The TGG Interview

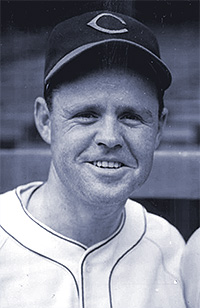

Eddie Carnett

“One day, we went to the Valley Forge Hospital in Philadelphia with all of the players from the White Sox. Some of the soldiers there were back from Normandy and I never seen such a bloody mess…When I was leaving that hospital that day I thought, war is hell. I can still see those kids like it was yesterday.”

Eddie Carnett played left field and pitched for three different teams from 1941-45. Nicknamed “Lefty,” Carnett entered the majors in 1941 with the Boston Braves, playing in two games before joining the U.S. Navy, where he served the next two years during World War II. After his discharge, he played for the Chicago White Sox (1944) and Cleveland Indians (1945). In a three-season career, Carnett posted a 3.40 earned run average with four strikeouts and three walks over 5⅓ innings in six pitching appearances. He did not have a decision. At the time of this interview, Carnett was 98 and was recognized as the third oldest ex-major leaguer as well as the oldest living former member of the White Sox and Indians. He died in November 2016, just a month after his 100th birthday.

Eddie Carnett played left field and pitched for three different teams from 1941-45. Nicknamed “Lefty,” Carnett entered the majors in 1941 with the Boston Braves, playing in two games before joining the U.S. Navy, where he served the next two years during World War II. After his discharge, he played for the Chicago White Sox (1944) and Cleveland Indians (1945). In a three-season career, Carnett posted a 3.40 earned run average with four strikeouts and three walks over 5⅓ innings in six pitching appearances. He did not have a decision. At the time of this interview, Carnett was 98 and was recognized as the third oldest ex-major leaguer as well as the oldest living former member of the White Sox and Indians. He died in November 2016, just a month after his 100th birthday.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On Stars he Befriended:

“I knew a lot of Hall of Famers, but at the time they were just really good players on the way up. I liked sharing my knowledge with them and that’s why I taught Warren Spahn his pick-off move and showed Bob Feller how to throw the slider. The other players asked me—why are you helping those fellas? And I told ‘em because that’s just the way I am. Some of the veterans thought if you helped a rookie or a young player, then later they might take your job—but my attitude is if they’re good enough to take it, go at it, boys!”

On Playing Baseball During World War II:

“We had a great team during the war and in fact, we beat every big league club we played. Our manager was Mickey Cochrane and he ran the team just like a major league squad. If you weren’t giving 100% he would let you know. Playing ball during the war was a cherry job and if you did not want to do it, Mickey would find someone else and he made that clear. One day, we were playing an exhibition game and Schoolboy Rowe was scheduled to pitch, but he started complaining that it was cold. Cochrane gave Rowe a dirty look and said ‘It’s pretty warm over in the South Pacific’ and Rowe got the point right quick. ‘Give me the damn ball skip!’ Rowe said and ran out to the mound without another word.”

On a Hospital Visit he’ll Never Forget:

“We went around the country and played exhibition games in front of some big crowds and we visited hospitals in some of the cities. One day, we went to the Valley Forge Hospital in Philadelphia with all of the players from the White Sox. Some of the soldiers there were back from Normandy and I never seen such a bloody mess. One injured kid loved Hal Trosky. The nurse told us that he had both eyes shot out. Trosky was in a batting slump at the time, and the kid got up and said, ‘I can see ol’ Hal Trosky now.’ He started imitating Trosky’s stance, and you could see that the whole scene was rattling old Trosky. Then he told the blind kid, ‘It takes a blind kid to tell me what I’m doing wrong.’ That poor soldier wasn’t worried about his eyes; he was more concerned about Trosky’s stance. It was tough and most of us were crying because most of those guys who came back, they were shot up real bad. When I was leaving that hospital that day I thought, war is hell. I can still see those kids like it was yesterday.”

On How Baseball May have Saved his Life:

“I was in the Navy and the Commodore of our Naval District wanted us to go around and play exhibitions. One of the first places we went to was Fort Dix and we played a series of exhibition games there. There were a couple of soldiers there who called me a draft dodger because I was playing baseball. The Army guys told me not to worry about them and then they threw them out of the ballpark. I’ll tell you how to stop war. Take guys like me, 80-90 years old and put us in the service, on the front lines, and after four or five shots, you know what we’re going to say, ‘What in the hell are we doing here?’ Old people start wars and then they make the young people fight them, but it ain’t even close to being fair.”

On Carousing and Getting Old:

“I never got stupid about drinking, unlike quite a few of my teammates. No, I won’t give you any names, because, hey—they’re all gone anyway. I’d have a beer and it would taste fine, but then I would stop. A lot of my teammates were out late chasing the young girls, but I was married (Marilee and Ed recently celebrated their 75th anniversary) so I wasn’t interested in that. They would be dragging the next day and I’d ask them, was it worth it? And most of the time they said hell, yes! Living this long means I don’t have to go to all these silly reunions (laughs). Do I think I’ll live to be 100? I sure hope so, but don’t rush me.”

On a Near Fight with the Ol’ Professor:

“It was a chilly day in Boston and all of a sudden (Casey) Stengel looks at me and says get in there, you’re pitching. He was sending me in against the Giants without warming up, so I wasn’t ready and I sure didn’t know why. So, I walked the first two batters and Stengel took me out of the game, shaking his head and showing me up. So, I wasn’t a happy camper, to say the least. In the clubhouse we got into yelling at each other and I said some things and he said some things that weren’t nice and we had to be separated. Well, that did not play well with Casey or the team, so I got sent back down to the minors the next day. Was it fair? Hell, no!

Then, five years later, I got the job managing the Vancouver Capilanos in the Western International League. The team was in Oakland playing the Oaks at that time and who was their manager? That’s right, Casey Stengel! He heard the news and hunted me down in the hotel where we were staying. We had a fairly nice conversation and then he asked me about that day in the Boston Bees clubhouse. ‘Were you really going to try and beat me up?’ Stengel asked, and I told him yes. ‘Well, I’m sorry it didn’t work out in Boston,’ he said. ‘I don’t have any resentment toward you.’ And that was that—forgotten and forgiven.”