THE YEARLY READER

1917: Clean Sox

While America enters the Great War and pressure is put upon owners and players to do their part, the Chicago White Sox prevail in the World Series with many of the same players who will severely taint the game’s reputation two years later.

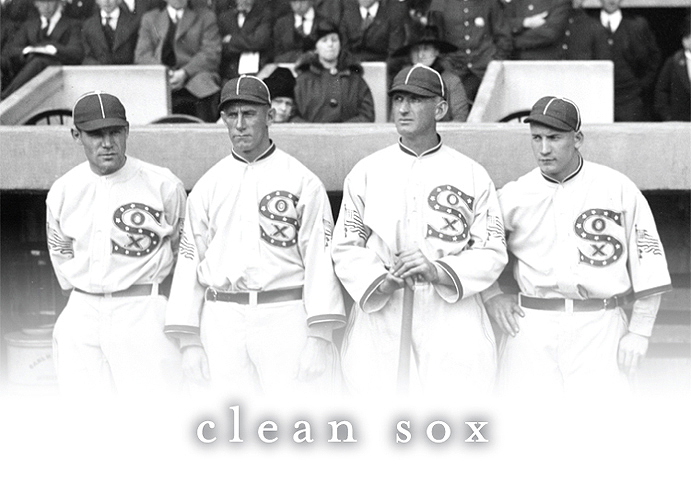

Joe Jackson (second from right) poses with Chicago White Sox teammates wearing a patriotic variation of their uniforms in honor of American armed forces fighting overseas. (The Rucker Archive)

There were no accusations of Heinie Zimmerman intentionally throwing wide of first base to allow a runner on. No one squawked about Dave Robertson muffing a fly ball by design, placing a second runner on. Nothing was implied that home base purposely wasn’t covered during a pickle, bungling up a rundown that allowed a crucial run to score.

Collectively, all of the above made for one big gift from the New York Giants.

And the Chicago White Sox said thank you very much.

The two errors and the botched rundown opened the door for a fourth-inning White Sox rally in Game Six of the 1917 World Series, leading to three unearned runs and a fourth straight Series defeat for the Giants.

Piloted by third-year manager Clarence “Pants” Rowland, the White Sox featured the same cast of performers which, two years later, would evolve itself in one of American sports’ ugliest episodes: The Black Sox Scandal.

For now, the Chicago ballplayers who would toss away a World Series in 1919 appeared to be playing to the best of their ability. Ironically, whether some of their opponents gave it their all would eventually become a matter of suspicion.

Owned by the “Old Roman,” Charles Comiskey, the White Sox had always been one of the American League’s steadiest franchises, historically strong on pitching while weak on hitting. But after winning the World Series in 1906, the team began to fade further and further away from the top, its impotent lineup providing less and less wonder.

That changed in 1915 with the addition of two top-flight batting superstars. Comiskey purchased second baseman Eddie Collins via Connie Mack’s fire sale, and later in the year traded for Cleveland outfielder “Shoeless” Joe Jackson.

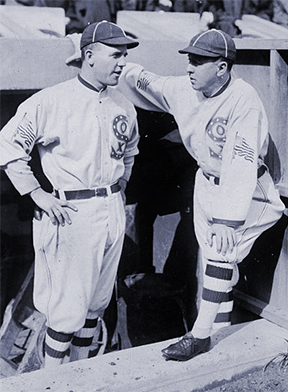

Eddie Cicotte, shown at left with White Sox manager Pants Rowland, led AL pitchers in 1917 with 28 wins, a 1.53 ERA and a .248 on-base percentage allowed.

The improvement within the Chicago roster didn’t stop with Collins and Jackson. Buck Weaver was slowly yet surely asserting himself as one of the finest third basemen in the game, and with each season was edging closer to a .300 batting average. Catcher Ray Schalk was small in height but built like a tank—with a spirit to match, aggressively barking confidence into his pitchers. Happy Felsch, a young outfielder quickly developing into a solid power hitter, also possessed great command and range in center field.

For 1917, the White Sox picked up two more pieces of the puzzle for their everyday lineup. Chick Gandil arrived from Cleveland as a talented first baseman with a reliable bat; and a 22-year-old rookie from San Francisco named Swede Risberg became an immediate starter at shortstop.

On the mound, Chicago was as vaunted as ever. Veteran shineball pitcher Eddie Cicotte was complemented by spitballer Red Faber and 24-year-old Lefty Williams, who was found languishing on Detroit’s staff and immediately made an impact for the Sox.

BTW: Cicotte’s shineball was named as such because he would dirty the ball on one side and rub the other half completely clean; the contrast created from the ball’s rotation was known to cross up hitters.

If the White Sox hadn’t quite yet reached their prime, they were close. They nevertheless petrified opponents, who witnessed the Sox explode through the 1917 season.

Despite winning 16 of 17 games early on to stake their claim at the top, the White Sox endured through a tough summer race with the two-time defending champion Boston Red Sox. Finally in late August, Chicago broke free and breezed to the finish, taking the pennant by nine games over the Red Sox.

BTW: The Red Sox’ lack of a strong offense exhausted itself out of first place. Pitchers Babe Ruth and Carl Mays—with 24 and 22 wins, respectively—weren’t enough to prolong Boston’s dynasty.

Chicago’s road to 100 wins was truly a team effort. Collins (with a .289 batting average) and Jackson (at .301) endured low numbers by their standards, but others picked them up, especially Felsch (.308, 102 RBIs). Williams (17 wins, eight losses) and Faber (16-13 with a 1.92 earned run average). But it was Cicotte whose numbers stood out the most; the 11-year veteran overwhelmed all expectations with an AL-best 28 wins and 1.53 ERA.

Surviving his team’s wild rollercoaster ride through the 1916 National League season, New York Giants manager John McGraw got his team to win—and keep winning—during the new season.

Retooling his team through the severe ups and downs of the year before, McGraw felt content going into 1917 with the roster that had won him 26 straight at the end of 1916. As usual, his intuition paid off.

More to McGraw’s pleasure, the rebuilt Giants continued to reflect his pugnacious, brawling personality. In a spring training exhibition against the Detroit Tigers in Dallas, second baseman Buck Herzog and the Tigers’ Ty Cobb got into a verbal contest after Cobb had reached base; it turned physical after Cobb stole second. The two were separated, but only until nightfall when they squared off again in Cobb’s hotel room. Herzog, a former boxer, took a pounding from Cobb, who himself would have been a very good pugilist had he taken up the sport.

BTW: The crowd at the exhibition game reportedly cheered Cobb, in part because Herzog was of German descent—a point of scrutiny during the Great War.

When the 43-year-old McGraw learned of Herzog’s condition the next morning, he intercepted Cobb in the hotel lobby, and baseball’s two titans of wrath had to be restrained from starting a mano-e-mano that would have doubled worldwide the publicity already generated.

The Giants’ bullying worked; Cobb refused to show up for more exhibitions between the teams, and when the last of those games ended, Giants players fired off a wire to Cobb: “It’s safe to rejoin your ballclub now. We’ve left.”

McGraw himself became the object of controversy after the season had begun. Infuriated by a bad call that he felt had cost the Giants a victory in Cincinnati, McGraw charged at umpire Bill Byron—an umpire known for irritating players and managers by singing sarcastic rhymes about them within earshot—and slugged him in the mouth. The singing umpire’s lips were bloodied.

When NL president John Tener suspended McGraw for 16 days and fined him $500 for the incident, the belligerent Giants manager lashed back through the New York Globe, stating that Tener was biased toward the Philadelphia Phillies, with whom the Giants were in a fight with for first place. When McGraw later retracted his comments, he made new enemies: Those of the Baseball Writers Association of America, for whose written transcripts of McGraw’s statement were now being challenged as false. BBWAA representatives screamed at Tener, who recognized their power with the pen; McGraw was fined another $1,000.

BTW: McGraw could afford to pay the fine; he was in the first year of a five-year contract that paid him $40,000 annually, much higher than any player or manager in baseball.

McGraw got over the incident, served his time, and the Giants quietly pulled away from Philadelphia to claim the NL pennant. The second-place Phillies got 30 more victories out of Pete Alexander, but as a team they couldn’t match the dominance of the Giants.

BTW: With three straight years winning at least 30 games, Alexander became the last major league pitcher to date to notch 30 in consecutive years.

Individually, the Giants presented another healthy mix of talent. Dave Robertson led the NL in home runs (12) for the second straight year. George Burns and ex-Federal League superstar Benny Kauff were second and third in NL steals, with 40 and 30 respectively. And McGraw’s pitching staff performed by committee; seven different hurlers started at least 10 games. The de facto workhorse was Ferdie Schupp, who won 21 of 28 decisions.

Two of McGraw’s late-season acquisitions from the year before made major contributions. Third baseman Heinie Zimmerman led the NL with 102 RBIs; starter Slim Sallee won 18 while losing only seven.

The Giants and the White Sox appeared evenly matched for the World Series, and the first four games proved it. The White Sox took the first two games at Chicago’s Comiskey Park; the Giants rebutted by tossing two shutouts (by Schupp and Rube Benton) back at the Polo Grounds to even things up. After a sloppy 8-5 win by Chicago in Game Five, the Series returned to New York for Game Six.

While the Giants could not properly defend against Chicago baserunning in the World Series, they found that the White Sox could against theirs. Here, Bill Rairden is retired on the back end of a double play after attempting to bunt Art Fletcher home in Game Four. (The Rucker Archive)

Zimmerman, frustrated afterward, scornfully wondered if it would have helped to relay the ball to the only person standing near home plate—umpire Bill Klem.

Klem, upon hearing the comment, volunteered, “I was afraid he would.”

While the 1917 World Series appeared to be clean, 10 years later the question arose as to whether the White Sox had bought their way in.

In an outgrowth of the 1926 controversy in which Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker stood accused of fixing a 1919 regular season game, new information came to light regarding the 1917 AL pennant race. Swede Risberg and Chick Gandil, both participants in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, testified that White Sox players—and even Charles Comiskey—had anted up and paid off the Tigers to lay low for two straight doubleheaders against Chicago. The White Sox won all four games.

BTW: Risberg added that the St. Louis Browns were similarly funded to take it lightly against the White Sox.

In the ensuing cavalcade of hearings, those accused gave an innocent version of Risberg and Gandil’s story; that the White Sox had put together a pot of money to present to Tiger players—not as a bribe to lose, but instead as a gift for having swept Boston in an earlier series. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, tough on game-fixing but tiring of decade-old accusations, eventually ruled that the money probably was a gift; although he deemed it an act of wrong doing, it was not, in his opinion, criminal.

Even had White Sox players bribed others to get to the World Series—thus earning bonus shares for being there—they likely had their reasons. Comiskey had a reputation as one of baseball’s most notorious cheapskates when it came to paying his players. Even his promises for bonuses were left empty. Legend has it that Eddie Cicotte’s contract called for a $10,000 bonus if he won 30 games in 1917. Cicotte had never won 20 in any one season, so Comiskey figured the bait was a pipedream. But when Cicotte got to 28, Comiskey began to sweat and pressured Pants Rowland to “rest” Cicotte for the World Series rather than let him make his few remaining starts. And when White Sox players were promised extra “bonuses” by Comiskey for winning the Series, they discovered that the reward amounted to nothing more than champagne.

With the reserve clause giving Comiskey the power to pay what he pleased, there was little the players could do.

The prologue to the Black Sox Scandal had been written.

Forward to 1918: All Work or Fight and No Play Baseball scratches and claws to stay intact as World War I reaches its brutal apex.

Forward to 1918: All Work or Fight and No Play Baseball scratches and claws to stay intact as World War I reaches its brutal apex.

Back to 1916: A Test of Robins Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson takes on former pal and current foe John McGraw for the National League pennant.

Back to 1916: A Test of Robins Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson takes on former pal and current foe John McGraw for the National League pennant.

1917 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1917 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1917 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1917 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.