THE YEARLY READER

1941: 56, .406 and Dem Bums

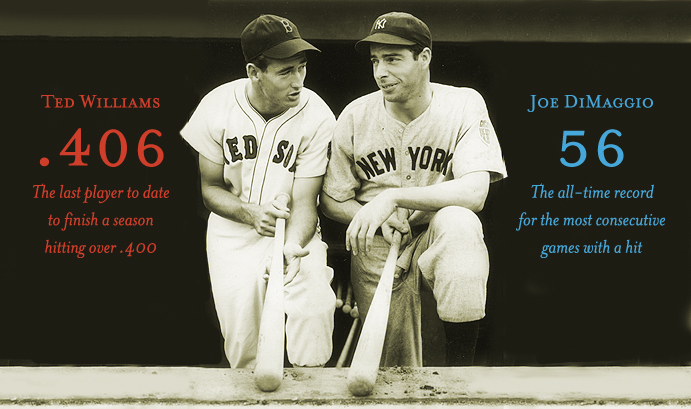

One of baseball’s most memorable seasons witnesses Joe DiMaggio’s wildly popular 56-game hitting streak, Ted Williams’ quest to bat .400 and the stirring rise of the Brooklyn Dodgers as they capture their first NL pennant in 21 years—and their first of many to come.

Throughout a 100-year period as rich in sports history as the 20th Century, it’s hard to top the energy and magnificence of Major League Baseball in 1941.

Snapping out of a decade of depression, the game’s marquee grew bright with one of its most glorious campaigns ever. Headlining the show would be a pair of celebrated milestones from two of baseball’s hottest household names. It would also witness a strengthened franchise embarking on a fabled era that would become, arguably, the most nostalgic in the game’s history.

The 1941 season also signaled the return of the New York Yankees to the top of the American League—though it wasn’t entirely apparent in the first four weeks of the season.

After being hammered 13-1 by the Chicago White Sox on May 15, the Yankees dropped their record to 14-15—not exactly the big comeback the Bronx Bombers were looking for, especially on the tail of a disappointing 1940 campaign in which they were ridiculed as a band of aging former All-Stars. Yet little did anyone realize during the White Sox’ rout that a standard single by Joe DiMaggio would ignite one of the sport’s most legendary achievements and rejuvenate the Yankees back to life.

At 26 years of age, the Yankee Clipper began to continually collect at least one hit from each game to the next. Before anyone knew it, DiMaggio’s hitting streak had reached 20 games, and the local newspapers promoted the growing story from the buried trivial notes section to the headlines. When DiMaggio broke the Yankees team record of 29 straight games, the national press sat up and took notice.

As the streak sailed into the 30s, Wee Willie Keeler’s all-time record 44-game hitting string from 1897 grew larger on the horizon. Those involved in the making of the box scores became increasingly conscious of their possible roles in advancing—or breaking—DiMaggio’s run at the mark.

In games 30 and 31 of his streak, DiMaggio managed just one single in each—tough grounders hit at White Sox shortstop Luke Appling, who had trouble making the play and, had his glove game been perfect, might had gotten DiMaggio out. Such judgment calls caused nightmares for official scorers; the one hired by the Yankees had his phone number changed out of fear that charging an error on a close play might deprive DiMaggio of a hit and the continuation of his streak—and deprive the scorer of the continuation of his life from some maniac who didn’t like his call.

Opposing pitchers felt the pressure as well. With the streak sitting at 37, a hitless DiMaggio faced St. Louis Browns pitcher Elden Auker in the eighth inning with a runner on second—and first base open in a tight ballgame. Normally inclined to give a batter—especially the dangerous DiMaggio—an intentional walk to set up a force play in that situation, Auker knew that this default strategy would likely end the streak and cast him as a historical spoilsport for eons to come. He decided to challenge DiMaggio and give history a chance. DiMaggio doubled.

Joe DiMaggio hits away against Cleveland’s Al Milnar in the game he would stretch his legendary hitting streak to 56 games. A day later, he would go hitless in three at-bats with a walk. (The Rucker Archive)

Press coverage of DiMaggio’s streak quickly reached a level of obsession. Never mind that world-wide war was closing in on America; from coast to coast, the question became, “How did Joe do today?”

In short order, the records fell. In the first game of a Yankee Stadium doubleheader against Washington on June 29, DiMaggio doubled to tie George Sisler’s AL mark of 41 straight games; in the nightcap, he broke it with a single. With quieter fanfare, he surpassed the all-time mark for a right-handed hitter, set by Bill Dahlen in 1894, in the first game of a twinbill two days later against the Boston Red Sox. In the second game that day, DiMaggio lashed a single off the Red Sox’ Jack Wilson—and tied Keeler’s record.

The mark fell the next day in style; DiMaggio launched a three-run homer off Boston pitcher Dick Newsome to boost the Yankees to an 8-4 win. The ecstatic Yankee Stadium crowd of 52,000 included an eager young fan from New Jersey who reached in during a rain delay and swiped the bat used by DiMaggio throughout the streak. It was returned a few days later.

The burden of breaking the record now behind him, DiMaggio relaxed and powered his streak to uncharted heights—batting .545 over the next 11 games, extending the string to 56 before watching it end on July 17 at Cleveland. A terrific display of glovework by the Indians infield, including two difficult plays by third baseman Ken Keltner, kept DiMaggio hitless for the first time in two months.

As if riding on momentum, DiMaggio started a new hitting streak of 16 games the next day—giving him an incredible stretch of 73 games in which he hit safely in 72.

BTW: DiMaggio fell short of just one streak—his own, a 61-game run he fashioned while playing in the minors at San Francisco in 1933.

Jolted by Joe

As Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak would dictate, consistency ruled as none of the teams the Yankee Clipper played against was spared.

Throughout his legendary 56-game journey, DiMaggio batted .408 with 15 home runs, knocked in 55 runs and scored 56 more. He struck out just seven times. His actions also sparked the Yankees as a team; New York won 41 while losing just 13 (with two discounted ties) during the streak. While everyone focused on the record, the Yankees quietly resurfaced to full strength and accelerated from there, clinching the pennant almost four weeks before season’s end.

BTW: While DiMaggio was hot, the Yankees as a team were producing another record-setting streak: The most consecutive games with a home run, at 25 (since broken).

The lack of serious competition also aided the Yankees’ cause. Reigning AL champion Detroit blew a few tires and lapsed below the .500 mark. The Tigers were hindered by the absence of Hank Greenberg, drafted into military service after just 19 games; slugger Rudy York, slumping to a more ordinary presence; the collapse of Charlie Gehringer, the automatic .300 man who sank to .220; and pitcher Bobo Newsom, who, a year after winning over 20 games, lost 20.

With the DiMaggio streak—and the AL pennant race—over, the main focus turned toward a cocky 22-year-old outfielder at Boston who had no hitting streak going—but masterfully was keeping his batting average at or above .400 all year long.

In just his third major league season, Ted Williams had long since proven his value as a superstar of the highest order. He batted .327 and .344 with power to match in his first two years with the Boston Red Sox, but in 1941 he really cut loose. By June he was hitting close to .440, even after an ankle injury slowed him up at the start of the year. He cooled off and quietly straddled the .400 mark throughout the summer while all the media noise was concentrating on DiMaggio’s streak—an overshadowing that sat quite well with Williams, who didn’t crave the intensive focus from reporters for whom he had developed a tense relationship with.

The Making of a .400 Season

The word “slump” was absent from the 1941 vocabulary of Ted Williams, whose batting average wavered but never strayed too far south of his legendary, final .406 mark.

On the next-to-last day of the regular season, Williams went 1-for-4 against the Philadelphia A’s and, for the first time since mid-July, fell below .400. Well, sort of. His average was actually at .39955—which, in statistical baseball language, officially rounded out to .400. The final day offered up a doubleheader against the A’s, and Red Sox manager Joe Cronin offered Williams to take both games off and sit on the number. Williams thought about it, walking the streets of Philadelphia the night before deciding that he was far too proud to let the decimal system earn him the average; he wanted to go bat and earn a “true” .400 for himself. He quickly killed the suspense by going 4-for-5 in the first game, then grabbed two more hits in the nightcap to raise his final mark to .406.

Seven players previous to Ted Williams had hit .400 in the 20th Century, but no one had done it since Bill Terry 11 years earlier, while Harry Heilmann had been the last American Leaguer to do it—in 1923.

And no one has done it since.

BTW: Under today’s scoring rules, Williams’ average would be .411; six sacrifice flies Williams hit to the outfield were counted as at-bats in 1941.

Not to be outdone by the AL’s individual achievements, the National League gave baseball its first taste of the Boys of Summer. The Brooklyn Dodgers had become chic.

For years one of the premier laughingstocks of baseball, the Dodgers wandered under the clown-like leadership of Wilbert Robinson and, briefly, Casey Stengel. They were infamous for making outlandish bonehead plays, including the historic moment when Babe Herman attempted to stretch a double into a triple—only to find two other Dodgers standing alongside him at third base.

A serious attitude adjustment was bound to occur when Larry MacPhail came to Brooklyn as its new general manager in 1938. Having rescued the Cincinnati Reds from financial ruin in the mid-1930s, he took over a Dodgers club which itself was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. MacPhail immediately made it clear that the zany days of lore would no longer be tolerated; he upgraded Ebbets Field, installed lights and shattered a gentleman’s agreement between the three New York City ballclubs by putting Dodgers games on radio.

MacPhail also hired as his manager Leo Durocher, who like previous Brooklyn skippers showed a theatrical presence on the field—but also held a far more competitive urge to win.

BTW: MacPhail opted for Durocher as Babe Ruth, coaching for the Dodgers under previous manager Burleigh Grimes, thought he’d get the call.

Two fiery personalities with short fuses, MacPhail and Durocher got along like spontaneous combustion. It’s been said that MacPhail fired Durocher as much as 100 times during their tenure together—only to have MacPhail always take it back the next morning. They loathed each other, yet respected one another enough to co-exist.

Together, MacPhail and Durocher built up a quick and impressive winner at Brooklyn. A series of shrewd trades and acquisitions had turned the Dodgers from a second-division mainstay into pennant favorites within three short years. By 1941, all eight Brooklyn field regulars and starting five pitchers began their professional careers with other major league organizations.

The Dodgers were every bit as good as their 100 victories attested. As a team they led the NL in most major statistical categories, and individually there were standouts everywhere. Dolph Camilli led the league with 34 home runs and 120 RBIs; Pete Reiser matched Ted Williams in age (22) and in winning a batting title—albeit well below .400 (at .343); and rough-and-tumble pitching types Kirby Higbe and Whit Wyatt both shared the league lead with 22 victories apiece.

A team-record 1.2 million fans came to Ebbets Field to watch the Dodgers, and they were about as much an attraction as the team on the field. Leading the way was superfan Hilda Chester, a large physical presence with a booming voice and cowbells to match. Equally noisy was the Dodger “Sym-Phony,” a celebrated rag-tag band who made their debut at Ebbets in 1941.

Still, Brooklyn and its fans had to sweat out a fairly tight NL race. Durocher’s former employers, the St. Louis Cardinals, gave the Dodgers all they could handle before finally tiring out at year’s end, finishing 2.5 games back.

The one that got away: Mickey Owen’s passed ball on what would have been a game-winning strikeout for Brooklyn puts the Yankees’ Tommy Henrich on base; the next four batters reach and the Yankees win to take control of the World Series over the Dodgers. (The Rucker Archive)

In a highly anticipated World Series match-up between the Yankees and Dodgers—the first of seven that would pair the two over the next 15 years—the teams traded 3-2 victories to begin the Series. After another close Yankee triumph in Game Three, the Dodgers were but a pitch away from evening things up in Game Four.

Brooklyn led 4-3 in the ninth inning with two outs and no one on, and Dodgers pitcher Hugh Casey had the Yankees’ Tommy Henrich down to his last strike. Carey’s next delivery was a sharp curve ball—some believe it was a spitter—that Henrich couldn’t make contact with; unfortunately for the Dodgers, neither could catcher Mickey Owen, and the ball rolled back to the backstop. Since a putout had to be made on a strikeout, the ball was still alive. Henrich reached first base before Owen could collect the ball; the out did not count.

BTW: Casey on the strikeout that wasn’t: “I’ve lost games in a lot of ways, but never by striking out a batter.”

The Yankees stayed alive, then thrived, on a harried Casey. The next four batters all reached safely, climaxed by a two-run double by Joe Gordon that ultimately gave New York a 7-4 win. The heartbreaking loss was the knockout blow to the Dodgers, who never recovered and lost the Series in five games.

The grand events of 1941 seemed to return the swagger that big league baseball had been missing since the 1920s. The depression had come and gone, new idols had arrived on the scene, and fan enthusiasm had reached a new high.

But the game’s revived energy would indefinitely be quelled two months later at Pearl Harbor.

Forward to 1942: The Home Grown Champions The St. Louis Cardinals benefit from their vast farm system to become the baseball’s first wartime champion.

Forward to 1942: The Home Grown Champions The St. Louis Cardinals benefit from their vast farm system to become the baseball’s first wartime champion.

Back to 1940: Victorious Healings The Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers, two teams coping with personal loss, dedicate themselves toward winning a World Series title.

Back to 1940: Victorious Healings The Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers, two teams coping with personal loss, dedicate themselves toward winning a World Series title.

1941 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1941 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1941 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1941 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Former major leaguer Dario Lodigiani discusses his friendship with Joe DiMaggio and on getting to know his wife—one Marilyn Monroe.

Former major leaguer Dario Lodigiani discusses his friendship with Joe DiMaggio and on getting to know his wife—one Marilyn Monroe.