The TGG Interview

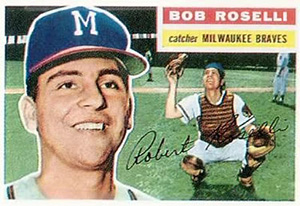

Bob Roselli

“Every member of the team got a brand new car, a Desoto, and all the gas we needed. And since it was a beer town, they gave us free beer—enough to keep your refrigerator stocked…They stopped me on the street and treated me like an old cousin they hadn’t seen in 20 years.”

Bob Roselli was a catcher for the Milwaukee Braves and the Chicago White Sox from 1955-1962. Born and raised in San Francisco, he missed the 1954 season and most of 1955 due to military service in Korea. Following his discharge, Roselli played in parts of three seasons with the Braves as a backup for Del Crandall (1955-56, 1958), and later joined the Chicago White Sox to help Sherm Lollar for two years (1961-62). Following his career in the majors, Roselli played for the Triple-A Hawaiian Islanders in 1963, his last year as a pro. After retiring, he worked as a salesman and also coached youth baseball teams. Roselli died in Roseville, California, at the age of 77 in 2009.

Bob Roselli was a catcher for the Milwaukee Braves and the Chicago White Sox from 1955-1962. Born and raised in San Francisco, he missed the 1954 season and most of 1955 due to military service in Korea. Following his discharge, Roselli played in parts of three seasons with the Braves as a backup for Del Crandall (1955-56, 1958), and later joined the Chicago White Sox to help Sherm Lollar for two years (1961-62). Following his career in the majors, Roselli played for the Triple-A Hawaiian Islanders in 1963, his last year as a pro. After retiring, he worked as a salesman and also coached youth baseball teams. Roselli died in Roseville, California, at the age of 77 in 2009.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On the 1955 Milwaukee Braves:

“The team moved there from Boston, so we were the new thing in town. Oh man, did they treat us right. Every member of the team got a brand new car, a Desoto, and all the gas we needed. And since it was a beer town, they gave us free beer—enough to keep your refrigerator stocked. I wasn’t obviously a starter, but the fans didn’t seem to care. They stopped me on the street and treated me like an old cousin they hadn’t seen in 20 years. It was great. And of course, we had a good team, so that helped quite a bit.”

On Encountering Racism:

“Being from California it was shocking when I saw how our black players with the Braves were being treated in some of these cities in the South and in certain parts of the Midwest. In California, we pretty much treated everyone the same, but in other parts of the country racism was prevalent everywhere you went. When we were traveling, we had to drop our black teammates off in the colored part of town, which I thought was pretty ridiculous. My black teammates (Hank Aaron, Bill Bruton and Wes Covington) were staying in a crappy little place at the outskirts of town and we were at the best hotel downtown. They never ate with us on the road and they had to use a different bathroom, so it was a real wake-up call from a young kid from California, believe me. I felt really bad for the way these guys were treated and there were many times when I had to bite my tongue.”

On the Tough Pitchers of his Day:

“I faced Bob Gibson, Whitey Ford, Frank Lary, Jim Bunning, Ralph Terry and Mudcat Grant—all the top pitchers of that period, and Gibson was by far the best pitcher I ever saw, without question. When he was on his game, which was most of the time, he was unhittable. I don’t think the Cardinals’ catcher Tim McCarver called the game—Gibson sent him the signals and Gibson called his own game. The catcher could just sit back there and be ready for what was coming. Ford was crafty; Lary would throw at you and he often did; Bunning had amazing control; Terry was solid and he won a lot of games because he had Mantle and Maris scoring a lot of runs for him and Grant was a battler who would throw harder as the game progressed.”

On Knocking Hitters Down:

“There was a lot of that going on in the ‘50s and ‘60s in baseball, more than today. If you upset the pitcher one way or another he would throw at you without hesitation. You did not even have to do anything; if the pitcher was in a bad mood, he’d set you down. One day, a pitcher for the Indians, I think his name was Barry Latman, gave up a home run to us when I was playing for the White Sox. I was the next batter and I could see that Latman was steamed. I knew he was going to throw at me, so I was ready. He missed me twice, because I was dodging the ball—and that made him madder. He finally got me on the shoulder with the next pitch. But, he was still mad about that home run, so he hit the next two guys too. He loaded the bases with guys he hit and then they took him out. After the game, I ran into Latman outside the clubhouse and I asked him why’d you hit me? Wrong place, wrong time, he said. Nothing personal, just another day at the office.”

On Early Wynn:

“He would knock down his own mother if she was crowding the plate. In batting practice, he would bean his own players if they dared to get a hit. If an opponent got a single off him, for example, he would sometimes throw over at first base with the intention of hitting the guy. He would throw at people and they weren’t even batting! He had quite a temper, but he was a great pitcher so no one ever said anything to him about it. For one, he’d probably kick your ass if you did. We gave him a wide berth, on and off the field.”

On the Aura of the Yankees:

“When they came to play us in Chicago, it wasn’t so bad. We felt like we had a chance against them in our stadium. But, when we played them in Yankee Stadium, there was a totally different vibe there. For one, the ballpark is unlike anything else and you get intimidated just walking in there. Then, the Yankees players had this attitude—I can’t describe it. They didn’t say anything because they didn’t have to. There was no trash talking or bench jockeying—none of that. They just had this air about them and their message came across loud and clear. They were very businesslike and you couldn’t help but being very impressed by that team. By the time you looked up and realized where you were—they were already sweeping you and it was over. A lot of teams would come into New York thinking they were all that, only to get beat. So they’d run home with their tails between their legs, realizing there was somebody much better than they were.”