THE YEARLY READER

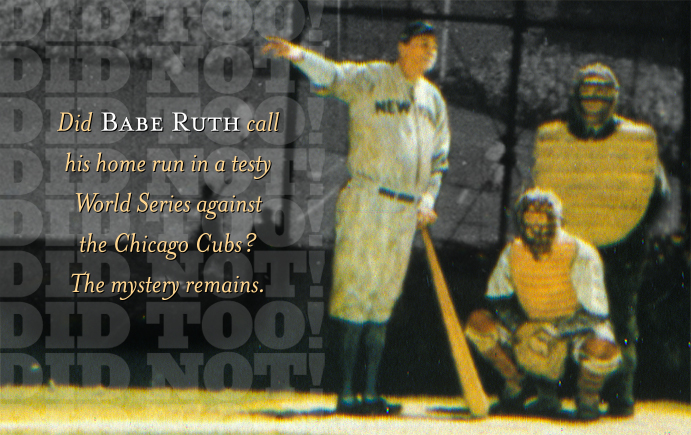

1932: The So-Called Shot

The mystery and controversy revolving around a “called” home run by Babe Ruth enlivens a World Series matchup with the Chicago Cubs, already made acrimonious by the appearance of current New York Yankees—and former Cubs—manager Joe McCarthy.

(The Rucker Archive)

Babe Ruth had an uncanny ability to do as he pleased on a baseball field. Even when the competition stepped it up and tried everything under the sun to stop him, he found little difficulty in brushing it aside.

Few of his home runs were wasted. They were well placed and well timed for the occasion. Three homers in a World Series game, done twice. The first homer ever hit at Yankee Stadium. The first homer in All-Star Game history. Three homers in one of his very last games, as though departing baseball in a scripted blaze of glory.

But some believed—and still do—that Ruth’s justified arrogance reached its ne plus ultra in Game Three of the 1932 World Series when the Babe appeared to point towards the center-field bleachers at Chicago’s Wrigley Field to let everyone know where he was going to hit the next pitch—and proceeded to deposit a straight-away smash precisely to that spot, as advertised.

“The Called Shot” has become one of sport’s great legends, and a controversial one at that. There’s no argument that Ruth pointed his finger upward and toward Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, standing on the mound ready to throw; the debate is over what Ruth meant with the gesture.

Whatever the motive, the Babe’s theatrics arose out of a plethora of acrimony that had developed between the Yankees and Cubs going into the World Series. The genesis of that tension was former Cubs—and current Yankees—manager Joe McCarthy.

The no-nonsense skipper methodically built the Cubs into a World Series participant by 1929, but when the Cubs appeared on the verge of elimination a year later, McCarthy quit right before season’s end when word leaked he was going to be fired by disappointed Cubs owner William Wrigley.

When Wrigley followed through with his plan, he told the press: “I have always wanted a world championship team, and I am not sure that Joe McCarthy is the man to give me that kind of team.”

It was a statement that would haunt the Cubs. Twice over the next five years, Chicago would reach the World Series looking for that championship sans McCarthy. Both times, the Yankees would get in the way.

The man leading the Yankees from the dugout on both occasions: Joe McCarthy.

Following Miller Huggins’ death at the end of 1929, the Yankees promoted pitcher Bob Shawkey as their new manager for 1930, but the team finished third—a shameful result as far as Yankee expectations go. Wasting no time, the Yankees immediately nabbed an available McCarthy from Chicago as their new man. McCarthy advanced New York back to second in 1931, but still fell short of the powerful Philadelphia A’s for the AL flag.

The Yankees’ problem in catching the A’s was simple: The pitching staff was almost a full run worse than the great Philadelphia rotation led by Lefty Grove. McCarthy worked on addressing this obstacle and discovered patience to be the rule. He looked at the promising young Yankees arms and crossed his fingers that they might blossom faster than expected.

In 1932, McCarthy got a double dose of luck. Not only did the pitching improve in New York, it declined in Philadelphia. Lefty Grove was his usual superhuman self, but the rest of the A’s staff floundered, its earned run average dropping to fifth in the American League. The hitting remained equally powerful on both sides, but with Yankee pitching a sudden and more superior commodity, it brought New York back to the top of the AL, a spot for which the A’s had shut the Yankees out of for three years.

Anchoring the Yankees rotation was 23-year-old Lefty Gomez, a man whose brand of humor seemed more suited for Vaudeville, but was all business on the mound—winning 24 games in his second full season. Red Ruffing, yet another castoff from the downtrodden Boston Red Sox, loved his newfound offensive support and it energized his game, finishing with the AL’s second best ERA at 3.09—trailing only Lefty Grove. And rookie Johnny Allen won 17—while losing just four—as part of the five-man rotation.

At the plate, the Yankees presented one of their most diversely talented lineups ever. Babe Ruth hit over 40 home runs for the seventh year in a row. Four different players knocked in 100 runs, while four scored 100. Third-year outfielder Ben Chapman led the AL with 38 steals. Veteran third baseman Joe Sewell struck out just three times over 500 at-bats—the lowest strikeout frequency by a full-time player in major league history.

The Yankees’ 107 wins included a then-record 62 at home; they were never shut out. They didn’t miss a beat even with the month-long suspension of gifted young catcher Bill Dickey, who was batting .360 when he broke the jaw of Washington’s Carl Reynolds during a mid-season altercation at home plate.

BTW: After a collision between the two, Reynolds got up and re-approached home plate to tag it—but was tagged in the jaw instead by Dickey, who thought Reynolds was coming after him.

With McCarthy jettisoned from Chicago, the Cubs relied on Rogers Hornsby to deliver the world title the late William Wrigley was searching for. Hornsby had previously won a World Series managing St. Louis in 1926, using the everyday benefit of his tremendous hitting talent to get them there. That was then, this was now: An ankle injury sidelined the Rajah to a full-time bench manager, the role his Cubs players appreciated him less for, and tensions rose. Like McCarthy, Hornsby was a colorless disciplinarian, but he was less adept at pushing the right buttons. Hornsby’s stern, distant rule kept the Cubs in the National League pennant race, but with a record barely above the .500 mark. If that wasn’t enough of a concern, the Cubs soon learned that Hornsby, a frequent patron at the track, had apparently lost his good luck—and was hitting up players for money to get it back. By the beginning of August, Hornsby was dismissed.

BTW: William Wrigley died in January; Cubs ownership was passed on to his son Philip, who was said to be far less interested in baseball than his father.

Exit the Rajah, enter Jolly Cholly. Now in his seventh year as Chicago’s first baseman, Charlie Grimm was given the managerial reins. To the players’ total relief, the good-natured Grimm was the polar opposite of Hornsby, playing his banjo in the clubhouse and keeping the team’s spirit high, in contrast to the tense, morgue-like atmosphere Hornsby had created. Like schoolkids released from boarding school, the Cubs responded by winning 37 of 57 under Grimm—including 18 in one 20-game stretch—and sneaked past the Pittsburgh Pirates to clinch the NL pennant.

Billy Jurges’ midseason injury (thanks to a suicidal girlfriend) only deepened the wounds of anger between the Cubs and Yankees when his replacement, ex-Yankee Mark Koenig, was rewarded a half-share of World Series money despite hitting .353 for Chicago down the stretch. (The Rucker Archive)

Another young promising star in Chicago, shortstop Billy Jurges, had his season curtailed in July when his girlfriend pulled a gun on herself in front of him; in an attempt to save her, he was shot twice. He would recover to return at the end of the season, but in his place, the Cubs picked up Mark Koenig, a former starting member of the 1927 Yankees whose major league career had diminished to a near-end the year before at Detroit. In Jurges’ place, Koenig was short of spectacular; he batted .353 with three home runs in 33 games down the stretch, contributions that may have helped send the Cubs over the top.

With the pennant clinched, the Cubs sat down to vote on shares for the upcoming World Series. Needing a unanimous vote of ayes, two players—including Jurges—said nay to a full share for Koenig. Instead he was given a half-share and six World Series tickets—“one behind every post,” it was said.

BTW: Koenig was luckier than Rogers Hornsby, who received no shares whatsoever from his disgruntled ex-players. Hornsby protested to commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to no avail.

When the Yankees got word of this, they became furious. Koenig had been a popular player in New York, and coupled with the Cubs’ shafting of McCarthy before joining the Yankees, enough fodder had been created to inspire revenge for a team that had never faced the Cubs before. And when the Yankees equipped the press with references to the Cubs as “cheapskates,” “penny-pinchers” and “nickel squeezers,” the blackboard in the Chicago clubhouse had been filled with motivation of its own.

Vicious bench jockeying became the norm when the Series commenced. The Cubs saved their best for Babe Ruth, who had spoken most vociferously about the Koenig affair. Spectators in the stands were horrified by the torrent of profanity raining out of both dugouts.

Between the lines, the Yankees promptly showed whose bats talked loudest as they ripped apart the Cubs in the first two games in New York, sending Cubs starters Guy Bush and Lon Warneke quickly to cover under an endless assault of slugging firepower.

Though down two games, the heckling from the Cubs’ bench only intensified when Ruth came to bat in Game Three at Wrigley Field. All it did was present Ruth with a challenge—a mistake the Cubs were about to pay for.

He had already homered in the first inning when he came back to bat in the fifth. After going ahead in the count at 2-1, Ruth took a second strike from 15-game winner Charlie Root to even the count. He then stood up, looked to the Cubs bench, and then pointed toward the field.

Why he did it—and what he said to accompany it, if anything—depended on who you believed. Lou Gehrig, on deck, swore Ruth was promising a home run on the next pitch; several reporters in the stands agreed. Chicago catcher Gabby Hartnett, however, remembers Ruth telling the Cubs bench, “That’s only two strikes.” Root recalls Ruth saying to him, “You still need one more, kid.”

There was no debate over what happened next. Ruth swung at the next pitch and thundered it over the center-field wall, a blast many believed was the longest yet hit at Wrigley.

As he always seemed to do, Lou Gehrig followed up Ruth’s blast with one of his own, his second of the game.

The Yankees won Game Three, 7-5, and shut the Cubs up for good the next day with a 13-6 thumping in Chicago, aided by a pair of Tony Lazzeri home runs. The dominant four-game sweep of Chicago included a .313 team average and eight home runs. The Cubs pitching staff limped home with a 9.26 team ERA.

Ruth, Gehrig…and Those Other Yankees

From 1927-32, the Yankees participated in three World Series and swept their opponents each time. The team’s 12-0 Fall Classic mark couldn’t possibly have been accomplished without the explosive efforts of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, who annihilated the opposition—while the rest of the Yankee hitters meekly tagged along.

Alas, Ruth’s called shot is probably a sentimental case of myth over fact. Had he truly called his home run, Ruth would have bragged endlessly about it to the press afterward until his voice box gave out. Instead, he was unusually coy in giving his version of events as if caught off guard, and only as the years went by did he occasionally tell people behind the scenes that it never really happened.

But, as Ruth would add, it made for one hell of a story.

Forward to 1933: Making Little Napoleon Proud An ailing John McGraw hands the managerial reins to first baseman Bill Terry—who promptly rides the New York Giants back to triumph.

Forward to 1933: Making Little Napoleon Proud An ailing John McGraw hands the managerial reins to first baseman Bill Terry—who promptly rides the New York Giants back to triumph.

Back to 1931: The Peppering of Philly Aggressive and colorful, Pepper Martin leads the St. Louis Cardinals in ending the Philadelphia A’s two-year rule over baseball.

Back to 1931: The Peppering of Philly Aggressive and colorful, Pepper Martin leads the St. Louis Cardinals in ending the Philadelphia A’s two-year rule over baseball.

1932 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1932 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1932 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1932 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.