THE YEARLY READER

1937: Just Push Press for Repeat

Manager Joe McCarthy’s straightforward, business-like approach to guiding the New York Yankees may not be as easy as a push of a button—but don’t tell that to any of his opponents, who watch the Yankees coast to another world title.

Joe McCarthy was said to have the easiest job in baseball: Managing the talent-rich New York Yankees. But his track record and approach to the players proved that it wouldn’t be easy without him. (The Rucker Archive)

It was becoming painfully obvious to the seven other clubs of the American League: The New York Yankees were here to stay as an enduring powerhouse. All the competition could do was dig in for the long haul.

For 16 years, the Yankees dominated the AL landscape, capturing 10 pennants while occasionally hiccuping to second or third place. While many pinpointed Babe Ruth as the core to the team’s success, they also added that he couldn’t last forever; even with stars like Lou Gehrig, Lefty Gomez and company filtering the rest of the roster, the thought still went that as Ruth went, so went the Yankees.

When Ruth faded and left the Yankees after 1934, the team didn’t fold. They simply replaced one legend with another two years later in Joe DiMaggio, got back on track and won another pennant and championship in 1936. Throughout the rest of baseball, the sighs were deafening.

Rather than fall flat on their faces in post-Ruthian depression, the Yankees had further solidified their reputation as a perpetual winner loaded with marquee talent.

There were no weak points to the Yankees’ presence. They had a wealthy owner, a top-notch front office and a healthy fan base. And the Yankees’ dynastical character became great advertising for their thriving farm system, as the scouts became the scouted; there were few prospects across the land that didn’t salivate at the wistful thought of donning pinstripes and becoming the next Yankee legend in line after Ruth, Gehrig and now DiMaggio.

While owner Jacob Ruppert and general manager Ed Barrow ran the production upstairs, the show on the field was directed by Joe McCarthy, beginning his seventh year as Yankees manager in 1937. McCarthy had perfected his role within the team; a cool disciplinarian, he was not Napoleonistic like John McGraw, nor did he seek the limelight other managers hunted for to stand out above their players. He simply knew his job, knew how to use his players, and stood contently and quietly in the shadows like an operator watching over a well-oiled machine, making sure it ran smoothly from day to day.

Chicago manager Jimmy Dykes, for one, knew what he was up against when playing the Yankees. The overseer of an improving White Sox club, Dykes acknowledged he was no match for the machine-like precision of the Yankees—and would coin a memorable title when he referred to McCarthy as a “push-button manager.”

McCarthy despised the term, thinking he was not being given the proper respect for his managerial talents. But he couldn’t deny the ease of running the 1937 Yankee engine; if one part failed, he found another just as good to replace it.

This was especially true of McCarthy’s outfield. Jake Powell and George Selkirk, starters from the year before, were hounded by injuries; benchwarmer Myril Hoag filled one spot with a .301 average, while 24-year-old Tommy Henrich—who jumped at the chance to sign with the Yankees for $25,000 after commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis freed him from the Cleveland farm system—filled the other, batting .320 in 67 games to begin a lucrative career at New York.

Otherwise, there was little McCarthy needed to do except let the Yankee machine do its thing.

The strength of that machinery lay in McCarthy’s two-man wrecking crew of Gehrig and DiMaggio. There was no breaking down in these main motors; Gehrig batted .351 with 37 home runs and 159 runs batted in, and DiMaggio—thoroughly enjoying his sophomore year in New York—hit .346 with career highs in homers (46) and RBIs (167). At one point, DiMaggio was on pace to overrun Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record of 60, but the right-handed slugger was eventually defeated by Death Valley, Yankee Stadium’s seemingly endless distance to left-center field which had been reduced for the 1937 season. DiMaggio later claimed that he might have hit 70 had the reach to the fence been more average.

While the Yankees as a team did not lead the AL in batting, they still knew how to rack up the runs—thanks to league-high marks in slugging percentage and home runs. Just as importantly, their pitching remained top-flight, anchored by 20-game winners Lefty Gomez and Red Ruffing. The staff’s 3.65 earned run average led the AL by a wide margin, and Gomez’s 21 wins, 194 strikeouts and 2.33 ERA each won individual league honors.

Multiple Trifectas From the Mound

As strikeouts go, Lefty Gomez didn’t strike fear into opponents as others on the list below, but he still managed to join the elite group of pitchers who (at least) twice won the pitchers’ triple crown—ranking first in wins, earned run average and strikeouts.

For the second straight year, the Yankees’ lead in the AL was double-digit by year’s end. It was runner-up status again for the Detroit Tigers, and a second straight year of pain for manager Mickey Cochrane. A year after being ordered to the bench following a mental breakdown, Cochrane felt ready to return to action in 1937—and would later regret it.

In a May 25 game against the Yankees, a Bump Hadley fastball nailed Cochrane square on the forehead, knocking him instantly into a coma with a triple-fracture to his skull. Seventeen years after former Yankees pitcher Carl Mays beaned Ray Chapman to death, horrified Yankee Stadium onlookers feared Cochrane had become big league baseball’s second on-field fatality; he remained comatose and in critical condition for a week before awakening, spending another six weeks recuperating to a full recovery. Doctors gave Cochrane the last word when they discharged him: Manage from the dugout if you’d like, but no more playing. Cochrane took the suggestion to heart, ending a 13-year career in which he batted .320.

BTW: Cochrane would remain in the spotlight through the 1940s, actively promoting baseball’s contributions to America during World War II, and would later be enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

With or without Cochrane, the Tigers had an overpowering offense to match the Yankees. Hank Greenberg knocked in 183 runs, one short of Lou Gehrig’s all-time AL record; Charlie Gehringer led the AL in hitting at .371; and muscular rookie Rudy York made a thunderous splash by smashing 35 home runs with 103 RBIs—in only 104 games. But the pitching collapsed. Schoolboy Rowe, with 62 wins to his credit over the previous three years, had arm trouble in 1937 and made all of two starts. Roxie Lawson led the team with 18 wins, but with a poor 5.27 ERA attached. Overall, the Tigers’ ERA was next-to-last in the AL, and Detroit finished 13 games back of New York.

A Glut of Prime Ribbies

Hank Greenberg’s 183 RBIs in 1937 brought him just one short of the AL record, and eight shy of Hack Wilson’s all-time mark. As the list below shows, eight of the top 10 all-time RBI performances came during the 1930s—and eight of them were American Leaguers.

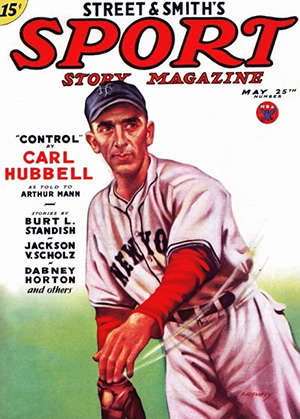

While the Yankees breezed, the New York Giants sweated out another close National League race, again with little more to vouch for on their roster outside of pitcher Carl Hubbell and slugger Mel Ott—both of whom had double-handedly brought the team to a pennant the year before.

Hubbell picked up where he left off in 1936, winning his first eight decisions to extend his consecutive-win streak to 24—a major league record that still stands. NL President Ford Frick, who would become something of a scrooge when it came to the record books, said that such a mark could be established for wins over one season only, meaning Hubbell’s streak should have stopped at the end of 1936 with 16.

BTW: Frick also forged himself into the center of controversy in 1961 when, as baseball’s commissioner, he ruled that Roger Maris’ home run season record was legitimate only if he accomplished the feat in 154 games or less.

For a change, Hubbell was not a one-man show on the Giants’ staff, as 25-year-old rookie southpaw Cliff Melton won 20, saved seven— and bested Hubbell on the ERA charts with a 2.61 figure.

New York Giants ace Carl Hubbell ran his streak of consecutive wins (started in 1936) to a record 24, on his way to winning at least 20 games for the fifth straight season.

For the second straight year, the Chicago Cubs couldn’t hold up under the strain of first place—blowing a 6.5-game lead in mid-August to bow to the Giants. The principal culprit at Wrigley Field was the Cubs’ pitching staff, which lacked the Giants’ muscle on the mound. Chicago finished three games back.

At fourth-place St. Louis, it was the downfall of the Brothers Dean. Daffy the Silent developed arm trouble the year before and was basically finished as a pitcher by 1937. Dizzy, meanwhile, continued as strong—and pugnacious—as ever. Facing the Giants in May, Dizzy was charged with a balk—nullifying a fly out and igniting a three-run, sixth-inning New York rally that would ultimately lead them to victory. Incensed, Dizzy took his anger out by brushing back (if not worse) every Giants hitter he faced over the final three innings, and finally exploded when he broadsided Jimmy Ripple, running down the first base line on a bunt—igniting a nasty, all-out brawl between the two teams after the final out. Ford Frick leveled a fine on Dizzy, who retaliated by calling Frick a crook—which got him into real trouble. A suspension ensued, which only antagonized Dizzy more; he threatened to boycott the All-Star Game he’d been selected to.

BTW: In his only appearance of 1937, Daffy Dean faced three hitters, allowing one hit while walking the other two; all three scored. Dean’s ERA for the season: Infinity.

Dizzy probably wished he had carried out his threat. Starting the first three innings of the Mid-Summer Classic, Dizzy’s last out became a costly one; Earl Averill lined a shot that ricocheted off Dean’s foot, causing a fracture of the toe. Defiantly trying to shorten his stay on the disabled list, Dizzy altered his pitching delivery so it put less stress on his toe; it instead put a huge strain on his pitching arm, which became permanently damaged. Though he would pitch into the 1940s, Dizzy Dean would be a crippled shadow of his former self, pitching infrequently and in excruciating pain on the mound.

Entering the World Series, the Giants felt more evenly matched against the Yankees, but when they lost their first two games by identical 8-1 scores at Yankee Stadium, they got that old sinking feeling—which segued to freefall after the third game, won by the Yankees, 5-1.

Facing the insurmountable task of having to win four straight over the Bronx Bombers, the Giants at least staved off a sweep by winning Game Four behind Hubbell, 7-3. But Yankee ace Lefty Gomez finished off the Giants in Game Five with a 4-2 triumph.

While the Yankees’ bats cooled during the Series—they hit only .249 as a team—there were plenty of contributions otherwise. The pitching staff limited the Giants to a .237 average and just seven extra base hits—including only one home run, by Mel Ott—for a stellar 2.45 ERA. Defensively, the Yankees became the first team in Series annals to not make a single error; the Giants committed nine.

Victorious again, the Yankees’ back-to-back championships equaled the triumphs of the 1927-28 editions. From St. Louis to Boston and all major league points in between, deflated owners shook their heads and sighed in disbelief. The National League now got the same message long since delivered throughout the American League: The New York Yankees were a genuine superpower. If something needed replacing, Joe McCarthy was there to push the button. If an icon had slipped into mediocrity, there was surely another one waiting in the wings.

Life was indeed sweet for the Yankees.

But a little adversity was on the way.

Forward to 1938: A Rockier Road The New York Yankees’ quest for a third straight world title is roughened with controversy.

Forward to 1938: A Rockier Road The New York Yankees’ quest for a third straight world title is roughened with controversy.

Back to 1936: The New Yankee Juggernaut First-year star Joe DiMaggio upgrades the New York Yankees back to superpower status—and the start of an impressive dynasty.

Back to 1936: The New Yankee Juggernaut First-year star Joe DiMaggio upgrades the New York Yankees back to superpower status—and the start of an impressive dynasty.

1937 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1937 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1937 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1937 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.