THE YEARLY READER

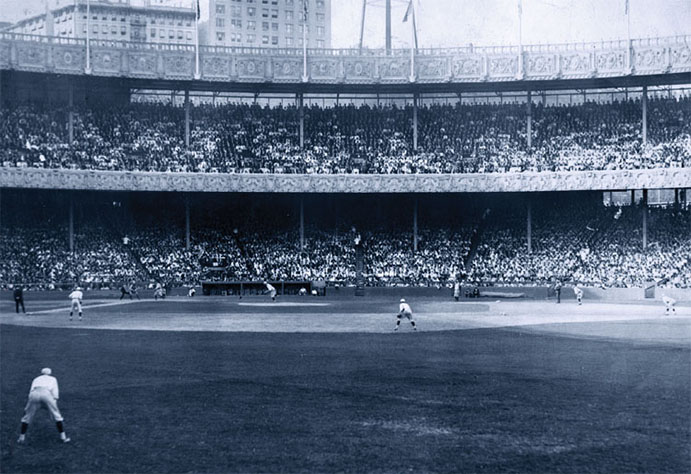

1921: See You at the Polo Grounds

The shared home field for both the New York Giants and New York Yankees takes center stage as both tenants battle it out in a close World Series.

The shared home field for both the New York Giants and New York Yankees takes center stage as both tenants battle it out in a close World Series. (The Rucker Archive)

Babe Ruth had been to the World Series before. But never as Babe Ruth, the Sultan of Swat.

The heroic Ruth of Fall Classics past was restricted to the pitcher’s mound, where he shined for the Boston Red Sox by hurling nearly 30 consecutive innings of shutout baseball. His staggering hitting talent had yet to be fully realized; he was a star to be sure, but not yet an icon.

Yet a year after his stratospheric achievement in belting 54 home runs, everyone wondered aloud whether Ruth could duplicate his remarkable showing of 1920 and bring the New York Yankees to the Series for the very first time.

The Polo Grounds, home for both the Yankees and their landlords, the New York Giants, was about to become a busy place come October.

There had been serious doubts about Ruth for 1921. People looked at his numbers for 1920 and put them into perspective with everything before—and therefore were convinced that Ruth had muscled together a one-time-only, phenomenal campaign that might be approached, but never repeated. On top of that, his overindulgence for the good life was, to many, a sure sign that his career was headed for a fast burnout.

Instead, Ruth was ready to prove that he had merely catapulted the levels of power hitting to a standard he would more than occasionally match for years to come.

The Bambino amazed anew, topping—not matching—his milestones of the year before. He broke his year-old home run record with 59, clipping the old mark with three weeks left in the season. Also erased was the career home run record, previously held by 19th Century “slugger” Roger Connor. At the age of 26, Ruth became the all-time home run king with his 138th career blast.

Ruth also broke existing records in runs batted in with 171, runs scored with 177, and total bases with 457; the latter two marks remain all-time records. Proving that home runs weren’t all Ruth excelled at, he finished second in the AL with 44 doubles and tied for fourth in triples with 16; his 119 extra base hits established a record also never since touched. Ruth’s .378 batting average was fourth best in the majors, trailing great names in Ty Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, and Harry Heilmann. He even stole 17 bases to share the Yankee team lead.

While he would have variously bigger numbers in later years, the complete package of Babe Ruth in 1921 arguably made up the single greatest season of his unparalleled career.

Throughout baseball, the influence of Babe Ruth was beginning to take shape. It wasn’t all Ruth, however; the baseball of 1921 seemed livelier than ever before, leading many to suspect that the ball had been juiced. The manufacturers pled innocence; Thomas Shibe, who oversaw the production of baseballs for use in the majors, went to great pains to convince the public that the ball was no more alive than it had been for years.

Shibe was right. The ball wasn’t juiced; the rules were. A year earlier the spitball and other trick pitches were made illegal; only 17 pitchers, who relied exclusively on the outlaw pitch for their paychecks, were now allowed to throw such pitches for the duration of their careers.

One other factor that led to the sudden jackrabbit brand of high-octane offense was the death of Ray Chapman. Many believed Chapman never saw the Carl Mays pitch that killed him in 1920; the ball had been in continuous use and had been dirtied and roughed up to the point that it was hard to pick out of the background. That in mind, umpires were told to replace the ball more often during the game. It meant a fresher, whiter, and easier-to-see ball always in play, which led to better contact by the hitters with more power, more home runs, more scoring—and more profits to the owners from more fans, who preferred the 11-10 score over that of 1-0.

The upswing in offense was obvious. The National League batting average catapulted 30 points to .289; the American League jumped 10 to .292. As a team, the Detroit Tigers hit .316—an AL record which still stands; four other teams in the majors hit over .300.

Home runs increased with greater speed. Swinging from the heels like Babe Ruth magnetized a good number of other players to try it, and as a result home run production increased in the majors to 937 in 1921, up 300 from the year before. It would only climb from there.

BTW: There were 23 major leaguers who hit 10 or more homers in 1921, way up from the average three or four who surpassed double figures during a typical deadball era season.

Ruth’s influence certainly rubbed off on his teammates. The rest of the Yankee squad hit 75 home runs—enough to finish second in the AL without Ruth. Right-handed hitting Yankee Bob Meusel, given a full-time job at left field, finished second behind Ruth with 24 homers and was third in the AL with 135 RBIs.

While the Yankee offense continually grabbed headlines, the team’s pitching became its secret weapon, quietly leading the AL with a 3.82 earned run average. Carl Mays, not blinking a year after his fatal beaning of Chapman, led the league with 27 wins while losing just nine. Waite Hoyt, a 21-year-old right-hander purchased, like most Yankee teammates, from the Boston Red Sox, surprised everyone by winning 19; veteran Bob Shawkey, a refugee of Connie Mack’s fire sale from the mid-1910s, added 18 more.

The addition of Hoyt, added with the continued improvement of Ruth and Meusel, made it too tough for the Yankees not to win the AL pennant, after finishing a close third the year before. The Cleveland Indians, the defending world champions, didn’t suffer any letdowns in 1921; they simply lacked the monster potential of the Yankees.

Playing the incumbents as best they could, the Indians’ only serious lapse over the previous year was pitcher Jim Bagby, who after winning 31 games in 1920 slipped to a 14-12 mark with a poor 4.69 ERA. But the hitting remained sharp, aided by a bench that batted just under .350.

Ruth and Ruthless

In a towering decade, Babe Ruth mass-produced so many home runs that he managed to fall into the middle of the pack when comparing his totals to those of whole teams during the 1920s.

Cleveland and New York staged a tight AL race throughout the 1921 season, capped by a critical four-game series at the Polo Grounds late in September that would decide the pennant.

Tied for first as the series began, the Yankees and Indians split the first two games—and then the Yankee offense nailed the pedal to the metal. New York sprinted to a 15-0 lead after four innings of the third game, on its way to a 21-7 rout—its biggest offensive explosion of the year, and one of 24 games during 1921 in which the Yankees reached double-digits in runs. In the fourth game it was Ruth, smashing two gargantuan home runs to give New York an 8-7 win and a two-game lead that the Tribe could not overcome in the season’s remaining week.

With the Yankees finally in the World Series for the first time in franchise history, they realized that any travel arrangements weren’t going to be necessary. Their opponents: The co-tenants of the Polo Grounds, the New York Giants.

The Giants had to scramble to make their sixth Series appearance. As late as August, it was the Pittsburgh Pirates who were sitting pretty atop the NL, leading the Giants by seven games thanks mostly to a top-line pitching staff. But the Giants had something most NL clubs—the Pirates included—did not: Money. Manager John McGraw had built up much of the Giants with outright purchases of quality players; his top four starting pitchers (Art Nehf, Fred Toney, Jesse Barnes and Phil Douglas), who made up a steady, sure and solid rotation in 1921, had all been obtained as mid-season acquisitions from ballclubs that had more concern for the bottom line than the bottom of the NL standings.

Desperately trying to catch the Pirates, McGraw made two more midseason deals with the impoverished Phillies. In one trade he got outfielder Irish Meusel, the brother of Yankee outfielder Bob Meusel who was suspended by the Phillies for “lackadaisical play,” never mind that he hit .353 for them. In another deal, the Giants received colorful utility player Casey Stengel, who was so happy to leave Philadelphia that he sped out to New York before McGraw “changed his mind.”

With all the players McGraw felt he needed now in place, the Giants and Pirates met in a crucial five-game series in late August; the Giants won all five. The momentum was so thunderous, it sucked all the life out of the suddenly dispirited Bucs. Pittsburgh’s response was to publicly complain about how the Giants were trying to buy their way to the pennant.

BTW: Starting with the Giants’ five-game sweep, the Pirates went 14-23 down the stretch—while the Giants were 23-9.

The Giants would eventually win 10 straight against the Pirates, finishing the year 16-6 in head-to-head combat against them; they won the NL pennant by four games.

Rich or poor, McGraw still knew how to retool his team with a new wave of young and very talented players without missing a beat in the standings. Infielder Frankie Frisch, 22, became the latest sensation at the plate for the Giants by hitting .341, scoring and knocking in 100 runs each while leading the NL with 49 steals. First baseman George Kelly, nicknamed High Pockets for his lanky 6’4” frame, led the NL in home runs with 23 at age 25. And a graceful young outfielder named Ross Youngs made it look easy with his fourth .300-plus season in four years as an everyday player.

New York City was alive with anticipation for the metropolis’ first “Subway Series,” built up basically as a showdown between Babe Ruth and the Giants. But Yankee pitching set an early tone to suggest that Ruth wouldn’t be needed; Carl Mays and Waite Hoyt tossed shutouts in the first two games. Only two Giants, Frankie Frisch and Johnny Rawlings, were able to collect hits in either contest. The rest of the team was 0-for-46.

The Yankees briefly appeared to be on their way to victory in Game Three with an early 4-0 lead, but the Giants quickly tied it and, later in the seventh, finally slammed through Yankee pitching with eight runs to finish on the upper end of a 13-5 drubbing.

As the Giants turned the tide of momentum, the Yankees needed Ruth more than ever. But the Babe was hurting. A deep bruise suffered in a stolen base attempt during Game Two became infected, and his status—to say nothing of his effectiveness—had become limited. He did manage a home run in Game Four—a ninth inning solo blast that did little to stop a 4-2 Giants victory—but he became so handicapped by Game Five, he scored the eventual game-winning run after bunting his way on base. Afterward, Ruth collapsed in the dugout; he would not be seen on the field until the end of the Series.

Without Ruth, the Yankees wilted. They were outmuscled by the Giants in Game Six, 8-5, and Giants pitchers Phil Douglas and Art Nehf combined to limit the Yankees to a run over the final two games. Ruth made one last stab at it in the ninth inning of the final game, but he grounded out in a pinch-hitting role. John McGraw then watched as another personal thorn in his side, Home Run Baker—who had terrorized the Giants in Series play a decade earlier—grounded sharply into a double play that ended the Series’ last best-of-nine tourney and gave the Giants their first world championship in 16 years.

McGraw showed the Yankees that the Polo Grounds’ landlord ruled over the tenant, both in terms of ownership and performance.

The eviction notice wasn’t far behind.

Forward to 1922: Yankees Go Home Jealous New York Giant manager John McGraw hands an eviction notice to the suddenly popular New York Yankees.

Forward to 1922: Yankees Go Home Jealous New York Giant manager John McGraw hands an eviction notice to the suddenly popular New York Yankees.

Back to 1920: Saviors of the Game Babe Ruth and Kenesaw Mountain Landis restore excitement and credibility to an ailing game.

Back to 1920: Saviors of the Game Babe Ruth and Kenesaw Mountain Landis restore excitement and credibility to an ailing game.

1921 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1921 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1921 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1921 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.