cubs fan since 1945 who emerged as the ‘Bleacher Preacher’ wearing a beanie with a propeller, claiming 2,000 converts to his ‘ministry’ where they abided by “The Ten Cub-mandments”—which included, “Thou shall not take the name of Ernie Banks in vain.”

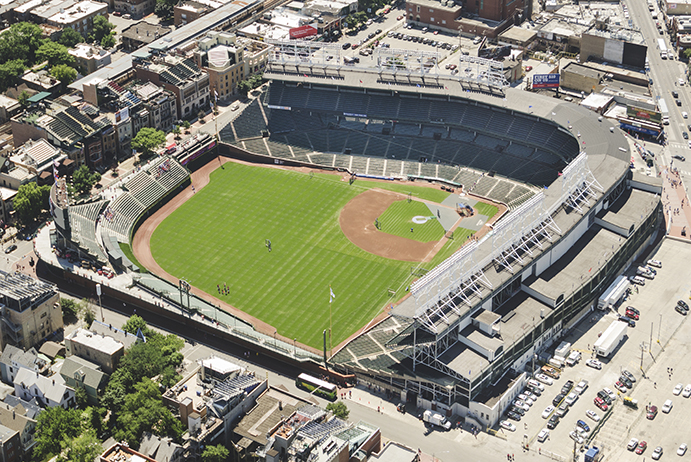

While other modern ballparks have situated themselves either downtown, within a revitalized ex-industrial district or as part of a business park, Wrigley Field remains the majors’ last neighborhood setting, co-existing through good times and bad for over 100 years in the Lakeview (or Wrigleyville) region four miles due north of downtown Chicago, and barely a mile west of Lake Michigan’s shore. The Cubs’ current regime has been allowed to reform the immediate area around Wrigley as a mixed-use mecca featuring hotels, businesses and retail, upgrading the ballpark itself to match the more diverse, vibrant nature of the neighborhood—a more affluent scene in 21st-Century times where young white-collar types, hippies, punks and the LGBTQ crowd share in the demographic footprint. Even some of the players live in the area; Ben Zobrist, who played for the Cubs from 2016-19, was known to bike to Wrigley in full uniform from a nearby residence.

Amid the local diversity and prosperity, Wrigley Field remains the heart and soul of the neighborhood. People come to soak up the ballpark experience and all its uniqueness within, from the ivy to the rooftops to the excellent grandstand sightlines—so long as you’re not sitting behind a post. It’s a bonus if the Cubs win.

Historian John Thorn wrote that Wrigley Field is “the architectural symbol of the city.” Sportswriter E.M. Swift more wistfully decreed that it’s “a Peter Pan of a ballpark. It has never grown up and it has never grown old.”

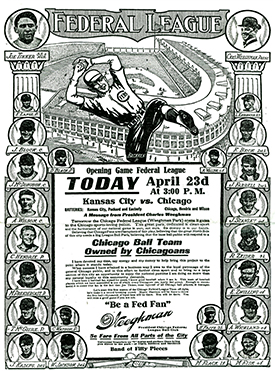

The very first game played at Weeghman Park, as Wrigley Field was originally called. The game between the Federal League’s Chicago Chi-Feds and Kansas City Packers drew 21,000—7,000 over capacity. (Library of Congress)

The Lunchroom King of Chicago.

Wrigleyville was originally the domain of the Chicago Lutheran Theological Seminary, which in the late 1800s built an expansive campus with mansion-like structures dotting the otherwise undeveloped landscape. And that was the way it wanted it to remain, but the creep of city growth became all too inevitable. In 1900, an elevated “L” train track was laid from the south that greatly accelerated urban growth, while industry established itself with a coal plant featuring five silos tucked into a triangular spot bordered by Waveland Avenue, Seminary Avenue and diagonal Clark Street—remaining there until 1961.

With cold feet, the seminary gradually decided to pack up, relocate and sell the land. Among those interested in buying was a trio of execs from the minor-league American Association, who in 1910 had aspirations of upgrading the circuit to major league status; for $175,000, they bought a plot of land across the street from the coal plant, on the east side of Seminary Avenue, with the intention of building a ballpark for a Chicago team to rival the Cubs and White Sox. But as soon as the ink dried on the purchase, other AA folks grew concerned about the outlaw status they were sure to be slapped upon from the established major leagues, and built up a majority opinion to remain a peaceful minor league option.

Stuck with the land, the three buyers watched the weeds grow until they learned of another third major league circuit, the Federal League, that was in the works—with its eyes on Chicago. The man they wanted to talk to was 39-year-old Charles Weeghman, who had become the Lunchroom King of Chicago with a chain of 30 eateries serving people who ate on-site in one-armed chairs—and was now interested in running a franchise for the startup league. Mutual interest led to a 99-year lease in which Weeghman would build a ballpark and pay rent to the AA trio.

Weeghman called on Zachary Taylor Davis, the noted Chicago architect who designed Comiskey Park for the White Sox three years earlier, to sketch out the look and feel of his new ballpark. Davis evoked New York’s Polo Grounds not so much for its bathtub shape but its sloping grandstand roof with a series of arched dormers. Yet when completed, the exterior beyond the roof lacked the palatial grace of Shibe Park, Forbes Field and Comiskey; its skeletal exposure of steel, ramps and common fencing, occasionally interrupted by smaller inner structures that looked as if shipping containers had been wedged into the steel frames, gave the overall façade an industrial, unfinished appearance.

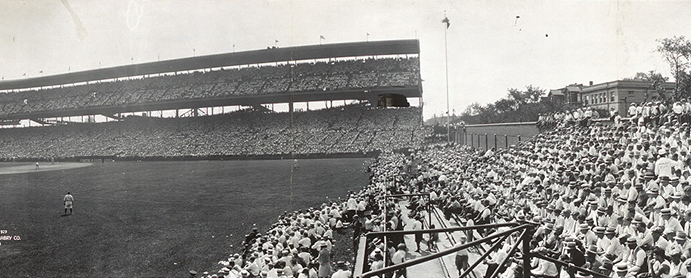

Built in an astonishingly quick six weeks for a mere $250,000, Weeghman Park—as Wrigley Field would originally be called—claimed 14,000 seats, almost all of them in a single-level grandstand that went pole to pole, with the back half of the tier covered by the roof. Pavilions were placed at each end of the grandstand, and a press box neatly positioned atop the roof behind home plate. A single bleacher structure, built with the idea of being permanent, protruded into right field from center to the gap.

A newspaper ad for the first game at Weeghman Park. Note the illustration of the ballpark displaying a more formal exterior than what actually ever existed.

In perhaps a volley of gamesmanship, the two established Chicago teams—the Cubs and White Sox—laughed off the Federal League, Weeghman’s Chi-Feds (later called the Whales), and Weeghman Park itself as a desperately placed spot in a relatively underpopulated part of Chicago. But if the Chi-Feds’ first game was any indication, Weeghman was ready to provide serious competition. An overflow crowd of 21,000 showed up despite chilly conditions made more miserable by cold winds blowing in from Lake Michigan. Led by former Cubs star shortstop Joe Tinker—he of the legendary Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance double play combo—the Chi-Feds eased to a 9-1 victory over the Kansas City Packers. Catcher Art Wilson drilled the ballpark’s first two home runs, and future Cubs pitcher Claude Hendrix went the distance. Kansas City starter Chief Johnson, who just five days earlier was pitching for the Cincinnati Reds but had jumped to the Federal League, was forced out after two innings—not because he gave up three runs, but because he was served on the mound with legal papers informing him to cease and desist playing in the new circuit. (Johnson was eventually allowed to stay with the Packers.)

Weeghman lent a good deal of hospitality to his patrons, something that would come to define Wrigley Field in the decades to come. He brought his lunchroom ethic to the ballpark, making Weeghman Park the first with permanent concession booths. In another first, Weeghman allowed fans to keep foul balls hit into the stands. On the field, Weeghman Park contained ridiculously small dimensions—particularly in right field, where it measured 298 down the line and 307 to the gap; room was a tad less cozy in left. Home runs were aplenty, at least by Deadball Era standards. While Sheffield Avenue restricted expansion of the field in right, all that got in the way in left was one of the seminary’s abandoned mansions. So in the middle of the 1914 season, the Chi-Feds sliced away its front porch, and for 1915 demolished the home entirely to provide even more outfield space—also deleting the right-field bleacher structure to yield more room there.

The Chi-Feds became a Federal League power—winning the pennant by a single percentage point in their second season—but that was more a reflection of the poor state of the FL in general. Badly in the red after two seasons, the fledgling circuit threw in the towel, but not without a legal fight. As part of a settlement between the FL and the National/American Leagues, Weeghman was allowed to buy the Chicago Cubs and move them to Weeghman Park from West Side Grounds, their rotting wooden home since 1893. But the purchase fee was set at $500,000; Weeghman didn’t have that, so he set about finding nine other investors who, along with himself, would pitch in $50,000 each to complete the acquisition.

One of those investors was William Wrigley, a flamboyant, industrious man who made his fortune on chewing gum. In his first couple years as one-tenth of the Cubs’ ownership group, Wrigley sat in the background, but when the Cubs won the NL pennant in 1918 and were compelled to stiff-arm Weeghman Park (since expanded to 18,000 seats) for the South Side and larger-capacity Comiskey Park, he likely knew that Weeghman—whose lunchroom empire had all but collapsed due to World War I, the Spanish Flu pandemic and soaring food prices—was financially hurting. Weeghman needed an off-ramp, and Wrigley obliged by buying him out; a few years later, Wrigley would consolidate additional team stock and become the Cubs’ majority investor.

A split-screen view of Wrigley Field in 1929 after a pair of major renovations over the previous decade—including the addition of the upper deck in 1927. (Library of Congress)

High Times.

Hardly standing pat on what he’d acquired, Wrigley initiated a series of expansions to Cubs Park, as Wrigley Field was briefly known after his purchase of the club. For 1923, he split the grandstand into three sections, rolling two of them (behind home plate and the third-base side) 60 feet back from the field, and filling in the gaps with new seating; not only did this lead to more seats but also a bigger field (adding new bleachers), shedding the ballpark’s early reputation as a claustrophobic bandbox. A few years later, a second expansion featured the addition of a second level to the grandstand and the lowering of the playing field three feet. These enlargements, costing a then eye-opening sum of over $2 million—or 10 times the original budget to build Weeghman Park from scratch—doubled capacity to over 38,000.

Wrigley ensured that any ballpark he put his name on—as he finally did in 1927 after the various upgrades—would not be taken for granted by its patrons. Wrigley Field was clean and always freshly painted; rubber mats were even placed on the aisles between the concourses and seats to reduce the spread of mud and dirt. “You can’t sell goods in a grimy package,” Wrigley often insisted.

To get more fans to show up to his beautiful ballyard, Wrigley promoted the Cubs by broadcasting home games on radio. And not just one local radio station, but at times as many as seven. Other major league owners would have thought that Wrigley was out of his mind; after all, why go to the ballpark when you can listen at home for free? But Wrigley knew better; the omnipresent exposure led to an enlarged audience that had the Cubs top-of-mind; at some point, many of those listeners would want to bolt over to Wrigley Field. And that they would.

It didn’t hurt that the Cubs had become an excellent team as the 1920s roared on. Wrigley, with a right-hand man in William Veeck Sr.—whose bulldog face meant business, and had only been hired by Wrigley so he could stop criticizing the team while penning opinions for the Chicago American—oversaw a flamboyant roster led by the legendary Hack Wilson, who in 1930 used his 5’6” frame and muscular 190 pounds to mash 56 home runs with an all-time record 191 runs batted in.

With a beautiful ballpark, a constant contender and dominance over the regional airwaves, the Cubs packed them in at Wrigley Field as no team in major league history had previously done. The 1927 Cubs became the first in NL history to draw over a million fans; they re-topped the milestone in each of the next four years, peaking in 1929 with 1,485,166 paid customers—a major league record that would hold until 1946, and the most Wrigley would attract for another 40 years.

The Cubs’ Hack Wilson crosses the plate at Wrigley Field after one of his 56 home runs in 1930. While that figure remained a National League record until 1998 thanks to future Cub Sammy Sosa (along with Mark McGwire), Wilson’s 191 RBIs from the same year remain an all-time record. (Library of Congress/Chicago Historical Society)

Female spectators made up a sizeable percentage of the Wrigley Field gate, in large part due to the Cubs’ enormously successful staging of Ladies’ Day. On June 27, 1930, the promotion proved to be too successful; of the 51,556 who jammed into Wrigley Field—its largest gathering ever—over 30,000 of them were women admitted in without charge. Another 50,000 were reportedly turned away and, naturally, chaos ensued—with paid ticket buyers trying to reclaim seats taken over by the ladies, along with a number of girl-on-girl brawls. William Wrigley realized he had created a monster, so for future Ladies’ Day games he would request that women call the ticket office and reserve a free spot at the ballpark.

Ladies’ Days was just one of many women-centric moments of interest dotting the Wrigley Field timeline. One woman who did pay for her tickets did so for every 1929 game—thus becoming the Cubs’ first unofficial season ticket holder. In 1943, the Wrigley regime was the primary force behind the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, a wartime alternative to the men’s circuits whose talent was depleted by military-bound players, and later popularized by the 1992 film A League of Their Own. In its first season, the AAGPBL hosted an exhibition at Wrigley Field between league All-Stars and a team from the Women’s Army Corps, played at night before 7,000 fans; the contest is known as the first played under (portable) lights at Wrigley Field, predating the Cubs’ first night game by 45 years. And there’s the aforementioned VP Margaret Donahue, the first high-end female major league exec who toiled her way near the top, rather than have ownership inherited into her lap (as it happened for the Cardinals’ Helene Hathaway Britton).

Every year from 1926-39, the Cubs finished with a winning record and took four NL pennants, at a cyclical three-year rate (1929, 1932, 1935 and 1938). But they came up short each time at the World Series, with the most stinging of those defeats taking place in 1932 during a testy showdown against the almighty New York Yankees and Babe Ruth, who sparked legend—perhaps without realizing it—with his “Called Shot” home run.

Debate rages to this day as to whether Ruth was pointing two fingers toward Wrigley’s center-field bleachers to let Cubs pitcher Charlie Root know where he’d hit the next pitch, or if he was just letting the heckling Cubs know that there were two, not three, strikes on him. Not debated is what Ruth did next—launching a titanic shot well into those center-field bleachers. The usually boastful Ruth seemed caught off guard when asked about the moment after the game, and he later privately confided to others that he didn’t really call the shot, but others remain otherwise wholly convinced. Future U.S. Supreme Court justice John Paul Stevens, who attended that game and lived long enough to see the Cubs finally win it all in 2016, swore that Ruth called it. “That’s the ruling I will not be reversed on,” he insisted.

Wrigley Field’s center-field scoreboard remains virtually the same one first used in 1937. Located 490 feet from home plate, no player has ever hit it. (Flickr—Rob Pongsajapan)

The Next Generation.

In January 1932, William Wrigley died; a year and a half later, William Veeck passed as well. Many worried that the loss of the two people most responsible for Wrigley Field’s runaway success—losing them in the midst of the Great Depression, no less—would bring an end to good times. But the sons of the fathers came through not just in maintaining, but transcending, the Wrigley Field experience.

Inheriting the Cubs was Wrigley’s only son Philip, who may have lacked his father’s bravado and baseball acumen, yet fully grasped the value of a clean, beautiful ballpark and its relationship with the surrounding community. He never borrowed from the till of his chewing gum empire; whatever money he made from the Cubs he put back into the team and Wrigley Field itself, constantly having the venue repainted, maintained and upgraded. For Philip, comfort outweighed profit; he installed wider seats at the cost of a smaller capacity, and made the press feel at home with both a spacious room featuring lockers and a postgame bar called the Pink Poodle where reporters would sometimes be joined by Cubs coaches and scouts. Outside at the main entrance, Wrigley in 1934 installed the famed marquee, graced by mild art deco motifs and originally clad in blue before turning red and, briefly, green and even purple (for a Northwestern football game in 2010).

For a brief but very pivotal time in the late 1930s, Wrigley was joined in the front office by Bill Veeck, the son of William Sr. Though barely in his 20s, Veeck was already beginning to display some of the showmanship prowess he would master in later years as owner of the Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns and Chicago White Sox. When Wrigley rebuilt the bleachers into a boomerang-shaped concrete structure protruding into the outfield—resulting in Wrigley Field’s current-day dimensions with cozy (368 feet) gaps but relatively roomy (355 left, 353 right) corners—it was Veeck’s job to embellish them.

The ballpark’s original scoreboard, impressive as it was when Wrigley Field opened, would be no match for what Veeck had in mind for a replacement. Planted at the back of the center-field bleachers, the new board was so detailed and intricate that the contractor hired by the Cubs to build it bailed, convinced he could never deliver on something so ambitious. It left Veeck and a bunch of Cubs employees to take all the components and somehow piece it together themselves. What a job they must have done; it’s essentially the same scoreboard used today.

Gracing the scoreboard was a series of eight Chinese elm trees, four on each side, spaced out in planter boxes at the back of the pyramid-shaped bleachers in center. It was a beautiful sight, until the fierce lakeshore winds ripped the leaves away. Time and time again, the trees were replanted—and time and time again, the gusts stripped them bare. After about 10 years of this frustrating routine, the Cubs gave up and trashed the trees.

Only at Wrigley Field: Outfielders fail to locate a ball hit into the ivy and throw their arms up, asking for a ground-rule double per Wrigley rules. (Flickr—Dave Herholz)

Absolutely Di-Vine.

Another new botanical display at Wrigley Field would outlast the trees and become the ballpark’s signature element. Veeck, whose written recollections have been advised by many to be accommodated with a grain of salt, claimed he visualized the idea of putting ivy on the brick outfield walls after seeing it done at a minor league ballpark in Indianapolis. The descendants of groundskeeper Bob Dorr certainly believe Veeck took too much credit for the Wrigley ivy—but whoever was responsible, the planting of the vines provided the ballpark with its perfect touch. Not that many of the outfielders who’ve had to deal with it would agree.

Players can lose a ball in the ivy, just like a neighborhood kid on the sandlot might when a ball barges its way into the bushes; they can immediately raise their arms and surrender to a ground-rule double, but if they don’t, the ball is still considered in play and the runner can fly around the bases forever. Cubs rookie outfielder Julio Zuleta didn’t heed the ground rules in 2000 when the Phillies’ Kevin Jordan smacked a ball into the left-field ivy; Zuleta searched and searched as Cubs teammates desperately yelled out to him to raise his arms, but he fruitlessly continued as Jordan completed an inside-the-park home run.

The great Roberto Clemente once dared to search the ivy and did come up with the ball. Or so he thought. When he threw it back toward the infield, he was startled to see it die to the ground some 10 feet in front of him. Turned out, it was a bright white soda cup.

Though elegant and cushy in appearance, the ivy provides little protection for the brick wall behind—and outfielders, by and large, know that. The Cubs added two feet of warning track in front of the ivy in 2008 after outfielder Alfonso Soriano had grown especially hesitant to charge full speed toward the wall. But sometimes it was even the ivy that spooked players; legend has it that Lou Novikoff, who played for the Cubs in the early 1940s, shied away from making contact with the ivy. When asked why, he thought it was poison ivy.

Worse than the ivy-covered brick are six metal maintenance doors embedded within the outfield wall, all of them in play and not hidden by the ivy. In 2014, the Cubs’ Junior Lake was daredevil enough to race at full speed toward the wall, but also unfortunate to make his sliding catch attempt against one of the six doors—banging his head hard into it. Needless to say, his day was done, but he escaped serious injury. (Memo to the Cubs: There is such a thing as “padding.”)

The Gust Belt.

Another longstanding Wrigley Field tradition born out of the Wrigley/Veeck II window was the “W” flag. To stay connected with the neighborhood, Philip Wrigley wanted to let residents returning home from work know how the Cubs did during the day. So starting in 1938, on a flag pole above the new scoreboard, a white flag with a blue “W” was raised if the Cubs won—or a blue flag with a white “L” if they lost. When it got too dark to see the flags, Wrigley rigged up a series of electric lights to spell out “W” or “L” depending on the result. If that wasn’t enough, Wrigley at one point placed a mini-scoreboard outside Wrigley Field’s front entrance to let people know what was going on inside during the game, lest anyone still wanted to grab a ticket and check out a close game in the late innings of play.

Now as then, the “W” and “L” flags are hardly the only ones flying at Wrigley Field. In fact, they seem to be everywhere; one Sporting News writer once counted 107 during a 1937 game. There’s decorative and tribute flags spaced out atop the upper deck. There’s flags honoring Cubs Hall of Famers and Jackie Robinson tied to the foul poles. There’s flags for every NL team, draped out in order of standings on three different ropes tied between the scoreboard and a T-shaped flag pole above it, like a maritime display you’d see on a yacht.

When you’re at Wrigley Field, you’re going to get a good look at what these flags look like, because chances are they’re going to be fluttering hard in the air as Chicago’s famous gusty winds give fans a good idea of what kind of game you might get. If the gusts are coming in off the lake, straight toward home plate, expect deep flies to die behind the infield and low-scoring games to rule. But when they come in from the south, toward the outfield, look out.

Every few years or so, Wrigley Field gets subjected to “one of those days,” when howling winds blowing straight out toward the bleachers make no lead safe as the runs rack up; by comparison, Denver’s mile-high Coors Field doesn’t feel so bad to pitchers. Twenty times and counting, a team has scored 20 or more runs in a game at Wrigley; there have been two games where both teams notched 20-plus. One is the aforementioned Dave Kingman-a-thon from 1979; the other was a 1922 game, also against the Phillies, in which the Cubs shot out to a 25-6 lead after four innings before holding on for dear life as the Phillies drew it to 26-23 in the ninth—loading the bases to bring the go-ahead run to bat—before running out of outs. The 49 combined runs remain a major league record.

Game Four of the 1945 World Series between the Cubs and Detroit Tigers at Wrigley Field. The Cubs lost the series, which was notorious for the moment when a Chicago tavern owner had his Billy goat denied permission into the ballpark—giving birth to a curse that would last over 70 years. (The Rucker Archive)

Hold the Bulbs.

After the 1941 season, Philip Wrigley was ready to go all in on lights at Wrigley Field. Nine of the other 13 major league ballparks had wired up for night ball, and it was just a matter of time before the other four jumped on board. By December 6, virtually all all of the needed materials for lights were at Wrigley Field, ready to be erected—but a day later, Pearl Harbor was attacked and America was drawn into World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt encouraged baseball to play on with as many night games as possible to provide escapist entertainment for plant workers and others trying to get their minds off of the war, but Wrigley had a better thought; he donated all the lighting materials—including 165 tons of steel and 35,000 feet of copper wire—to the U.S. military to help with the war effort. The government said thank you very much, and Wrigley Field trudged on through the war years—and well beyond—playing exclusively under natural light.

Following the end of the war in 1945, the other ballparks lit up, with Detroit’s Briggs (Tiger) Stadium being the last among them in 1948. Wrigley, who had come within weeks of hoisting up the lights, was in no hurry to join the rest of the crowd. Increasingly, he felt an obligation to the surrounding community to stay day-centric at Wrigley Field, unwilling to disrupt the evening lives of his neighbors.

For the most part, batters loved day baseball at Wrigley Field because the bright conditions and warm weather made the ball easier to hit. Visiting players, in particular, could only imagine how much fatter their career stats would have been playing half of their games at Wrigley. “Boy, how I’d like to have just one season playing in this ballpark,” beamed Babe Ruth after hitting his “Called Shot” homer in 1932, “I’d hit a million.” Phillies third baseman Mike Schmidt, in 138 career games at Wrigley, racked up 50 homers—including four during a wind-blown 1976 slugfest won in 10 innings over the Cubs, 18-17. Fellow Hall of Famers Willie Mays and Hank Aaron share the top of the ballpark’s all-time home run list among visitors with 54, though they each needed 41 more games than Schmidt to do it. And then there’s Dave Kingman, who belted 69 over the fence (and yes, sometimes beyond Waveland Avenue) in 241 games combined between his time as a Cub and countless other visiting ballclubs; more impressively, Kingman batted .297 at Wrigley—but just .227 everywhere else.

One thing that players universally loathed, however, was the Cubs’ strange and consistent issues with rigging up an acceptable batter’s eye in center field. St. Louis Cardinals icon Stan Musial once called the background “murder,” adding, “and that’s exactly what it will result in one of these days if something isn’t done.” The simple solution, many believed, would be to close down a section of center-field bleacher seats and put up a dark wall—after all, losing seats was not anathema to Philip Wrigley, who was placing wider seats in the grandstand at the cost of lower capacity—but it seemed puzzling that the Cubs couldn’t (or wouldn’t) commit to the obvious choice. The oddest ‘solution’ came in 1963 when the team rigged up an eight-foot wire extension above the center-field wall, stretching 64 foot wide. All that the “Whitlow Fence”—named after Cubs athletic director Robert Whitlow, who came up with the idea—seemed to do was take home runs away from batters, enraging them even further. It barely lasted more than a year.

Detail from Wrigley Field’s exterior includes decorative green iron fencing and terra cotta tiles providing slim cover for arriving fans. (iStock)

The Lonely Confines of Wrigley Field.

The postwar era was not kind to the Cubs. Starting in 1947, the team endured two decades with only one winning season (and barely, at 82-80 in 1963). Every step forward seemed to lead to two steps back, most memorably reflected in the ill-advised “college of coaches” scheme in which, from 1961-65, the Cubs trashed away the manager concept and enlisted a group of eight coaches to lead the team. During the second year of this folly, in 1962, they lost over 100 games for the first time ever.

The Cubs’ fall from grace was exacerbated with a rise in local and regional competition. The White Sox, slowly struggling to recover from the Black Sox Scandal, finally were restored to competitive life in the 1950s and regularly began to outdraw the Cubs, winning the AL pennant in 1959 under the marketing brilliance of old friend Bill Veeck. Ninety miles to the north, the Boston Braves relocated to Milwaukee and took baseball by storm, drawing up to two million fans a year—including some of the Cubs’ more distant fans.

Attendance at Wrigley Field suffered from this perfect storm. The Cubs annually drew over a million fans in the immediate years after the war, but ticket sales faded as the losing persisted into the 1950s. Worse, the team’s marketing philosophy to sell more seats was, basically, no philosophy at all. “We have no plan,” team VP John Holland admitted to The Sporting News in 1962. “No sales pattern. People buy what they want, when they want it. That’s long been the Cub practice.” This neglectful strategy resulted in barely 600,000 fans attending Wrigley Field in 1962; for one late game in 1966—in the midst of another 100-loss season—the team drew an all-time ballpark-low gathering of 440.

As awful as this period was in the standings, it’s populated with memorable and popular names in Wrigley Field history. Topping the list is Ernie Banks, the team’s first African-American ballplayer who was a bundle of baseball sunshine, immortalizing the term “Let’s play two” and referring to the Wrigley Field experience as “the epitome of American life.” He would go on to play more games (1,285), collect more hits (1,372) and drive in more runs (909) than any other Cubs player at Wrigley; his 290 home runs fall just three short of Sammy Sosa, who likely had help from the medicine cabinet. Banks managed back-to-back MVPs in 1958-59 for Cubs teams with losing records, making the best of a Hall-of-Fame career in which he’d play the most major league games (2,528) without a single postseason appearance.

The other key icon of this time was to be found in the broadcast booth. Jack Brickhouse began working with the Cubs in 1940 doing play-by-play at age 24, but his claim to fame wouldn’t come until 1948 when he became the team’s TV voice, as the Cubs became just as aggressive at showing every game on the emerging tube as they had two decades earlier with radio. Brickhouse would remain a staple on WGN-TV all the way to his last call in 1981, beloved by many Chicago fans who came to embrace his home run calls of “Hey! Hey!”

While the Cubs continued to lose during this time, Wrigley Field continued to be a winner with those who showed up. The ballpark was continuously painted and repainted, strengthened and restrengthened, and updated. The most Jetsons-like move was to install low-incline escalators on some of the spectator ramps—but they caused havoc on the first day of their use when three male fans had their pants legs caught up in the conveyor belt.

Philip Wrigley managed to net the money needed to make these improvements not solely because of the Cubs, but also from other events at Wrigley Field. Besides baseball, the ballpark hosted wrestling and boxing bouts, the Harlem Globetrotters, and once even a wintertime ski jumping exhibition in which a ramp was constructed from the top deck, with participants gliding down onto the field. But among other sports, Wrigley profited mostly off of football; the NFL’s Chicago Bears were a tenant from 1921-70, drawing upwards of 50,000 fans thanks to portable bleachers planted atop an otherwise vacant right field. That was the easy part; the hard part was trying to wedge a regulation football field into Wrigley’s cozy field dimensions, with its small gaps and miniscule foul territory. It was done, but not without peril to the players; parts of the north end zone (left field) literally butted up to the ivied brick wall, while at the other end, a small corner area of the south end zone literally included a drop-off into the first-base dugout. When college football came to Wrigley for a one-time event in 2010 featuring Northwestern and Illinois, they basically played a half-court version of football—with the offensive team always facing toward the more spaciously surrounded end zone to minimize potential collision with the ballpark bricks.

Amid all the ongoing improvements at Wrigley Field, Philip Wrigley continued to say no to lights, citing his good-neighbor policy with the community. His position had only hardened since his 1941 donation of lighting materials to the military; in fact, he believed that the Cubs’ continued play under the sun was “pioneering daylight ball” and that other teams would soon begin abandoning lights. Wrigley criticized newer stadiums such as the Houston Astrodome, calling them “bazaars” with “restaurants and shops all over the place,” and also said no to powerful Chicago mayor Richard Daley’s idea of building a cutting-edge, 70,000-seat multi-purpose stadium for all Chicago pro sports teams, saying he didn’t think public money should be used to construct it. “Maybe I’m old-fashioned,” he told The Sporting News, “but I still like a baseball park to be built for baseball.”

On occasion, Wrigley did bend, a little—saying he might install lights, but only to play out afternoon games that otherwise would get called on account of darkness. But he never did, and he stubbornly resisted pressure from other NL owners who fumed and argued that night games would bring more revenue, and from a Cubs stockholder who sued Wrigley in 1966, linking the team’s deep amount of red ink to a lack of night ball. The stockholder lost, as the Cubs’ defense attorney cited “vicious” evening competition from TV, theaters, shopping centers and “visiting with friends,” while stating that Wrigleyville was an eerie place after dark. “Danger lurks at night,” he orated.

Wanting to be Somebody, and a Bum.

Honest to a fault, Philip Wrigley always insisted that the only way he could put more money into the Cubs and extend upkeep for Wrigley Field was for the team to start winning, thus bringing in more fans. That finally started to happen in the late 1960s when he hired a true, proven manager (Leo Durocher), and accommodated Ernie Banks with three young future Hall of Famers in quiet slugger Billy Williams, spirited third baseman Ron Santo and perennial 20-game ace Ferguson Jenkins. The Cubs embarked on a long-overdue run of success, highlighted by a pennant run in 1969 that melted down the stretch as the “miracle” New York Mets roared past them.

While the postseason continued to elude the Cubs, they at least began to draw again, occasionally pulling in over 1.5 million fans through the 1970s. The friendly confines not only got more populous, it became rowdier as well. This was especially apparent in the bleachers, where younger fans jammed in behind the ivy and began drinking, rooting and needling opposing outfielders—sometimes in the coarsest of terms. The trendsetters for this movement were the Bleacher Bums, a group of some 10 hard hat-wearing dudes who made the noise of 1,000 and gave life to Wrigley’s back end. The Bums attracted enough followers and fame that they became the basis for a successful 1978 play, overseen by future star actor and loyal Cubs fan Joe Mantegna.

By 1970, the bleacher rowdyism became so much of a problem that the Cubs had no choice but to temper it. To prevent fans jumping onto the outfield or stealing balls from outfielders, the team installed an angled “basket” netting at the top of the wall, restricted alcohol sales to concessions stands (instead of from roving vendors), ceased selling standing room tickets and installed video surveillance cameras.

A mild birds-eye view of the back of the center-field bleachers, beautified by the flag graphic at the back of the scoreboard. (iStock)

“Let Me Hear Ya’!”

Philip Wrigley died shortly after Opening Day 1977; two months later, his wife passed as well. The advent of free agency probably would have driven Wrigley out of the game anyway, but his son Bill, inheriting the Cubs, gave it a shot nonetheless. Saddled with a $40 million estate tax, the younger Wrigley found it challenging to push forward with ownership at a time when major league payrolls were beginning to spiral upwards. By 1981, he caved; for $20.5 million, he sold the Cubs to the Chicago Tribune Company, which besides the newspaper also owned WGN, TV home of the Cubs and growing nationwide force on the fledgling basic cable landscape.

Tribune had more in mind for Wrigley Field than a simple recoating of paint. They expanded the office space within the ballpark and aggressively marketed the team to the masses, something Wrigley never bothered with. For the moment, Tribune stayed the course on the lights issue, declaring that night games were not in the Cubs’ future.

The new owners did score a major coup by replacing the retired Jack Brickhouse with Harry Caray, the colorful, jovial broadcaster who’d been working the mike since 1945 for numerous teams, most principally the Cardinals. The Cubs poached Caray away from the White Sox, where he worked the previous decade, and at Wrigley Field he brought over some of his more endearing routines such as the occasional broadcast from the bleachers among the Bums, and his sing-a-long of Take Me Out to the Ballgame with the fans during the seventh inning stretch, a ritual he began back in 1976 with the White Sox. Sure, Caray could slaughter players’ names like Jose Vizcaino or Heathcliff Slocumb, but the fans loved him—and he loved them back, often hanging out at nearby bars after the game and chugging one Budweiser after another until closing time.

The 1984 season is the year the Wrigley Field experience permanently shifted into high gear. Lifted by a breakout effort from MVP second baseman Ryne Sandberg and Cy Young winner Rick Sutcliffe (16-1 in 20 starts following a June trade), the Cubs beelined to the NL East title; the fans, intoxicated by Caray’s exuberant calls on WGN, came running not just to Wrigley, which drew over two million for the first time ever, but also the rooftops on the surrounding buildings. Marking their first postseason appearance in 39 years, the Cubs won the first two games of the National League Championship Series against the San Diego Padres and looked ready to, finally, return to the World Series—but they collapsed at the worst moment, losing the next three (all in San Diego) to bow out.

Though the 1984 Cubs provided fans with their only winning record between 1972-89, the uplifted environment at Wrigley Field and the immense exposure the team was receiving on nationwide cable reset the attendance bar for the long term, as an annual gate of two million became the norm and only grew from there.

And then there were lights: After being caught in a tug-of-war between local politicians who Wrigley Field forbid night games and MLB execs who threatened to move Cubs playoff home games to St. Louis, the Cubs were finally given the okay to install lights in 1988. (Flickr-CJD)

Night Moves.

The Cubs’ return to the playoffs exposed the challenges of a daytime franchise coexisting with a league dependent on night ball. The World Series had firmly become a nocturnal event, maximizing national television viewership and, thus, revenue from advertisers. During their 1984 postseason run, the Cubs were already told that they would have to forfeit home field advantage if they made the World Series, as any day game would gross Major League Baseball $6 million less in broadcast ad dollars than one played at night. It got worse a year later; the Cubs were informed that if they ever reached the World Series without lights at Wrigley, they would have to move their home games to another venue—likely St. Louis’ Busch Memorial Stadium, home of the rival Cardinals.

With pressure ratcheting up on the Cubs, Tribune changed its tune on lights and called for Wrigley to be lit up. Opposition would be fierce; a grass-roots neighborhood group called CUBS (Citizens United for Baseball in the Sunshine) evolved as formidable legal foe and successfully lobbied both the city and state to come up with ordinances that effectively blocked night baseball at Wrigley. One banned athletic events played past midnight in a facility that hadn’t previously installed lights (like Wrigley) within a city of a million or more people (like Chicago). The other banned sports in a stadium not enclosed (like Comiskey Park) and seating 15,000 or more spectators (like college stadiums). Both measures might have well as just said, “Lights banned at Wrigley Field.”

Stuck between MLB and the politicians—or, in other words, a rock and a hard place—the Cubs had no choice but to fight back. They sued both the state and the city, lost, appealed to the state Supreme Court, and lost again. Dallas Green, the fiery former Phillies manager now serving as Cubs president, put his physically intimidating, combative disposition on display by publicly insisting that if no lights were installed at Wrigley, there would be no Wrigley. To back his threat, officials in the northwest suburbs of Rosemont and Schaumburg began laying out plans for a possible new Cubs ballpark.

Gradually, the politicians realized that MLB was not going to blink on moving a future Cubs postseason series to St. Louis, which would have proven embarrassing to Chicago. They changed course and allowed Wrigley Field to have its lights—provided that the number of night games per season be limited to 18, with none on Fridays, and that the Cubs would ensure a long-term presence at the ballpark.

Costing $5 million, the lights that finally went up at Wrigley would have an appropriately classy and unobtrusive look, a delicate-looking display of steel and retro arc patterns. They were first switched on for an August 8, 1988 game against the Phillies, with a festive, sold-out atmosphere and perhaps one dissenter: The Good Lord, who after providing all that natural light for 74 years literally rained on the proceedings, washing out the game before the fourth inning was complete. The Cubs tried it again the next night, and got all nine innings in as they defeated the Mets in the first ‘official’ game under the lights, 6-4, before another packed house.

After the popularity of the Cubs exploded in the 1980s, ballpark-style seating popped up on one rooftop after another with a view of Wrigley Field. At first the Cubs fought the rooftop owners—then bought them out, kept the seats, added bars underneath and reaped the profits. (iStock)

The Second Bleachers.

With one battle behind them, the Cubs geared up for the next one. For years, the rooftops on the buildings behind the outfield bleachers provided clear, often free views of the playing field at a slightly farther distance. At first, the only people taking advantage were residents and perhaps a few friends who climbed up the ladders with their lawn chairs, hibachis, beer coolers and suntan lotion. In 1980, Murphy’s Bleachers—one of many longstanding watering holes around Wrigley Field, situated behind the center-field entrance at the corner of Sheffield and Waveland—built the first formal rooftop bleacher section three doors down. But a few years later, a group called the Lakewood Baseball Club propped up another rooftop stand further down Sheffield, near the right-field foul pole—and began charging fans to sit there. This was one step too far for the Cubs and team president Donald Grenesko, who like Demi Moore in A Few Good Men “strenuously” objected to the outside paid admissions. “If they can do it,” Grenesko fumed, “then the people next door can do it.”

Grenesko was right. The people next door did do it. And the people next to them. And so on and so on, until nearly every rooftop with a view looking inside Wrigley Field had bleachers rigged up. These weren’t just rustic benches you’d find at a little league park, but ballpark-type seats with suite-style catering. It was a cottage industry unlike anything previously seen in baseball, becoming almost as hot an item as the best seats inside Wrigley Field. Even the players couldn’t resist; during one 1993 game, Cincinnati pitcher Tom Browning took advantage of his day off to sneak out of the ballpark, walk across the street and hike to one of the rooftops to party with the other fans, waiving across the way to his teammates.

In 2002, the Cubs went to war with the rooftops. They put up a green wind screen behind the bleachers to block the views of rooftop patrons, and sued the owners for copyright infringement—claiming that the Cubs and Wrigley Field brands were illegally being used to sell and mimic an in-game experience. A truce was declared two years later, with the rooftop owners agreeing to give the Cubs 17% of their receipts.

The peace would be short-lived, as rooftop folks found a new foe a decade later in Tom Ricketts, a life-long Cubs fan who met his wife in the Wrigley bleachers and, in 2009, bought the team from Tribune for $845 million. As part of Ricketts’ massive renovation of Wrigley Field—called the 1060 Project—video boards were propped up behind both the left- and right-field bleachers, further disrupting the view of rooftop patrons. In what seemed a rich irony, the rooftop owners sued the Cubs, claiming the team was violating terms of the 2004 agreement. Their case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear the arguments because the 1060 Project was “approved by governmental authorities.”

Ricketts ultimately decided, why fight when you can buy? He was able to persuade his way to buying 11 of the rooftop properties, which now goes under the name of Wrigley Rooftops LLC. The visual obstacles remain, and the prices are not cheap, but Ricketts’ rooftop properties include ballpark-style food and drinks (alcoholic and non-alcoholic) in a bar-like area one floor below with flat screen TVs showing the game you might half-miss upstairs.

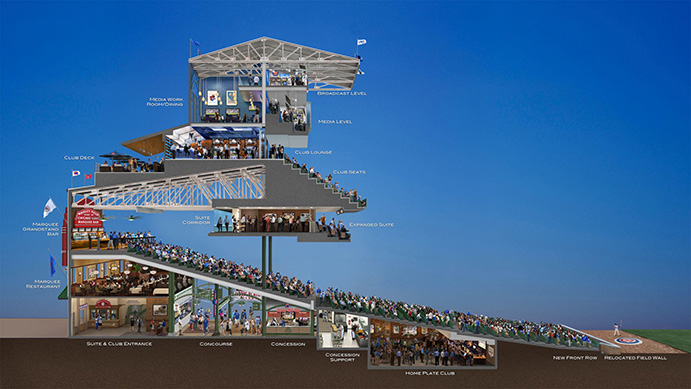

This cross-section rendition of Wrigley Field upgrades during the 2010s include underground clubs and a concessions area on the upper deck with views of Chicago. (Chicago Cubs)

From Dump to Deluxe.

The 1060 Project provided a breath of fresh air for those who thought Wrigley Field had decayed to a point where it could no longer be defended as being fashionably antique. “They have to make that park livable,” sportswriter Peter Gammons once wrote. “It’s a dump.” Veteran slugger Lance Berkman concurred, with added edge: “If they’re looking for a guy to push the button when they blow the place up, I’ll do it.”

Ricketts couldn’t do whatever he wanted to upgrade Wrigley Field; because the ballpark was protected as a national landmark, he needed an okay from government. That meant going through Chicago mayor and political rival Rahm Emanuel, who for a time wouldn’t even answer Ricketts’ phone calls after his family bankrolled an ad campaign tying then-President Barack Obama, Emanuel’s good friend, to a former pastor engaged in antisemitism. Once the toxic air cleared, Emanuel and the City Council blessed the $500 million renovation—which swelled to $750 million by the time of its completion, fully paid for by the Cubs.

The modernization of Wrigley Field would be all encompassing—and not without some unexpected obstacles. In digging through the ballpark’s bowels, it was discovered that the steel columns holding up Wrigley were so degraded at the base that they needed to be entirely replaced—with new supports driven deeper into the bedrock. And it was discovered that the ivy had become stronger than the brick wall it covered, with vines growing into the bricks, weakening them to the point that contractors reconstructing the outfield wall could simply remove some bricks not with a chisel but, instead, with their own hands.

More cosmetically, seats were replaced, the bleachers upgraded with lounge-like standing areas, and the slightly angled exterior roof was partly shaved away to make room for hybrid concourse/patio areas, keeping upper deck fans from having to go down to the field-level concourse to fetch food or a bathroom. More earth was excavated away under the ballpark bowl to stash in a series of new clubs and lounges—alas, none of them fully accessible to all ticket buyers.

For the players, what was considered the majors’ worst clubhouse was transformed into one of the best. Located outside of the ballpark, underground below the grassy portion of the adjacent triangular plot now referred to as Gallagher Way, the clubhouse is the heart of a 30,000-square foot complex that also includes spacious training and weight areas, as well as a players’ lounge. A swanky vibe permeates the facility, from the mod lighting and stylings in the circular locker room—which, by the way, measures 60’6” in diameter—to a take-off of the famed “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign in the lounge.

Outside of the two new big video boards behind the bleachers, the renovated Wrigley Field, on the inside, really doesn’t feel any different than it might have back in 1937. And that’s the way the Cubs intended it. “This had to be the ballpark your grandfather recognized,” said Ricketts.

The biggest sea change to Wrigley took place outside of the ballpark, particularly behind the third-base side of the structure. The triangular plot of land which once housed a coal plant and later a parking lot was transformed into Gallagher Way—a park-like area that includes grassy picnic space and a splash pad for kids to run through on a warm day. It’s cradled on the north end by a six-story building containing a restaurant, Starbucks, Cubs souvenir store and the team’s front offices. The park area was thoughtfully designed to connect with the neighborhood, as it’s used for farmer’s markets, concerts, ice skating and other community activities throughout the year.

The Cubs’ brand is, of course, well represented in Gallagher Way—most ceremoniously with the bulk of Wrigley Field’s statues honoring Cubs greats of the past, from Ernie Banks to Ryne Sandberg. Orphaned away from this cluster of sculptures is one of Harry Caray, fittingly placed at the entrance to the center field bleachers where he would have felt most at home outside of the broadcast booth. His statue is also Wrigley’s most unique and, arguably, its creepiest; Caray’s upper half emerges out of a granite trunk from which the faces of fans pop out, as if from one of those cocoons seen in the Alien films.

Ditch the Car.

If you’re looking to catch a game at Wrigley Field via automobile, you be best advised to do your homework. The Camry Lot, a couple of blocks north of the ballpark, stands out as the most visible with 450 surface-level spaces, which you’ll likely need to reserve in advance. Beyond that, the parking choices surrounding Wrigley are virtually limited to scores of much smaller spots, mostly run by residents outside of their homes. Should you throw your hands up and surrender to the pursuit of parking, there’s a myriad of more public-oriented transportation options, most visibly Chicago’s famed elevated trains; the “L” is a “W” for many Cubs fans who take advantage.

If you have a little more money, the more convenient way to attend Wrigley Field is to grab a nearby hotel. Currently the most notable—and most expensive—choice is the Hotel Zachary, located right across Clark Street from Gallagher Way. Its architecture is inspired by the man for whom it’s named after, Wrigley architect Zachary Taylor Davis, and sits atop a series of establishments that range from a BBQ joint to a blues bar to a McDonalds. The added advantage of staying near Wrigley Field is that you can detour after the game to many of the area’s famed drinking holes that have provided longstanding lifelines to Cubs fans, places like Murphy’s Bleachers, Cubby Bear Lounge, Lucky Dorr’s, Sluggers, The Dugout and Rizzo’s Bar & Inn (no relation to former Cubs first baseman Anthony Rizzo).

Dystopian at first glance, this graffiti-strewn ticket booth at Wrigley Field is actually the work of celebratory Cubs fans using chalk to express their utter glee following the team’s 2016 World Series triumph—its first in 108 years. Happy vandalism this was not; the Cubs allowed it. (Flickr—Shutter Runner)

Everything is Finally Right in Wrigleyville.

By 2019, the 1060 Project was fully completed and Wrigley Field became new all over again. Even before the contractors left the ballpark, the upgrade was rubbing off on the fans and, especially, the Cubs themselves. The cutting-edge clubhouse and training facility was finished in time for the 2016 season, and the healthy aura it created put a spring in the step of a rising Cubs roster that had surprised the year before with an appearance in the National League Championship Series. Though the Cubs lost that series, the momentum from the overall 2015 campaign strongly carried into 2016, the 100th anniversary of the team’s first year at Wrigley Field. But none of the pre-planned centennial celebrations could match the performance of the Cubs, who performed as a team of destiny.

The 2016 Cubs had it all: A bright, curse-shattering general manager in Theo Epstein, a charismatic manager (Joe Maddon) who kept his players fresh with entertaining sideshows and dress days, rising young stars in slugger Kris Bryant, spry infielder Javier Baez and tenacious starting pitcher Kyle Hendricks, established stars in first baseman Anthony Rizzo, ace Jake Arrieta and closer Aroldis Chapman, the popular benchwarmer (back-up catcher and future Cubs manager David Ross) and a who’s who of VIPs seated amongst the 3.2 million who packed Wrigley Field, including actor Bill Murray and Pearl Jam front man Eddie Vedder. Even as they were burdened by the weight of 108 champion-deprived years fueled by a Billy goat curse, the Cubs seemingly could do no wrong—winning 103 regular season games, breezing through the NL playoffs and then, at long last, capturing the team’s first Wrigley-era World Series trophy with a come-from-behind, seven-game triumph over Cleveland.

The majors’ second oldest ballpark—Boston’s Fenway Park has it beat by two years—Wrigley Field has been invented, reinvented, altered, realtered and rejuvenated without really looking as if it’s changed terribly much, even with the necessary modern updates such as lights, luxury boxes and high-class underground lounges. The massive renovation given to the 100-year-old ballpark in the 2010s could very well allow it to exist through to its 200-year anniversary in 2114.

Yet some things will never change, whether it’s the wind, the ivy or the kids chasing home run balls down the neighborhood streets. The community that once led an uneasy coexistence with Wrigley Field now can’t seem to do without it. People move into the area knowing that they’ll be able to enjoy the presence of Wrigley Field, the Cubs and their vibrant fan base as much as they will tolerate it.

This is the grand bargain that Cubs and their neighbors have made. And why not? After all, you can’t call it Wrigleyville if there’s no Wrigley Field.

Chicago Cubs Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Cubs, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.