THE YEARLY READER

1936: The New Yankee Juggernaut

The New York Yankees return to fearsome form with Lou Gehrig in his prime—and a wave of new talent led by rookie sensation Joe DiMaggio.

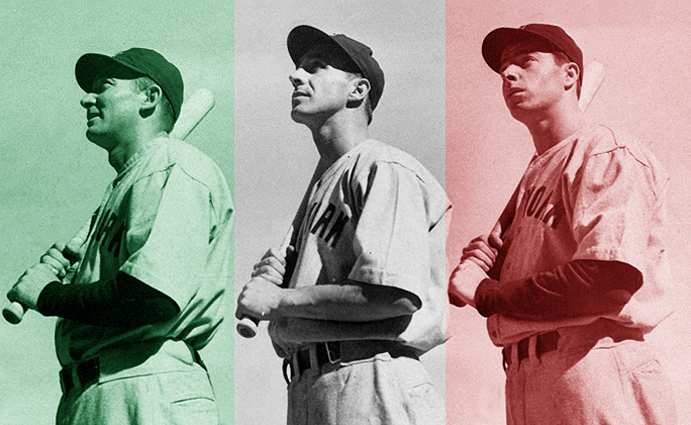

Raised in San Francisco and bathed in Italian-American heritage, Tony Lazzeri, Frankie Crosetti and star rookie Joe DiMaggio represented a more diverse and devastating cross-section of a new dynasty at Yankee Stadium. (Associated Press)

The New York Yankees experienced a rebuilding year in 1935.

They finished second.

Since Babe Ruth’s debut in New York 15 years earlier, the level of expectation dressed upon the Yankees was intense. Every new season brought demand, not hope, to win it all. Anything other than a World Series victory was unacceptable.

After a three-year absence from the Fall Classic, the Yankees would embark on a wave of newfound dominance in 1936 that would herald in, arguably, the most powerful reign of supremacy in major league history.

The Yankees had found themselves relatively handicapped in many ways the year before. Babe Ruth, his magic touch quickly fading, was released. Lou Gehrig, left behind with no other legends to protect him in the lineup, had one of his more statistically quiet campaigns. With the rest of the lineup going through an unusually active amount of renovation, the Yankees spent the year trailing a Detroit team starved and determined to win its first-ever World Series.

Worse, the marquee-talented Yankees were outdrawn for the first time in a decade by their rival across the Harlem River, the New York Giants.

Patience may very well have been the word with the 1935 Yankees, for almost everyone in the organization knew that one of the team’s best players—maybe the best—was prepping himself for the majors 3,000 miles away in San Francisco.

Joseph Paul DiMaggio fancied baseball less than his two brothers, often preferring tennis instead. But when he joined his older brother Vince with the Pacific Coast League’s San Francisco Seals and, at age 18, hit safely in 61 straight games during his first full season, it was obvious the bat held a better future than the racket.

Batting .340 with 169 runs batted in during that first year, every major league scout fell in love with DiMaggio—and the Seals knew it. Resisting all offers, the Seals kept DiMaggio in San Francisco for 1934, hoping that with more maturity he would only get better and improve his market value.

The Seals’ greed cost them. DiMaggio suffered a freak knee injury stepping out of a cab at Fisherman’s Wharf, and the disappointing season that followed gave major league execs second thoughts. In fact, there would only be one taker: The Yankees.

With competition non-existent, the Yankees named their price: $25,000, a third of what others had offered the year before, along with five minor leaguers. DiMaggio was theirs, but they’d have to wait; the deal kept him in San Francisco one more year to tune up for the majors.

The extra rehearsal probably wasn’t needed. DiMaggio hit .398 for the Seals in 1935.

Patience was out and DiMaggio was in at Yankee camp in 1936, and when he finished his first week at spring training batting .600, the buzz only grew louder. But another freak mishap forced the Yankees to be a little more patient; being treated for a foot injury, DiMaggio couldn’t escape a diathermy apparatus left on by the team doctor—who had left the room for a little too long—and it burned DiMaggio’s leg seriously enough that he would miss the first 18 games of the regular season.

BTW: The diathermy incident was eerily similar to a 1933 episode in which Boston Red Sox hitting star Dale Alexander suffered third-degree burns and nearly the loss of his leg, essentially ending his major league career.

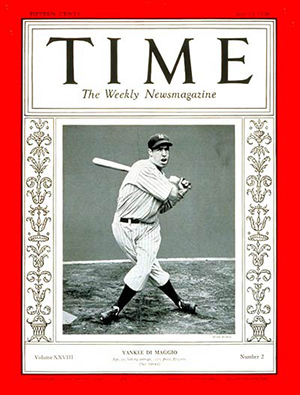

Joe DiMaggio’s rookie star was such that he made the cover of prestigious Time Magazine.

DiMaggio became the talk of the town. He was a naturally smooth customer off the field as well as on it, mixing parts grace, urbanity and cool. He made the cover of Time; he was also the leading recipient of votes for the AL All-Star team, an impressive feat considering the established presence of Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg, et al.

The instant idolization of Joe DiMaggio was not without its bumps. He went 0-for-5 and played bumbling defense at the All-Star Game. More alarmingly, he later collided with teammate Myril Hoag as the two chased a ball in the outfield, sending Hoag to the hospital with a brain clot that nearly killed him before he fully recovered.

In the end, DiMaggio’s rookie spectacle fortified the Yankees’ belief that the deal to get him was a bargain. His .323 batting average was accented with 29 homers and 125 RBIs, and only Gehrig belted more extra-base hits in the AL. In 639 at-bats, DiMaggio struck out just 39 times—the highest total of his eventual 13-year big league career.

Helped by DiMaggio’s presence, the Yankees were thrust back to superhuman strength. Protected again in the lineup, Gehrig smashed 49 home runs—14 alone against the hapless Browns, the most ever by a player against one team in a single year. Gehrig also racked up 400 total bases for the fifth time in his career—another record.

The power surge among the rest of the Yankees was electrifying. The team set a record with 995 RBIs, with five players knocking in over 100 each—including George Selkirk, Babe Ruth’s replacement in the outfield. Every regular starter in the lineup hit at least 10 home runs, except outfielder Jake Powell—and that was only because he was dealt to the Yankees at midseason. Catcher Bill Dickey set a record at his position by batting .362. Shortstop Frankie Crosetti, a traditionally poor hitter, hit a career-high .288. And first baseman Tony Lazzeri hit the lowest of all Yankee regulars at .287, but made up for his shortcomings by having the biggest day of any Yankee in 1936 with three home runs—including two grand slams—with an all-time AL record 11 RBIs during a 25-2 rout of Philadelphia in June. Further underscoring the team’s intense depth of talent, Lazzeri batted eighth in the order that day.

BTW: Jake Powell had seven home runs in his half-season at New York after collecting just one in Washington, where homers came anything but cheap at expansive Griffith Stadium.

Even New York pitchers felt the inspiration at the plate. During a June doubleheader against Cleveland, starters Red Ruffing and Monte Pearson each collected four hits; in an August start, Johnny Murphy pounded out five.

In a year where the AL exhibited its highest earned run average ever at 5.04, Yankees pitching sailed through the season with solid consistency. All five members of the New York starting rotation could be counted among the 11 AL pitchers who managed to keep their individual ERAs below 4.40.

There would be no pennant race in the AL. The Yankees made a shamble of the competition, outscoring their opponents by a whopping 434 runs and finishing nearly 20 full games ahead of reigning champion Detroit.

To rival the rejuvenated strength of the Yankees, the Tigers realized they would have to count on a lot of luck. Unfortunately for Detroit, it was rotten luck. The season was barely two weeks old when Hank Greenberg broke the same wrist he fractured during the 1935 World Series; he missed the rest of the season. Slumping along three weeks later without Greenberg, catcher-manager Mickey Cochrane suffered a series of nervous breakdowns—and at one point was exiled to Wyoming for a month-long rest—and finished the season as manager only.

While the Yankees had virtually no weaknesses to speak of, the New York Giants rambled to the National League pennant on the strength of two men—pitcher Carl Hubbell and slugger Mel Ott—and not much else.

Reversing the roles of the previous year, the Giants trailed defending NL champion Chicago by as much as 10.5 games throughout the season, then turned it on in the home stretch—winning 39 of 47 games late to overtake the Cubs.

The presence of Mel Ott and his trademark high leg-kick stance lifted the New York Giants to the top of the National League standings. (The Rucker Archive)

Offensively, Ott was even more of a one-man show for the Giants. He led the team in nearly every offensive category; his 33 home runs were followed next on the club by Hank Leiber and Jo-Jo Moore—with nine each. Leiber’s 67 RBIs were second on the Giants to Ott—who had twice as many, with 135.

Looking heavily outmanned and outgunned in the World Series, the Giants gave it the best they could behind King Carl and Master Melvin. And when Hubbell locked down the Yankees in Game One with a 6-1 victory, the aroma of a major upset hung suspended in the air.

But any illusion of a Giant October surprise quickly vanished in Game Two. The Yankees scored two in the first, seven in the third, and six more in the ninth as part of an 18-4 annihilation. Alas for the Giants, reality had set in.

The Giants could squeak out only one more victory, a 5-4, 10-inning battle in Game Five that only prolonged the inevitable; the next day, the Yankees wrapped up the Series in classic Bronx Bomber fashion, thrashing the Giants, 13-5.

Yankee bats remained as unstoppable during the World Series as they had during the regular season. Batting .302 as a team, the Yankees notched 43 runs and crashed seven home runs against the Giants. Joe DiMaggio led the charge, batting .346 with three doubles. Gehrig and Selkirk each pounded two home runs. And the Yankees eventually figured Hubbell out, scoring four early runs off him in Game Five to set the pace for a 5-2 win. It was Hubbell’s first loss in nearly three months.

Just as frustrating for the Giants was the performance of the Yankees’ pitchers—both on the mound and at the plate. Yankee hurlers combined to hit .273—decidedly higher than the .246 figure they allowed the Giants from the box.

In retrospect, congratulations were in order for the New York Giants. Though losing in six games, their performance in the World Series would be the best the National League would manage over the next four years. During this time, NL titleists would find no cracks to weaken in the impenetrable wall that would resemble, quite possibly, baseball’s best-ever dynasty: The New York Yankees of the late 1930s.

Forward to 1937: Just Push Press for Repeat The New York Yankees easily repeat as world champions behind the “push-button” piloting of manager Joe McCarthy.

Forward to 1937: Just Push Press for Repeat The New York Yankees easily repeat as world champions behind the “push-button” piloting of manager Joe McCarthy.

Back to 1935: The Babe’s Bittersweet Bow Out Babe Ruth’s final year in the majors is full of decline, frustration—and one last marvel of immortality.

Back to 1935: The Babe’s Bittersweet Bow Out Babe Ruth’s final year in the majors is full of decline, frustration—and one last marvel of immortality.

1936 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1936 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1936 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1936 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.