THE YEARLY READER

1928: A Ruthian Rout

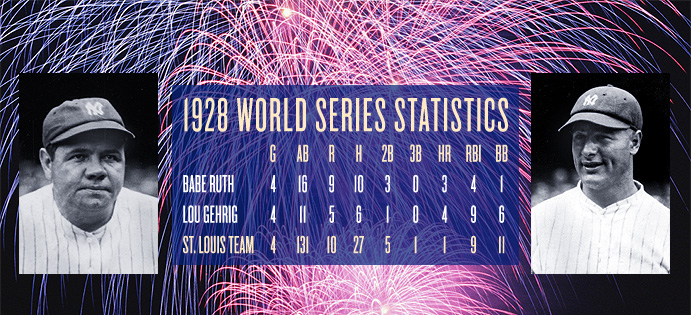

Surviving a tough pennant race with the Philadelphia A’s, the New York Yankees set out to gain revenge for their 1926 World Series loss against the St. Louis Cardinals—with Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig ready to provide an impressive display of offensive fireworks.

Babe Ruth was nursing a bad ankle. Lou Gehrig’s lip was swollen after being knocked senseless by a sharply hit ground ball. Tony Lazzeri’s arm was extremely sore, Earle Combs’ wrist badly bruised, and pitchers Herb Pennock and Wilcy Moore were both done for the year.

The New York Yankees literally limped into their third straight World Series, lacking that fiery breath of invincibility they exhaled when they blew away all challengers the year before.

In their path for this year’s Series were the St. Louis Cardinals, who upset the Yankees two years earlier—and now were alternately confident and salivating to take advantage of the battered and bruised New Yorkers.

Four massive doses of an apparently cured Ruth and Gehrig later, and about the only thing resembling a medical ward would be the Cardinals’ pitching staff.

That the Yankees rose to the occasion in repeating as World Series champs may not have been their biggest test of the year.

After their legendary 1927 campaign, the Yankees were undoubtedly selected to repeat in 1928. Their only major offseason loss was pitcher Urban Shocker, who retired, came out of retirement, then quit again as he battled contract disputes and, more sadly, a growing heart illness that would take his life before the year was over. A few new players had come aboard, including a cocky 22-year-old infielder named Leo Durocher, who quickly made a habit of needling Babe Ruth the wrong way.

On the field, the Yankees picked up where they left off the year before; they won 34 of 39 games in one stretch, and by July 1 had slammed their way out to a 13.5-game lead in the American League standings. As always, Babe Ruth led the charge, on the potential brink of yet another record-breaking crusade; by late June, he had already hit 30 home runs, well on pace to break the mark of 60 he set a year earlier.

But a funny thing happened on the way to another pennant: The Yankees became mortal. Injuries occurred. Players slumped. New York suddenly found itself playing little better than .500 ball, and the door was open for the contenders. And in came the Philadelphia Athletics.

Life as an A’s fan had been depressing in the years following manager Connie Mack’s cost-driven breakup of his virtual 1910-14 dynasty. The A’s instantly went from champs to doormats and stayed there for almost a decade, with Mack seemingly more focused on surviving than winning.

By the early 1920s, Mack had replenished his bank account enough to dust off the checkbook and begin a prolonged shopping spree to steadily build up a new reign of power.

Mack paid $40,000 for Aloysius Szymanski, a.k.a., Al Simmons, a.k.a, Bucketfoot Al, for a bizarre method of swinging where his front feet backed out of the box instead of towards the front of it, nevertheless making him a dangerous hitter. Another $40,000 went for Max Bishop, a solid second baseman with a fair bat but an excellent eye that helped him garner a mountain of walks. For $50,000 more, Mack bought Mickey Cochrane, a fearless catcher who possessed a sharp batting stroke. And in 1925, Mack forked out an eye-opening $100,000 for pitcher Lefty Grove, a testy, highly sought prospect who was in no hurry to leave the International League’s Baltimore Orioles—perhaps the most prestigious minor league ballclub of all time—because he was making a decent living there.

BTW: The $100,000 purchase of Grove was the most expensive for a minor leaguer to date.

Whatever loose change Mack had left was all he needed to steal away a 17-year-old kid named Jimmie Foxx, whose husky frame was so intimidating, it was later commented that he wasn’t scouted—he was trapped.

To season his stable of blue-chip talent, Mack brought in a parade of legends at the tail end of their careers to give the youngsters extra leadership in the clubhouse. Fortysomethings Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Zack Wheat and Tris Speaker all imparted whatever wisdom the kids needed, hoping in return to be rewarded with one last championship—or in the case of Cobb and Wheat, their first ever—before retiring from the game.

The Athletics’ rebound to the top of the AL was as steady and sure as Mack had envisioned. Escaping the cellar in 1922, the A’s continually gained a notch in the standings before igniting to a second-place finish in 1925. After ending up just six back of the Yankees in 1926, they improved by eight games the following year—but finished miles behind the great Yankee team of 1927.

Running Hot and Cold

In over 50 years of managing, Connie Mack seldom represented the median; his teams were either stunningly good or awfully bad. This is no better exemplified than his results from his two dynasties in Philadelphia—separated by an extended trip through the AL basement.

As the Yankees idled through the summer of 1928, the A’s embarked on a timely rampage and gradually closed in on New York’s once insurmountable lead. By September 7, the gap was entirely erased when the A’s swept a doubleheader from the Boston Red Sox, while the Yankees were being humiliated twice by the Washington Senators during a home twinbill. New York rebounded the next day with a victory, yet dropped a half-game into second place; the A’s had taken two more that day from the cellar-dwelling Red Sox.

The schedule makers grinned; a four-game showdown between the Yankees and A’s was next.

A record gathering of 85,264 jammed their way into Yankee Stadium—a reported 100,000 were turned away—for the first two games of the series, a doubleheader that would likely determine the two contenders’ momentum for the balance of the season.

New York starter George Pipgras, enjoying a career year in the Bronx, blanked the A’s in the first game, 5-0, scattering nine hits and two walks in the process. In the nightcap, Philadelphia led 3-1 in the seventh inning and looked poised for a split on the day when the roof caved in. The Yankees scored two in the seventh to tie and, an inning later—with two outs and the bases loaded—Yankee outfielder Bob Meusel hammered a 3-2 pitch off knuckleballer Ed Rommel for a grand slam that sealed both the game and the doubleheader sweep.

The teams split the last two games of the series, but the psychological damage upon the A’s was all but complete. Philadelphia may have mastered the other six AL teams, but their complete inability to overcome the titanic Yankees—against whom the A’s would lose 16 of 22 games in 1928—built a mental roadblock to any confidence that Philadelphia could pass them up in the standings. Sure enough, New York never lost control in the season’s final three weeks and headed to its third straight World Series; the A’s finished 2.5 games back.

Although the Yankees continued to furnish a plethora of talent, it was Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig who once again paired up for the real destruction. Ruth fell off his record home run pace but still ended the year with 54; Gehrig was a distant second with 27, but matched Ruth with 142 runs batted in while finishing third in the AL with a .374 batting average.

The return of the St. Louis Cardinals to the National League’s pinnacle was born out of managerial strife of years past. When owner Sam Breadon jettisoned player-manager Rogers Hornsby following the Cardinals’ 1926 World Series triumph after a series of confrontations between the two—often in front of the other players—catcher Bob O’Farrell was given the pilot seat for 1927. O’Farrell gave them a better record—but placed second to Pittsburgh. To Breadon, it was a drop-off all the same, and O’Farrell was demoted at year’s end—replaced by Bill McKechnie, who when last seen as manager in 1925 was weathering stormy internal battles of his own in Pittsburgh, leading to his dismissal there.

Trailing early in the NL standings behind Cincinnati, the Cardinals pulled ahead by June and stayed there, though the competition was brisk. The New York Giants, with yet more new young faces in slugger Mel Ott and screwball pitcher Carl Hubbell, gave closest chase to St. Louis, but finished two games back. Close on the Giants’ heels were the Chicago Cubs, who featured miniature yet powerful slugger Hack Wilson and a rediscovered Kiki Cuyler. Defending NL champion Pittsburgh, despite a franchise-record .309 team batting average, was beset by an inconsistent pitching rotation and fell to fourth.

BTW: That the Giants stayed as close as they did was impressive, given that they lost their best hitter (Rogers Hornsby) and pitcher (Burleigh Grimes) from the year before, and lost manager John McGraw for six weeks after a taxi struck him and broke his leg.

The Cardinals were potently well balanced. First baseman Jim Bottomley, an amiable man by nature, had his .325 batting average compounded by NL highs in triples (20), home runs (31) and RBIs (136); he deservedly won league MVP honors. Outfielder Chick Hafey, playing his first full season, may have gotten the rest of the votes, batting .337 with 27 homers and 111 RBIs.

20-20-20 Vision

The Cardinals’ Jim Bottomley became only the second in a very short list of major leaguers who clubbed out at least 20 doubles, triples and home runs each in one season.

An early-season trade also shifted fortunes in St. Louis’ favor. No longer managing and off to an awful start on the field, Bob O’Farrell was dealt to New York for 36-year-old outfielder George Harper, who himself appeared to be struggling towards an early retirement. The deal did wonders for the Cardinals, zilch for the Giants. O’Farrell never found his groove and batted .195 at New York, while Harper revived himself at St. Louis by hitting .305 with 17 home runs—including three blasts in a crucial late-season victory over his former mates at the Polo Grounds.

BTW: There was a silver lining to the trade for the Giants; Harper’s departure opened up an everyday spot in the outfield for future Hall of Famer Mel Ott.

The experts had the Cardinals ready to pounce on an injury-riddled Yankees team in the World Series, but St. Louis was instead victimized by one of the most brutal exhibitions of one-two sluggery in Series annals.

Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig wasted no time. They hit back-to-back doubles in the first inning of Game One, setting the tone for a 4-1 triumph. In Game Two, Gehrig hit a first-inning, three-run blast off 1926 Series hero Pete Alexander who, sober or not, was ripped from the mound by the third inning. In Game Three, it was Gehrig smashing two more home runs off Jesse Haines in a 7-3 Yankees victory.

Facing a sweep, St. Louis starter Bill Sherdel—a 21-game winner during the regular season—went to desperate measures in Game Four. Ahead 2-1 in the seventh, Sherdel faced Ruth—who hit a solo home run off him earlier—and fired a quick pitch for a strike, hoping to catch Ruth off guard. The umpire, noting that such pitches were illegal, declared it a non-pitch; Sherdel and the Cardinals bench exploded while Ruth patiently stood by with a wide grin. Once the argument abated, Ruth answered the hasty tactics by homering once more off Sherdel.

BTW: Quick pitches, allowed in the American League but not the National League, were outlawed for the World Series.

For good measure, Gehrig, the next batter, also connected.

The cherry on top was still to come. Ruth, now facing Alexander (in relief of Sherdel) in the eighth, homered for the third time in the game, the second time he had gone deep thrice in a contest—both in World Series competition, both times against the Cardinals.

Having swept the World Series for the second straight year, the Yankees’ clobbering of the Cardinals was done with more authority. Between them, Ruth and Gehrig would hit a whopping .593 (16-for-27) with seven home runs. (Ruth and Gehrig’s World Series slugging percentage: 1.519.) They also scored 14 runs and knocked in 13. It overcame the paucity of the other New York hitters, who collectively batted just .187.

Once again, the New York Yankees perched themselves at the top of the baseball world. And because their aches and pains had caused the pundits to write them off in advance, this triumph felt all the more sweet.

It would be as good as it got for the first wave of Yankee domination.

Forward to 1929: Running on Ehmke All but washed up, veteran pitcher Howard Ehmke gets the dream call for Game One of the World Series and delivers, setting the tone for a long-overdue championship for the Philadelphia A’s.

Forward to 1929: Running on Ehmke All but washed up, veteran pitcher Howard Ehmke gets the dream call for Game One of the World Series and delivers, setting the tone for a long-overdue championship for the Philadelphia A’s.

Back to 1927: The Yankee Juggernaut The 1927 New York Yankees—the team often considered as the greatest ever—sweeps away the competition.

Back to 1927: The Yankee Juggernaut The 1927 New York Yankees—the team often considered as the greatest ever—sweeps away the competition.

1928 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1928 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1928 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1928 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.