The TGG Interview

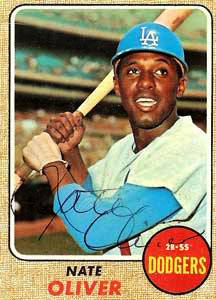

Nate Oliver

“Marichal was having some initial problems getting into the Hall of Fame. And it was Roseboro who made the phone call to the powers-that-be and said ‘are you kidding, this is one of the greatest pitchers the game has ever seen.’”

Nate Oliver was a likable but light-hitting infielder for the Los Angeles Dodgers in a time when they could get away with light-hitting players, thanks to their pitching. Oliver claims the Dodgers he played for were not arrogant as some suggested—just confident.

Of all the retired major league baseball players I’ve interviewed throughout the years, few have made me feel as comfortable as Nate Oliver. A soft-spoken and extremely articulate man, I have talked to him on several occasions after meeting with him initially in early 2005. His stories of his years as a player and a coach are both fascinating and candid.

Nate is the son of Jim Oliver Sr., who played in the Negro Leagues. James Oliver Field in St. Petersburg, named after Nate’s father, was the first field to be refurbished under the Tampa Bay Devil Rays Field Renovation Programs. Nate’s brother, Jim, also played professional baseball.

Nate often bounced around between the minors and majors throughout his playing career, in large part because he couldn’t break free of the Mendoza Line (.200) and possessed very little power (two home runs in 954 career at-bats). He played five of his seven big league seasons for the Los Angeles Dodgers, and although the Dodgers reached the World Series in three of those five years, Nate made just one appearance in the Fall Classic, during the 1966 Series as a pinch-runner.

After his final season in the majors, playing for the 1969 Chicago Cubs, Nate became a low-level minor league manager in such diverse spots as Palm Springs, Daytona and Saskatoon. Most recently, Nate was a bunting instructor in the Chicago White Sox’ organization.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On former Cubs teammate Ron Santo:

“I cannot believe this man is not in the Hall of Fame. If you look at what Ronnie has done—he won eight Gold Gloves, he was in six or eight All-Star games, he has 342 home runs, he might still have the best fielding percentage of any third baseman, I think he still holds that record. He was no average Joe. He was an outstanding player. He was our team captain. I don’t know what else they want the guy to do.”

On Cubs fans:

“Oh, Jesus. Everybody always talks about the Cardinals fans, the Yankees fans, the Red Sox fans, but the Chicago Cubs fans to me were the very best. They were the greatest. Until this year (2004) I had never heard them boo one of their own players, but this year I did hear them boo Sammy (Sosa) which was sad. I thought I heard them boo Sammy this last season. But, as a rule, they never booed their own players. They were just unbelievably supportive. But, I don’t need to tell you that, because wherever you go, you see Cubs fans. It’s like it was with the Red Sox fans. You’d see them everywhere—praying, dreaming, hoping. And now that the Red Sox have won it all, people are starting to say that it must be the Cubs’ time. If they don’t win it within the next six years, it will be a century of no championships for the Cubs.”

On the Dodgers of the 1960s:

“The Dodgers were known around the league as a very arrogant team at that time. People said they were very conceited, but it wasn’t that at all. They were just really confident and people misinterpreted that as arrogance. It was instilled in them from the first day with the organization and the people who played there respected the tradition and fostered it. Every year, there was only goal and that was to get to the World Series. Everything else was second best.”

On the Roseboro-Marichal fight:

“We had Johnny Roseboro, probably the most respected guy on that team, because he was such a tremendous student of the game and when he spoke, regardless of who was in the room, everybody listened, because everything he said was profound. Marichal and Roseboro were probably two of the most respected men in baseball. They were also the two most competitive people in sports, period. They were also two of the nicest guys you’d ever want to meet, in terms of being human beings and in terms of being gentlemen. If you recall or have heard the story, because of that fight and the fact than Juan hit Johnny with the bat, Marichal was having some initial problems getting into the Hall of Fame. And it was Roseboro who made the phone call to the powers-that-be and said ‘are you kidding, this is one of the greatest pitchers the game has ever seen.’ That was an isolated incident between two clubs who did not like each other and it was part of that rivalry between the Giants and the Dodgers.”

On the self-managed Dodgers of 1963:

“Junior Gilliam was essentially the manager on the field. He had no problem taking on that role. If a pitcher was in trouble out there and something was going awry, Gilliam would step up immediately and act as the manager. Our pitching coach Red Adams would only come running out if he saw something mechanically wrong with the pitcher. Because if a pitcher fell behind, if he was wild or his concentration level wasn’t there, it would be Gilliam that would call time and walk over to the mound. All our manager Walter Alston had to do was sit there and push buttons, because we had so many guys like Gilliam, Maury Wills, Jim Lefebvre and Roseboro who were such tremendous students of the game of baseball.”

On teammate Maury Wills:

“He was so valuable to that Dodgers team, because when he got on base, everybody knew he was going to steal. You can’t imagine how exciting it was to hear 55,000 people at Dodger stadium yelling ‘Go! Go!’. If 55,000 people knows he’s going to go, then you know the opposing team certainly knows it. But, it didn’t matter, because they couldn’t stop him. He was going to go within the first three pitches; they just didn’t know when. What Wills did was create havoc for the other team. He got more fastballs for me and anyone else who batted behind him in the lineup. He also drew the infielders in because of his speed. And he kept the defense on edge at all times, which basically means that they were distracted and out of position. As a result, ground balls that would normally have been routine infield outs are now going through as base hits, because they’re defending Wills and not defending the hitter. He did so many things just by being so aggressive and by being the greatest base stealer I ever saw.”