THE YEARLY READER

1973: Take My Division, Please

In one of the closest—and mediocre—pennant races in history, the New York Mets emerge on top of the NL East with an ordinary 82-79 record, then show extraordinary gains in the postseason against powerhouse opponents Cincinnati and Oakland.

In his final year as a ballplayer, Willie Mays pleads with umpire Augie Donatelli after a disputed call works against the New York Mets in the World Series. Before catching fire at season’s end, Mays’ Mets—and five other second-rate NL East teams—were pleading with skeptics just to be taken seriously. (Associated Press)

Sooner or later, it was bound to happen.

After the National and American Leagues each split their ranks into two six-team divisions in 1969, there was a fear that the team who played best over 162 games wouldn’t necessarily win the pennant, beaten instead by a “backdoor champion”—an inferior opponent from an inferior division, a team that could get lucky and catch fire when it mattered the most, at playoff time. A team that, in the old pre-divisional format, would have barely registered in the pennant race.

In 1973, the National League’s Eastern Division would serve up a backdoor champion that practically had to be pushed through the door. It was a comical campaign in which six mediocre teams treated first place like a live hand grenade, frantically tossing it around to one another as if to say, “Here, you take it!”

When the New York Mets were left holding the grenade to finish the regular season, they didn’t go ka-boom in the postseason as expected. Instead, they dug in and took on powerhouses in the Cincinnati Reds and Oakland A’s—and went the distance in an attempt to forge one of baseball’s greatest upsets.

After shocking the world with their miracle performance of 1969, the Mets regressed back into baseball’s middle class, struggling to stay above the .500 mark for three years. They were especially challenged in 1972 with the death of highly respected manager Gil Hodges and a horrible trade that gave them a depreciated Jim Fregosi at the cost of four Mets—including Nolan Ryan. Even with the reliable Yogi Berra settling in as Hodges’ replacement, none of the preseason pundits thought highly of the Mets for 1973.

Then again, no one thought highly of anyone in the NL East. And for good reason.

The Pittsburgh Pirates, beset by the tragic offseason death of Roberto Clemente, were considered handicapped in their quest for a fourth straight NL East title. The St. Louis Cardinals were confident they could rekindle their glory days of the 1960s, though their roster was a collection of aging veterans and young prospects—with little in between. Same for the Chicago Cubs, an even older squad trying to carry over the momentum from a strong finish in 1972. The Philadelphia Phillies were hoping to rally the youthful bulk of their roster—including two promising young sluggers in Mike Schmidt and Greg Luzinski—to improve on a disastrous 1972 season. And there was even some buzzing in Montreal, where the Expos were slowly starting to grow out of their expansion infancy.

As the 1973 season progressed, it was possible that a winning record wouldn’t be required to take first place in the “NL Least,” as some people sarcastically began to label it.

The Pirates sped out of the gate but quickly conceded their lead to the Cubs, who for the first half of the season actually looked like a genuine power, threatening to make the divisional race a non-issue by July. But by midsummer, Chicago suffered a startling collapse—losing 33 of 42 games to drop like a rock in the standings and ignite a wide-open race for the top. This paved the way for St. Louis, stunningly climbing its way to the top spot after a horrendous 5-20 start. And just when the Cardinals appeared ready to run away with the division, the injury bug hit them in the worst way, as a season-ending knee injury befell 37-year-old pitching ace and team spiritual leader Bob Gibson.

The Ups and Downs of the NL East

Like musical chairs, each of the six NL East teams experienced serious brushes with both first and last place during the 1973 season.

By the end of August, fans couldn’t believe what they were seeing in the paper: A mere six games separating first place from last in the NL East. Holding up the rear, as they had for most of the summer: The Mets.

Throughout the summer, the Mets had been grounded in the standings, devastated by injuries and flogged by the local press. The New York Post, never one for subtlety, shouted out a poll asking readers who in the Mets’ front office—beloved manager Yogi Berra included—should be fired. If anyone was to win this NL East race, any mention of the Mets would elicit a sarcastic chuckle.

At their nadir, the Mets were given a bland clubhouse pep talk from Chairman of the Board Donald Grant, stressing the word “believe” in an attempt to rouse the troops. It didn’t seem to be working. Worse, to Grant and the players, spunky reliever Tug McGraw suddenly sprang to life and carried on the speech with heavy emphasis on the phrase “You gotta bee-lieve!” Horrified teammates initially thought McGraw was making fun of Grant right in front of his face, but slowly they realized that he was seriously imbued by Grant’s sermon.

Perceived mockery became a rally cry. The Mets became healthy for the stretch and began to win—and believe.

Before anyone knew it, the Mets had hurdled the short distance from last to second, separated from first place only by the Pirates—who had regained the lead after the early September return of manager Danny Murtaugh (his fourth tour of duty in 16 years as Pittsburgh skipper) and despite a pitching staff that had fallen apart. In late September, during a string of five straight games against the Pirates—two at Pittsburgh, three at New York—the Mets would save their best for last, winning four of the five and launching them on a seven-game win streak that carried them into first place.

BTW: The most notable collapse among Pirates pitchers was starter Steve Blass, who after winning 19 games in 1972 suddenly couldn’t find the strike zone—finishing 3-9 with a 9.81 ERA.

The season’s final weekend underscored the wildness of the NL East; one scenario in which five teams finished tied for first was still possible. But the Mets had control of their destiny and took advantage of it, winning two out of three at Chicago to finish the season 1.5 games up on second place St. Louis, 2.5 over Pittsburgh, 3.5 over Montreal and five over Chicago. New York won 24 of its final 33 games after being in last place on August 30.

Excellent New York pitching helped atone for a lineup of hitters that couldn’t hit, score or run. Only the San Diego Padres, losers of 102 contests, kept the Mets from finishing dead last in almost every major NL offensive category. Tom Seaver took the NL Cy Young Award with a 19-10 record and league-best 2.08 earned run average. Tug McGraw, the team’s unofficial cheerleader, led by example from the bullpen, collecting five wins, 12 saves and a 0.88 ERA over his last 19 appearances.

Sporting the worst record to date by a postseason participant, the 82-79 Mets entered the NLCS looking like defenseless gladiators in an arena full of lions—a part to be played by the Cincinnati Reds.

In a positively more dominant NL West, the powerful Reds matched the Mets in come-from-behind heroics by overcoming a 7.5-game deficit to surpass the Los Angeles Dodgers—a team finally learning how to hit at Dodger Stadium. Any similarities to the Mets ended there; with a potent lineup of All-Star hitters (Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench and Dave Concepcion), a solid, underrated pitching staff and 99 wins—eight of them against the Mets, in 12 tries—the Reds were all but considered a pass to move onto their second straight World Series.

Strong New York pitching helped achieve a two-game split at Cincinnati to open the NLCS, leading one of the Mets’ popgun hitters—veteran shortstop Bud Harrelson—to pop off afterward to the press, comparing the Reds’ hitting to that of his emaciated own. Intended as a backhanded self-putdown, Harrelson’s comments nevertheless enraged the Reds, who were itching to respond back.

Their messenger would be Pete Rose.

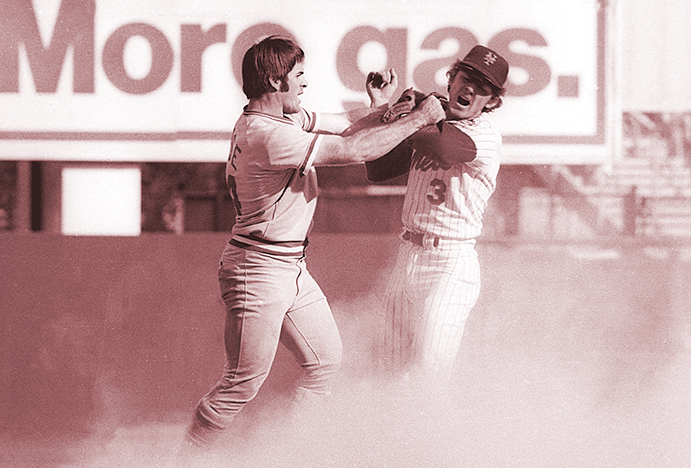

Ticked off after the Mets’ Bud Harrelson dared to compare his subpar offensive skills to those of the high-powered Reds, Pete Rose gets even by scuffling with Harrelson at second base in NLCS Game Three. The fight failed to spark the Reds, who lost in a stunning upset to New York in five games. (Associated Press)

In Game Three at Shea Stadium, the Mets’ offense had an epiphany and erupted for a 9-2 lead after four innings. But Rose, ever the competitor, tried to set a spark in the fifth. Taking a base after being hit by a pitch, Rose attempted to steal second—where Harrelson was waiting. A rough slide became coarse words, which became wild fisticuffs. Incredibly, Rose wasn’t ejected—but after instantly becoming Gotham’s Most Wanted for going after the beloved Harrelson, he probably wished he had been. Typically fanatical Mets fans nearly caused a forfeit when they made Rose, returning to the outfield on defense, a target of anything they could throw; they only stopped after a delegation of star New York players, including Tom Seaver and Willie Mays, ran out and pled with them to cool it.

Rose’s payback seemed to wake only himself up, not his teammates. He single-handedly kept the NLCS alive in Game Four with a 5-for-5 performance, including a game-winning homer in the 12th inning. But behind Seaver in Game Five, the Mets put the exclamation point on a major upset with a 7-2 win to advance to the World Series.

BTW: For the NLCS, Rose batted .381; the rest of the Reds collectively hit .158.).

Having slain one Goliath, the Mets now had to ready themselves for another in the defending world champion Oakland A’s.

The A’s looked no less a formidable opponent than Cincinnati. Charles Finley’s wild bunch was more rounded, cohesive and altogether improved over the 1972 edition. Reggie Jackson led the American League in homers (32) and runs batted in (117). Sal Bando (29 home runs, 98 RBIs) wasn’t far behind. Gene Tenace (24 home runs, 84 RBIs, 101 walks) proved that his spectacular World Series performance of a year earlier was no fluke. Billy North gave the team a leadoff presence with a .285 average, 53 steals and a league-high 99 runs. Three pitchers—Catfish Hunter, Ken Holtzman and a revitalized Vida Blue—each won at least 20 games. Rollie Fingers authored a 1.91 ERA with 22 saves from the bullpen.

In getting to their second straight World Series, the A’s relied heavily on two strong starts from Hunter—the second being a five-hit shutout—in the ALCS to overcome a Baltimore Orioles squad rejuvenated with youthful speed after sputtering the year before.

BTW: Having finally clipped the million mark in attendance during the regular season, the A’s could only draw crowds of 27,000 and 24,000—barely half capacity at the Oakland Coliseum—for the final two games of the ALCS.

The first two games of a lively World Series at Oakland proved two things: That the New York Mets were still out to prove they were no pushovers, and that Charles Finley was still stealing the headlines.

After losing a 2-1 squeaker in Game One, the Mets watched as the A’s become their own worst enemy in Game Two—committing five errors, the two most crucial of which were charged to backup second baseman Mike Andrews that put four 12th-inning runs across the plate in a wild 10-7 New York victory.

Finley was so irate over the performance of Andrews—an All Star-turned-journeyman whose defensive skills had horribly eroded—that he blackmailed Andrews into signing an agreement to sit out the rest of the Series due to a “shoulder ailment.” This raised the hackles of Andrews’ teammates, who wore black armbands in his support before Game Three and considered boycotting the rest of the Series until Andrews was reinstated; of manager Dick Williams, who decided he’d had enough of Finley and would resign from the A’s, win or lose, following the Series; and commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who overrode Finley—one of his biggest adversaries—and ordered Andrews back on the roster.

BTW: Andrews claimed Finley would “destroy” his career if he didn’t sign the document to sit out the rest of the World Series.

Trying to stay focused on baseball, the A’s struggled in the next three games at New York, squeezing out only an 11-inning, 3-2 win in Game Three. The Mets, once again buoyed with strong pitching, headed back to Oakland needing just one win in two tries to secure a Series triumph that would have been far more amazing than their out-of-nowhere 1969 accomplishment.

But the power of the A’s—more notably, the power of Reggie Jackson—finally put an end to the Mets’ improbable journey. Playing under a credible death threat that required FBI protection, Jackson collected a pair of run-scoring doubles in Game Six to back Hunter, who outdueled Seaver 3-1. And in Game Seven, Jackson smacked a two-run homer to cap a four-run, third-inning outburst to oust starter Jon Matlack and, eventually, the Mets, 5-2.

BTW: For the second straight World Series, the A’s won in seven despite being out-hit and outscored.

From last place on the eve of September to the seventh game of the World Series, the Mets’ exciting ride into October was criticized by those who felt that an average ballclub had unfairly seized serendipity and exposed the warts of baseball’s brave new world: A world full of divisional play and multiple postseason rounds where great teams could get lost and lesser teams could be discovered, for all they were worth. The argument was valid; by the record, eight major league teams were better than the 1973 Mets.

But in the minds of many, the Mets—all 88 wins and 85 losses’ worth of them—nearly got to claim number one.

Forward to 1974: “I’m Just Glad It’s Over” Hank Aaron’s long and personally painful ride to home run history comes to a successful conclusion.

Forward to 1974: “I’m Just Glad It’s Over” Hank Aaron’s long and personally painful ride to home run history comes to a successful conclusion.

Back to 1972: Labor Pains Major league ballplayers go on strike for the first time, leaving behind a bitter taste for angry fans.

Back to 1972: Labor Pains Major league ballplayers go on strike for the first time, leaving behind a bitter taste for angry fans.

1973 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1973 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1973 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1973 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.