THE YEARLY READER

1935: The Babe’s Bittersweet Bow Out

Babe Ruth performs one final year—with the struggling Boston Braves—and watches both his immortality and promise of front office involvement quickly evaporate.

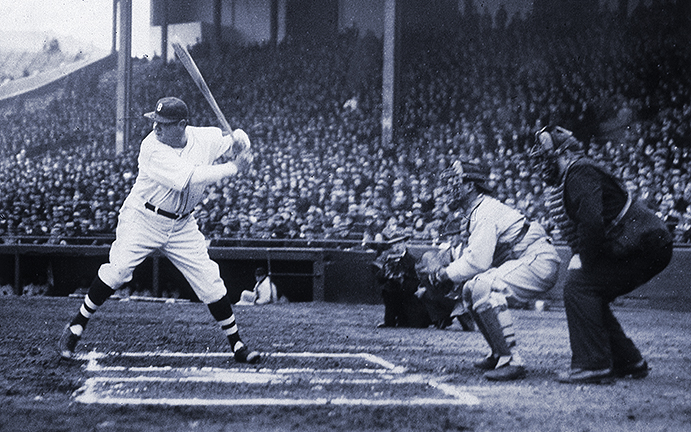

Babe Ruth swings away in his first official game with the Boston Braves. He would belt a home run in the contest against New York Giants ace Carl Hubbell…and his season would go deeply downhill from there. (The Rucker Archive)

At the age of 40, Babe Ruth had accomplished everything he could want as a baseball player. He had a virtual monopoly on the home run section of the record book, was a member of seven World Series champions, won a batting title and was twice won 20 games as a pitcher.

All Ruth wanted to do now was to be a big-league manager.

He would find it to be his toughest challenge.

Throughout a 1934 season that would be his last as a New York Yankee, Ruth made noise—lots of it—regarding his status for 1935. He desperately wanted Joe McCarthy’s job as Yankee manager, felt he earned it, and let the baseball world know about it. His yearlong lobbying caused so much distraction within the Yankees, it may have kept the team from being able to focus on the American League pennant race. This may have been Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert’s justification not to hire Ruth, though he had an even better reason: There was no need to part with McCarthy, currently the game’s best manager.

The best Ruppert was willing to do was accommodate Ruth with the manager’s job at Newark, the Yankees’ top-level minor league affiliate. Stuck below the major league level was hazardous to Ruth’s ego; he said thanks but no thanks.

Teams had knocked on Ruppert’s door before 1934, asking about Ruth’s availability for the upcoming season, but Ruppert wanted him as a player for one more year. When Ruth’s 1934 numbers (a .288 average with just 22 homers and 84 runs batted in) showed him to be an aging icon whose time had come and gone, Ruppert freed the Babe to find his managerial destiny.

In Washington, Senator owner Clark Griffith needed to turn his team around and had a managerial spot available—but not a lot of money, as usual—for Ruth; he backed away when Ruth wanted double the offered cash. In Philadelphia, Connie Mack was contemplating retirement from the A’s and considered Ruth as his replacement, but when he visited Japan with a team of major league stars that included Ruth for a postseason tour, he got cold feet watching the Babe’s disruptive clubhouse persona first-hand; Mack rescinded his thoughts and would manage another 15 years. And in Boston, Tom Yawkey entertained ideas of “bringing back” Ruth to manage the Red Sox, with whom Ruth began his career 21 years earlier. But general manager Eddie Collins, the former hitting star for the A’s and White Sox, convinced Yawkey otherwise.

Across town at Boston Braves headquarters, owner Emil Fuchs was watching a franchise on a steady upswing. A constant denizen of the National League’s lower reaches throughout the 1920s, the Braves underwent annual improvement under the wings of manager Bill McKechnie, who had previously won NL pennants at Pittsburgh and St. Louis. Fuchs contacted Ruth with a tempting proposition: Come play for the Braves, be a part of the front office and eventually get the pilot seat.

It may not have been ideal for Ruth, but teams had stopped calling. Besides, the financial details—a $25,000 salary plus a percentage of the profits—looked sweet.

Ruth didn’t homer during spring training, but the Babe had made an art form of rising to the occasion when it mattered the most. On Opening Day against the Giants at Braves Field, Ruth crushed a 430-foot homer and singled off ace Carl Hubbell for a 4-2 Boston win.

And that’s as good as it got for the Braves and Ruth in 1935.

After belting a second home run five days later, Ruth went hitless over his next 20 at-bats, and with each passing game knew he was performing on borrowed time, a pale shadow of his former greatness. The season wasn’t a month old when he notified the Braves he couldn’t play any more. But a long road swing was coming, and the major league stops along the route had planned special days to honor Ruth. The Braves pleaded with Ruth to hang in there; he reluctantly agreed.

Ruth entered Pittsburgh on May 25 looking beyond repair, having collected just three hits in his previous 44 at-bats. But suddenly, the Ruth of yesteryear emerged for one last great breath of immortality. He ripped three home runs in a 4-for-4 day, with six RBIs, against the Pirates; his third blast cleared the right-field roof at Forbes Field, landing an estimated 600 feet from home plate. The toughest test for the out-of-shape Ruth might have been just circling the bases for the third time on the day.

BTW: Ruth’s shot over the roof was arguably the longest ever hit during Forbes Field’s 61-year history.

It was the 714th, and last, home run of Babe Ruth’s career.

Following his power surge at Pittsburgh, Ruth’s wife Claire desperately tried to talk him into retiring and going out on top in pure Ruthian style, but Ruth wanted to honor his deal and complete the road swing. He did so, though there would be no more magic left in his bat. The Babe announced his retirement on June 2.

The deal to bring Ruth to Boston was catastrophic for all involved. Ruth left the Braves batting a paltry .181, and worse, it became increasingly clear that the promise of Ruth’s front-office involvement with the Braves had been a joke. Named assistant manager and vice president when hired, both positions held only token meanings.

The Braves grew more pitiful without Ruth. They finished at 38-115, the worst record in modern NL history. Who knows how much more pathetic they would have been without slugger Wally Berger, who carried what little was left of the team by leading the NL in home runs (34) and RBIs (130). Ruth finished second on the team in homers—with six.

Carrying the Team on Your Bat

It was nothing new for the Braves’ Wally Berger to produce a massive share of his team’s offense. Only Babe Ruth, Berger’s teammate for a brief time in 1935, would hit a higher percentage of his team’s home runs over a six-year period.

A day after Ruth retired, Emil Fuchs threw in the towel as well, announcing the Braves were up for sale. The new owners would be so determined to erase the bad memories of 1935, they would rename the team the Bees.

BTW: By 1941, all would be forgiven, and “Braves” returned on the uniform for keeps.

Babe Ruth would never manage. An assistant coaching role at Brooklyn in 1938 was as close as he got. He would just have to be content with being remembered as the greatest baseball player of all time.

While one owner bowed out from total disappointment, another in Detroit could taste his first championship after decades of frustration. After reaching, and losing, the World Series over his first two years as boss of the Detroit Tigers in 1908-09, Frank Navin helplessly watched over the next 25 years as his team remained competitively silent—a decent team, yet never a front-runner.

It had become a race of sorts for Navin, whose health problems were of such concern that, five years earlier, doctors had advised him to sell the club and take it easy. A quiet yet stern individual, Navin insisted he wouldn’t relax, that he would “stick around” until his Tigers won it all.

Detroit came close in 1934, returning to the Series but losing again, in seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals. But the Tigers had such a solid balance of youth and experience, it would be a tough chore for anyone to keep them from repeating as AL champs in 1935. Sure enough, no one could.

Navin, who also had considered Babe Ruth to pilot his team, had since chosen catcher Mickey Cochrane, who had absorbed enough leadership and post-season experience from his years catching for the A’s. In his second year at Detroit as player-manager in 1935, he gave the Tigers their second straight pennant.

In outlasting the Yankees by three games, the Tigers were energized by 24-year-old Hank Greenberg, an imposing figure of well over six feet who established himself as a powerful presence in his third full season. Greenberg tied Jimmie Foxx for the AL home run lead with 36, while his 170 RBIs were far ahead of second-place Lou Gehrig, who had 119.

BTW: The Tigers’ final three-game margin over the Yankees wasn’t as close as it sounded; Detroit led by eight games going into the season’s final week, before safely slumping.

The Detroit roster was also bolstered by Charlie Gehringer (a .330 batting average, 19 home runs and 108 RBIs), who was so consistent to be devoid of slumps, he was nicknamed the Mechanical Man; a solid four-man rotation led by Tommy Bridges (21-10) and 25-year-old Schoolboy Rowe (19-13); and a defensively stingy infield anchored up the middle by second baseman Gehringer and shortstop Billy Rogell.

Detroit manager-catcher Mickey Cochrane spends a few moments with Tigers owners Frank Navin (right) and his wife. Navin, who owned the Tigers since 1908, lived just long enough to see his team finally win a world title; he died shortly after his its 1935 triumph. (The Rucker Archive)

The World Series would be a distant rematch. Opposing the Tigers would be the Chicago Cubs, who handed Navin his first Series loss back in 1908.

Since their last appearance in the Fall Classic three years earlier, the Cubs had reinvented themselves by infusing youth into the roster while making trades that the local media questioned. The NL’s youngest team, the Cubs took half a season to feel themselves out; when the team chemistry gelled, they bolted. They won 20 of 23 games in July, then heated back up in September by embarking on the league’s longest win streak since the Giants’ all-time record of 26 straight in 1916.

Chicago had won 18 in a row, all at home, and led the defending champion Cardinals by three games when they hit the road for a season-ending, five-game series—at St. Louis. Dizzy and Daffy Dean, enjoying another dazzling campaign, could not work the clutch magic that brought the Cardinals from behind a year earlier. Daffy lost the first game to the Cubs, 1-0, when he allowed a solo home run to 19-year-old first baseman Phil Cavarretta; Dizzy was then knocked for a 6-2 loss the next day in the first game of a twinbill, clinching the pennant for Chicago. The Cubs’ streak ended the next day at 21—the majors’ third longest in modern times.

BTW: Outside of an 18-14 slugfest against Brooklyn, the Cubs never allowed more than three runs during their winning streak.

The Cubs were well balanced, leading the NL in hitting, runs scored, and earned run average. Right-handed starters Bill Lee and Lon Warneke each won their 20th games during the climatic series at St. Louis; 23-year-old center fielder Augie Galan led the league in steals (22) and runs (133) while 25-year-old second baseman Billy Herman, a tremendous hit-and-run artist, batted .341 with a league-high 227 hits and 57 doubles. Veteran catcher (and future Cubs manager) Gabby Hartnett won the NL’s Most Valuable Player award by hitting .341.

On the field, the Cubs focused on winning their first world championship since beating the Tigers 27 years earlier. But in the dugout, the target was Hank Greenberg, baseball’s first Jewish super-slugger. A torrent of anti-Semitic abuse flowed from the Cubs’ bench, and the animosity of the atmosphere peaked during the pivotal third game with a series of ejections and fines—mostly levied upon Cubs players.

It’s All up to You, St. Lou

With the Tigers’ 1935 championship triumph, every AL team had won a World Series at least once—except the St. Louis Browns, who were perennially happy just to reach the .500 mark. The Browns’ time wouldn’t come for another 31 years— when the franchise was known as the Baltimore Orioles.

After the teams split the first two contests, Game Three grew into a tense see-saw battle in which Detroit scored four times to take a two-run lead in the eighth inning—only to lose it in the bottom of the ninth as the Cubs sent the game into extra innings. The Tigers finally took the game in the 11th when an unearned run crossed the plate courtesy of an error by veteran infielder Fred Lindstrom—the pebble-bit, World Series goat of 11 years earlier.

That victory tilted the momentum Detroit’s way to stay—even without Greenberg, sidelined after breaking his wrist in Game Two. Holding on to take the Series in six games, the Tigers and Frank Navin could finally savor their first-ever world championship.

Not more than a month had passed after the World Series when Navin, trotting about on his horse one brisk morning, suffered a fatal heart attack. In the end, he had stuck around as planned for the satisfaction he had dreamed of.

Perhaps it was his last goal in life.

Forward to 1936: The New Yankee Juggernaut First-year star Joe DiMaggio upgrades the New York Yankees back to superpower status—and the start of an impressive dynasty.

Forward to 1936: The New Yankee Juggernaut First-year star Joe DiMaggio upgrades the New York Yankees back to superpower status—and the start of an impressive dynasty.

Back to 1934: Dizzy, Daffy and Ducky The Cardinals’ Gashouse Gang goes into full bully mode behind the dazzling Dean brothers.

Back to 1934: Dizzy, Daffy and Ducky The Cardinals’ Gashouse Gang goes into full bully mode behind the dazzling Dean brothers.

1935 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1935 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1935 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1935 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.