THE YEARLY READER

1927: The Yankee Juggernaut

The first wave of domination by the New York Yankees peaks with the success of the 1927 squad—hailed by many as the greatest baseball team ever assembled.

The 1927 Yankees seem to be the default starting point for any conversation regarding baseball’s best-ever teams, but not without intense discussion. Serious debaters would point to the Pittsburgh Pirates of 1903 or 1909, both with higher winning percentages. Or Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine of 1975-76. Or the colorful New York Mets of 1986. Tougher arguments could be made for the 1906 Chicago Cubs (116-36) or the 1954 Cleveland Indians (111-43)—both of whom had superior records, yet lost in the World Series.

Fans of the Bronx Bombers will even debate whether the 1927 edition is the best Yankees team ever. They often point to the powerful 1961 club led by Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle, the multi-talented 1998 squad, or the collective Yankee dominance of the late 1930s.

Most experts didn’t even believe the Yankees were the best team in the American League when the 1927 season opened for business. A good majority of them put their money behind the Philadelphia Athletics—a team patiently rebuilt by Connie Mack and which featured seven future Hall of Famers.

The Yankees served notice on Opening Day that the soothsayers hadn’t shaken the crystal ball clearly enough. The favored A’s came to Yankee Stadium and, four contests later, limped out with three losses and a discounted 9-9 tie. Hopes for a rebuttal in Philadelphia one month later became hopeless; the A’s lost four of five more to the Yankees, including a doubleheader spanking by scores of 10-3 and 18-5.

BTW: For the year, the Yankees won 14 of 22 games against the Athletics.

With their initial display of power, the Yankees put a stranglehold on first place from day one and never let go. A few other teams hung on for dear life early on, but they would all be choking in the dust left by one the game’s most omnipotent rosters.

Kicking into high gear by June, the Yankees rendered the AL pennant race—such as it was—to a fastidious demise. After a July 4 doubleheader demolition of the second-place Washington Senators—who had come into the twinbill having won 10 games in a row—by scores of 11-1 and 21-1, white flags appeared almost in unison at the other seven AL ballparks.

The lack of suspense in the pennant chase segued into a more intriguing story taking shape within the Yankees lineup. Babe Ruth was having one of those years and then some, challenging his major league record of 59 home runs. But as the season wound its way into August, someone else was on an even more prodigious pace: Lou Gehrig.

Still only 24 years of age, Gehrig was nevertheless prowling at the plate in Ruth’s wake, providing as much—if not more—damage. By early August it was Gehrig, not Ruth, at the top of the home run leaderboard with 38. After averaging a relatively scant 18 homers in each of his first two full seasons as an everyday Yankee, Gehrig’s sudden outburst in 1927 had opposing pitchers praying that it was all just a power-surging blip that would soon cool to normal. But with each passing day, it became frighteningly clear to them that Gehrig’s increased output was going to be the rule, not the exception, for now and the future.

The second coming of Babe Ruth had arrived, and he was batting cleanup right behind him. But Lou Gehrig was, in many ways, the complete antithesis to Ruth. His broad-shouldered, muscular frame was far more ideal in appearance compared to the rounded, thin-kneed Ruth. In terms of character, Gehrig’s quiet, humbling demeanor was a polar opposite to the Babe’s arrogant swagger.

Gehrig would relinquish the home run lead to Ruth, but not so much because he had cooled. Instead, Ruth got hot—very hot. The Sultan of Swat steamrolled through September on a furious mad dash to break his record. By the middle of the month, Ruth quickly reached 50 home runs for the third time in his career—a plateau no one else had yet to reach even once. He continued to climb the ladder, and with four games left to the regular season, he was at 56—three blasts short of his 1921 record.

BTW: Ruth would hit 17 home runs in September, establishing a big-league mark for one month that would be broken by Rudy York in 1937.

Extra Base Strength

Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig weren’t considered baseball’s most famous slugging duo for nothing. In 1927, they crushed a combined 214 extra base hits, setting the pace for other power-packed tandems in the years to follow.

Ruth upgraded his prognosis from possible to probable in a hurry. He hit his first grand slam of the year—off the Athletics’ Lefty Grove—then hit two in his next game against the Senators to tie the mark with two to play. Not waiting for the season finale, Ruth launched fabled number 60 off Washington left-hander Tom Zachary into the right-field bleachers at Yankee Stadium. His teammates drummed their support by banging their bats on the dugout floor; when Ruth returned to the outfield after the inning, he responded to the fans’ wild showering of adoration by giving them a military-style salute.

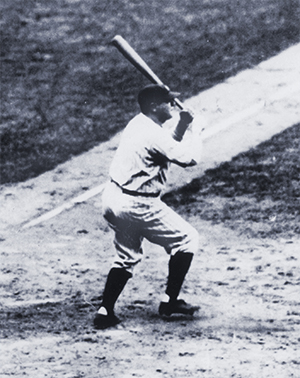

Babe Ruth launches his 60th home run of the season on September 30 at Yankee Stadium, breaking the single-season record he himself set six years earlier; it would stand for 34 years, and would only be broken because of an expanded regular season schedule. (The Rucker Archive)

Ruth displayed his usual lack of humility when reflecting on his new milestone. “Sixty, count ’em, sixty,” he quipped, “Let’s see some son-of-a-bitch match that.”

There was little the 1927 Yankees did wrong. Their 110-44 record placed them a full 19 games ahead of the second-place A’s. They scored more runs, collected more hits and homers and walked more. The stat sheet exposed only one run-of-the-mill aspect to the Yankees’ powerful offense: Stolen bases. Baseball’s Atlas shrugged at the alleged weakness; steals were a needless necessity as pinstriped runners reached base and simply waited for Ruth and Gehrig to give them a free ride home via a blast over the fence.

Ruth’s 60 home runs were punctuated by a .356 batting average, 164 runs batted in and 158 runs scored. Gehrig, although finishing second to Ruth with 47 homers, batted higher (.373) and knocked in more runs (175); he also topped the league in doubles (52) and tied for second in triples with 18. Between them, Ruth and Gehrig accounted for a quarter of the league’s total home run output in 1927.

There was far more to the Yankees than just Ruth and Gehrig. Leadoff hitter Earle Combs matched Ruth’s .356 batting average and scored 137 runs, while Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri knocked in 100 runs each. The team maintained a slugging percentage of .489 that set a major league record, and was surpassed in 1927 by only five players outside of New York in the AL.

BTW: The 2003 Boston Red Sox would eclipse the 1927 Yankees’ team slugging percentage mark.

The New York pitching didn’t grab as much attention but was no less effective; their league-leading 3.20 earned run average was easily the AL’s best. Proven hurlers Waite Hoyt (22-7), Herb Pennock (19-8), Urban Shocker (18-6) and Dutch Ruether (13-6) were joined by the staff’s big surprise, 30-year-old rookie Wilcy Moore. Used mostly as a reliever, Moore won 19, saved 13 and led all individual pitchers in the AL with a 2.28 ERA; Hoyt and Shocker placed second and third.

The Yankees coasted into the World Series with the swagger of a chest-thumping champion among amateurs, demanding: “Who’s next?”

The Pittsburgh Pirates remained a talented yet deeply troubled team since their last World Series appearance two years earlier. An intense and highly publicized player revolt in 1926 against Pirates manager Bill McKechnie, led by veteran basestealing guru Max Carey, resulted in the departure of Carey and two other long-time Pittsburgh stalwarts, Babe Adams and Carson Bigbee; McKechnie, too, would soon be gone as the team’s performance went through freefall in the controversy’s aftermath.

BTW: Adams, Bigbee and Carey protested the presence of former Pirates manager and current bench coach Fred Clarke, who they labeled as owner Barney Dreyfuss’ shifty eyes and ears in the dugout.

McKechnie’s replacement, former Detroit shortstop Donie Bush, turned up the intensity in the clubhouse during 1927 with another contentious issue. Bush strongly felt that Kiki Cuyler, the team’s breakout star of 1925, had developed into an underachiever by not giving it his all. In a blunt show of discipline by the new manager, Cuyler was shown the bench by August—where he would stay for the rest of the season, despite having batted .313 to that point.

At that moment, the Pirates trailed only the Chicago Cubs in the National League standings; but this time the Bucs would contentedly play the witness to someone else’s late season collapse, as the Cubs played awful baseball through the rest of the year—losing 27 of their final 42 games—and eventually wrapped it up in fourth place. The Pirates grabbed the top spot, and consistently managed to keep the favored New York Giants and defending champion St. Louis Cardinals at arm’s length to capture the NL flag.

Pittsburgh’s run for the top was fueled by rookie outfielder Lloyd Waner, who batted .355 with a league-leading 133 runs. His 223 hits were surpassed by just one other player in the NL: His brother. Having made his own splash a year earlier as a first-year Pirate, Paul Waner’s sophomore campaign included league highs in batting average (.380) and RBIs (131). Well under six feet and weighing 150 pounds each, the Oklahoma-bred Waner brothers didn’t look intimidating, yet became major contributors to an offense that paced the NL in hitting at .305.

BTW: The Pirates’ team batting average, minus the Waners’ numbers, was .284.

Babe Ruth was shown a picture of the Waner brothers as the World Series neared and looked perplexed. “Why, they’re just kids,” he said, “if I was that little, I’d be afraid of getting hurt.”

The Yankees took batting practice at Forbes Field the day before Game One, and Pittsburgh players who surfaced in the dugout were reportedly awestruck by the massive power display being put on by Ruth, Gehrig, et al. When pitcher Herb Pennock was nailed just above the kneecap by a sizzling batting practice drive, the Pirates onlookers were more consumed with the thought of having to field against that hitting rather than the possibility of not having to face a great thrower in Pennock.

Simply put, the Yankees were too awesome to buckle under to the Bucs, sweeping them in four games. Yet, the blanking of the Pirates wasn’t as prohibitive as led to believe; Game Three, an 8-1 New York win behind the revived Pennock’s three-hitter, furnished the Series with its lone one-sided affair. But the Yankees were in control throughout, staying on top of and winning close contests in Games One and Two. The only semblance of suspense came in Game Four, won by the Yankees in the bottom of the ninth when a wild pitch sent Earle Combs home with the Series-ending run.

The World Series was as predictable as could be. Babe Ruth routed two home runs, the only two hit in the Series; Gehrig provided four extra base hits and played sharp, despite a serious illness to his mother that threatened his attendance at the Series; and the underrated, stingy Yankees pitching had an overall 2.00 ERA and allowed just four walks in 36 innings.

Try as they might, the Pirates went home convinced they had just been beaten up by one of the greatest. The Waners—“Big Poison” Paul and “Little Poison” Lloyd—managed to sparkle, hitting a combined .367; but the rest of the Pittsburgh side disappointed with a .180 average. The benched Kiki Cuyler, a future Hall of Famer, never came to bat. And Pittsburgh’s four superb starters—Ray Kremer, Lee Meadows, Vic Aldridge, and brief wonder Carmen Hill, winner of 22 games—gave it their best shot, but could not successfully corral the Yankees lineup now known as “Murderer’s Row.”

The best team ever? The debate continues.

Not to be forgotten, however, are the pointed arguments exhaled from the dropped jaws of Pirates players who came to watch the 1927 New York Yankees take batting practice.

Forward to 1928: A Ruthian Rout World Series underdogs, a beat-up New York Yankee squad comes alive behind Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Forward to 1928: A Ruthian Rout World Series underdogs, a beat-up New York Yankee squad comes alive behind Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Back to 1926: One Hell of a Hangover Old pro Pete Alexander comes in cold—and sober, maybe—to famously rescue the St. Louis Cardinals from the New York Yankees at the World Series.

Back to 1926: One Hell of a Hangover Old pro Pete Alexander comes in cold—and sober, maybe—to famously rescue the St. Louis Cardinals from the New York Yankees at the World Series.

1927 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1927 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1927 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1927 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.