The TGG Interview

Jerry Reuss

“When I was with the Cardinals and the Pirates, we would all go out to dinner together on a regular basis. But on that Dodger team, sometimes they’d show by at the same restaurant for whatever reason, but they wouldn’t sit together and even acknowledge each other, like they were complete strangers. That was new to me.”

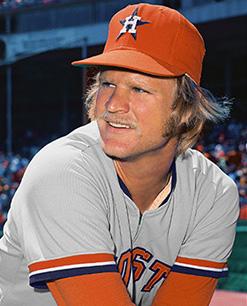

Jerry Reuss as a member of the Houston Astros. Note the mustache; it’s the reason he got traded from St. Louis. (Photo courtesy of Doug McWilliams)

Jerry Reuss was a major league pitcher for 22 years, playing for the St. Louis Cardinals, Houston Astros, Pittsburgh Pirates, Los Angeles Dodgers, Cincinnati Reds, California Angels, Chicago White Sox, Milwaukee Brewers and finishing back with the Pirates. He won 220 games, threw a no-hitter, played in two All-Star games and pitched in the World Series for the Dodgers. Since his retirement as an active player in 1981, Reuss has been working as a broadcaster for several networks including ESPN, and he recently wrote his autobiography, Bring in the Right-Hander.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On the Moment he Realized he Could Play in the Majors:

“It happened a few times definitely. It wasn’t like I thought I could play at the major level, but there were several moments where I thought about the fact that I might have something here. I knew I had some ability that was possibly more than the average player or even more than the better guys I was playing against at each level. I was always comparing myself to whatever was going on at the time. When I got to the rookie leagues, I took a look around and I was impressed, because there were a lot of really good players there. Some of them had a curve ball that was equal or better than mine and then there were the hitters who could hit the ball over the fence in batting practice. I said, wow—these guys can play! I hope I made the right decision by signing a professional contract instead of going to college, I thought—this could be tough. Life in general eliminated a lot of these guys from the competition and I learned that rather quickly. Many of them lost interest in the game for a variety of reasons; they got hurt, they were homesick. Some of them realized that this wasn’t the life they wanted and a lot of them couldn’t handle the schedule of playing every day—any number of reasons. It wasn’t that they got cut or released—they eliminated themselves and it had nothing to do with talent. But, I stayed with it and many of my teammates did too.

I made it through single-A and I saw a lot of guys age out, even though they were still in their early or mid-20s. At every level, players opted out for so many different reasons. At Class-AA, it got very interesting, because it was a mixture of former MLB players trying to get back there mixed in with a bunch of hungry young prospects like me. Just by being there, the older players would teach the prospects how to play the game, so it’s an unusual dynamic, but in my case it worked out well.

The easiest part of the journey is getting to the majors, but the hardest part is staying there. In Little League, I dreamt of being a major leaguer, but those were simply the dreams of an eight-year-old. In high school, there were times when I dominated and I figured the future was mine. But, I was always asking myself—how will I do against players from another state in a different league? You never really knew how you stood, so you just had to keep plugging away to prove who you were and where you deserved to be in the game. I played parts of 22 seasons in baseball, and every time I put on that uniform, I told myself how lucky I am to be playing in the big leagues.”

On his First Game:

“The first MLB game I ever attended was at the old Busch Stadium when I was seven. I looked around and saw that this is what I want to do. In the car on the way home I told everybody in uncertain terms that I was going to be a major league ballplayer. My brother (riding shotgun because he was the eldest) laughed at me and said, ‘We all want to be major leaguers too, but don’t you know what the odds are-maybe one in a million to make it?’ I paused and said and in a rare moment of clarity, ‘There’s got to be one, so why not me?’ I made a commitment to myself at that moment and as a result my life changed, because now I had direction and I knew what I wanted to do. Now I could script my future.”

On Being Traded for a Mustache:

“Some people don’t believe it, but yes—I was traded from the Cardinals to the Astros because of my mustache and that’s a fact. The team’s owner, Mr. Busch, said he didn’t like mustaches and he wanted me to shave it off. Busch was known for getting mad at a player and then he would settle down later, but he had this thing about mustaches and I guess it became a real issue. People thought it would blow over, but it didn’t and the team’s general manager Bing Devine was forced to trade me to the Astros. I was crushed about being traded, because I grew up in St. Louis and that was my team.”

On Pitching in the Houston Astrodome:

“It was a big ballpark and the ball didn’t really carry much under that dome, especially if it was hit to left center or right center field. And it always seemed real dark in the Astrodome for some reason. As time went by, the turf became uneven. I know why they built indoor stadiums and they were popular back then, but I like the newer stadiums today, because they look like baseball stadiums.”

On Being Houston’s Workhorse in 1973:

“I started 40 games, which is still a record for the Astros and I don’t think it will ever be broken. Our manager Leo Durocher decided to go with a four-man rotation, so I pitched almost 300 innings that season. I don’t know why, but maybe it went back to his days managing the Dodgers and Giants, when he had four able-bodied starters who could give him 200-250 innings every year and I was the only pitcher on that Astros staff that could handle that kind of load. I began to feel it toward the end of the season, but Leo still had me throwing batting practice between starts anyway—like they did back in the 1940s. The coaches weren’t happy about that and at one point they said no more throwing batting practice, to save my arm, you know. They didn’t have 100 pitch counts back then, in fact I never really recalled anyone ever counting pitchers even though I’m sure they probably did.”

On Leo Durocher:

“The Astros got rid of Harry Walker because they said he couldn’t communicate with the players. But then they replaced him with Leo, who lost the team even worse. Durocher rubbed some people the wrong way and I was one of them. He would do things like play poker with the same 3-4 players and they played for money, sometimes a lot of it. These players loved to play cards, but they were no match for Leo—they just weren’t as good as he was. He would take their money and I thought, wow that’s not right. That didn’t sit well with me.”

On Being Traded to the Dodgers:

“I was happy in Pittsburgh, but when they told me the Dodgers wanted me, I thought about it for about a minute or so and before deciding. Southern California has great weather all year-round; they play on a grass field; the Dodgers are perennial winners—I like everything about them! Every time I went to a new team I got paid a little more, but uprooting and moving each time wasn’t fun. You get attached to a city and a team when you’ve been there for any amount of time, so being traded worked out well financially for me, but it was tough each time for the reasons I mentioned.”

On Tommy Lasorda and the Team Atmosphere in Los Angeles:

“Tommy joked with all the players and hung out in the clubhouse and that was his style and it worked for him. He was chummy, but the team wasn’t. When I was with the Cardinals and the Pirates, we would all go out to dinner together on a regular basis. But on that Dodger team, sometimes they’d show by at the same restaurant for whatever reason, but they wouldn’t sit together and even acknowledge each other, like they were complete strangers. That was new to me, but it must have worked because those Dodger teams were all winners and highly professional on the field.”

On his Photography of Stadiums:

“I always had an interest in photography. In fact, whenever a Topps photographer showed up during spring training or if I spotted one during the season, I would always strike up a conversation and ask him about the camera, how to frame the shot, what photos seem to sell, the most interest and how to approach the subject that you’re shooting. I never really did anything about it, until one day between the 1988 and 1989 seasons when I realized that my baseball career is coming to an end. In fact, I didn’t even know if I was going to be playing in ’89 at all. This could be it, I thought.

So, I knew I had a ton of great memories, but I didn’t have anything in hand to remember some of the places I had visited. I realized I can’t do anything about all of the things that have already happened, but I can do something now. So, I decided that if I do get to play this year, I’m going to have a camera with me. So, I started coming to each ballpark early and taking pictures of these stadiums, because history told me that they were not going to be around forever. So, that’s why most of my photos are from 1988. I also took some in 1989, mostly of the ballparks I missed the year before. During the very brief time when I was in the majors in 1990, I took even more.

I realized that I had access to parts of these stadiums just by the fact that I was wearing a uniform. Once security saw me in my uniform, they just let me go anywhere I wanted. They would let me move the batting cage over to get better shots and they said okay to requests like that. Some of the grounds people seemed to be genuinely interested in some of these stadiums and I developed relationships with them through the photos.

I like some of the photos that I took during that time, but I’m not crazy about all of them. I was constantly honing my techniques and trying to get better and better photos. I’m proud of some of them, including the ones I took of Exhibition Stadium in Toronto. For some reason, those have become popular online and really gained a lot of attention. Over the years, I’ve received a bunch of emails from people thanking me for taking these pictures, which is very satisfying. People share their stories with me, about how their father took them to this or that stadium and they’re enjoyable to read. It just goes on and on.

Looking back now, I can realize that this project was a monumental success and now I know that these will be part of my legacy. All people have to do is go online and take a look at them and get lost for a couple hours, which is great. Based on all of the hits (approaching 1.7 million views) I’ve received on Flickr, I can see that people like these photos.

Editor’s Note: In our ever-expanding Ballparks section, you’ll see a good number of Jerry Reuss’ ballpark photos. We thank him for his permission to use these images.