The TGG Interview

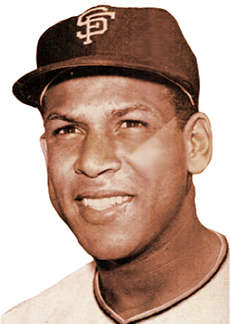

Orlando Cepeda

“Buddhism could have helped me because I did so many bad things during those years. I stayed up all night every night to go to clubs and dance. If I had become a Buddhist during my baseball career, I believe I would have batted .300 and hit 500 home runs.”

I was doing my daily walk at Lake Chabot in Castro Valley, CA when I ran into a gentleman who caught a trophy-sized catfish. We talked about his catch and somehow, he mentioned that his name was Orlando Cepeda. “Wow, your parents must be big fans of the Baby Bull?” He said, “Yes—in fact I am the Baby Bull’s youngest baby!” So, I told him about This Great Game and asked if there was any chance that I could interview his father. He said yes, and one month later my phone rang. It was Orlando, Jr. saying hello and then putting his famous dad on the line.

Nicknamed “The Baby Bull” Orlando Cepeda was a powerful slugger with a .297 lifetime batting average and 379 career home runs. He played for the San Francisco Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, Oakland A’s, Boston Red Sox and Kansas City Royals. After his 1974 retirement, Cepeda suffered from financial, marital, and legal troubles culminating in a 10-month prison term for marijuana smuggling. Despite his impressive career, Cepeda’s election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame took more than two decades to happen. In 1999, he became a Buddhist; “I slowed down, got to know myself better, and became a different person,” he said.

As told to Ed Attanasio, This Great Game

On Starting Out as a Batboy:

“A man named Pete Zorilla owned the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican Winter League. I got a job as the Crabbers’ batboy and began practicing with the team. I was 16 years old and felt like I was on the top of the world. In 1954, Zorilla got me a tryout with the New York Giants in Florida. It was the first time I ever left home, and I was nervous, but I must have done well because the Giants signed me. They gave me a $500 signing bonus, and it looked like a million to me! When my father died a few days later, I used the $500 to pay for his funeral.”

On his 1958 Rookie Season:

“They had a lot of prospects and we all went to Spring Training together in 1958. (Willie McCovey, Felipe Alou, Leon Wagner, Willie Kirkland, Jim Davenport, and José Pagán were all there.) Whitey Lockman was their starting first baseman, but I started hitting home runs, and made a few good plays at first. Lockman said, “This kid Cepeda is going to end up in Hall of Fame.” My first game as a Giant was against the Dodgers at Seals Stadium, in the first major-league game ever played in California. I played first base and batted fifth, and we shut them out 8-0, with Rubén Gómez on the mound. I also hit my first home run against Don Bessent. It was a good year (.312 with 25 home runs and a league-leading 38 doubles) and I won the National League Rookie of the Year award that year.”

On Playing in the City by the Bay:

“Right from the beginning, I fell in love with San Francisco. We played a lot more day games then, so I usually had at least two or three nights a week free. Every Thursday, I would always go to the Copacabana to hear the Latin music. On Sundays, right after games, I’d go to the Jazz Workshop for the jam sessions. At the Blackhawk, I’d listen to Miles Davis, John Coltrane. My roommates were Felipe Alou and Rubén Gómez, but they didn’t go out the way I did. Felipe was quiet, and Ruben just liked to play golf as much as he could, so I’d usually go out by myself.”

Two Great First Basemen:

“When Willie McCovey came up, everyone knew he was going to be great. He came out of the minors strong but then he started struggling, especially against left-handed pitchers. They wanted both of us in the lineup every day, but I wasn’t crazy about playing in the outfield. I know I could’ve played left field, but I was only 21 at that time and a little stubborn. I was proud and felt like I deserved playing at first, so it got in my head a little bit. But it never affected my hitting. (Giants manager Bill) Rigney told some reporters I was a better athlete than Willie and that’s why I could play the outfield. So, I told him I’m your first baseman and not a left fielder. McCovey got sent back to the minors in 1960, so I got my job back for a while until he came back. Then In 1962, Al Dark (the new Giants manager) moved McCovey to left field and I was back at first base, where I belonged.”

Dark Days:

“I don’t have great memories of my last years in San Francisco. Alvin Dark didn’t like me and I didn’t like him either. He benched me and fined me and we never got along. To be honest, I don’t think he liked black and Latino players. Dark thought baseball was like the military. He was always telling us to speak English and turn down our music. Dark treated me like a child and really didn’t understand his Latin players. Latins are different, but Dark did not respect our differences.”

On Getting Traded:

“I felt real good going into Spring Training in 1969, hoping for a comeback year with the Cardinals. When they told me I was being traded to Atlanta for Joe Torre, I was surprised. I was happy playing for the Cardinals. I was a little concerned about playing in the South, but overall, it was a good experience. I got to play with my buddy Felipe Alou and Hank Aaron, and it was a good team. We had second baseman Felix Milan, third baseman Clete Boyer, and outfielder Rico Carty with some young players coming up like Ralph Garr (age 23), Darrell Evans (22), and Dusty Baker (20). We won the division in ’69, but lost to the Mets in the playoff, even though I hit more than .400 in the series and hit a homer off of Nolan Ryan.”

On the New DH:

“In 1973, the American League said they were going to start using a designated hitter, and it could add some time to my career. The Red Sox could see that I could still hit. I hit 20 home runs and never played one game in the field and then I got the Designated Hitter of the Year award for being the best DH. In 1974, I got released and my career was almost done. I signed with the Kansas City Royals and played a little in Mexico before retiring.”

The Hall of Fame Finally Calls:

“I did not get in right away, but in 1999 they called and it was great. I had to wait 25 years, but it was okay because I wasn’t ready to get in before. I still had a lot of work to do on myself. The Giants also retired my number that year. In 2008, the Giants made a statue of me that’s right outside the stadium. When things like this happen to you, that’s when I say to myself, ‘Orlando, you’re a very lucky person.’”

On Buddhism:

“II retired in 1974 and then things got worse. I was bitter and resentful about a lot of things. I was blaming everybody but me for some things that had gone wrong. But when I started practicing Buddhism, I found out that I was the main problem. With Buddhism, you learn the laws of life, because life is based on cause and effect. The chanting helps me, because when I’m chanting, I don’t listen to anything else. I just focus. Buddhism could have helped me because I did so many bad things during those years. I stayed up all night every night to go to clubs and dance. If I had become a Buddhist during my baseball career, I believe I would have batted .300 and hit 500 home runs. The reason I didn’t play ball was because I wanted to party every night. I never drank that much, but I’d smoke weed. The next morning, I didn’t want to go to the ballpark. If you have your common sense, you know you’re a ballplayer. You know how to take care of yourself, but I had other things to do.”